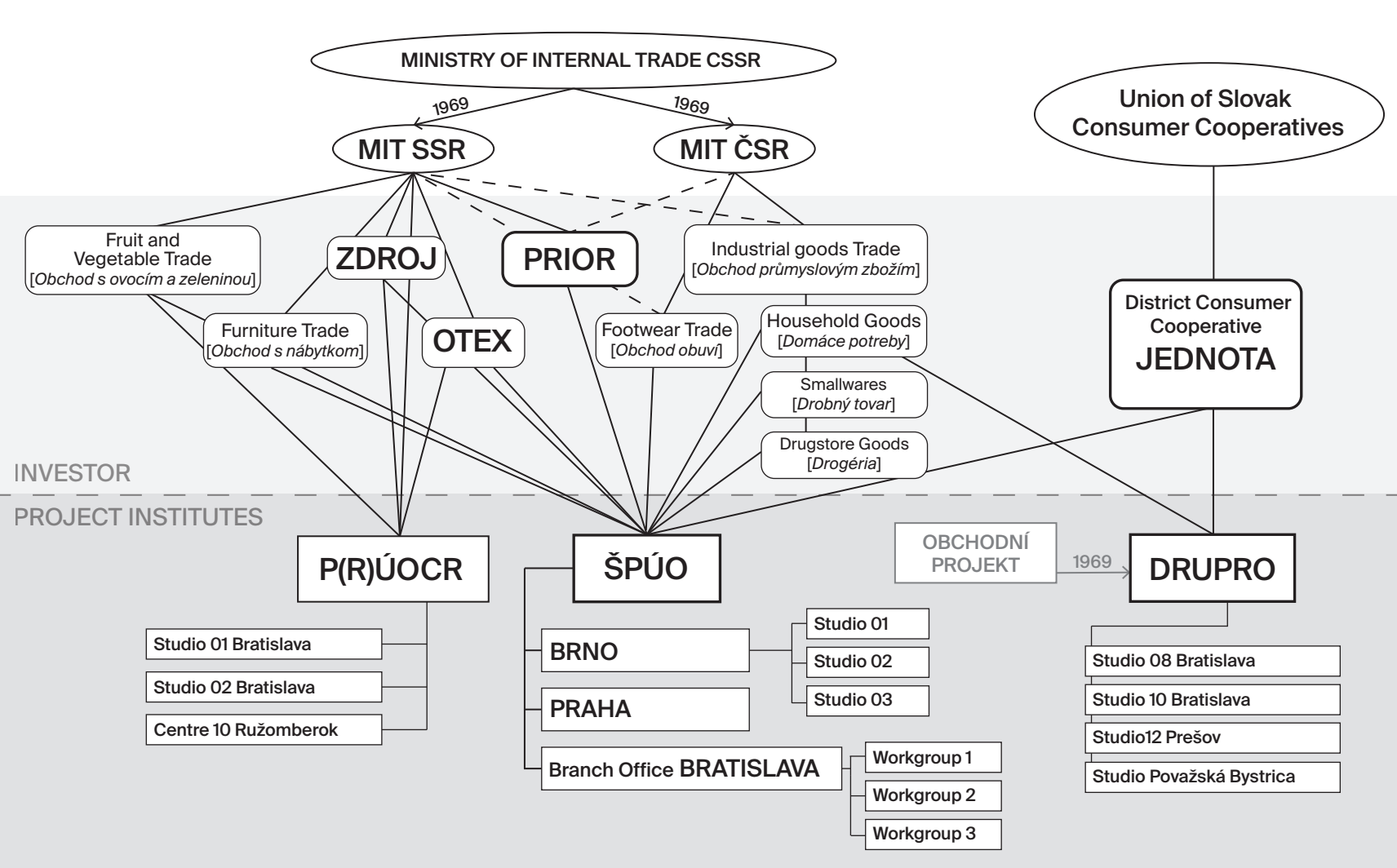

The study examines the mechanisms behind the postwar development of department stores in (Czecho-) Slovakia against the background of the centrally planned economy of the socialist state. It examines the role of both state (Prior) and cooperative (Jednota) enterprises, along with specialized state owned project institutes like ŠPÚO and DRUPRO, in shaping this typology. Emphasizing rationalization, standardization, yet equally architectural innovation, the text reveals how department stores became tools of modernization, socio-political representation, and urban development – yet today face neglect or demolition despite their cultural and architectural significance.

Department stores represent both a specific building type and a socio-cultural phenomenon that significantly reshaped centers of Slovak cities in the second half of the twentieth century, simultaneously reflecting the transformation of (Czecho-) Slovak society towards a Western, consumerist way of life. Though originating in an environment of centralized control over all aspects of the economy – from investor to contractor – they also offered architects opportunities to explore new artistic, structural, and operational solutions. Despite its historical and aesthetic significance, this architectural typology has begun to disappear from the Slovak urban landscape almost as quickly as it began first appeared starting in the 1960s. Many buildings are undergoing radical reconstruction or are being demolished and replaced with new shopping center architecture.

This study summarizes the development of the department store network in Slovakia in the post-war period and examines the issues surrounding their planning and construction within the specific conditions of a centralized command economy and the organization of state architectural institutions. On the other hand, the intention is not to analyze the architectural form of these buildings or its transformation over time, but rather to discern the specifics of the state-planned construction of the department store network in socialist Czechoslovakia and the factors that shaped its development and final form. And equally, to inquire as to how Slovak department-store production differed from its Czech equivalent.

The typology of department stores is a rarely explored topic in current Slovak architectural historiography. Significant attention has only been given to the Prior department-store complex on Kamenné Square in Bratislava1 and the Prior department store in Košice.2 These buildings were the two examples used in the discussion of the architectural value of department stores in relation to the socialist regime by Natália Kvítková.3 In the book published by the Czech National Heritage Institute, Obchodní dům Prior / Kotva, among the selected examples of Czechoslovak department stores, only the Jednota store in Trnava is included alongside the Priors in Bratislava and Košice.4 Several department stores in which architect Ivan Matušík participated are featured in his monograph,5 and notes on individual Prior department stores are found in a study by Matúš Bišťan on the INTEGRO structural system.6 While specific department stores are mentioned general publications on 20th-century Slovak architecture,7 the most comprehensive treatment to date of the topic of department store construction in Slovakia can paradoxically only be found in the Czech publication Kotvy Máje.8

In the Czech context, numerous contributions to the topic have emerged in recent decades.9 In the professional discourse there, the term “Priorization” has spread to describe the phenomenon of department store architecture permeating Czechoslovak towns; referring to the state department store network Prior, it originally had a pejorative connotation.10 However, since the present study’s goal is a comprehensive picture of the planning and construction of the Slovak department store network in the post-war period, its scope should also include the construction activities of the cooperative retail network under the brand Jednota, which played a considerable role in its development.

The study draws on period texts from specialized literature, company brochures, and articles published in professional architectural journals such as Projekt, Architektura ČSSR, Československý architekt, as well as trade-focused journals like Socialistický obchod [Socialist Commerce]. Additional sources for analysis include methodological guides and research reports issued by the Research Institute of Trade, archival materials from design organizations and retail corporations (limited to fragments of the archives of Brno’s SPÚO, Bratislava’s PRÚOCR, and the Prior headquarters archive),11 and records from interviews with living architects from SPÚO (Jan Melichar, František Kalesný, Andrej Gürtler) and DRUPRO (Lumír Lýsek, Lýdia Titlová).

Department Stores as a Political Issue

“From the capitalists, we inherited primarily small, inadequately equipped, and unhygienic retail units. It was necessary to reorient the material-technical base through concentration and rationalization, while also ensuring the dynamic growth of retail turnover.”12

The socialist press often portrayed the state of the retail network in interwar Czechoslovakia as inadequate, indicating the previous capitalist regime as responsible for the situation in which commerce still found itself in the early 1960s. Although the typology of the department store appeared relatively late in Czechoslovakia during the interwar period, the realizations often were of exceptional architectural merit.13 However, their concentration in larger cities resulted in an uneven distribution of the retail network across the country. In Slovakia, they appeared in greater numbers only in the capital city, with a few other examples, most notably the department stores run by the Baťa shoe company or private entrepreneurs, found in Žilina, Trnava, Košice, or Partizánske (before 1949 the Baťa manufacturing town of Baťovany).14 A more significant factor in the unfavorable state of the department store network was the near-complete halt in their development during the 1940s and 1950s: the result of the nationalization of all existing department stores and commercial enterprises in 1948, coupled with the centralized economy’s lack of interest in the consumer sector during the first years after the regime change.15 Since economic plans initially focused on heavy industry and state construction prioritized housing development, the few projects related to building a retail network were sporadic and served mostly immediate, often emergency needs.16

“The constantly decreasing size of retail spaces, minimal investment in the renovation of old stores, and less-than-ideal retail policies in new housing estates caused the development of the retail network to become a serious political issue.”17

However, the gradual rise in the population’s standard of living and the development of the economy – contrasting with the unsatisfactory state of the retail network – forced the state to begin addressing the development of the retail sector. More significant changes occurred in the 1960s with attempts to reform the system. The fourth Five-Year Plan called for “the gradual reconstruction and modernization of processing industries, especially the consumer goods and food industries.”18 In 1968, retail was assigned high “economic and political importance,” and the Ministry of Internal Trade launched an extensive investment program for the construction of the retail network, with department stores expected to take on a “substantially more significant role” in new development.19 Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the establishment of the retail sector’s material-technical base [materiálno-technická základňa] repeatedly became a focus of the ruling party and an integral part of its five-year economic plans, reflected among other areas in the intensive development and construction of department stores. The regime began using trade buildings to demonstrate its ability to meet the needs of the population, to showcase its material achievements, and to underline its ownership of the means of production.

- Department stores and shopping centers have become a kind of three-dimensional poster for the rising standard of living in socialist countries. They are learning the difficult art of satisfying the various needs of the general public as well as the growing demands for quality and beauty. They have become architectural adornments of our settlements.20

- Department stores must be the showcase of our time; they must set the right direction for other retail systems in terms of appearance, technical equipment, and operation, and they must turn shopping into a pleasurable experience for the customer.21

Department stores, as the largest, most complex, and architecturally most prominent buildings, became the flagship structures of retail construction. Simultaneously, in both large and small towns, they demonstrated the modernizing ethos of the socialist regime. This was also tied to the development of this building typology in neighboring countries. The rivalry with the “Western world” brought about the need to match department stores and shopping centers on the other side of the Iron Curtain, as well as those in other socialist bloc countries.22 A certain “schizophrenia” inherent in this development – where Western consumer society was ideologically rejected, yet consumption was actively promoted by the state – has already been observed by several authors.23

In addition, department stores became an important tool in the gradual, state-driven urbanization of the country. The development of the retail network became the subject of methodological manuals issued by the Research Institute of Trade [Výskumný ústav obchodu – VÚO], where guidelines were strictly defined based on settlement size and calculated catchment areas.24 As early as 1958, the VÚO issued a directive stating that every settlement with more than 30,000 inhabitants, with an appropriate catchment area and purchasing power, was to have a department store built.25 As part of what became known as central commercial infrastructure, department stores were constructed not only in the centers of district towns but also as integral parts of comprehensive housing developments in housing estates and industrial centers.

