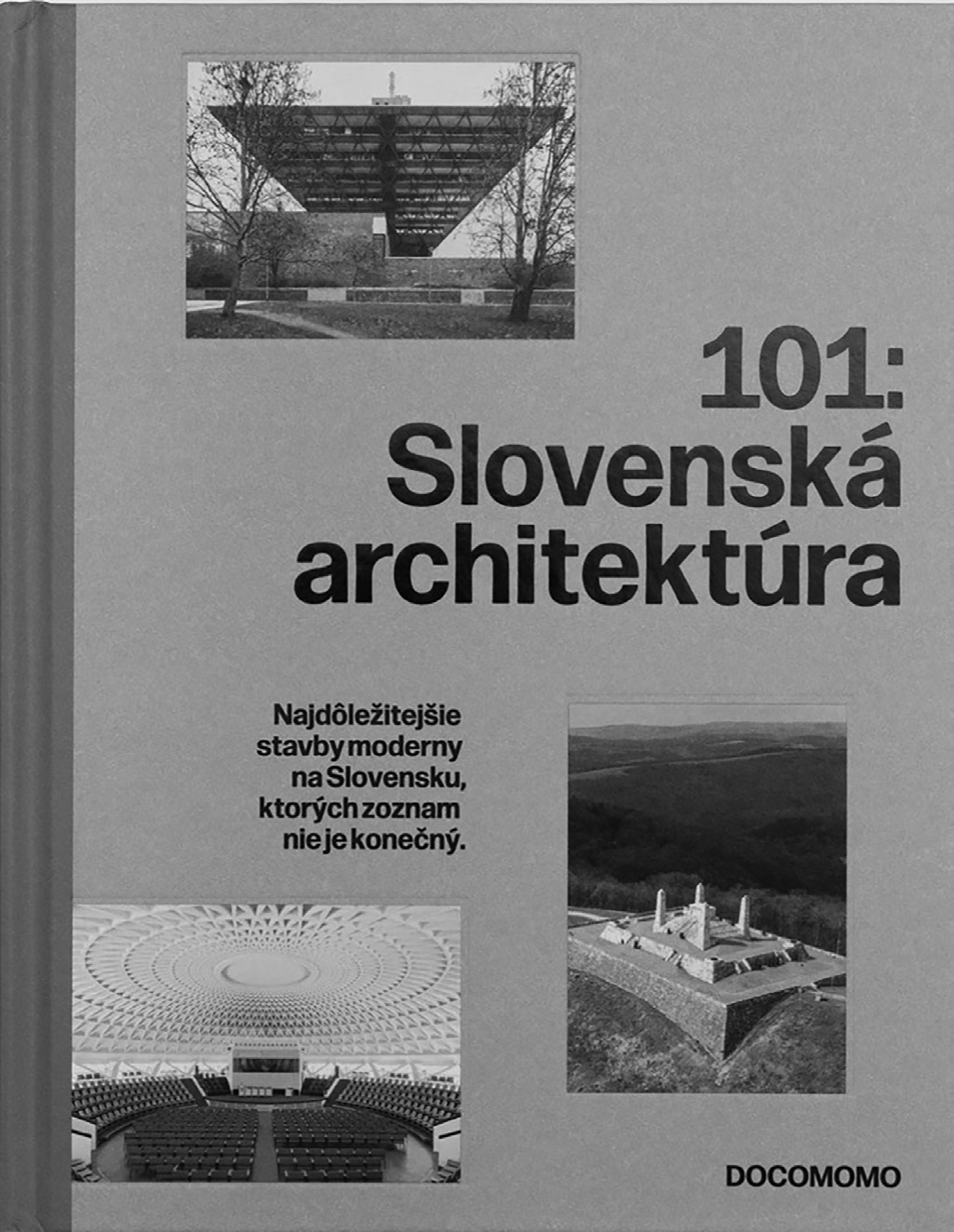

101: Slovak Architecture in the

DOCOMOMO register, 2024

Moravčíková, Henrieta,

Bočková, Monika,

Haberlandová, Katarína,

Krišteková, Laura,

Smetanová, Gabriela,

Szalay, Peter (eds.)

Bratislava: Čierne diery, o.z.

ISBN 978-80-69103-00-9

As of October 2024, the public has had the opportunity to read an exceptional seven-hundred-page publication entitled 101: Slovak Architecture, a volume that – as its title indicates – expertly summarises one hundred and one modern architectural works in Slovakia in the twentieth century. It is a response by members of the Slovak section of DOCOMOMO to an international initiative documenting and preserving buildings and urban ensembles of modern architecture. Selection of the works was shaped by experts from DOCOMOMO Slovakia with the members of DOCOMOMO International. The supplemented inventory of standing buildings was created ten years ago; however, no publication presenting this selection appeared until now.

