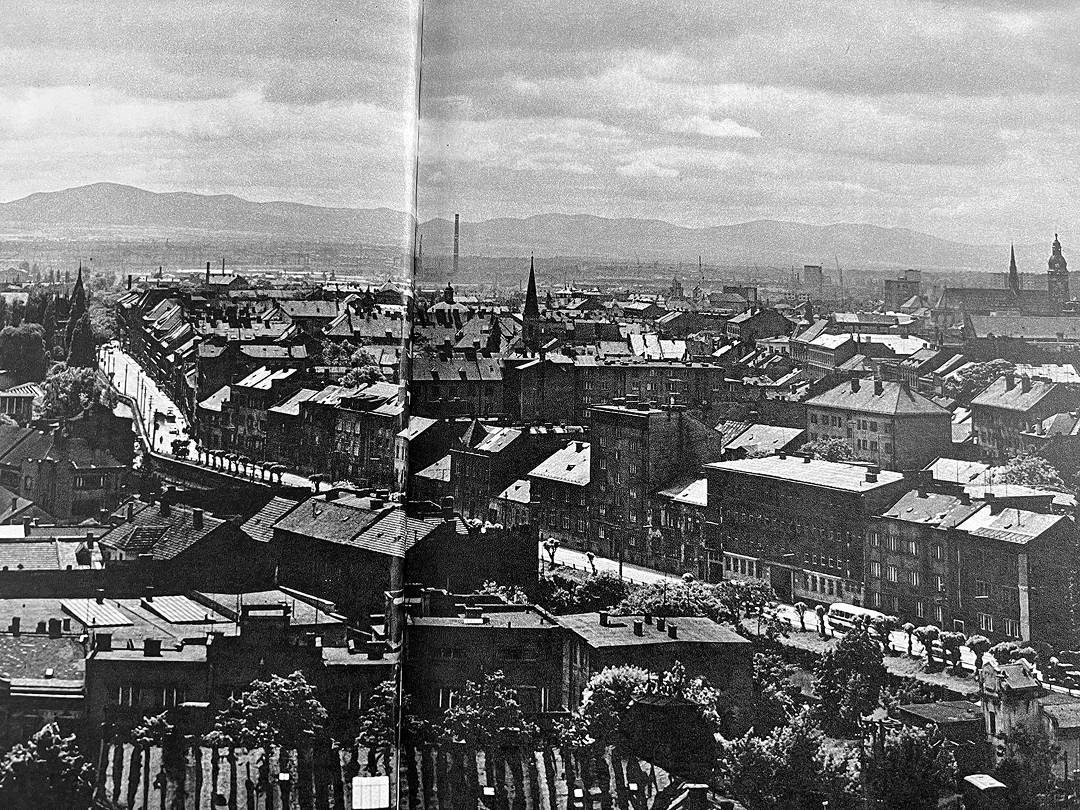

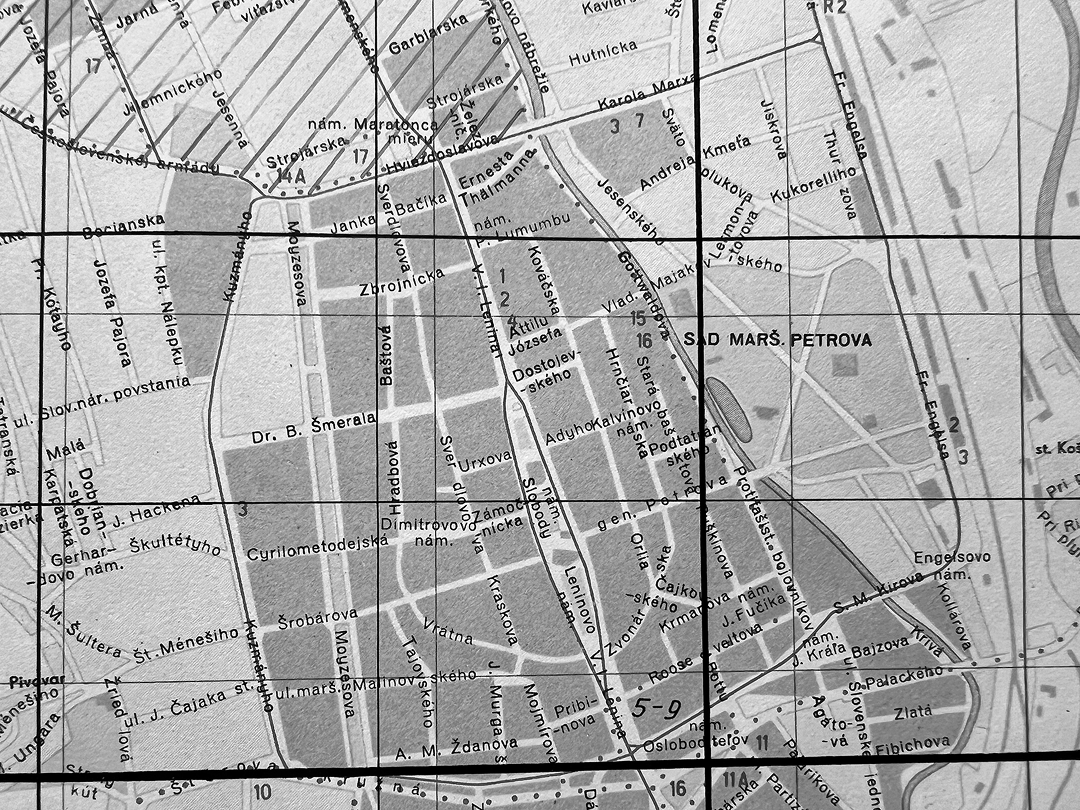

Until the1960s, the east Slovak city of Košice displayed a ring road system, largely inspired by the models of Vienna and Budapest. During the 19th century, local city planners respected the natural interaction between the densely built-up structure and its adjacent recreational area to the east, consisting of the river canal, called the Millrace [Mlynský náhon], the City Park [Mestský park] and the garden-city neighbourhood of the New Town [Újváros], generously incorporating these areas into the inner urban circle. This original concept was still unchallenged in the 1950s, when Košice’s newly ascribed status of the industrial metropolis for the easternmost part of socialist Czechoslovakia anticipated a modernist remodelling of the local urban landscape. Between 1950 and 1970, Košice grew rapidly from a town of 60,000 inhabitants to a city with 150,000 inhabitants, further projected for a population of 300,000 in 2000.

In 1965, after the establishment of the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Košice, it was this expert body, assigned responsibility for local urban planning, that suggested the change of the original inner-city ring. Based solely on technocratic calculations of estimated traffic volumes, this expert body succeeded in pushing through the idea of abandoning of the eastern section of the original inner circle to replace it with an urban highway, constructed under the narrow street Gottwaldova (now Štefánikova) in the watercourse of the Millrace canal. The realisation of the idea between 1968–1978, approved by the local state authorities, imposed a harsh incision into the previously treasured urban texture of the Košice’s pre-WW2 urban composition, which since its creation has been perceived in local memory as a historical urban design mistake.Based on archival research, the present study examines and questions the socio-economic circumstances and political factors that eventuated in the change of the original concept of the Košice ring road from the 19th century, and resulted in the extant, radically car-oriented, modernist intervention in the urban structure of Košice’s historical city centre.