The Department Store as a Building Type

The department store was defined as the most progressive form of retail network development in Czechoslovakia, and the largest and most concentrated retail unit in terms of sales area and turnover. A department store consisted of a group of specialized departments offering goods for basic, frequent, and long-term needs, all concentrated in a single building with its own administrative apparatus. Although department stores originally developed in connection with the booming textile industry during the 19th century, in the postwar period they came to include grocery sections and a wide range of additional customer services, such as restaurants and snack bars, tailoring services, shoe repair, children’s play corners, and many others. The core idea was to maximize the range of goods offered and to sell them under a single brand and “under one roof” on a single open retail floor, using “progressive sales techniques” like self-service and open selection.26

Postwar department stores were classified as: Full-assortment stores (selling a complete range of food and non-food items), Broad-assortment stores (smaller department stores of consumer cooperatives) and Specialized stores (fashion house, furniture house, food house, shoe house, etc.). Starting in the 1970s, a new type emerged: the Combined Department Store [Združený obchodný dom – ZOD] or Combined Shopping Center [Združené nákupné stredisko – ZNS], which, unlike traditional department stores, had multiple investors operating simultaneously on different floors or in separate sections of the building.27

The size of a department store was determined by the size of the town and its designated catchment area, generally ranging from 2,500 to 12,000 m². As part of the so-called “higher” and “central retail infrastructure,” they were typically built in towns with over 25,000 inhabitants, and only rarely as part of local-level infrastructure or satellite shopping centers.28 Layouts were designed to support flexibility of store operation. Unlike other types of retail establishments, where standardization was widely used, department stores were highly individualized in both their architectural and artistic design.

Investment activity and construction in retail were governed by “technical-economic indicators” [technicko-hospodárske ukazovatele – THU] – absolute and relative values that qualitatively described retail operations. These indicators (related to sales and storage area, turnover, investment costs, product range, etc.) were established based on data from already completed projects and their evaluations.29

The PRIOR Department Stores

In line with the concept of the centrally managed economy, all extant department stores were expropriated in 1948 and merged into the newly created enterprises Obchodní domy [Department Stores] in the Czech lands and Slovenské obchodné domy in Slovakia. In 1954, an independent Main Administration of Department Stores was established with nationwide authority; Slovak department stores, it should be noted, were separated from this administration in 1957 and placed under the Main Administration of Industrial Goods Trade. From 1960, department stores throughout the country were managed by the Textile Trade Association.30

Finally, in 1965, the organization stabilized with the founding of the conjoined national enterprise Obchodné domy, which unified all former department store enterprises in Czechoslovakia under a single management. The General Directorate in Bratislava was headed by Štefan Hanakovič, later succeeded by Adam Makula, and it was the only general directorate of a state enterprise in the ČSSR to be situated in Slovakia. On 1 January 1968, the enterprise adopted a new name and brand: PRIOR Department Stores, a change justified by the need for a unified commercial policy and brand promotion. During its years of operation, the enterprise created a strong commercial and visual identity, well known to several generations of Czechoslovak citizens.

Organizationally, the company was divided into 20 branches, each managing additional sub-branches: the 55 department stores across Czechoslovakia that came under the enterprise’s control in 1965. However, only 19 of them had the full characteristics of a department store, and only Bílá labuť (completed 1939) in Prague offered a complete product assortment. In most cases, these structures were retail units built during the interwar period, more than half of which had a sales area of less than 1,000 m².31

In 1969, the organizational structure was reconfigured in the form of a trust of enterprises made up of the former branch plants. Due to the rapid development of new units, the structure had to be reorganized shortly thereafter. By 1979, the organization stabilized on a regionally structured system, with 11 Prior department store enterprises across all regions of the ČSSR (excluding the Central Bohemian region). On the Slovak side, these were the Western Slovak, Central Slovak, and Eastern Slovak Prior department stores. The trust also included an import-export company and the Dona Prostějov mail-order department store.32

Cooperative Trade and the

Jednota Consumer Cooperatives

In Czechoslovakia, the operation of domestic trade was ensured not only by the state but also, in almost one-third of total volume, by cooperative trade (the ratio between state and cooperative trade being 70.5:29.5).33 While Prior department stores represented state trade, consumer cooperatives developed a retail network under the brand Jednota [Unity]. District-level consumer cooperatives were formed through the authoritarian unification of all existing food cooperatives after 1948 and gradually took over private retail stores. At the national level, they were managed by the Union of Slovak Consumer Cooperatives, which operated under the Central Council of Cooperatives.

From 1952, as part of the so-called “rajonization” process, consumer cooperatives were restricted to operations exclusively in rural areas and small towns, resulting in the mutual exchange of retail units between the state and cooperative sectors. Hence, state trade gained a monopoly in cities, while consumer cooperatives dominated the countryside. Only after the abolition of this regulation in 1967 were cooperatives allowed to focus on the construction of shopping centers and department stores in urban areas.34 During the 1970s, and even more in the 1980s, the number of cooperative department stores and shopping centers significantly increased, whether in terms of quantity, retail area, or turnover. Between 1963 and 1983, the number of department stores rose from 13 to 40, while the number of shopping centers increased from 2 to 189 in the same period.

Development of the Department Store Network in Slovakia

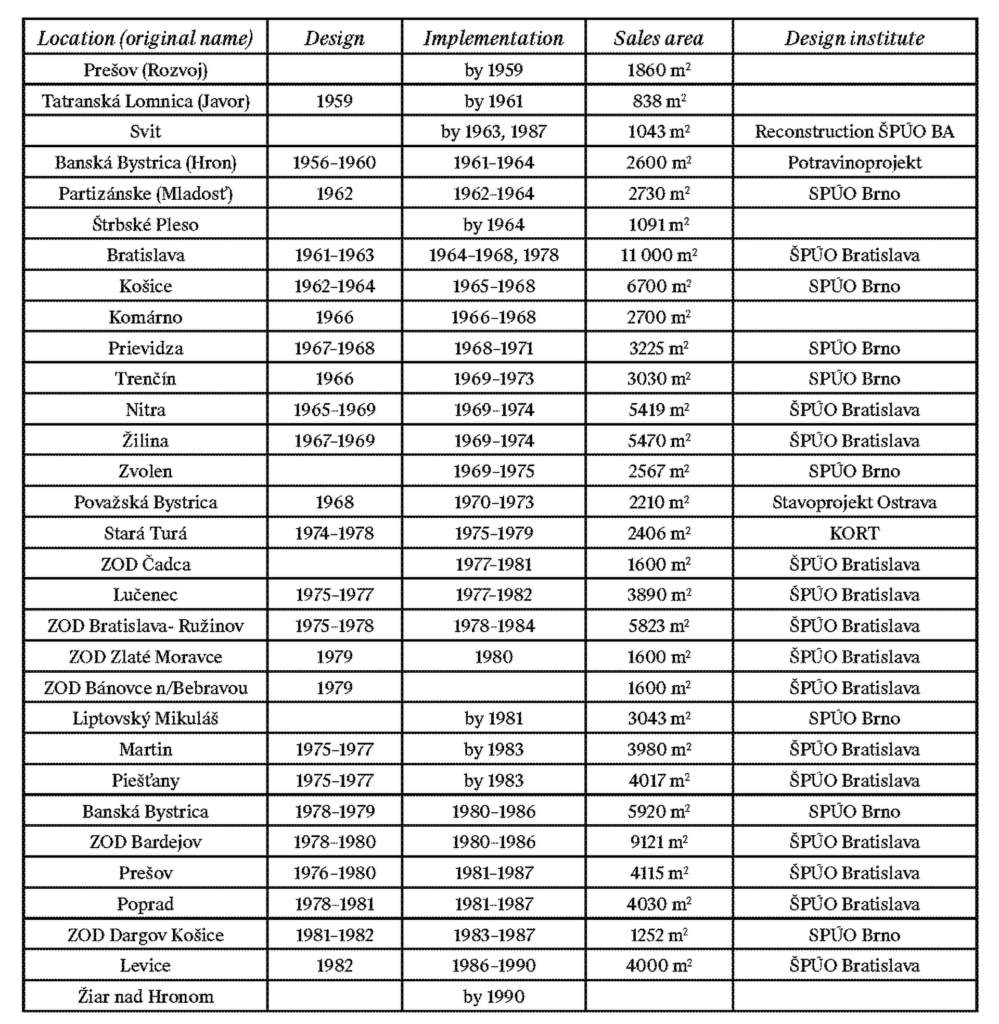

Although the rise of department stores in Czechoslovakia is usually associated with the late 1960s and early 1970s, new construction, albeit uncoordinated, had already begun in the 1950s. The sales area of these early department stores usually did not exceed 3,000 m² (often not even 1,000 m²), and they did not meet the requirements for full-range sales35. At the end of 1959, the Rozkvet [Flourishing] department store was opened in Prešov, followed by Javor [Maple] in Tatranská Lomnica in 1963, Mladosť [Youth] in Partizánske in 1964, and Hron in Banská Bystrica. Smaller department stores with sales areas under 1,000 m² were opened in Trnava (1964), Trebišov (1965), and Poprad (1966).