To assume the challenge of summarising the results of research on dozens of buildings constructed during the complicated period of the twentieth century – which included the First Czechoslovak Republic, the wartime Slovak state, and the period of socialism – implies the need to make a choice on how to turn this idea into reality. The authors of the short texts in the book – Henrieta Moravčíková, Monika Bočková, Katarína Haberlandová, Laura Krišteková, Gabriela Smetanová and Peter Szalay – are all theorists and historians from the Department of Architecture at the Institute of History of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, hence the questions they answer are among the most current in international academic discourse. One immediate debate is over how to attract and retain the attention of the lay public; indeed, a question worth posing. After all, how many experts are there in Slovakia who work toward protecting buildings of modernity? If there were enough, and speaking with a strong voice, the building of the House of Trade Unions, Technology and Culture (known as “Istropolis”) by the architects Ferdinand Konček, Ilja Skoček and Ľubomir Titl, who received the Emil Belluš Prize in 2016, and the Považská Agrarian and Industrial Bank building, destroyed respectively in 2022 and 2016, could have been saved from demolition. At the very least, we can be thankful that both works have been given a place in the book. Although not all of the authors openly admit their intention as protecting other jewels of Modernism from possible demolition, this focus is nonetheless implicitly evident in this publication.

Other fundamental choices made by the authors include the use of both Slovak and English texts and the significant pictorial and photographic supplements. Unfortunately, the space occupied by these choices prevent them from more in-depth investigations for a professional audience in their texts. After all, how long would a book become if one hundred and one works were analysed in such textual detail?

Nonetheless, in terms of content, the publication is a groundbreaking event, not least in its use of language that speaks to the contemporary reader. Books examining architectural development in Slovakia in the twentieth century are still rare. To learn about individual eras or buildings from among the available literature, would require turning to publications from the past, often containing connections that, so to speak, bring forth the language of another time. One such case involves one of the most original works of post-war Modernism – the Memorial to the Slovak National Uprising in Banská Bystrica by the architect Dušan Kuzma1 with the sculpture “Victims’ Warning” by Jozef Jankovič. Even in the 1980s, in an article by Matúš Dulla, a expert still active at the Institute of History and Theory of Architecture and Monuments Restoration of the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Slovak University of Technology, the work was interpreted in the terms of the prescribed ideology, termed a significant example of socialist architectural creation and the starting point of a socialist tradition based on a deep artistic reinterpretation of historical tradition.2 By contrast, in the introduction to 101: Slovak Architecture, which carries the subtitle “Experiments of Modernism”, this monument is placed into a global historical context by Moravčíková, who also works at the Institute of History and Theory of Architecture and Monument Restoration, who terms it the strongest expression of Brutalism in Slovakia.3

The basic division of the chapters is chronological, following timelines and key periods. From this division, it can be assumed that the authors based their definition on the political and historical context. However, it is questionable whether such a division of chapters is relevant in architectural history, because in each chapter we find works that were designed in one of the timeline’s specific periods, yet were built later – and thus should, from the date of construction, belong to the following chapter. Nonetheless, the reader can see the introduction with the timeline before each chapter as a tool for clarity.

The timelines include key facts on the state of society, significant events in the architectural and artistic scene, and important works. The individual buildings in the chapters themselves take up about one to two written pages each, with the texts preceded by brief information on the design and construction of the works, the origins of the project and when (and if) the work became a national monument. The content of the texts includes descriptions and a focus on the uniqueness of the projects, background information relating to the architects, the inclusion of the works in the architect’s oeuvre, historical contexts and sometimes even nuances of style. Wherever necessary, the authors map and update the condition of the works. An English translation immediately follows the Slovak text. The individual articles include original black-and-white photographs of specific architecture as well as colour versions documenting their usually contemporary state, by the photographer Matej Hakár. No less worthy of praise is Michal Tornyai’s eye-catching graphic design, with the black-and-white images integrated into beige frames and the colour ones presented on separate pages against a white background. In doing so, he has given the reader a sense of lightness and airiness.

The first chapter is the richest in the quantity of works, spanning the period from the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the existence and demise of the First Czechoslovak Republic. Most of the buildings in this chapter were among the first to be included in the international DOCOMOMO register, but there are also more recent additions. The original list includes the Police Headquarters in Bratislava by the Czech architect František Krupka, the Mausoleum of General Milan Rastislav Štefánik by Dušan Jurkovič, and the Neolog Synagogue by the renowned German architect Peter Behrens; later additions include the Bratislava Synagogue by the architect Artur Szalantai and the Orthodox Synagogue and School in Košice by the architects Ludwig (Ľudovít) Oelschläger and Géza Boskó, among others. Alois Balán and Jiří Grossmann also receive a mention as the founders of the School of Arts and Crafts as the first public vocational art school in Slovakia preparing students for working life in art and industry.4 The selections in the chapter summarise the wide variety of modernist works by Slovak architects and indicate how strongly Czech, German and Jewish architects influenced the Slovak scene.