Introduction

“It was foolish from the very beginning. The more time passes, the more stupid it seems”, ran the comment on the replacement of the Millrace by the Gottwaldova highway from long-time architect Alexander Bel, who worked in the urban planning department of the socialist project institute Stavoprojekt Košice between 1964–1991.1

“It is impossible to calculate how much picturesqueness was lost in the environment of the Millrace,” confesses architect Viktor Malinovský Jr., who worked in Stavoprojekt Košice between 1977–1989. He believes the destruction resulted from a cascade of mistakes, a combination of “young architects’ enthusiasm for automobilism” and political decisions.2

Architect Agnes Hoppanová, who joined the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Košice as a junior planner in 1974, confesses that the loss of the water, the drying out of the trees, and additional analysis of other negative impacts – all caused, at that time and specifically for her generation, “a trauma everybody talked about.” She admitted the destruction was the responsibility of the first chief architect of Košice, Ladislav Greč, since for his generation it represented a practical solution of a problem.3

Jozef Proissl, an architect working for Košice’s chief-architect office since its foundation in 1965, refused to comment when asked about the destruction of the Millrace. In his memory, Ladislav Greč emerges as a talented professional well up to date with global trends in the profession.4

“The Millrace has been much praised nowadays, yet it was essentially a sewer. It was not as idyllic as it has been depicted recently”, confesses Jozef Drahovský, vice-president of the International Union of Architects between 2005–2008, and Košice’s chief architect from 2007 to 2011. His own standpoint is more pragmatic: “I am not saying the liquidation was positive, but transport was assigned preference.”5

A similar standpoint expresses the long-term architect of the urban planning department of Stavoprojekt Košice, Dušan Hudec: “It must be said that the Millrace was in a bad condition,” adding, “regarding the traffic, the existing solution has proved effective.”6

Despite these differences of professional opinion regarding the destruction of the Millrace in Košice, the topos of the loss of the water-space and the absence of a river corridor has figured in local collective memory as a triggering issue in civic as well as professional debates over local urban planning since the fall of the regime of state socialism in 1989. The 2024 proposal of the general city plan presents an ambition to “bring the water back” by creating the “New City Centre” on the brownfield sites on the banks of the central section of the river Hornád.7

The civic association Mlynský náhon – named after the vanished physical feature of the Millrace – has even launched a campaign to restore the destroyed watercourse, utilizing current trends and potential funds in reintegrating water for urban well-being, with open

discussion over the alternative route for the existing urban highway.8 A member of the this association, Juraj Tabiczký, decries the liquidation of the Millrace as “a crime and punishment”.9

Despite this phenomenon and its vital role in ongoing participative urban planning in Košice, little is known about the circumstances of such a crucial urban transformation. Such obscurity is striking for an effort that severely affected several urban forms in the central area of the city, including the original design of the inner ring road, the water space represented by the river canal, i.e., the Millrace, and the 19th century bourgeois avenues Barkóczy Street (today Protifašistických bojovníkov) and Bocskay Ring Road (the no longer extant Kirovova Street).

In this microhistorical study, I aim to analyse and evaluate the factors contributing and leading to this urban transformation. Firstly, I attempt to embed the creation of the urban highway Gottwaldova Street in the context of contemporary urban planning on a worldwide scale, as well as the specific case of socialist Czechoslovakia. Secondly, based on the existing literature, I attempt to explain the intrinsic logic of the original design of Košice’s inner city ring road, the urban form into which the river canal was inserted. Thirdly, I survey the increasing power of planning institutions and practices, which led to the creation of the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Košice, and the ability of employees of this professional body to persuade local decision makers to push forward the river canal’s replacement by an urban highway.

In this study, I employ a historically informed approach to planning research, analysing archival resources from the Archive of the City of Košice, the State Archive of Košice, and the Slovak National Archive in Bratislava, as well as articles in the contemporary press.

Furthermore, I use in the present work the term “urban highway” for a type of a four-lane urban road that carries vertically segregated traffic, typically concealed, half-concealed, elevated, or half-elevated. Other synonyms, depending on culturally-linguistically conditioned preferences, are motorways, expressways, and freeways.

Urban Highways as a Paradigmatic Urbanistic Solution to the “Motor Age”

The rise of the private car and automobilism as a social phenomenon radically affected town planning, and still does. The car-centric approach of the modernist urbanists supported vehicle access into pre-modern urban fabric through insertion of traffic corridors, whether wide boulevards or urban highways.10 This feature became notably prevalent in the United States and Canada in the 1950s and 1960s, rendering the urban highways the hallmark of the North American city.11

Similarly, the car-centric modernist paradigm was equally followed by the planners in Europe. Probably the most radical examples of a use of an urban highway as a substitution for a non-existent or non-functional inner ring road are in certain British cities: Glasgow (1965–1972), Leicester (1965–1974), and Leeds (1964–1975). These massive projects requested demolition of whole urban blocks, which resulted in significant changes to adjacent urban structures.12

In the Netherlands, a respect for the historical heritage of the extant urban fabric forced local engineers to invent subtler, yet equally radical interventions in the existing urban structure. In Utrecht, they enabled cars to easily reach the commercial facilities constructed on the outskirts of the historical city centre by replacing the Catharijnebaan, a medieval river canal, with a 12-lane-highway (1971–1973).13

Regarded internationally as a synonym for a notably failed urban highway is the Central Artery in the American city of Boston. Partly elevated and partly tunnelled, this north-south transversal became, shortly after its construction in 1959, associated with many of the negative effects of urban highways, such as destruction of neighbourhoods, displacement of residents, creation of unhealthy environments, lowered property values, air and noise pollution, disinvestment, and suburban sprawl. Due to rising civic opposition, construction of many of the planned urban highways in the United States was successfully halted.14

Since the 1990s, there has been a growing interest in removing highways and replacing them, thus repairing social divisions in urban space and fostering more sustainable mobility.**key=15** The Central Artery in Boston was placed under a covered surface in the Big Dig project (1991–2007), while the municipality of Utrecht managed to restore the Catharijnebaan river canal (2015–2020).

For the present study, however, the most urgent question is somewhat different: was the dream of free-flowing traffic circulating through the city organism equally prevalent among city planners in the socialist states of the East Block?

Citing the authors of the volume The Socialist Car, it can be argued that the shared agenda of the international expert community on the design of urban space as an efficient tool for communications informed the thinking of professional planners in capitalist and state socialist countries alike.16 In socialist Czechoslovakia (1948–1989), the quantity of road transport rose yearly by 8–9% between 1949 and 1965. Such an increase accelerated the completion of urban motorways in both Prague and Bratislava, which had been planned even before the end of WWII. Prague built its most significant urban motorway in a form of a partially elevated north-south transversal (Severojižní magistrála II., 1958–1980),17 whereas Bratislava used the even more radical form of a through highway breaking through the historical city centre to connect it with the newly developed housing estate of Petržalka on the south bank of the river Danube.18

East Slovakia – the most backward Czechoslovak region, where Košice constituted the natural metropolis – gradually caught up in terms of automobilism with the rest of the republic (an annual increase of as much as 23.6%).19 Rising in parallel with the economic and geopolitical significance of Košice was the necessity for improvement of its architectural and urbanistic morphology. This feature was not considered satisfactory by members of the county committee of the Slovak Communist Party: for the party representatives, architecture and urbanism bore as much an economic as an ideological legacy. In 1964, the committee attacked the municipal authorities, urbanists, and architects over the poor quality of projects, public spaces, and the lack of road corridors, and expressed concerns regarding the backward appearance of urban spaces: “Workers are asking righteously questions … they compare, even if they see something on the television, in movies etc., and inevitably created is in their imagination an even more critical projection of what they see at home.”20 Such a socio-political force paved a road – not only metaphorically – for the realisation of radical interventions in Košice’s road network.