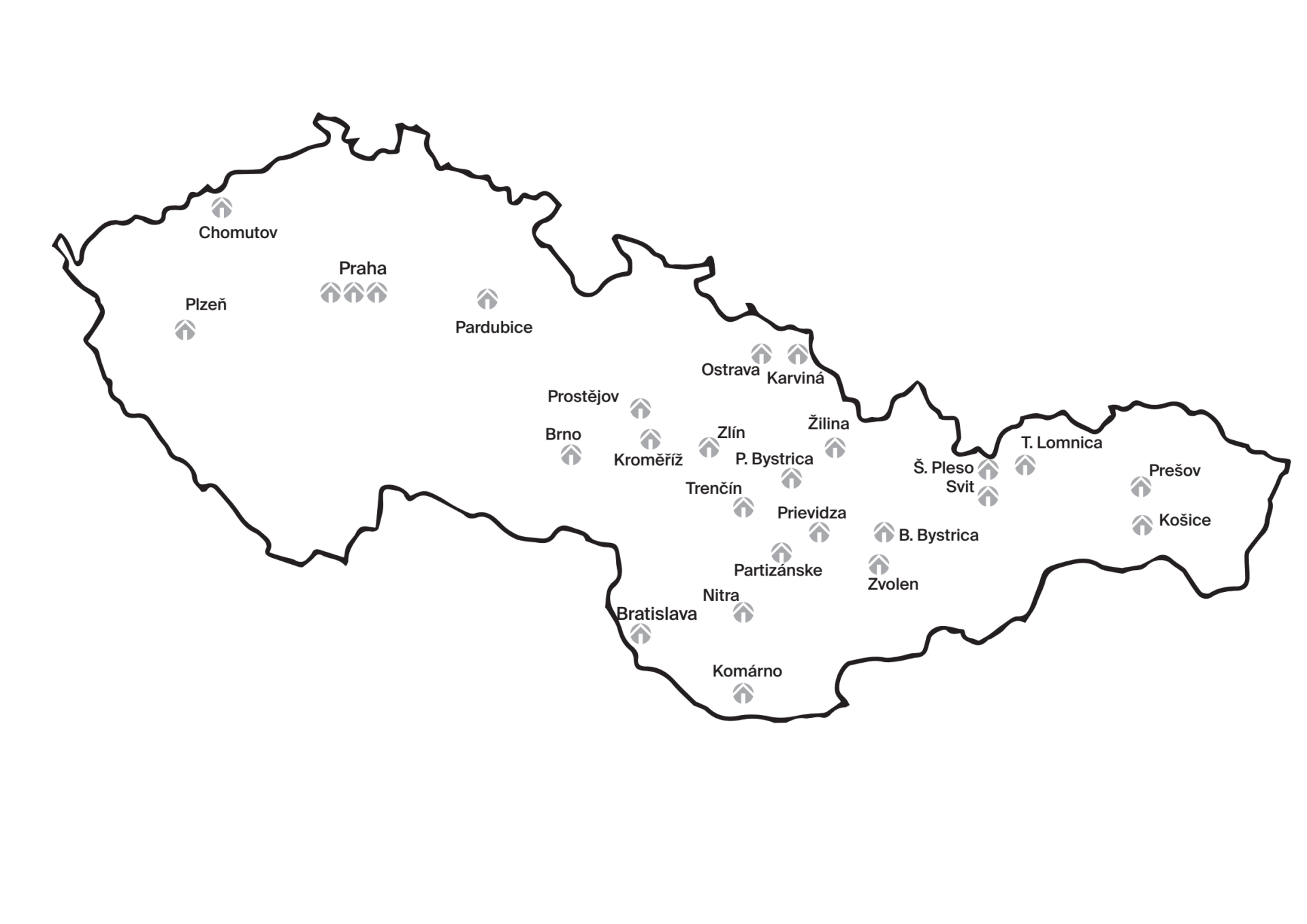

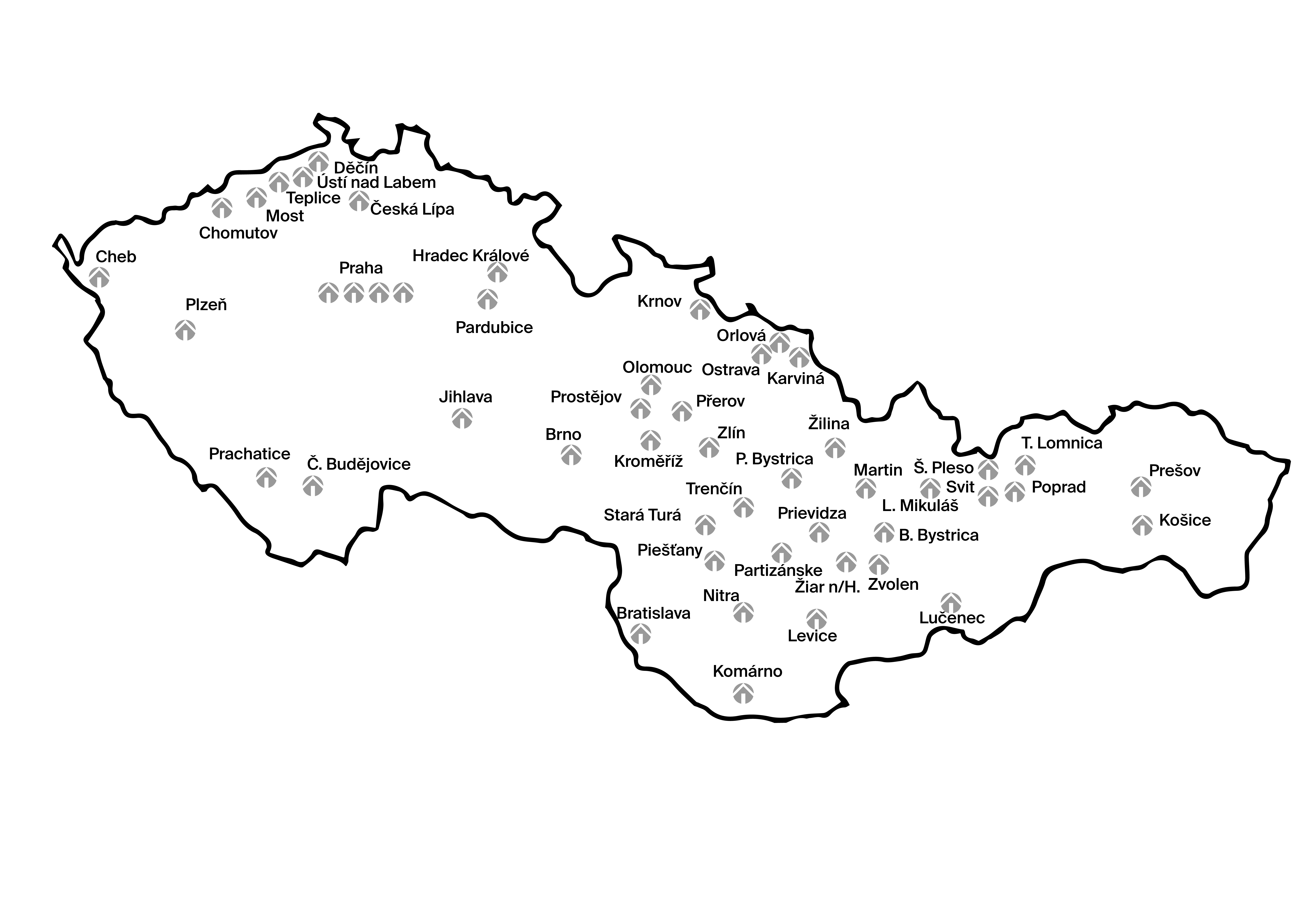

Shortly after its establishment, the state enterprise Obchodné domy formulated a long-term concept for department-store construction up through 1980, approved by the Ministry of Trade of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1967. Across the country, the plan included the initiation of 19 new units by 1975 and another 15 by 1980. At the time the concept was adopted, three department stores were already under construction in Slovakia, all opening in 1968 – two substantial projects in Bratislava and Košice, and a smaller one in Komárno. In the first phase (by 1975), the plan included new department stores in Prievidza, Trenčín, Považská Bystrica, Zvolen, Nitra, Žilina, Trnava, Nové Zámky, and the completion of a connecting building in Bratislava. The high success rate (with all planned stores completed except Trnava and Nové Zámky, where Jednota eventually built the department stores, while the connecting building in Bratislava was completed in 1978) reflected the intense efforts to expand the department store network at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s.

In the second phase (until 1980), department stores were planned for Martin, Ružomberok, Liptovský Mikuláš, and Piešťany. Following the federalization of the Czechoslovak state, a separate Concept for the Construction of Prior Department Stores in Slovakia until 1980 was created in 1972. This plan expanded the list of target locations to include Bratislava-West, Bratislava-Ružinov, Bratislava-Petržalka, Košice II, Poprad, Prešov, Lučenec, and Banská Bystrica. Additional plans involved department stores in Levice, Čadca, Malacky, Spišská Nová Ves, Púchov, Trebišov, Šaľa/Galanta, Žiar nad Hronom, Humenné, and Bardejov.36 This ambitious plan, however, was less successful than the first phase. Some of the projects were completed during the 1980s (e.g., Lučenec, Liptovský Mikuláš, Prešov, Poprad, or Levice); in other locations, joint investment department stores (not in the Prior network) were developed by the Ministry of Trade: Bratislava-Ružinov, Košice, Čadca, Zlaté Moravce, Bánovce nad Bebravou, Prievidza, and Bardejov. In several towns, it was consumer cooperatives that built department stores instead, e.g., in Ružomberok, Malacky, Spišská Nová Ves, Šaľa, or Humenné.

Additionally, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Jednota department stores became integral parts of town centers in many district capitals (e.g., Brezno, Nové Mesto nad Váhom, Rožňava, Senica, Snina, Topoľčany, Turčianske Teplice and others) and additional locations (Giraltovce, Sereď, Handlová, Šamorín, Bratislava-Krasňany, etc.). Parallel to this, department stores from other Ministry of Trade enterprises were also built (e.g., the Dom Odievania [House of Clothing] in Bratislava or Šíravan in Michalovce, both funded by OTEX), and others emerged as part of the process termed “complex housing development” – i.e., the provision of public infrastructure for newly built housing estates (e.g., Prior in Stará Turá, or the Jednota stores in Nitra and Prešov).

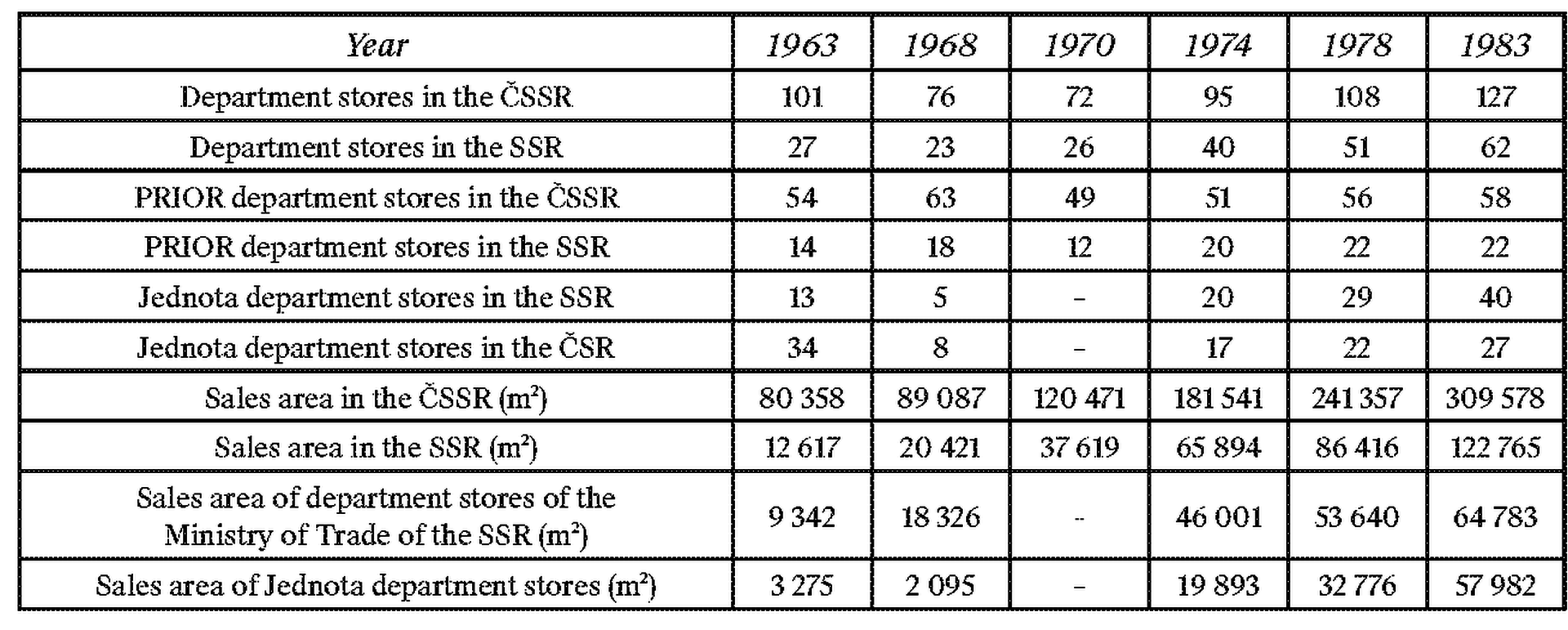

The development of the retail sector’s material-technical base [materiálno-technická základňa maloobchodu] was carefully monitored and evaluated using metrics such as the number of stores, total retail area, and retail turnover. This planning requirement was mainly fulfilled by the Trade Research Institute, though individual enterprises also maintained their own statistics.37 These clearly show that, initially, the number of department stores slightly declined due to the closure of older units. However, starting in the 1970s, there was a significant and relatively steady increase in both the number of buildings and sales area. Political efforts to expand the department-store network were thus reflected in real developments.