The second chapter looks at the period of the Second World War, when Czechoslovakia was broken up under pressure from Nazi Germany. Moravčíková writes in the introduction of the book (p. 18) that the authorities of the totalitarian regime of the Slovak state tried to formulate an idea of a specifically Slovak architecture: “It was to be inspired by history and national tradition. However, they could not define its form in any way. That is why modern architecture was popular in Slovakia in the 1940s.” The chapter concludes in 1947.

With the election victory of the Communist Party in the Czech lands after the Second World War, the Communists came to power throughout Czechoslovakia. This publication identifies an important impetus for the emergence of modern buildings at this historical juncture: the establishment of the Department of Architecture at the Slovak University of Technology in 1946, which became the independent Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering in 1951. At that time, the school was home to Emil Belluš and Vladimír Karfík, both prominent figures of Modernism, who in turn influenced several architects of the following generation, including Vladimír Dedeček, Kuzma, Ferdinand Milučký, Ivan Matušík and Ilja Skoček, who went on to create prominent Modernist works. Karfík already had experience of working in the United States, cooperating with Frank Lloyd Wright, and in France alongside Le Corbusier5 – an important point surprisingly absent from the book.

The following looks at the period starting in 1957 and ending in 1968 with the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops in August. Its first work is the College of Agriculture complex in Nitra by Dedeček and Rudolf Miňovský, described here as the most representative example of post-war Modernism (p. 477). The chapter includes the most famous creations of modern architecture such as the first crematorium in Slovakia by Milučký, inspired by Nordic architecture;6 the Memorial and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising in Banská Bystrica; the Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising in Bratislava; the inverted pyramid of Slovak Radio; and a lesser-known futuristic project for a primary school with a memorial in the small town of Nemecká (p. 562). The Ľudovít Fulla Gallery in Ružomberok and the Kamzík Television Tower, which were added to the DOCOMOMO international register in 2015, also appear in the chapter. Interestingly, the selection of works from the second half of the twentieth century does not differ from the selection made by the members of the Union of Slovak Architects in 1970 during the period of normalisation. At that time, the editors of the professional architecture periodical Projekt approached members and candidates of the union to name ten architectural works built in Slovakia after 1945 that they considered to be of undisputed and lasting value: Milučký’s crematorium came first, the College of Agriculture in Nitra was second, Matušík’s Prior Department Store was third, and the Memorial to the Slovak National Uprising in Banská Bystrica was fourth.7

The selection of works of modern architecture in Slovakia ends in 1988, the year before the Velvet Revolution. From then on, the reader only has an austere table with basic information about events connected with architecture and architectural works up to the present day.

In documenting modern buildings constructed in the twentieth century, the authors rely on the results of research at the Department of Architecture at the Institute of History of the Slovak Academy of Sciences and the Institute of History and Theory of Architecture and Monument Restoration of the Faculty of Architecture and Design at the Slovak University of Technology. Considering the publication’s scope and length, the necessary emphasis on brevity and conciseness, or the occasional overgeneralisation of ideas in the texts of the publication, does not allow room for annotation. Further information appears only in the introduction by Moravčíková, which presents the structure of the book in individual periods. Nevertheless, the publication is an excellent source of information. It can become a fundamental guide to the development of modern architecture in Slovakia for anyone familiar with twentieth-century architecture, be they theorists, historians, students of architecture or simply anyone interested in architectural events.

Moreover, the individual entries can provide suggestions for deeper and more extensive academic research. Examining the omitted and unmentioned works and their possible modernity could enrich and deepen the selection of works in future efforts. One debate that is still relevant today is the question of further selection. Will future works in the DOCOMOMO register include the extension of the Slovak National Gallery by Dedeček or the new Matica slovenská building and the Slovak National Library building by Kuzma and his team? Will works of postmodernism ever become part of the register?

1 Dušan Kuzma (1927–2008) was one of the first graduates of the Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering of the Slovak University of Technology (1952). In 1960, he founded and headed the Department of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava.

2 DULLA, Matúš and ZALČÍK, Tibor. 1982. Historical Traditions in Socialist Architecture. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 16(2), p. 106.

3 MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta. 2024. In the Service of Modernisation, Emancipation and Politics: 101 Works of 20th Century Architecture in Slovakia. In: Moravčíková, H. et al. 101: Slovak architecture. Bratislava: Čierne diery, o.z., p. 19.

4 NAGYOVÁ, Linda. 2023. One Step Further in Researching the ‘Bratislava Bauhaus’. Profil – Contemporary Art Magazine, (1), pp. 154–158.

5 NOVÝ, Otakar. 1994. Vladimír Karfík – Architect of the 20th Century. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 28(4), pp. 235–246.

6 DULLA, Matúš. 1997. Crematorium and Urn Grove. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 31(3), p. 35.

7 Projekt. 1970. Survey of the Union of Slovak Architects. Projekt, (3), pp. 100–101.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License