The original Košice Ring Road

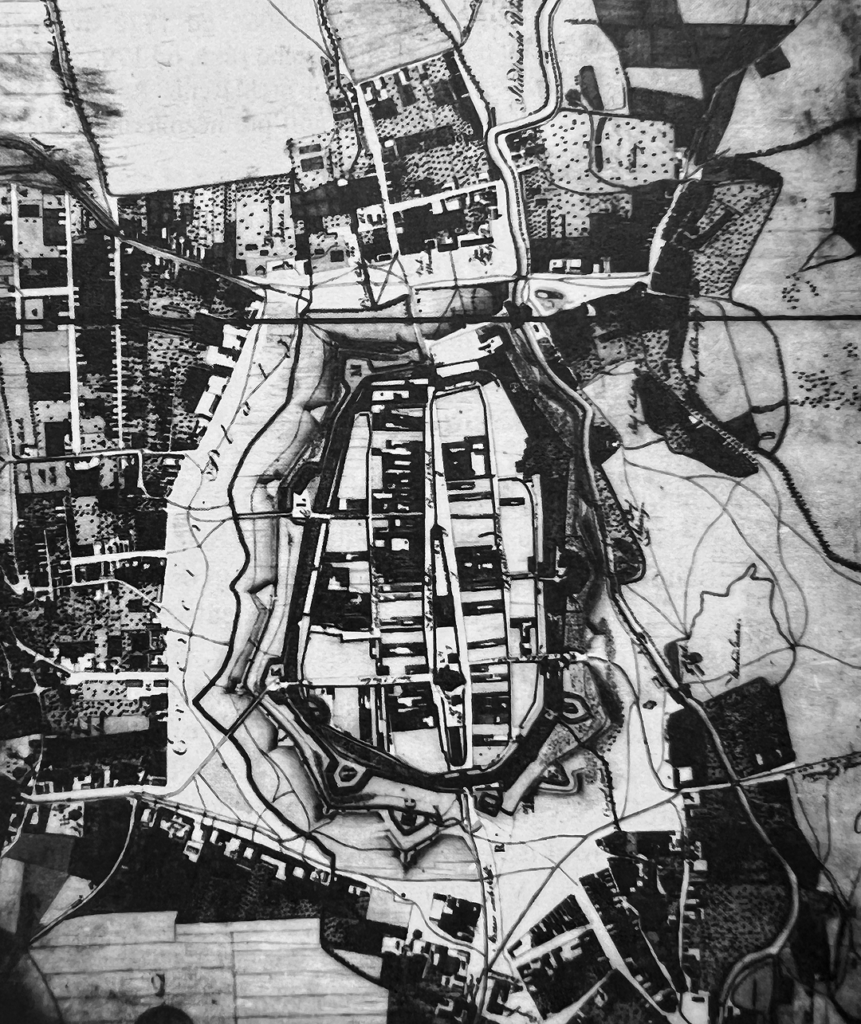

The original Košice ring road was formed by several significant urban structures originating from the medieval and early modern urban development of the city. Similarly to Vienna, the city of Košice served as a significant military fortress – “Festung”. This status required the city to be defended with bastion fortifications, complemented with wide slopes – the glacis. For this reason, any additional suburban structures by necessity arose at a significant distance from the fortified city, i.e. roughly 250 metres away.21 At the same distance from the city proper were the emerging local circular roads, which interconnected the main radials from the direction of Buda and Pest (now Južná trieda), Krakow (now Prešovská cesta), Rožňava (now Štúrova Street) and Spišská Nová Ves (now Komenského Street and Stará spišská cesta). As depicted on the 1807 plan of Austrian military officer Johann Nepomuk von Chunert, these circular roads formed the inner building lines of Košice’s southern, western and northern suburbs, and as such, anticipated the future shape of Košice’s inner ring road.22

The abolition of the “Festung” status for Košice by the Austrian emperor Joseph II in 1783 opened the potential for the extension of the city. The first expansion occurred during the 1830s and 1840s by lengthening of the Main Street [Hlavná ulica] both northward and southward, forming nodal spaces at the intersections of the radials with the suburban circular roads. This tendency stemmed from the spatial and functional dominance of the city’s Main Street [Hlavná ulica], which has persisted in the urban structure of Košice over the centuries. Considering that this narrowly elliptical street, almost 1 km long, was designed in the 13th century, this compact public space could be considered – relative to Central-European standards – an urban form of grand scale in both its width and length.23

The lengthening of the Main Street and its joining with the original routes of suburban circular roads resulted in the rapid expansion of the perimeter of the future ring road system. As a result, while some other cities in the historical Hungarian realm have their inner rings designed as encirclements of their medieval urban structures, e. g. Timişoara, Sopron, or even Budapest (the Small or Inner Ring Road [Kiskörút]), Košice represents the city type with an extended inner ring, inside of which the medieval urban structure was continuously complemented by modern, 19th-century urban development.

Košice’s decisionmakers, i.e. local authorities and investors, achieved this result through the gradual implementation of the municipal plan from 1841, the work of the German-speaking private engineer Joseph Ott. The plan anticipated the creation of a strictly regulated urban structure on the site of the ex-glacis to the west of the medieval urban structure, thus applying a regular grid in the newly developed street network. The grand-scale parameters of Ott’s plan appear most evident in his planning of the buffer zone between the inner city and the western suburb, which consisted of two parallel ring roads (now Moyzesova and Kuzmányho Streets), creating a sufficient space for representative edifices and a park promenade.24

Urbanization of the area on the eastern side of the pre-modern built fabric of the city was much more complicated, due to the presence of the river canal and city park. The river Hornád adjoined the fortified city to its east by means of a river canal: the Millrace [Mlynský náhon]. The ditch not only functioned as a water link, but had significant economic functions (city gristmills, farmsteads), and in the modern era also a recreational ones (baths, city meadows, the Fišerka fairgrounds). This functional symbiosis between the city and the river canal was respected by the municipal authorities in 1860, when it was decided to route the railway corridor not in the proximity of the urban built-up area, but instead beyond the river-canal hinterland.25

When creating the eastern section of the inner ring, local decisionmakers basically had two options. The first was to create a ring road between the pre-modern urban structure and the canal river, thus essentially resulting in a boulevard along the embankment. This option was supported by the construction of the boulevard-style Barkóczy Street (now Protifašistických bojovníkov) with four rows of trees. However, for it to continue on the same scale northward, beyond Mlynská Street in the proximity of the river canal (now Štefánikova Street), it would require a new, more generous street line, set back to the west. Since no such regulation was implemented, the embankment street was designed as a simple, local, two-lane, narrow road.

The second option implied copying the “expansion pattern” used in the western part of the inner ring, thus crossing the river canal and encompassing the city park area, reaching the railway corridor. It was this second option that was eventually chosen. The northeast corner of the expanded ring (now between Masarykova and Bencúrova) was offered for development in a form of a prestigious garden neighbourhood, named New Town [Újváros].26

The completed ring road, geometrically resembling a regular quadrate, became a significant compositional unit within Košice’s urban structure. With its predominant transport function, it interconnected nodal intersections with radials, adjacent suburb areas, as well as the railway station by means of a ring tram line.

“The Millrace Will Be Retained as a Popular Water Area in the City”. Cultivation of the Eastern Section of the Inner Ring Road after WWII

After WWII, the original concept of the Košice inner ring road was further cultivated within the system of a radial-ring scheme of a street network. The 1951 study for a general city plan by Czech architect Bohuslav Fuchs anticipated the creation of an outer ring road, later copied in every other general city plan and eventually completed by the late 1960s.27

The transportation function of the eastern section of the inner ring road could have been further reinforced by the planned creation of a central-eastern tangent (today streets Vodárenská – Slovenská – Stromova – Bencúrova – Krivá – Jantárová). Routed parallel with the railway corridor, it would have provided sufficient connection of the northern residential areas with the southern industrial zone, thus a highly useful alternative to the dominant north-south city axis (today Komenského – Hlavná – Južná trieda).

The 1953 general city plan by Czech architects František Kočí and Jiří Hrůza proposed to complement the above mentioned central-eastern tangent by a semi-middle ring road (today streets Stromova – Slovenskej jednoty – Letná in the north, and Krivá – Jantárová in the south direction). This middle ring road was supposed to share a mutual section with the eastern section of the inner ring road (today Bencúrova Street), and as such to connect the newly developed residential housing estates, built in the style of Socialist Realism (Košice I, Košice II), with the railway station. Serviced by a semi-circular trolleybus line, it was supposed to function as an efficient route to feed the most important transportation hub, primarily to allow workers to commute to the proposed metal works HUKO (Hutnícky kombinát) on the southern outskirts of the city.28

The 1953 general city plan respected the original texture of the urban structure around the eastern section of the inner ring road. In the plan, the Millrace figured as a “green avenue,” which would create a continuous green axis connecting the city centre with the northern forest parks.29 In municipal reports from the 1950s, the Millrace was depicted as a favourable and attractive recreational component of the urban environment: “The Millrace will be retained as a popular water area in the city, as it is also usable for minor sports activities.”30

However, due to the failure of construction of the HUKO metal works in 1953–1955 (replaced by the East Slovak Metal Works in the 1960s), the 1953 general city plan, now considered outdated, was never approved by the government.31 Its short existence halted realisation of highly needed if minor interventions into the street network of Košice, which would significantly have improved its somewhat confining grid-logic. For example, creation of the half-ring road would require several insertions of new, geometrically balanced street connections, namely between Chalúpkova – Slovenskej jednoty, Slovenskej jednoty – Stromova, and the intersection Bencúrova – Palackého – Krivá. Also, the failure of conceptually harmonising this plan with the simultaneous redevelopment of Košice’s railway node, i.e. its new passenger building and adjacent railway-station-site, postponed solution of the problem to the 1960s.32