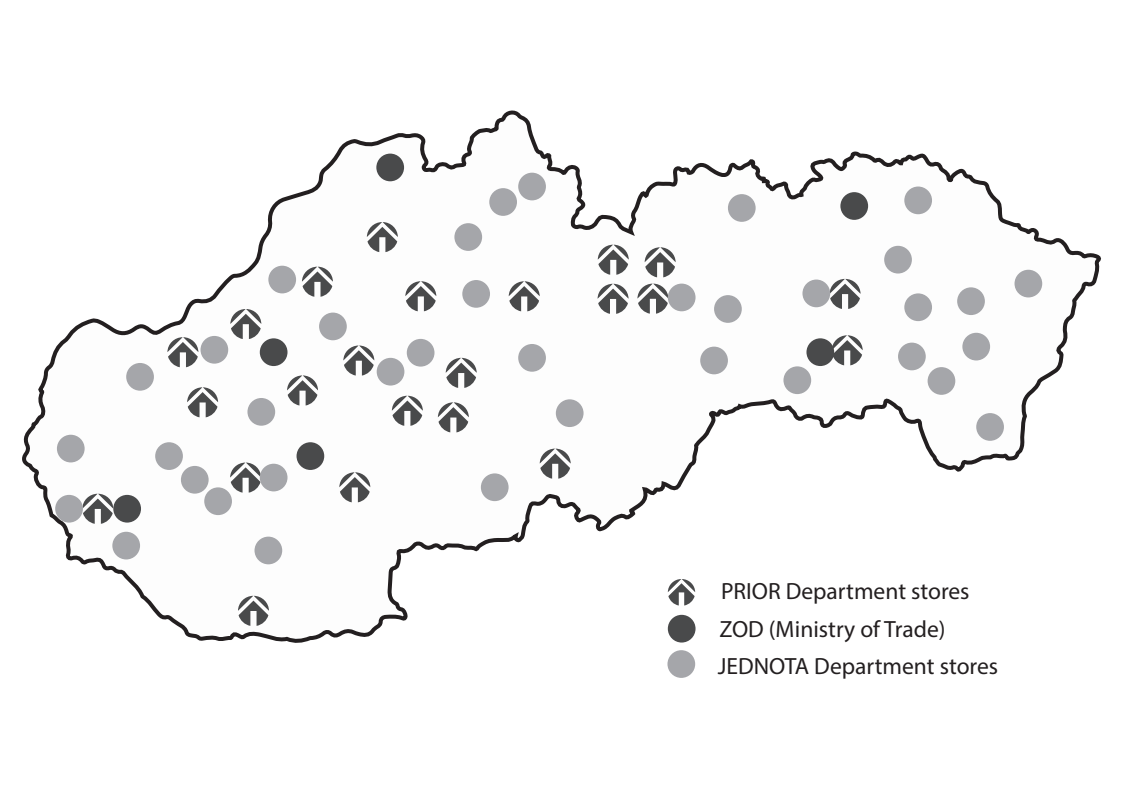

In total, between 1968 and 1990, 19 new Prior department stores and more than 40 Jednota department stores were built in Slovakia. For comparison, in the Czech lands during the same period, about 25 Prior department stores and up to 40 cooperative department stores were completed. Proportionally to the area of each country, Slovakia experienced significantly more intensive growth in both retail systems. In the Czech lands, the number of cooperative department stores even fell from 34 to 27 between 1963 and 1983.38 A key factor here was the restriction of cooperative trade to rural areas, which in the Czech part of the country lasted until the end of the 1980s.39 However, a graphic representation of the data clearly shows that the Prior network covered a large portion of Slovak territory – especially in the western and central regions. In contrast, in eastern Slovakia and other peripheral regions, Jednota department stores had a stronger presence.

To rationalize and increase the efficiency of both operation and construction, the “Unified Organization of Management and Operation of Prior Department Stores” [Jednotná organizácia riadenia a prevádzky obchodných domov Prior – JORP] was issued in 1972. Based on insights and experience gained from the construction of the first Prior department stores, as well as impulses from abroad, it did not explicitly focus on the architectural aspects of department stores, though addressing specific operational elements that directly influenced architectural design. The document defined the product assortment and its division into sectors, the turnover structure, the distribution of merchandise across sales floors, sales techniques, the range of services and auxiliary functions offered, as well as the movement of goods, customers, and employees. Each of the presented standards were categorized as mandatory, optimal, and recommended. Various indicators were applied to three different size categories of department stores based on their sales area: Small (2,000–4,000 m²), Medium (4,000–7,000 m²) and Large (7,000–10,000 m²).40 Between 1972 and 1981, the JORP program was implemented in 30 Prior department stores, accounting for more than 70% of the total sales area of the network. The system was later updated in 1988 in the form of the “Operational and Assortment Typology of Full-Range Department Stores.”41

Mechanisms of Centralized Planning of Department Stores

In post-war Czechoslovakia, department stores emerged as the result of close cooperation between several state-controlled entities. Alongside Prior, OTEX, or Jednota in the role of investor, the construction of these buildings would not have been possible without a contractor – typically (though not exclusively) represented by the regional state construction company Civil Buildings [Pozemné stavby] and a designer, usually affiliated with a designated state project institute. The establishment of state planning institutes was one of the outcomes of nationalization and the centralization of economic management in Czechoslovakia after 1948, following the Soviet model.42 During this process, the construction industry was nationalized, and specialized design departments were gradually created, employing nearly all the state’s qualified architects. After the founding of regional project institutes known as Stavoprojekt, which were responsible for housing and civic construction within their regions, the socialist design sector expanded in the 1950s with the creation of specialized institutes for various ministries and cooperatives.43 These sector-specific project institutes often focused on unique operational needs and atypical projects, where standardization played a much smaller role than in the work of Stavoprojekt architects. A distinct category included project organizations serving non-industrial sectors, such as the State Project Institute of Trade, the Project Institute of the Ministry of Culture, Zdravoprojekt (Ministry of Health), or Spojprojekt (Ministry of Transport). These institutes were dominated by architects who specialized in a narrow field of architecture and thus had a significant influence on the development trends within their specific domain.44

Initially, the design of the retail network was understood as a regular part of civic infrastructure, and individual projects were developed within various departments without any specific focus on the needs of trade architecture. The demand for specialized design departments led to the establishment of three institutes that played a key role in the construction of department stores in Slovakia: State Project Institute of Trade [Štátny projektový ústav obchodu – ŠPÚO], Project (and Rationalization) Institute of Trade and Tourism [Projektový (a racionalizačný) ústav obchodu a cestovného ruchu – PRÚOCR] and Cooperative Project Institute [Družstevný ústav pre projekciu – DRUPRO].45

The State Project Institute of Trade (ŠPÚO)

In 1953, the State Project Institute for the Design of Buildings for the Food Industry, Purchasing and Trade, known as Potravinoprojekt, was established under the Ministry of the Food Industry.46 Its task was primarily the design of architecturally simple industrial facilities for food processing plants (dairies, canneries, packaging and machinery plants, etc.), but also buildings for domestic trade and the purchase of goods. Over time, various departments were separated from the original organization according to their specific focus, including the relevant employees.47

In 1960, by separating six relevant design studios, an independent design institute was created under the Ministry of Internal Trade – the State Project Institute of Trade (ŠPÚO). The new institute was responsible for the design of wholesale warehouses, department stores and retail shops, as well as for structures related to tourism and a wide spectrum of construction tasks connected with trade, such as silos, packing facilities, food processing and semi-finished product plants, factories for refrigeration equipment, and kitchen technology systems.48

The ŠPÚO headquarters, with three studios (01, 02, 03), was based in Brno, where other departments were also located—such as the Engineering Services Studio 08, the Surveying and Geodesy Studio 09, and later the Studio for Rationalization and Informatics. In Prague, a separate Studio 10 operated.49 In 1961, a branch was established in Bratislava, and in 1989, a short-lived Studio 8000 was formed in České Budějovice.50

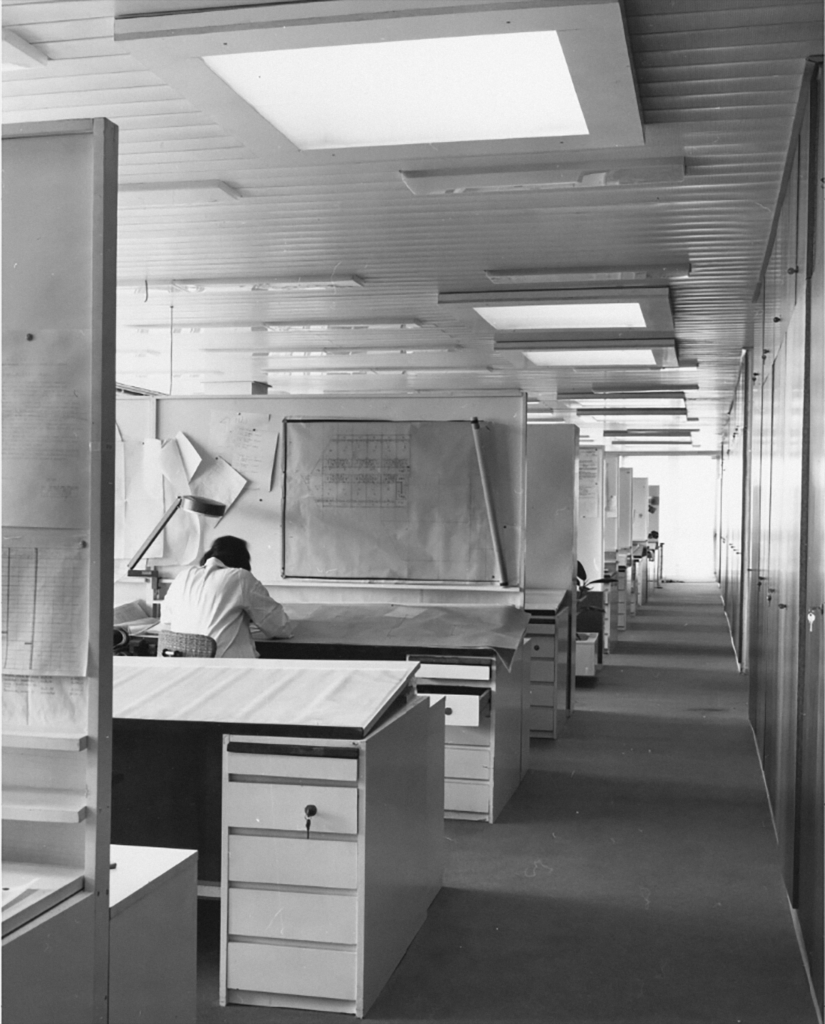

Architect Jaromír Sirotek led the institute for the first ten years, but in 1970 was removed from office for political reasons and replaced by the regime-aligned architect Zdeněk Jiřička. Nonetheless, the true architectural leader was Zdeněk Řihák, head of Studio 01.51 While his studio focused mainly on the design of tourism and dining facilities, department stores and shops were primarily handled by Studio 02, first led by architect Jaroslav Hlavsa, later by Alois Semela and Bohumil Merta. Studio 03, focused on the design of warehouses and logistics facilities, was led by Ladislav Novák, later by Stanislav Kubík.52 Designing buildings for trade was not an individual effort: each center operated with several mutually interacting teams, composed of a wide range of specialized designers focusing on trade and warehouse logistics, as well as various technical professions: structural engineers, HVAC experts, specialists in sanitary installations, cooling, heating, communication systems, fire protection, and more. Notable contributors to the design of department stores and other commercial buildings at ŠPÚO included Růžena Žertová, Jan Melichar, Josef Opatřil, Josef Pálka, and František Antl. Other well-known figures included architect Igor Svoboda and the institute’s chief interior designer Vladimír Kovařík.

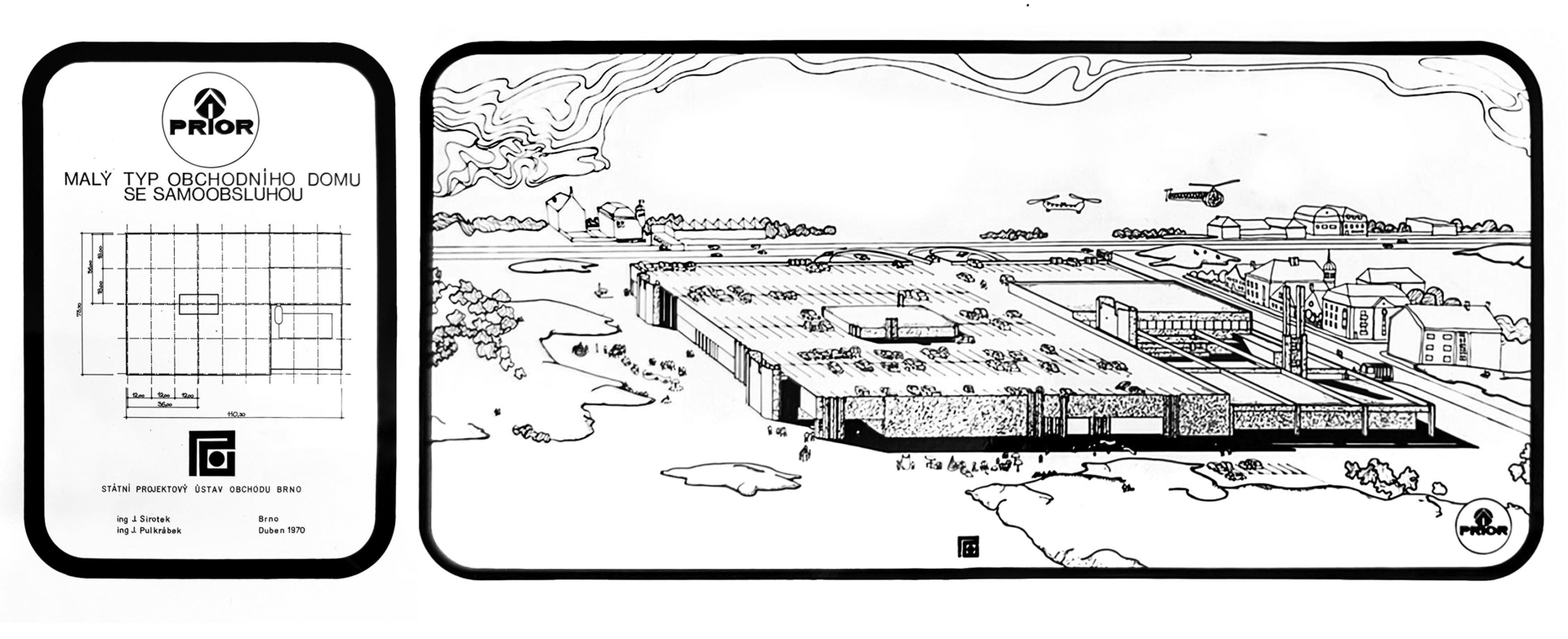

In its early years, the institute focused on developing the concept for a network of wholesale warehouses and storage complexes, as well as constructing hotels to address the country’s acute shortage of accommodation capacity. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, most projects shifted toward retail development, including department stores. An important part of the institute’s work was the publication of standardization guidelines, industry norms, and Technical-Economic Indicators for hotels and trade buildings. Although many of these projects remained on paper, they sometimes constituted up to one-fifth of the institute’s work. From the late 1970s and especially in the 1980s, the institute developed collective typified designs for various store types in multiple size categories. For instance: Self-service grocery store (sales area 300 m², 700 m², 1000 m²), or General-purpose drugstore and household goods store (sales area 300 m²), General-purpose clothing store (sales area 600 m²). This standardization also extended to accommodation facilities and workplace canteens. However, the primary aim of these guidelines was not architectural quality but operational simplicity and efficiency for a given store type at the lowest possible cost. While many of these projects could be seen as “architectural exercises” assigned by the Ministry of Trade, the tendency to use standardized designs for new department stores was also supported by the General Directorate of Prior.53

The ŠPÚO Branch Office in Bratislava

The founding of the Slovak branch of the ŠPÚO was closely linked to the design and construction process of the Prior department store in Bratislava and its author, Ivan Matušík. Aged only 30, this young architect won the anonymous public competition in 1960 called to design a commercial and social complex at Kamenné Square, announced by the Ministry of Trade of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. His design for a department store with a hotel was subsequently realized between 1964 and 1978 according to the original project.54 Based on his success in the competition, the ŠPÚO leadership in Brno decided to establish a branch office where Matušík could work on the project and simultaneously became its leading figure. Although the Bratislava branch had considerable autonomy in terms of design and work organization, Matušík was directly accountable to the headquarters in Brno, where he attended regular meetings.

The branch, like the parent institute, designed a wide range of retail buildings, accommodation facilities, and canteens, wholesale warehouses, administrative buildings, and renovations of existing buildings for trade and tourism, without limitations on investment costs. In Bratislava, due to the underdeveloped Slovak retail network, the branch could not meet all the demands for new department store development, so many projects originated in Brno. In the 1960s, Růžena Žertová designed department stores in Košice (1962–1964) and Michalovce (1964–1968), Jan Melichar designed the Prior department store in Trenčín (1968) and an unrealized project for Prior in Trnava (1970), Jiří Brychta designed Prior in Prievidza (1967–1968), Josef Opatřil designed Prior department stores in Banská Bystrica (1978–1979) and Liptovský Mikuláš (completed by 1981) as well as the Jednota department store in Topoľčany (1974–1978), and František Antl was the author of the ZOD Dargov in Košice (1981–1982).55

Paradoxically, Slovak architects from the Bratislava team hardly participated in designing Czech department stores, despite entering several competitions.56 The most significant contribution was when Ivan Matušík’s team advanced to the final round of the invited competition for the Máj department store in Prague. Moreover, an agreement existed between Matušík and the head of Brno’s Studio 01 under which Brno had a monopoly on hotel and accommodation design in the High Tatras, while the Bratislava branch focused on department stores in Slovak towns.57 Consequently, many hotels in the Tatras were designed by Zdeněk Řihák (Hotel Panorama 1967–1970, Hotel Patria 1968–1976) or his colleagues (Hotel Park by Igor Svoboda, 1966–1969).

As a ministerial institute, ŠPÚO Bratislava primarily designed for the Ministry of Trade as the chief investor. The main investor was a specific enterprise or a trust of enterprises under the ministry’s administration, most often Prior, OTEX, or Nábytok (Furniture Trade), etc. Company directorates planned the construction of new shops and department stores based on statistics about existing retail space in the given towns and the purchasing power of the population, as well as specific requests from regional/district/municipal national committees. According to the architects, there were no precise rules for allocating commissions between studios, and assignments were distributed rather randomly, or rather based on current need. The same requirements applied to the design of trade buildings in both the Czech and Slovak parts of the country. However, architects did not exclusively work on assignments for state trade. Occasionally, they prepared projects for consumer cooperatives (e.g., the department store DODO in Michalovce or Jednota in Topoľčany, and in the Czech lands, the Labe department store for the cooperative in Ústí nad Labem) and other enterprises. In terms of department stores, the most important investor was Prior. Conversely, department stores for the Prior trust’s General Directorate were not exclusively designed by ŠPÚO architects.

The ŠPÚO headquarters in Bratislava was located in the city center on Leningradská (now Laurinská) Street, in part of the Aponyi Palace building. From the early 1970s, the studios were situated in the attic with a built-in gallery, renovated according to a design by architect Fedor Minárik. The architectural and construction center was divided into three workgroups, each with 5–6 members: 3 or 4 architects, a structural engineer, and a draftsman. Group No. 1 was led by Alena Morávková, group No. 2 by Peter Minarovič, and group No. 3 by Fedor Minárik. The institute also employed specialists in warehouse logistics, landscaping, sanitation engineering, large kitchen technologies, an economic designer, and an interior designer for retail spaces – Melánia Ševčíková. A separate group of structural engineers was led by Pavol Čížek. Team composition changed frequently, and there was high staff fluctuation, especially among young architects and engineers.58 Among the institute’s notable figures were architects Ján Bahna, František Kalesný, Andrej Sloboda, Andrej Gürtler, Ľubomír Mihálik, Ivan Kepko, Peter Valach, Karol Rosmány, Mikuláš Bánovský, and in the early years, also Pavol Lichard.

“Matušík demanded strict work discipline and maintained personal distance from employees, but he knew how to appreciate good results and was able to foster a creative atmosphere and healthy competition among architects in the studio.”59

Ivan Matušík was the leading figure of the Institute throughout its entire existence. In addition to the Prior department store in Bratislava, he designed two notable retail buildings at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s – the Slimák [Snail] shopping centre and the department store in Martin – and was involved in other significant department store designs (Prior in Nitra with Pavol Lichard, Prior in Žilina with Fedor Minárik, or Prior in Levice), though his actual contribution to some of these projects is disputed.60 The department store on Kamenné Square, one of the first three Prior stores built in Czechoslovakia, became a key reference point for an entire new generation of department stores across the country. ŠPÚO director Jaromír Sirotek described the work on the Bratislava department store as “an effort to find the face of the socialist department store.”61

He admitted that in the early years of ŠPÚO’s operation, there were very few precedents to follow in department store design.62 Examples and influences from beyond the Iron Curtain were virtually inaccessible, yet within ŠPÚO, there was space for discussion about foreign architectural models. Architects on Leningradská Street followed international trends primarily through foreign architectural journals, which reached the Bratislava branch sporadically from the ŠPÚO library in Brno, and only via the director. Those who managed to travel abroad despite the systemic barriers of the Iron Curtain would, in turn, share their experiences with colleagues by presenting color slides from their trips.