The function of the eastern section of the inner ring road was supposed to be further reinforced in the 1958 study for a general city plan, drafted by local architects employed by the state institute Stavoprojekt Košice, Ladislav Greč and Ján Gabríny. Their proposal anticipated urban sprawl arising as well in the east direction of the city beyond the railway corridor. For a compact connection of the proposed eastern developments with the city centre, the two architects doubled the parameter of the northern section of the inner ring road and created a dominant east-west axis, consisting of two parallel avenues, lined in the middle by significant civic amenities (Hviezdoslavova – Masarykova and Strojárenská – Hutnícka). Even though the plan was never officially approved, its ideological influence fell on fertile ground when the city authorities decided to bulldoze an entire street block on the bank of the Millrace (between Masarykova and Hutnícka Street) and built on its site the imposing modernist House of Trade Unions (1959–1968).33

At the same time, the 1958 Greč – Gabríny study influenced the construction of housing estates on the northern outskirts of the built-up urban structure (Mlynský náhon, named after the river canal; Mier, Sever, and later Podhradová), as well as the southern outskirts (the housing estate Juh). This growth resulted in the gradual re-enforcement of the north-south gravity centre of the urban structure of Košice, which required efficient traffic corridors as alternatives to the dominant south-north axis Komenského – Leninova (today the Main Street) – Trieda Sovietskej Armády (now Južná trieda). Such an alternative city road, as a new radial parallel to Komenského Street, was created in the axis Gorkého Street – Národná trieda. This new radial intersected the inner ring road at the same nodal point, at which Gottwaldova Street (now Štefánikova) directly continued as a parallel alternative to the Main Street, and further to the southern neighbourhoods. In the 2nd half of the 1950s, with the rise in private car ownership and the routing of two heavily used bus lines through Gottwaldova Street, the local authorities started to invest in improvement of this section, arguing that it would ease the traffic in the Main Street.34

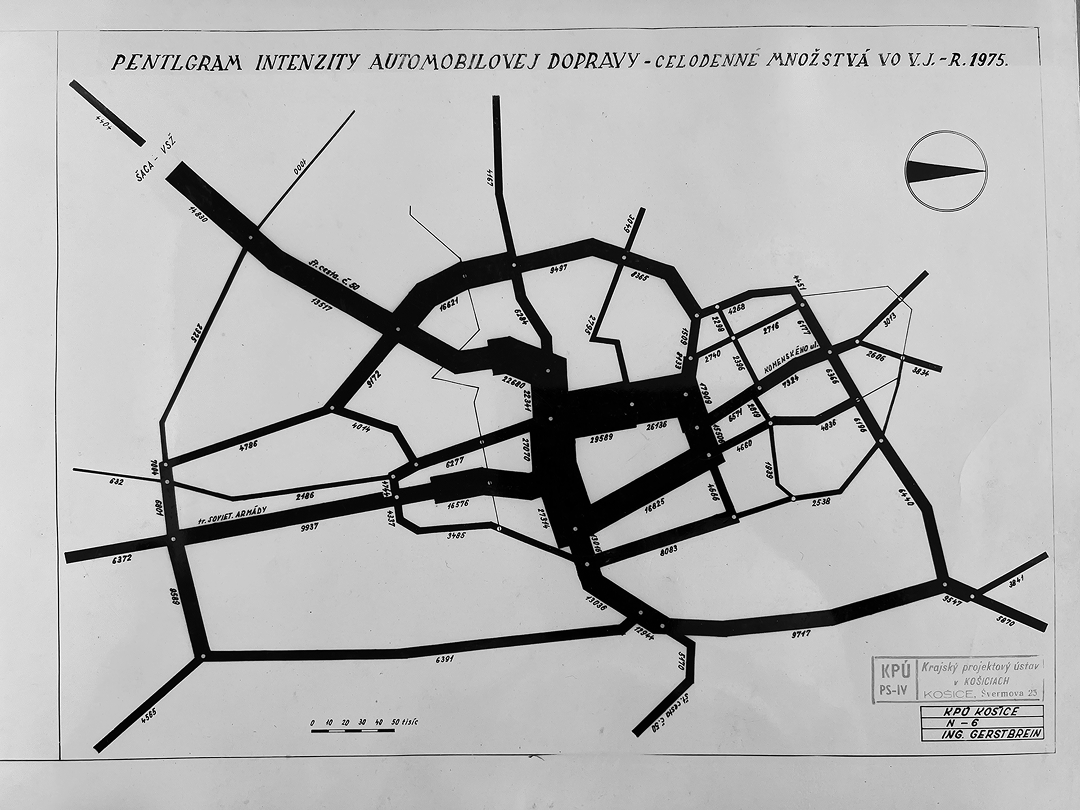

The consequent, 1959 general city plan of Košice, under the guidance of Michal Hladký, from 1962 to 1964 the chief architect of Bratislava, already reflected the shift in the hierarchy of Košice’s road network. This plan, where the transportation expertise was elaborated by Košice’s transport expert Vojtech Gerstbrein, featured a visibly car-oriented approach in urban planning. Gerstbrein proposed a fly-over expressway in the direction from Prešov to the newly built East Slovak Metal Works (now Hlinkova – Watsonova – new section under the Nové Mesto housing estate – Moldavská). This expressway was to be complemented by a network of arterial radial roads. An expert group of Soviet urbanists, however, questioned the justification for Gerstbrein’s expressway, preferring instead Štúrova Street as the main urban transversal. Under the influence of the Soviet experts, the 1959 expressway remained only a surrealistic dream of the “motor age”.35 The role of the western section of the outer ring road was then assumed by the north-south transversal through the modernist housing estate Nové Mesto (now Trieda SNP).

At the same time, the Soviet experts suggested the accentuation of the eastern-central tangent along the railway corridor, outlined already in Fuchs’s 1951 study, which would supply the eastern section of the ring road as a path of mass transportation and goods, as it was directly connected to the rail facilities and a bus terminal. However, its realization has never come to fruition (except for the southern section – Jantárová Street).36

Nevertheless, it was Gottwaldova Street, named after Klement Gottwald, the first Communist president of Czechoslovakia, that was identified in the 1959 general city plan as one of the arterial roads: “Gottwaldova Street, which helps to unburden the city centre, is adequately regulated by the general plan, and after its intersection with Marxova Street (now Masarykova) it has a continuation in the National Avenue [Národná trieda] and further into the housing estate Mier.”37

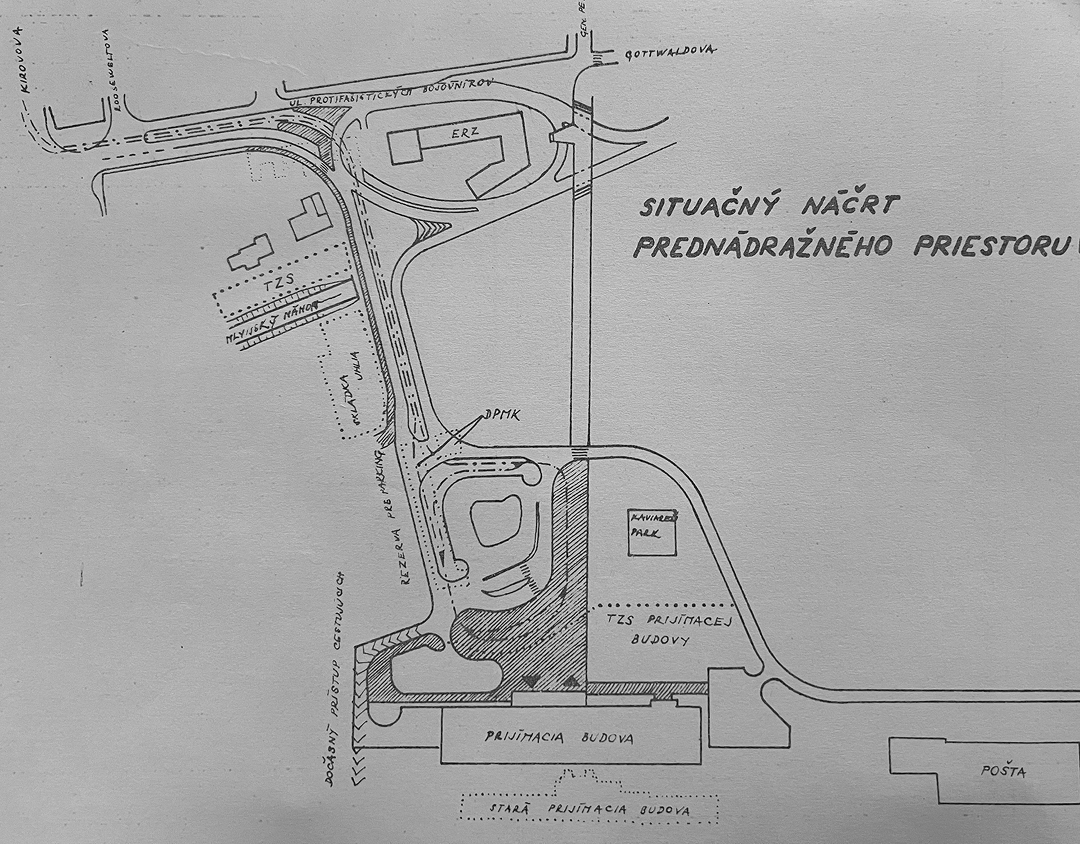

Even though Gottwaldova Street gradually replaced the eastern section of the inner ring road as an important arterial road, in the 1959 general city plan the inner ring road was preserved in its original design, and, as such, scheduled for a major reconstruction. This retention stemmed from the pressing need to redevelop the area near the rail station (Prednádražie), which, according to state authorities, required construction of a completely new, high-capacity passenger terminal. Its construction site needed to be advanced westward from the outdated historical railway station building, hence taking a considerable slice from the substance of the 19th century city park.38

Under the threat of the loss of 1.5 ha of the green space, following protests by hygienists and conservationists, the architects were forced to come up with a two-level, grade-separated concept of the station site. The final design of the terminal was monitored by experts from the Transport Ministry in Prague and members of the regional committee of the Communist Party. In 1961, they ordered an architectural tender. A final draft of the architectural-urbanistic study, based on the proposal of the Regional Project Institute for Košice [Krajský projektový útvar] outlined an airport-like terminus provided with two-level entrances. On its first level, it was supposed to accommodate a highway ramp carrying a four-lane ring road with tram tracks in the middle, whereas its ground-level was supposed to be dedicated solely to a car-free, main pedestrian axis, open to the city park and city centre.39

The draft would not be comprehensive without a solution for its complex incorporation into the existing traffic network. This was provided in 1962 by transport expert Vojtech Gerstbrein of the Regional Project Institute for Košice. In his proposal, he adhered to the existing road network, though differentiated between the inner ring road (Engelsova – Kirovova) and the main urban transversal (Štúrova – Palackého) prioritized by the Soviet experts. The intersection of these two traffic structures was to occur at the Liberators’ Square [Námestie osloboditeľov] by an underpass of the latter.40 For the first time, a grade-separated solution was proposed for the most exposed and multifunctional nodal point of the city, yet it never came to fruition.

At the same time, i.e. between 1960 and 1965, two decisive circumstances halted the plans, while in 1964 by local authorities approved realization of the two-level concept of the railway-station-site. Namely, the massively dynamic construction boom in socialist Czechoslovakia at the turn of 1950s and 1960s rendered a necessity for more consistent planning regulation. The rise of a strictly technocratic approach in planning, focused on functionality, hygiene and quantity, involved the elaboration of analyses of several alternative solutions, their economic calculation, and, finally, evaluation.41

Regarding existing general city plans, governmental authorities questioned their poor analysis of growing transportation needs in urban environments. Therefore, in 1960, orders were implemented for further transportation analysis, termed “general plans of transport,” specifically for bigger Czechoslovak cities such as Prague, Bratislava, Brno, Ostrava, Košice and Ústí nad Labem.42

The elaboration of Košice’s general plan of transport was assigned to the Regional Project Institute for Košice, under the guidance of its transport expert Vojtech Gerstbrein. Openly avowing his admiration for a car-oriented approach in urban planning, he went so far as to suggest a complete withdrawal of trams from the streets of the city.43

Another significant circumstance affected the ongoing course, but this time not only halting the two-level concept of the railway-station-site, but also affected the original concept of the inner ring road. Czechoslovakia’s prevalent technocratic approach in urban planning inspired the creation of a professional umbrella body, empowered with both expert and executive competencies in urban planning in every bigger city of the country, entitled the “Office of the Chief Architect.” After Prague received one in 1961, and Bratislava in 1962, the government ordered the establishment of one in every major city, including Košice. The Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Košice, starting operation in February 1965, employed several of the most active local professionals in the field of architecture and urbanism, previously dispersed among several project and design institutes with no decision-making competences, such as Ladislav Greč, who became the first chief architect, Ján Gabríny, but also transportation expert Vojtech Gerstbrein.44

The Change of the Concept of the Inner Ring Road

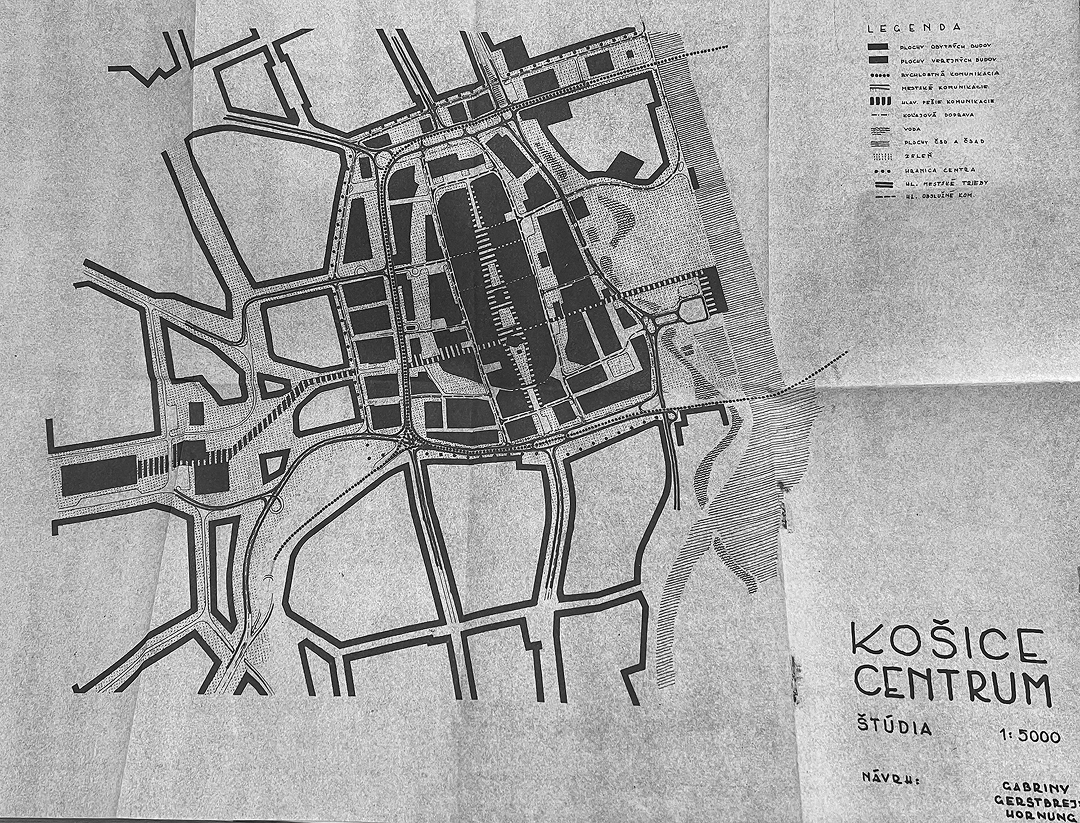

Immediately after the creation of the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Košice, this group of professionals contacted the top local decision makers in the then hierarchy in state construction – the East Slovak Regional National Committee. They attempted to persuade this top body to abandon the original idea of a four-lane ring road next to the railway station, arguing that the results of the general plan of transport showed the passing of through traffic between the northern and southern neighbourhoods running via Gottwaldova Street. Therefore, if any of those roads had needed to be upgraded, it would have to be Gottwaldova Street. However, as Gottwaldova Street had a narrow profile, they proposed to build a substitute corridor in a form of an urban highway in place of the river canal, the Millrace. A connection to the railway station site as a terminal transportation space was to be provided by a street inserted from Protifašistických bojovníkov.

Further, the group claimed that the new concept had significant advantages over the original plan, such as a more workable zonal dispersal of passengers, separating the flow of pedestrians, mass transport, and dynamic and static individual transport within a one-level concept of the railway-station-site. Additionally, they cited the major limitation of damage to the city park, the creation of a continuous grade-separated pedestrian axis “railways station – city centre”, and most importantly, lower costs: only 22 million Czechoslovak crowns against the previously assigned 32 million.45 Their argumentation thoroughly matched the contemporary international trend toward vertical segregation of different modes of transportation.