Designing department stores was largely creative work, despite many obstacles inherent to the regime. In terms of form and artistic expression, architects enjoyed considerable freedom, with minimal political interference in this type of architecture – although the decisive factor was always the quality of the proposed design. However, the result was constrained by available technology, materials, and structural systems, all factors dictated by the construction supplier. Operational and spatial layouts had to comply with investor requirements, communicated through the language of budgets, corporate norms, and so-called technical-economic indicators. And as the projects included not only the building itself but also its surroundings – parking lots, ground-level landscaping, and nearby public spaces – the requirements from traffic engineers and heritage conservation authorities also had to be considered. Local urban planning regulations (under the authority of Stavoprojekt) imposed additional constraints regarding scale and materials. Interior design was also limited – architects had to work with equipment supplied exclusively by the state-owned company OZAP [Obchodní zařízení Praha].63

From the 1970s onward, there was growing pressure toward rationalization and standardization in department store construction. This process, through the creation of typological guidelines and repeated projects, became an important part of ŠPÚO Bratislava’s work. Several noteworthy reusable designs emerged under Ivan Matušík’s leadership. Among the smaller examples was the standard design for a small-scale grocery store, P 130 m² (František Kalesný, 1976–1980), realized as part of the “Z” campaign in Malacky, Kopanice, Necpaly, and Zvolen. Among larger projects was the combined shopping centre in Čadca with a 1,600 m² sales area (Ján Bahna, 1977–1981), designed for two different users (Zdroj n. p. – groceries and Domáce potreby n. p. – household goods). This project became the basis for a standardized design to be implemented in district towns across the entire ČSSR by directive of the Ministry of Trade. The aim was to minimize atypical building elements: from the foundations to the structural system, external cladding, and interior fittings, everything was to be made from standardized components. The final ZNS 1600 project was created by architect Andrej Gürtler in 1979 and realized in Zlaté Moravce and Bánovce nad Bebravou. That same year, Gürtler was tasked with developing a standardized design for a combined shopping centre in three size variants (800, 1000, and 1200 m²). Although many such projects never moved beyond the drawing board, a ZNS in Bardejov was built between 1983 and 1986 based on this design.64

ŠPÚO’s most important contribution to typification, however, was not an individual department-store design, but an entire new structural system – ŠPÚO-ZIPP. Developed in cooperation with the national Prior headquarters and the state enterprise ZIPP [Engineering and Industrial Prefabrication Plants], it influenced the appearance of an entire new generation of commercial buildings.65 Until then, department-store designs had relied on the generic reinforced concrete Priemstav skeleton used across many building types. The ŠPÚO-ZIPP skeleton (later developed into the INTEGRO open prefabricated system) was tailor-made for department stores. It was first designed for the Trade and Services Centre on Obchodná Street in Bratislava – a project that brought the ŠPÚO team under Ivan Matušík to first prize in a major architectural-urban planning competition announced by the Slovak Ministry of Trade in 1970.66 Though never realized, the INTEGRO system was later developed and tested alongside the repeatable design of the Prior department store by architect Fedor Minárik, realized in Lučenec (1977–1982), Martin, and Piešťany (1979–1983). Despite the push for typification, construction acceleration, and operational flexibility, there was a growing effort within ŠPÚO in the late 1970s and early 1980s to explore the aesthetic potential of the INTEGRO skeleton.67 This desire was clearly visible in the department stores in Prešov (František Kalesný, Fedor Minárik, 1977–1984), Poprad (Fedor Minárik, Ľubomír Mihálik, Andrej Sloboda, 1978–1981), ZOD Ružinov (Ján Bahna, František Kalesný, Ľubomír Mihálik, Pavel Čížek, Peter Minarovič, 1975–1984), and the Vtáčnik shopping centre in Prievidza (Ivan Kepko, Peter Valach, 1980–1985), where the prefabricated elements of the structural frame were given a visual role and their regular rhythm became an essential compositional feature.**key=68 At the same time, production of unbuilt standard designs continued.**key=69**

Based on an agreement between the Czech and Slovak Ministries of Trade concerning the reorganization of internal trade structures, the Bratislava branch of ŠPÚO was officially transferred on 1 July 1988, into the existing Project and Rationalization Institute for Trade and Tourism (PRÚOCR) under the Slovak Ministry of Trade.70 PRÚOCR was dissolved administratively in 1990 and divided into several new design organizations.71

The Project Institute of Trade and Tourism

The Project Institute of Trade and Tourism [Projektový ústav obchodu a cestovného ruchu – PÚOCR] was established as an independent ministerial architecture institute of the Slovak Ministry of Trade on 1 January 1976. The leading figure was architect Kamil Kosman, who originally worked under Matušík’s leadership. From 1987, the institute was led by Jozef Pintér. The institute was responsible for the project preparation of what were known as “under-limit” orders of the ministry (investment costs up to 2 million CZK), which were assigned by the relevant state enterprises, as well as the reconstruction of existing buildings and urban planning studies for tourism. Two project studios were located in Bratislava: Studio 01 (led by Peter Černo, later by Vladimír Vršanský) and Studio 02 (led by Stanislav Spáčil). Later, an expert Studio 03 was created, focusing on research and rationalization in the fields of retail, wholesale, energy, transportation, and public catering. Another branch, Studio 10, operated in Ružomberok under the leadership of architect Vladimír Aichimský. In 1986, the name of the institute was changed to the Project and Rationalization Institute of Commerce and Tourism [Projektový a racionalizačný ústav obchodu a cestovného ruchu – PRÚOCR]. However, the institute designed only one department store during its existence: the Lamač Department Store in Bratislava (Stanislav Spáčil and Peter Černo, project 1978–1980, construction 1980–1988).

Cooperative Design of Commercial Buildings

Alongside the ministerial project institutes, the cooperative project institutes also played an important role in the design of buildings for trade and tourism. In 1956, the Trade Project SSD [Obchodní projekt Svazu spotrebních družstev] was founded in Prague with a nationwide scope: in addition to the Prague headquarters, which had a development studio and two design centers, regional studios operated in Brno, Ostrava, Plzeň, České Budějovice, Olomouc, and Hradec Králové.72

The Bratislava studio was established in 1957 as a “special project organization for designing buildings for commerce, hospitality, tourism, and other commercial facilities in Slovakia.”73 Until 1969, it operated as part of the Trade Project, and after the formation of the federation, it became an independent project organization under the name DRUPRO.74 In Bratislava, in addition to the headquarters, two studios were formed: Studio 08 (Milena Solovičová, Valentín Gruber, Soňa Lýsková, Oľga Arpášová, Anna Priečinská) and Studio 10 (led by architect Lumír Lýsek, Kamil Čečetka, Peter Bíro, Ivan Gazda, Mikuláš Dolský, Milan Kukelka, Lýdia Tytlová). Studio 12 in Prešov (Andrej Dušenka, Milan Bandžák) was responsible for the design of cooperative buildings in eastern Slovakia, and later a studio was established in Považská Bystrica under the leadership of Ladislav Balušík (Viliam Leszay, J. Hatala, J. Balušíková, Peter Gajdošík).75 The studios functioned similarly to the design work in the state trade sector. Each one employed about 30 people, including approximately 5 “creative architects”, as well as draftsmen and specialists in various technical fields. Throughout the operation of the institute, until 1992, the director was Vladimír Kačka. The Bratislava centers were located from 1976 on the top floor of a newly constructed administrative building of the Union of Slovak Consumers’ Cooperatives on Bajkalská Street, designed by the architects of Studio 10, Lumír Lýsek and Lýdia Titlová.

As in ŠPÚO, in addition to retail buildings, cooperative design also involved proposals for wholesale warehouses, restaurants, hotels, and other tourism facilities (motels, motels, campgrounds, etc.). DRUPRO also occasionally created proposals for other enterprises, such as Hotel Gerlach for Reštaurácie Poprad and for the Domáce Potreby [Household goods] enterprise. From the retail perspective, a significant portion of DRUPRO’s production consisted of smaller mixed retail outlets or shopping centers in villages and small towns, where there was less room for creativity and artistic design solutions, but these were realized in large numbers. While in the 1960s, the focus of the institute’s work was rural areas and peripheral regions of Slovakia, gradually in the 1970s and especially the 1980s, the consumer cooperatives Jednota, following DRUPRO architects’ designs, built a network of department stores in cities throughout Slovakia. Among the significant realizations of Jednota department stores, one can mention buildings in Ružomberok (Anna Priečinská), Nové Mesto nad Váhom (Valentín Gruber), Brezno (Lýdia Titlová), Rožňava (Milan Bandžák), Spišská Nová Ves (Andrej Dušenka), the Shoe House in Tatranská Lomnica (Lumír Lýsek, Soňa Lýsková), and the repeatable department-store design by architect Mikuláš Dolský, built in Sereď, Malacky, Šamorín, and Kráľovský Chlmec. A unique case is the department store in Trnava, where Jednota seized the opportunity and succeeded despite Prior’s intention to build and the existence of a completed project by architect Jan Melichar from the Project Institute of Commerce and Tourism. The Trnava realization, one of the most architecturally striking cooperative department stores in Slovakia, was created from Lumír Lýsek’s prizewinning design in an internal company competition in 1969.

Conclusion

The development of post-war department stores in Slovakia can be considered a case study of a specific architectural typology originating from within the context of the centralized state apparatus of socialist Czecho-Slovakia. Construction of the state’s retail network was conditioned by the economic plan, and its expansion from the late 1960s was closely related to the deliberate focus on strengthening consumption and retail in the country. Direct influences on the form and distribution of department stores primarily arose from two elements of the centralized apparatus: on the one hand, the investor in the form of a state-enterprise trust or a district consumer cooperative, most often the retail bodies Prior or Jednota, determining the location of construction, the size, and the product assortment. Subsequently, the second component entered the process – the relevant project institute and its team of professionals, who created specific architectural solutions within the established budgets, technical and economic indicators, operational schemes, limited material and construction solutions, and standardized interior furnishings.

The production of the studios of the ministerial ŠPÚO in Brno and Bratislava and the studios of the cooperative institute DRUPRO largely overlapped. Due to the nature of the department store as a building type, and the associated pressure toward standardization and rationalization, a significant portion of the production consisted of repeated designs and architecturally less distinctive buildings, although numerous valuable architectural works were designed that significantly influenced the form of Slovak post-war modernism. Specifically, in the Bratislava branch of ŠPÚO, under the leadership of Ivan Matušík, a strong generation of architects emerged, able to see creative potential even in the demand for standardization, to formulate a construction tailored to the specific operation, and then to elevate it to a higher artistic level.