The regional authorities requested a standpoint from the Slovak Committee for Investment Construction in Bratislava. Representatives of this expert body did not reject the new concept, but did question the calculation of costs and whether the disruption of the city park would be as minor as claimed.46

Furthermore, the East-Slovak Regional National Committee obtained two more expert opinions. The first, transport expert Zdeněk Kapoun of the Office of the Chief Architect of the Capital City of Prague, approved the concept of Košice’s chief-architect-group, arguing:

“The traffic load will be directed into one major route, classified minimally as a Class A highway. The main function of this route is servicing the city centre; therefore, it appears that its correct location should be on the central perimeter with a minimal distance from the city centre. Maximal shortening of targeted drives, categorized into respective nodal points of the ring road, will be markedly manifested in the evaluation of the operational economy.”

At the same time, he argued that the urban highway would cut 4–6 m from the city park, and that its construction would be 30–50% costlier than the proposal of the Košice chief-architect group.47

The second expert, Tomáš Horallek of the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Bratislava, noted that from the urbanistic point of view, the destruction of the river canal would mean a certain loss, yet found the new concept essentially correct. Similarly to Zdeněk Kapoun, he criticized the multiple branches with ramps to and from the highway, proposing their reduction. According to his calculation, the new concept would be costlier at least by 50% in comparison to the original plan:

“Considering that, according to the water resources management, the level of the future roadbed will lie under the groundwater surface, it is necessary to make allowance for further increase in investments, the calculation of which cannot be estimated at this point.”48

In November 1965, chairman of the expertize department of the Slovak Committee for Investment Construction in Bratislava František Záriš expressed his concerns regarding megalomaniac tendencies of the concept and its overall costs:

“The concept of a road in the Millrace watercourse is – regarding the real needs within the conditions of the city – conceived on an unusually grand scale. The idea of constructing eight fly-over crossings over a distance of 1200 m not only outstrips our economic capabilities, but also the real need for this given section of the inner ring, without any significant long-distance traffic.”49

Despite these major reservations, experts from outside Košice, working in considerably more metropolitan environments, basically agreed on the building of a highway in the riverbed of the Millrace. Under these circumstances, the council members of the East Slovak Regional National Committee approved the concept of Košice’s chief architect group. The realization of the railway-station site was calculated with a budget of 16,5 million Czechoslovak crowns and scheduled for 1968–1969, whereas Gottwaldova Street, with a budget of 18,5 million, was scheduled for 1968–1970. The urban highway, 1000 m long and 14 m wide, placed in a traffic channel 5–6 metres deep with five grade-separated bridge objects, was projected with a capacity of 40,000 vehicles per day. Its main function was described as a main delivery ring and, at the same time, an arterial tangent, which would help to create a proposed pedestrian zone in the Main Street.50

Due to the significantly more complicated cycle of operations in constructing a highway in place of a river canal, a specialized firm was chosen as general projector, the Metallurgic Project – State Institute for the Design of Metallurgical Complexes [Hutný projekt]. Immediately, the corporate representatives notified the investor that the new concept was, from the very beginning, incorrect, being far too costly. In comparison to 1 km of an interurban highway, the cost overruns exceeded 100% because of its bridges, massive retaining walls, and pressure piping for diverting the water from the Millrace. Further, they pointed out that the planners did not take into account the ongoing liberalization of wholesale prices, meaning that the liberalization processes of the Prague Spring would imply greater costs, and the return on investment was calculated to occur only in 1985, instead of the desired date of 1970. Ultimately, they labelled the action as “oversized”.51

Rising uncertainties over financing and organizational quarrels delayed the highway’s realization, along with disputes with the East Slovak Electricity Company over their request to relocate their head office, becoming isolated by retaining walls of the urban highway, which was eventually refused. In April 1968, the investor, the East Slovak Regional National Committee, was forced to re-evaluate the grand-scale concept of Košice’s chief-architect group, as the costs had risen to a staggering figure of 43.3 million crowns. Compromise was achieved by eliminating two of the five bridges: one between Podtatranského and Vodná Street, and one at Kmeťova Street. More importantly, the roadbed level beyond the bridge at Mlynská Street was raised by 2 meters, shifting the base plate of the retaining walls above the groundwater level. As the prefabricated bridge at Kmeťova Street was no longer included, the whole section was raised to ground level, which helped to cut the budget by 10 million.52

However, in 1969, after the government temporarily dissolved the administrative system of regions in the Slovak part of Czechoslovakia, the role of the sole investor was undertaken by the Košice municipal government, which was hardly capable of pushing the project to completion. Even though the city representatives attempted to accelerate acquiring resources from the state authorities in Bratislava, they only succeeded in connecting the city centre with the new railway station, completed in 1973, with a simple two-lane road in a cost of 5 million.53

In fact, disagreement and argumentation followed the new concept along multiple fronts. It was the representatives of the Eastern Railway Directorate [Správa východnej dráhy] who already in 1965 announced that the new concept of the inner ring via Gottwaldova Street would not actually mitigate the partial destruction of the City Park, but instead expand it.54

Another example of a discrepancy occurred when a member of the public – within a moderated public debate – asked chief architect Greč about the definite outlook of the original, grade-level Gottwaldova Street. Greč provided an answer: “At this time, we are preparing redevelopment of Gottwaldova Street in the sense that it is too narrow for traffic, therefore, a park will be created on its place.”55 In reality, the original street was redeveloped as a two-lane road.

In addition, Greč successfully denied any objections against an auxiliary road in the north direction from the railway station (today Thurzova street), which was supposed to connect the new Post Office Košice 2 with the railway station. Reservations against this auxiliary road were already expressed in the expert reports by both Zdeněk Kapoun and Tomáš Horallek. This newly created road not only significantly reduced the green space of the City Park but in fact disrupted the originally intended grade-separated pedestrian axis.

At this point it should be stressed that chief architect Greč played a pivotal role in the design of the newly created urban highway at Gottwaldova Street and the adjacent sites. Namely, due to the grievously complicated network of investors and planners involved in synchronous redevelopments connected to the railway-station site, on 7th December 1965, the East Slovak Regional National Committee appointed Greč as responsible for coordination of all ongoing actions.56 He managed to maintain this strong post for a period of six years. However, in 1971, the Municipal National Committee of Košice withdrew him from the post of chief architect, and he was furthermore dismissed from the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Košice “as a result of several collisions in urban planning management and several severe shortcomings in management and working morals at the Office”, as stated in the minutes of the municipal committee.57

Unlike Greč, the incoming chief architect Viktor Malinovský Sr. did not appear a fan of the urban highway in the city centre. In a representative publication about Košice from 1975, he wrote: “Rivers have been always attractive for architects, urbanists, and urban populations. Our generation broke away from the river Hornád, or turned the water away from Košice. She exchanged the river-bed of the Millrace for the solid object of a future highway, and the banks of the river Hornád have been overgrown by industrial and railway facilities.”58 At the same time, he emphasised that the remaining section of the Millrace up until Marxova Street (now Masarykova) would be restored and filled with water.

At a time of the economic consolidation of the post-Prague-Spring governmental policies, it took up to 1978 for the completed Gottwaldova urban highway to be opened for traffic.59 As a result of chronic construction delays, local authorities were forced to face certain civic opposition from the public. Moreover, when censorship was rescinded during the Prague Spring in 1968, local newspapers published several critical voices which questioned the logic of the construction works. The canal had been dried already in 1967, with no ongoing construction works for years to come. These nostalgic articles openly called upon authorities to reconsider their “wrong” decision, and questioned professionals about how they could had allowed such a misstep: “How could the county hygienists approve this? Or were they forced to?”60

However, critical voices were silenced after the suppression of the liberalization processes in Czechoslovakia in August 1968, while the new regime attempted to persuade locals of the modernity of the future Gottwaldova Street. Local newspapers started occasionally publishing pictures from West European cities where urban highways were under construction, such as Hannover and Wuppertal, and presented these as “proud achievements”.61 The article titled “Košice’s “underground” under construction” presented the urban highway Gottwaldova as an urban form that would theoretically contribute considerably to the metropolitan status of Košice.62

The ideological utilization of the constructed Gottwaldova Street also echoed in art. Paintings by Ernest Zmeták in 1975 and Andrej Doboš in 1977 both depicted the construction of the highway. According to curator of the East Slovak Gallery Miroslav Kleban, archetypes of a road and a construction site both represented typical motives of socialist realism (which in art history applies terminologically to the entire period of the state-socialist regime). Thus, these depictions should be interpreted as expressing the transformation of the town into a modern socialist industrial city.63

Conclusion

The Gottwaldova urban highway, it must be said, offered a long-term solution to the traffic problems of the Košice city centre, and significantly helped in ensuring the pedestrianizing of the Main Street in 1984.

On the other hand, the destruction of the central section of the Millrace brought tangible negative impacts. The city lost its intimate contact with any watercourses, as well as a large part of its green space. Compositionally, the highway separated the city centre from the City Park, while harming environmental conditions in the adjacent area, now burdened with increased traffic noise and air pollutants. After the drying of the Millrace, the pool basin fractured in the adjacent swimming pool complex at Rumanova Street, itself designed by Ladislav Greč in 1959, and the facility needed to be permanently closed until its renovation as the city Kunsthalle in 2013.

In parallel, the highway changed the local mental map of the urban structure beyond the highway. The previously prestigious garden-city neighbourhood became gradually deprived, with all negative manifestations typical for post-socialist marginalized territories, such as concentration of anti-social behaviour, criminality, and prostitution. In this respect, the Košice case registers clear similarities with U.S. cities.

When evaluating the 1965 decision to build an urban highway on the site of a historic river canal, one needs to consider several factors that enabled such a radical developmental trajectory. The 1965 concept of the Košice chief-architect group offered, for its time, a very trendy and modern solution for the modernisation and metropolisation of the city. And the more infrastructural issues it promised to solve synchronously, the more attractive it appeared. Among these questions were the simplification of the redevelopment of the railway-station-site, delayed by over a decade, the capacity enhancement of the inner ring, and the acceleration of traffic flow between the northern and southern neighbourhoods. However, local decisionmakers would not give the green light to this concept without registering the opinions of professionals from bigger cities, namely Prague and Bratislava. And their approval of the concept was decisive in its realization.

On the other hand, experts from outside Košice warned that the 1965 concept was too ambitious, if not indeed megalomaniac, for a city of its proportions, with the projected population of only 180,000 by 1975. In this respect, it was the argumentative talent and technocratic enthusiasm of Košice’s chief-architect group that averted a possible refusal or radical reduction of their concept by the local political elites (municipal and regional decision makers).

By doing so, in their argumentative strategy, the Košice chief-architect group used several pieces of information, or perhaps more accurately promises, that turned out false. The underestimation of costs is the most striking example; the other is the extent of reduction of the green space of the City Park, which, at the end of the day, became even larger than the previous concept of upgrading the original ring road. Similarly, the plan for a grade-separated pedestrian axis was disrupted by the auxiliary road leading to the new Post Office Košice 2.

But the primary question to ask regarding the 1965 concept of the Košice chief-architect group is whether the occurred developmental trajectory was inevitable, or necessary.

Firstly, Košice had a functional inner city ring road, though its eastern section needed an upgrade to a four-lane arterial road. The project of the upgrade won approval from the authorities in 1962, and the construction works commenced in 1964, only to be stopped in 1965.

Secondly, the eastern section of the original ring road would not have been partially deprived of its arterial status in favour of Gottwaldova Street, had the decision makers followed previous general city plans and pushed forward the realization of a semi-middle ring road, as well as a proposed eastern-central radial composed of the streets Vodárenská – Slovenská – Stromová – Bencúrova – Krivá. This radial, together with the possible lengthening of Masarykova Street beyond the railway corridor, would have created a nodal intersection with the eastern section of the original ring road, thus reinforcing its arterial status.

Thirdly, the distance between Gottwaldova Street and the eastern section of the original ring road was roughly between 500–1000 m. This distance is negligible against the argument that drivers would prefer Gottwaldova Street as a shortcut. This argument was used by Košice’s chief-architect group in 1965, which was at the time of a pressing solution for a rapid connection between the northern and southern sectors of the city. However, the 1968 revision of the general city plan anticipated the construction of new housing estates (later named Dargovských hrdinov and Ťahanovce) in the eastern sector of the city, i.e. on the eastern bank of the river Hornád, thus shifting the gravity centre of the urban structure of Košice in benefit of the west-east axis. Had the eastern section of the original ring road not been cancelled by the end of the 1960s, it would have provided a more convenient connection of these housing estates with the city centre via the lengthened Masarykova Street over the railway corridor, as it was proposed in every consequent urban planning documentation, including the current proposal of the general city plan (2024).

Even from this point of view, the decision to shorten the inner ring road via Gottwaldova Street appears to be an impulsive, premature, overly expensive, and rather overdesigned solution for a ring road in a proportion to the actual size of the city of Košice. A large part of the local population did not identify with this concept, nor did a considerable number of significant professionals and experts who already in the 1970s decried the concept as a major urbanistic mistake.

The most staggering feature of the concept is the speed at which it was designed by Košice’s chief-architect-group, and consequently approved by local decision-makers. If we recall that similar projects in the U.S. and western Europe were constructed at the same time, or even after Košice’s case, one must admit that realisation of the 1965 Košice’s chief-architect-group’s concept might have appeared in the local environment far ahead of its time. Therefore, it would be interesting to observe whether recently incumbent urbanists and decision makers would have listened appreciatively to the voices for a reversal of the 1965 decision, and, at the same time, have caught up with the trends in contemporary urban planning as promptly as did their predecessors in 1965.

BEL, Alexander. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 29 May. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

MALINOVSKÝ, Viktor Jr. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 5 June. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

HOPPANOVÁ, Agnes. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 5 June. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

PROISSL, Jozef. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 11 June. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

DRAHOVSKÝ, Martin. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 12 June. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

HUDEC, Dušan. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 1 July. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

OPEN DATA KOŠICE. 2024. Návrh územného plánu. Mesto Košice [online]. Available at: https://opendata.kosice.sk/pages/navrh_uzemneho_planu (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

MLYNSKÝ NÁHON, O. Z. 2024. Mlynský náhon [online]. Available at: https://mlynskynahon.sk (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

TABICZKÝ, Juraj. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri and Petronela Šelinger Királyová, 31 July. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

DECKKER, Thomas. (ed.). 2000. Modern City Revisited. Taylor & Francis.

DIMENTO, Joseph and ELLIS, Cliff. 2012. Changing Lanes. Visions and Histories of Urban Freeways. Cambridge: MIT Press.

LARKHAM, Peter J. 2020. British Urban Reconstruction after the Second World War: The Rise of Planning and the Issue of “Non-Planning”. Architektúra a urbanizmus, 54(1–2), pp. 20–32. doi: 10.31577/archandurb.2020.54.1-2.2; MELLER, Helen. 1977. Towns, Plans and Society in Modern Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BOFFLEY, Daniel. 2020. Utrecht restores historic canal made into motorway in 1970s. The Guardian [online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/14/utrecht-restores-historic-canal-made-into-motorway-in-1970s (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

MOHL, Raymond A. 2004. Stop the Road. Freeway Revolts in American Cities. Journal of Urban History, 30(5), pp. 674–706. doi: 10.1177/0096144204265180

STEHLIN, John. 2023. “Freeways without futures”. Urban Highway Removal in the United States and Spain as Socio-Ecological Fix? Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 7(3) [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486231215179 (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

SIEGELBAUM, Lewis H. (ed.). 2011. The Socialist Car: Automobility in the Eastern Bloc. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

KOUKALOVÁ, Martina et al. 2021. Prague Urban Planning. History of the Office of the Chief Architect of the City of Prague 1961–1994. Prague: The Prague Institute of Planning and Development, p. 76.

MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta et al. 2020. Bratislava (Un)planned City. Bratislava: Slovart, pp. 415–454.

Správa o koncepcii výstavby, rekonštrukcie a údržby cestnej siete vo Východoslovenskom kraji do roku 1970, 19 March 1966, zápisnice z rokovania predsedníctva, box 142, fund Východoslovenský krajský výbor Komunistickej strany Slovenska. State Archives in Košice (hereinafter ŠAvK [Štátny archív v Košiciach]).

Stanovisko ideologickej komisie a odboru výstavby a VSŽ k súčasným problémom architektúry vo Východoslovenskom kraji, 8 December 1964, zápisnice z rokovania predsedníctva, 1965, no. 1, box 132, fund Východoslovenský krajský výbor Komunistickej strany Slovenska. ŠAvK.