The data presented in the study reveal that from the late 1960s until the end of the 1980s, intense development of department stores occurred in Slovakia, proportionally even greater than in the Czech part of the federation. As a result of cooperation between project institutes, investors, and contractors, the phenomenon of department stores spread across Slovakia, radically influencing the appearance of many Slovak cities from regional centers to industrial hubs, and even rural areas. This was not only about the “Priorization” of (Czecho)Slovakia; consumer cooperatives also played an important role. Their activity significantly contributed to the expansion of the department store network in peripheral areas of the country, although they often competed with the state retail sector even in urban environments. Especially in those places, department stores from Prior and Jednota left a significant mark and became a characteristic feature of many Slovak cities.

This paper was supported by the VEGA agency

(Grant no. 1/0063/24), the APVV agency (Grant no. 23-0101) and Doktogrant 2024 (Grant no. APP0627).

Karolína Králiková

orcid: 0009-0004-2147-4149

Department of Architecture

Institute of History, Slovak Academy of Sciences

Klemensova 19

811 09 Bratislava

Slovakia

DULLA, Matúš, MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta, ANDRÁŠIOVÁ, Katarína, HABERLANDOVÁ, Katarína, TOPOLČANSKÁ, Mária and SZALAY, Peter. 2006. Čo pre nás znamená obchodný dom a hotel na Kamennom námestí? Zbúrame to najlepšie? ARCH, 11, pp. 48–49; MORAVĆÍKOVÁ, Henrieta. 2008. Moderná architektúra v čase a predpoklady jej udržateľnosti: Hotel Kyjev a bývalý obchodný dom Prior, 1960–2008. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 42(3–4), pp. 181–196; MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta, SZALAY, Peter, HABERLANDOVÁ, Katarína, KRIŠTEKOVÁ, Laura and BOČKOVÁ, Monika. 2020. Bratislava (ne)plánované mesto / Bratislava (Un)Planned City. Bratislava: Slovart, pp. 223–234 and others.

KICOVÁ, Monika, BEŇO, Peter and SCHNITZEROVÁ, Nikola. 2021. The Prior Department Store in Košice in the Context of History, Current Structural Alterations and Engaged Preservation. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 55(3–4), pp. 200–211.

KVÍTKOVÁ, Natália. 2019. Heritage Obscured: Undesirable Legacies of the Prior Department Stores in Slovakia. Studies in History and Theory of Architecture, 7, pp. 171–186.

MOOS, Jiří. 2018. Československé a zahraniční příklady obchodních domů. In: Ulrich, P. (ed.). Obchodní dům Prior / Kotva. Historie, urbanismus, architektura. Prague: National Heritage Institute and Czech Technical University in Prague, pp. 37–40, 52–53.

ZERVAN, Marián and MATUŠÍK, Ivan. 2003. Ivan Matušík. Život s architektúrou. Bratislava: Monada.

BIŠŤAN, Matúš. 2020. Archi-tektonika veľkorozponového skeletového systému INTEGRO. Koncept otvorenej architektonickej formy reprezentovaný sériou obchodných domov Prior. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 54(3–4), pp. 224–239.

KRIVOŠOVÁ, Jana and LUKÁČOVÁ, Elena. 1990. Premeny súčasnej architektúry Slovenska. Bratislava: Alfa; DULLA, Matúš and MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta. 2002. Architektúra Slovenska v 20. storočí. Bratislava: Slovart.

GAJDOVÁ, Petra. 2011. Soudobé obchodní domy na území Slovenska. In: Klíma, P. (ed.). Kotvy Máje. České obchodní domy 1965–1975. Prague: UMPRUM, pp. 16–21.

ŠEVČÍK, Oldřich and BENEŠ, Ondřej. 2008. Architektura 60. let. “Zlatá šedesátá léta” v české architektuře 20. století. Prague: Grada, pp. 60–62; Klíma, P., 2011; ULRICH, Petr (ed.). 2018. Obchodní dům Prior / Kotva. Historie, urbanismus, architektura. Prague: National Heritage Institute and Czech Technical University in Prague; BERAN, Lukáš. 2019. Rozvíjet materiálně-technickou základnu maloobchodu. In: Vorlík, P. (A)typ. Architektura osmdesátých let. Prague: Faculty of Architecture, Czech Technical University in Prague, pp. 112–113; SMĚTÁK, Pavel. 2022. Obchod, služby, reprezentace. In: Huber-Doudová, H. (ed.). Architektura všem. 1956–1989. Prague: National Gallery Prague, pp. 115–119; MOOS, Jiří. 2023. Typologie obchodních staveb v šedesátých a sedmdesátých letech 20. století v československé architektuře. Obchodní střediska a obchodní domy. PhD thesis. Faculty of Civil Engineering, Czech Technical University in Prague [online]. Available at: https://dspace.cvut.cz/handle/10467/114071 (Accessed: 19 April 2025).

The term appears in several sources: Ševčík, O. and Beneš, O., 2008, p. 60; ULRICH, Petr and MOOS, Jiři. 2018. Zásady a principy užité při řešení obchodních domů v druhé polovině 20. století. In: Ulrich, P. (ed.)., 2018, p. 80; KLÍMA, Petr. 2011. Výkladní skříně a duch doby. In: Klíma, P. (ed.). Kotvy Máje. České obchodní domy 1965–1975. Prague: UMPRUM, p. 4.

Státní projektový ústav obchodu Brno, 1952–1992, fond K 1. Moravian Land Archives in Brno; Projektový a racionalizačný ústav obchodu a cestovného ruchu š. p., 1988–1996. Slovak National Archive; PRIOR, obchodné domy, generálne riaditeľstvo v Bratislave, 1965–1989. Slovak National Archive.

GOGA, Dezider. 1973. Úspešná cesta socialistického obchodu. Projekt, 15 (3), pp. 2–3.

In the West, the department store phenomenon began to take shape as early as the mid-19th century. While isolated examples appeared in Czech cities even before the First World War, the emergence of this building type in Slovakia can be associated only with the second half of the 1920s. For more on the early development of the department store, see BAHNA, Ján. 1983. Vývoj obchodného domu ako stavebného typu. Projekt, 25(9), pp. 3–6; GERŠLOVÁ, Jana. 2007. Obchodní domy – chrámy konzumu, Historie prvních obchodních domů v Evropě. Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 15(7), pp. 119–128; ULRICH, Petr. 2018. Typologie obchodní architektury v 19. a 20. století. In: Ulrich, P. (ed.)., 2018, pp. 19–33; ELVINS, Sarah. 2019. History of the department store. In: Howard,V. and Stobart, J. (eds.). The Routledge Companion to the History of Retailing. New York, Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 136–153.

While the topic of interwar department stores in the Czech lands has been addressed by several authors, in Slovakia this issue remains largely under-researched to this day (for example CHVALOVÁ, Eva. 2007. Obchodní domy jako „katedrály obchodu a módy“ nejen v éře první republiky. In: České, slovenské a československé dějiny 20. století. University of Hradec Králové, 7–8 March 2007. Ústí nad Orlicí: Oftis, pp. 83–91; KOVAŘÍKOVÁ, Tereza. 2013. Obchodní domy firmy Baťa. Diploma thesis. Faculty of Arts, Palacký University in Olomouc [online]. Available at: https://theses.cz/id/s9y4tk/ (Accessed: 19 February 2025); PAULI, Barbora. 2021. Obchodní domy a počátky konzumu v meziválečném Československu. Diploma thesis. Faculty of Humanities, Charles University in Prague [online]. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11956/147824 (Accessed: 19 February 2025).

Based on the Act of 28 April 1948 on the nationalization of all commercial enterprises with 50 or more active employees (Act No. 120/1948 Sb., o znárodnění obchodních podniků s 50 nebo více činnými osobami [online]. Available at: https://www.e-sbirka.cz/eli/cz/sb/1948/120/1948-01-01 (Accessed: 19 February 2025).

SIROTEK, Jaromír. 1970. 10 let práce Státního projektového ústavu obchodu. In: 10 let práce Státního projektového ústavu obchodu [catalogue]. Brno: Muzeum dělnického hnutí.

SIROTEK, Jaromír. 1969. Výstavba maloobchodních jednotek v jádrech našich měst. Projekt, 11(1–2), pp. 28–33.

Act No. 83/1966 Sb., o čtvrtém pětiletém plánu rozvoje národního hospodářství Československé socialistické republiky [online]. Available at: https://www.e-sbirka.cz/eli/cz/sb/1966/83/1972-01-01 (Accessed: 19 February 2025).

BALICKÝ, F. and ŠÍPEK, L. 1968. Více prodejen – spokojenější nákup. Rudé právo, 50, 2 February 1968, p. 5.

NOVÝ, Otakar. 1980. Soudobá architektura ČSSR. Prague: Panorama, p. 75.

KUNA, Vlastimil. 1973. K čomu sme dospeli, o čo sa opierame. Projekt, 15(3), p. 46.

The development of department stores in the USSR as well as in the “West” was regularly addressed in contemporary literature – including publications issued by the Research Institute of Trade, and periodicals such as Socialistický obchod [Socialist Trade] or Československý architekt [Czechoslovak Architect]. The INTECO conference, focused on trade and attended by international participants, was held repeatedly in Brno.

Ševčík, O. and Beneš, O., 2008, p. 60; Klíma, P., 2011, p. 4; Kvitková, N., 2019, pp. 171–186 and others.

The institute was established in 1950 under the name Institute for Research in Domestic Trade [Ústav pro výzkum vnitřního obchodu].

STEJSKALOVÁ, Lucie. 2011. Urbanistické aspekty navrhování soudobých obchodních domů. In: Klíma, P. (ed.), 2011, p. 24.

For the definition of a department store, see ŠTURSA, Jiří. 1971. Typologie budov obchodních. Prague: Czech Technical University in Prague; DUDEK, Oldřich and PŘIBYL, Lubomír. 1986. Občasnké stavby. Obchodní budovy. Prague: Czech Technical University in Prague; DUFEK, Oldřich, RULF, Vladimír and SOBOTOVÁ, Aloisie. 1963. Nákupní střediska a obchodní domy. Prague: Vydavatelství obchodu.

The first ZOD in Czechoslovakia was the Ještěd department store in Liberec (1970–1979), while the most famous example in Slovakia is the Ružinov department store in Bratislava (1978–1984). More on this topic: see SAJALOVÁ, Zuzana. 1982. Uplatnění sdružených obchodních domů v maloobchodní síti. In: Inteco 82. Symposium s medzinárodní účastí. 3. díl. Brno: Dům techniky ČSVTS, pp. 30–37.

ŠEVERA, Michal. 1983. Jednotné metodické postupy výstavby a modernizace obchodní sítě. Prague: Výzkumný ústav obchodu, pp. 4–9.

HADRAVOVÁ, Zdena. 1985. Materiálně-technická základna obchodu. Prague: Merkur,

pp. 334–335.

BREZNIK, Jozef. 1983. Možnost uplatnění samoobslužných obchodních domů v ČSSR a jejich vliv na úspory živé práce. PhD thesis. Výskumný ústav obchodu, Prague, pp. 32–33; KROC, Stanislav. 1987. Chronologie československého vnitřního obchodu 1944–1987. Prague: Výskumný ústav obchodu.