HALAGA, Ondrej R. 1992. Počiatky Košíc a zrod metropoly. Košice: Mesto Košice; OROSOVÁ, Martina and ŽAŽOVÁ, Henrieta. 2011. Košická citadela. Košice: Aupark.

DUCHOŇ, Jozef. 2004. Chunertov plán Košíc z roku 1807. Historica Carpatica, 35(1), pp. 103–116.

UNESCO. 2024. The Concept of the Lenticular Historical Town Core of Košice City. UNESCO World Heritage Convention: Tentative List, 1992–2024 [online]. Available at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1734/ (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

MIHÓKOVÁ, Mária. 1986. Výtvarný život a výstavba Košíc v rokoch 1848 – 1918. Košice: Štátna vedecká knižnica v Košiciach, pp. 117–203; LUKÁČOVÁ Elena and POHANIČOVÁ, Jana. 2008. Rozmanité 19. storočie. Architektúra na Slovensku od Hefeleho po Jurkoviča. Bratislava: Perfekt, pp. 101–106; História Košíc pre budúcnosť mesta: zásady ochrany pamiatkovej rezervácie. 2005. Košice: Krajský pamiatkový úrad v Košiciach; SEKAN, Ján. 2019. Urbanistické koncepcie a územné plánovanie v Košiciach 20. storočia. PhD thesis. Faculty of Architecture and Design, Slovak University of technology in Bratislava, pp. 11–58; PRIATKOVÁ, Adriana, SEKAN, Ján and TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2020. The Urban Planning of Košice and the Development of a 20th Century Avenue. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 54(1–2), pp. 71–88. doi: 10.31577/archandurb.2020.54.1-2.6

NĚMEC, Zdeněk. 1994. Košice 1780 – 1918. Sečovce: Pergamen, pp. 145–178.

Mihóková, M., 1986, pp. 143–147.

Sekan, J., 2019, pp. 94–101.

Zápisnica z príležitosti schvaľovacieho pokračovania návrhu územného plánu mesta Košice, 4 April 1952, box 48, fund Východoslovenský krajský národný výbor (hereinafter Vsl. KNV), odbor výstavy 1949 – 1960. ŠAvK.

Zápisnica z príležitosti schvaľovacieho pokračovania návrhu územného plánu mesta Košice, 4 April 1952, box 48, fund Vsl. KNV, odbor výstavy 1949 – 1960. ŠAvK.

Výhľad národohospodárskeho rozvoja mesta Košíc v navrhovaných etapách na obdobie 1965 – 1970, box 28, fund Magistrát mesta Košice 1954 – 1989 (hereinafter MMK), plánovací odbor, 1960. Košice City Archives (hereinafter AMK [Archív mesta Košice]).

GÓRKA, Adam and KUŠNÍROVÁ, Dana. 2021. Socialist Industrialization as a Factor of Urban Development and a Difficult Legacy in Košice, Slovakia. Architektúra a urbanizmus, 55(1–2), pp. 32–45. doi: 10.31577/archandurb.2021.55.1-2.3

Košice – Směrný územný plán města, no. 060/56SNA, box. 3, fund Ústredná správa bytovej a občianskej výstavby v Prahe 1956 – 1958. Slovak National Archives.

Košice – všeodborový dom ROH, box 66, fund Vsl. KNV, odbor výstavby a vodného hospodárstva 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prehľad o potrebe investičných kvót a finančných prostriedkov na zabezpečenie najnutnejších požiadaviek

rozvoja mesta v roku 1960, 5 February 1959, box 23, fund MMK, plánovací odbor. AMK.

Smerný územný plán mesta Košíc. Všeobecné závery a návrhy expertízy k smernému územnému plánu mesta Košíc, 10 August 1960, box 28, fund MMK, plánovací odbor. AMK.

Územný plán Košíc, no. 9, box 13, fund Vsl. KNV v Košiciach, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Územný plán mesta Košíc, no. 329/59, box 524, fund ONV Košice-vidiek 1954 – 1960. ŠAvK.

Podklady pre urýchlenú výstavbu osobného nádražia v rámci II. a III. časti výstavby železničného uzlu Košice, 1960, box 26, fund MMK, plánovací odbor, AMK; Rozvoj a výstavba mesta v rokoch 1960 – 1965, 26 April 1960, no. 151/60, box 28, fund MMK, plánovací odbor. AMK.

Prednádražie Košice, 1962, č. 15 – 30, box 17, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Predbežný návrh podrobného územného plánu prednádražného priestoru v Košiciach, 1962, box 10, fund Útvar hlavného architekta mesta Košíc. AMK.

SPURNÝ, Matěj. 2019. Věda a plán až do obýváku: městské plánovaní a proměna bydlení v Československu 1955 – 1980. In: Sommer, V. (ed.). Řídit socialismus jako firmu. Technokratické vládnutí v Československu, 1956–1989. Prague: Nakladatelství Lidové noviny, Ústav pro soudobé dějiny AV ČR, pp. 138–174.

Směrnice pro zpracování a náplň dopravní části směrných územních plánú, 1962, no. 118, box 17, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969, šk. 17. ŠAvK.

Závery a uznesenia Poradného zboru pre dopravné riešenie mesta Košice, 4–5 July 1963, no. 18, box 20, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Správa o činnosti Útvaru hlavného architekta pri zabezpečovaní úloh vyplývajúcich z hlavných úloh MsNV v roku 1967, jeho kádrové dobudovanie a riešenie otázky posilnenia útvaru komunistami, 6 June 1967, no. 127, box 31, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražie, 1965, no. 31 – 42, box 25, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražie, 1965, no. 31 – 42, box 25, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražie, 1965, no. 31 – 42, box 25, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražie, 1965, no. 31 – 42, box 25, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražie, 1965, no. 31 – 42, box 25, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražný priestor, 1966, no. 3, box 63, fund Vsl. KNV, odbor výstavby, 1960 – 1969, ŠAvK; Prestavba Gottwaldovej ulice, 1966, no. 108, box 77, fund Vsl. KNV, odbor výstavby, 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražný priestor, 1966, no. 3, box 63, fund Vsl. KNV, odbor výstavby, 1960 – 1969, ŠAvK; Prestavba Gottwaldovej ulice, 1966, no. 108, box 77, fund Vsl. KNV, odbor výstavby, 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Správa o projektovej a rozpočtovej dokumentácii na prestavbu Gottwaldovej ulice v Košiciach, 19 April 1968, Materiály rady MsNV 1968, fund MMK. AMK.

Informatívna správa o riešení optimálnych trás hlavných dopravných tepien mesta, Plánovací odbor MsNV pre Ministerstvo plánovania SSR, 15 October 1969, Prednádražný priestor. Prestavba Mlynského náhonu, 1966, fund MMK. AMK.

Prednádražie v Košiciach, 1965, no. Ra-1697/65, box 137, fund Sekretariát predsedu Vsl. KNV 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Záznam z večera otázok a odpovedí, 8 December 1965, no. Ra-2082/65, box 140, fund Sekretariát predsedu Vsl. KNV 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Prednádražie, 1965, no. 40, box 25, fund Vsl. KNV, komisia výstavby a odbor výstavby 1960 – 1969. ŠAvK.

Zápisnica o 192. schôdzke rady Mestského národného výboru v Košiciach, ktorá

sa konala dňa 11. júna 1971, no. 47, Rada MsNV Košice. AMK.

JANOVSKÝ, Jozef (ed.). 1975. Košice. Košice: Mestský národný výbor v Košiciach, p. 22.

Križovatka Hviezdoslavova – Marxova, 1. stavba, projektová úloha, 1976, box 33, fund Útvar hlavného architekta mesta Košíc. AMK.

Východoslovenské noviny. 1968. Zmeniť rozhodnutie MsNV. Východoslovenské noviny, 18 July 1968, (168); Východoslovenské noviny. 1968. Opäť o Mlynskom náhone. Východoslovenské noviny, 13 August 1968, (192).

Východoslovenské noviny, 23 November 1968, (281); Východoslovenské noviny, 17 December 1968, (301).

Večer, 16 May 1969, (92).

KLEBAN, Miroslav. 2024. Interview by Ondrej Ficeri, 5 August. Archive of Ondrej Ficeri.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2024.58.3-4.10

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License