Brochure of the PRIOR Department Store Trust, 1967, fund A/VIII.1. Veľkoobchod, 1969–1992, box 1. Slovak National Archive; 14 of them, due to their technical condition and standard, were designated as “for end-of-life use” and were not considered in the planning of the retail network concept (Breznik, J., 1983, p. 51).

POSPÍŠILOVÁ, Eva. 1985. Prior už dva roky plnoletý. Socialis-

tický obchod, 31(10), pp. 366–370.

Dudek, O. and Přibyl, L., 1986, pp. 13–14.

FABRICIUS, Miroslav. 1995. 150 rokov slovenského družstevníctva. Bratislava: VOPD Prúdy, pp. 177–183.

Exceptions were rare examples from the Czech lands, particularly the Fashion House and the Food House in Prague.

Návrh koncepcie výstavby obchodných domov PRIOR do roku 1980 v SSR. 1972. A/VIII. Ústredné orgány štátnej správy v rokoch 1969 – 1992: Ministerstvo obchodu Slovenskej socialistickej republiky, 1969 – 1980. Slovak National Archive.

The Research Institute of Trade issued methodological manuals, prepared operational documentation, and addressed specific issues related to the construction of department stores in ČSSR based on requests and in cooperation with the General Directorate of the PRIOR trust. For example: The concept for the layout and operation of PRIOR department stores with multi-level self-service areas from 1977; A model of multi-level self-service layouts for department stores with sales areas of 2,500 and 4,000 m², 1979.

KROC, Stanislav. 1985. Vývoj maloobchodní sítě v letech 1963–1983. Prague: Výskumný ústav obchodu, attachment no. 1.1./1.

Fabricius, M., 1995, p. 181.

Jednotná organizácia riadenia a prevádzky obchodných domov Prior. 1972. Bratislava: Prior, 110 p.

KROC, Stanislav and SAJALOVÁ, Zdenka. 1988. Sortimentně provozní typizace plnosortimentních obchodních domů. Prague: Merkur.

ARKIN, D. 1948. Organisace architektonické činnosti v SSSR. Architektura ČSR, 7(3), p. 82.

By 1974, there were a total of 76 state design institutes in the ČSSR, of which 19 were directly subordinated to federal authorities, 34 to national authorities, and 23 to national committees of the Czech and Slovak Socialist Republics (RŮŽIČKA, Vratislav. 1974. Jubilejní celostátní výstava, 25 let socialistického projektování ČSSR. Architektura ČSR, 33(10), p. 465).

PAŠEK, Karel. 1984. Podmínky tvůrčí praxe architektů v projektových organizacích a složkách. In: Architektura nové výstavby občanské, bytové a průmyslové. 1. díl. Prague: Dům techniky ČSVTS, pp. 69–78.

To the topic of project institutes see: TÓTHOVÁ, Lucia. 2023, (Vý)Stavoprojekt. Trnava, Trenčín, Piešťany. Trenčianska Turná: Projekt Hlava 5; specifically in the 70s: MLYNČEKOVÁ, Lucia. 2022. Project Institutes in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s. Creation in the Conditions of a Centrally Planned Economy during the Normalisation Period in Czechoslovakia. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 56(1–2), pp. 106–115; for issues related to the 1980s, see: BRŮHOVÁ, Klára, MLYNČEKOVÁ, Lucia, VICHERKOVÁ, Veronika and ZIKMUND, Jan. 2022. Architektonická práce, pro systém i mimo něj. In: Vorlík, P. and Guzik, H. (eds.). Ambice. Architektura osmdesátých let. Prague: Faculty of Architecture, Czech Technical University in Prague, pp. 70–90.

In addition to the headquarters in Prague, it had several branches in Brno, Bratislava, Hradec Králové, Pardubice, and Ústí nad Labem. After the autonomy of Slovakia within the federal structure of the common state, a separate design organization – Potravinoprojekt – was established on 1 January 1969, with its headquarters in Bratislava.

VENERA, Mirko. 1973. Potravinoprojekt. Projektový a inženýrský podnik potravinářského průmyslu. Prague: Potravinoprojekt.

Státní projektový ústav obchodu. 1972. Brno: Propagační tvorba Brno.

While Brno started with 101 employees, Prague had 42. The most well-known figure of the Prague Center 10 was Alena Šrámková, who worked there until 1975. Other members of the studio included Anděla Drašarová, Michal Sborowitz, Zdeněk Edel, Jiří Lavička, Jindřich Pulkrábek, and the Brno-based builder Alois Kuba. In the company brochure from 1972, architect Vladimír Bouček is listed as the head. The activities of the Prague center of the State Project Institute of Commerce (ŠPÚO) have been scarcely explored so far and require further research.

The studio was founded based on the work of architects Martin Krupauer and Jiří Střítecký.

See KOS, Lukáš. 2021. Zdeněk Řihák’s Hotel Buildings and the State Project Institute of Trade Brno. Architektura & urbanismus, 55(1–2), pp. 46–59.

Státní projektový ústav obchodu. 1972; According to architect J. Melichar, this division was roughly accurate, but not strict (MELICHAR Jan. 2024. Interview by Karolína Králiková, 4 November, Brno).

In the contribution of the Deputy Technical and Operations Director General of Prior at the Inteco 82 symposium, an intention was presented “to apply repeated designs with progressive technology to the greatest possible extent in the construction of new facilities.” (SZOMOLÁNYI, Pavol. 1982. In: Inteco 82. Symposium s medzinárodní účastí, p. 15).

Moravčíková, H., 2008.

The listed years are of the project design, not of the construction.

Interview with the architect Ivan Matušík (HURNAUS, Hertha, KONRAD, Benjamin and NOVOTNY, Maik. 2007. Eastmodern. Architecture and Design of the 1960s and 1970s in Slovakia. Vienna: Springer Vienna, p. 214).

Based on the oral interviews: KALESNÝ, František and GÜRTLER, Andrej. 2024. Interview by Karolína Králiková, 22 October, Bratislava; MELICHAR Jan. 2024. Interview by Karolína Králiková, 4 November, Brno.

Memoirs of architect Andrej Gürtler, unpublished.

Based on an interview with former employees of ŠPÚO Bratislava Branch: KALESNÝ, František and GÜRTLER, Andrej. 2024. Interview by Karolína Králiková, 22 October, Bratislava.

Architect Andrej Gürtler recalls the collaboration in Nitra as the last and only one before Lichard left the institute due to personal disagreements with Matušík over the authorship of this department store. However, it was not the last time the director became a co-author of a project despite the original authors’ objections.

SIROTEK, Jaromír. 1969. Obchodný dom na Kamennom námestí v Bratislave. Architektura ČSSR, 28(6), pp. 351–357.

Sirotek, J., 1970.

SÝS, Václav. 1986. Zařízení pro obchodní domy. Socialistický obchod, 32(2), pp. 64–65.

Memoirs of architect Andrej Gürtler, unpublished; GÜRTLER, Andrej. 1988. Združené nákupné stredisko v Bardejove. Projekt, 30(6), pp. 12–14.

The director of the trust, Ing. Vlastimil Kuna, provided the State Project Institute of Trade (ŠPÚO) with clearly specified guidelines for the development of the system, which facilitated not only its creation but also its widespread application in newly designed department store buildings. The requirements included: 1. a column grid with a minimum module of 9 × 9 m, 2. a basic floor plan modulation in multiples of 1.2 m, 3. the possibility of concealed routing of both horizontal and vertical utilities within the designated space of the structural elements, etc. (Bišťan, M., 2020, pp. 231–232).

ZÁRIŠ, František. 1969. Súťaž na obchodno-spoločenské centrum v Bratislave. Projekt, 11(1–2), pp. 18–23; KARFÍK, Vladimír. 1971. Centrum, na ktoré sa čaká. Projekt, 13(4), pp. 185–195.

The emphasis on variability and operational functionality – prevailing over any self-serving pursuit of originality – was also reflected in a contribution by Z. Jiřička, director of SPÚO (JIŘIČKA, Zdeněk. 1985. Úloha projektových složek obchodu při zajišťování nové výstavby. In: Inteco 85. Celostátní symposium k tématu Uplatněním poznatků vědecko-technické revoluce k dalšímu rozvoji obchodu do roku 2000. Karlovy Vary, 19–21 March 1985. Plzeň : Dům techniky ČSVTS, pp. 115–125).

Among them only the Vtáčnik shopping centre remains still standing.

In the second half of the 1980s, several standardized projects of Integrated Department Stores (ZOD) stood out: ZOD 4000 (1988 – Ján Bahna, Marián Fábry, Viktor Ostrolucký – structure), ZOD 3000 (1985 – Ján Bahna, Eva Kleinová, Viktor Ostrolucký), and ZOD 2000 (1986 – Peter Minarovič, Ján Bahna, Viktor Ostrolucký); Typizační práce SPÚO 1970–1985, fund K 1 Státní projektový ústav obchodu Brno, 1952–1992, box no. 9. Moravian Land Archive.

This was accompanied by the relocation of the institute’s headquarters from the city center to the Ružinov district, into an administrative building on Urxova Street (Záverečný delimitačný protokol, fund K 1 Státní projektový ústav obchodu Brno, 1952–1992 box no. 2. Moravian Land Archive).

Part of the original staff of the ŠPÚO branch established the design studio ProLinea (with Fedor Minárik as the new director), while the architects of PRÚOCR became part of the Studio of Trade and Tourism (headed by Vladimír Vršanský), and the research division formed TERNO – the Research and Development Institute of Trade and Tourism. In Ružomberok, the branch office (until 1988 known as Studio10) was transformed into the studio PROJEKTING Ružomberok. (Rozhodnutie ministra obchodu a cestovného ruchu Slovenskej republiky o rozdelení štátneho podniku Projektový a racionalizačný ústav obchodu a cestovného ruchu so sídlom v Bratislave, Urxova 1, 21.6.1990, fund H/I. Veda: Projektový a racionalizačný ústav obchodu a cestovného ruchu š. p., 1988 – 1996, box no. 1. Slovak National Archive).

SŮVA, Stanislav. 1970. Obchodní projekt SSD. Projekty-realizace. Prague: Obchodní projekt.

DRUPRO [promotional brochure]. 1971. Bratislava: Zväz slovenských spotrebných družstiev; Company promotional brochure DRUPRO: Stavby spotrebných družstiev na Slovensku 1955–1985 states the year of establishment as 1955.

According to architect Lýdia Titlová’s recollections, cooperation with the Prague headquarters was extremely beneficial. DRUPRO architects regularly traveled by plane to Prague for so-called technical councils. After the Bratislava institute became independent, they often missed the Prague model, and “suddenly had to solve everything on their own,” as the architect recalled (based on an oral interview: TITLOVÁ, Lýdia. 2024. Interview by Karolína Králiková, 29 November 2024 in Bratislava).

The listed architects do not represent a complete roster of the staff in the various DRUPRO studios. From its founding until 1985, the number of employees in the enterprise grew from 15 to 160. By 1985, the enterprise had undergone a reorganization, and its branches were newly designated as Studio 01 Bratislava, Studio 02 Považská Bystrica, and Studio 03 Prešov (Company promotional brochure DRUPRO: Stavby družstevného obchodu 1955–1985).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.5

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License