At the start of the millennium, many settlements that were originally villages at the suburban edge of Prague saw their populations multiply several times, yet without corresponding growth in the capacity of civic infrastructure and accompanied by a notable erosion of social cohesion or local identity. This study draws parallels between two radically diverging paths followed, thanks to decisive mayors and “their” architects, by two originally small historic villages: Líbeznice and Dolní Břežany. It examines the entire range of actors standing behind the development of these two settlements, their differing visions for the future, the social capital (Bourdieu) and processes leading to their fulfilment, and the current physical forms of both settlements.

Suburbanization has been one of the most striking changes in the settlement structure of the Czech Republic over the past three decades, as well as a process with extensive reflection among professionals as well as the media. However, this reflection has largely been confined to urban geography and affiliated disciplines.1 Researchers in architectural theory and history have usually acquiesced to the narrative on suburbia as an economic, ecological, transport, social… and only secondarily an urbanistic and architectural problem, as summarised two decades ago in the first major Czech study on the topic, Pavel Hnilička’s Sídelní kaše [Urban Sprawl].2 In short, it is not a theme addressed by the history or theory of architecture. Yet is this rejection not essentially the same approach once taken toward socialist-era housing estates? In parallel with the increasing body of scholarship in the past decade addressing the once-denigrated prefabricated apartment block3, a fresh analysis of Czech suburbia might well reveal that not all satellite towns are identical and that some of them may deserve serious attention as architectural formations.

In the present study, I intend to use the example of two villages lying just beyond the Prague city limits to reveal how urbanistic conceptions and architectural designs for public space and important buildings can contribute to the preservation or the redefinition of local identity, as well as reinforcing the position of the locality among other settlements in Prague’s suburban edges. Specifically, I examine two settlements whose names appear in architectural journals or yearbooks or receive various professional awards significantly more often than their neighbours: Líbeznice and Dolní Břežany. Both villages are repeatedly cited as positive examples or models for the development of suburban settlements. As such, they are exceptional cases, yet equally they clearly represent two diverging developmental trajectories followed by other settlements in the metaphorical gravitational field of Prague.

Neither settlement is a satellite town erected rapidly on a greenfield site devoid of any context, but instead a historic village which, in the decades after the Velvet Revolution of 1989, became surrounded by new residential construction that radically changed the size and the composition of its population. Comparison of the recent development of these two sites is also relevant considering the similar commuting distance from central Prague, the similar initial population figures, the strong role of an active mayor, and the engagement of respected architects. Equally similar are the visions which both long-serving mayors voiced upon assuming their offices: to cite the words of one, Věslav Michalik, shifting “from transformation into an overnight shelter toward the growth of Břežany into a viable town”.4

Yet even a brief visit to the two villages will leave in the visitor a markedly different impression. Today’s Líbeznice has grown organically out of the village’s historic structure, around a clearly discernible centre. Despite the intensive building of single-family houses in the past decades, Líbeznice remains essentially a compact, internally structured urban entity, preserving its rural character yet offering high-quality public facilities. Dolní Břežany, which openly calls itself the “village-capitol of contemporary architecture”,5 has even at first sight far greater ambitions. It provides a model instance of anthropocenic hybrid form, bringing together quite disparate entities: town and landscape, village, city, suburb, periphery.6 Besides the original chateau (now a hotel), the central dominant of the village is the complex of modern research institutes, and the new square sided with five-storey apartment blocks.

To answer how the results of these parallel efforts towards worthwhile development emerged so differently, our approach must necessarily be a complex one, particularly in the difficult interval between the (recent) past and the present. Hence it uses, alongside methodologies from contemporary architectural history, critical analysis both of verbal discourse and the built architectural or urban forms of both villages. However, even if expert urbanistic planning may foreshadow the later development of the sites, no less vital, it turns out, are the abilities of local politicians, primarily mayors. These key individuals not only formulate unifying visions of the future and convince voters to back them but can equally assist in acquiring or retaining land for public buildings, providing finances, hiring specific architects, or enticing private investors. This perspective of the individual actions of these prominent and charismatic figures is treated through the idea of multiple categories of capital (here primarily social, cultural, or political) as introduced by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu.7 And by way of conclusion, I intend to examine the values expressed by the resulting physical / built forms of both villages, their links to the past, and their openness toward the future.

The Villages

Líbeznice lies north of Prague, about 18 km from the city centre. First mentioned in records from the 13th century, it gained the Church of St. Martin in the village centre in the 14th century. By the 19th century, Líbeznice was a compact village with a church and a group of small fishponds; during the later decades of the century a sugar-refinery began operations, and a school was constructed.8 During the 20th century, the gradual addition of single-family houses with gardens began, primarily in the village’s southern section.9

At the end of state socialism, Líbeznice had around 1,400 residents. After 1989, the demographic curve originally registered a sharp drop, followed by a rise in the later part of the 1990s. A more pronounced increase in population – and hence construction – occurred after 2006, while in recent years the demographic situation has stabilized. As of 2024, Líbeznice had 3,211 residents, with an average age of 36.6 years.10

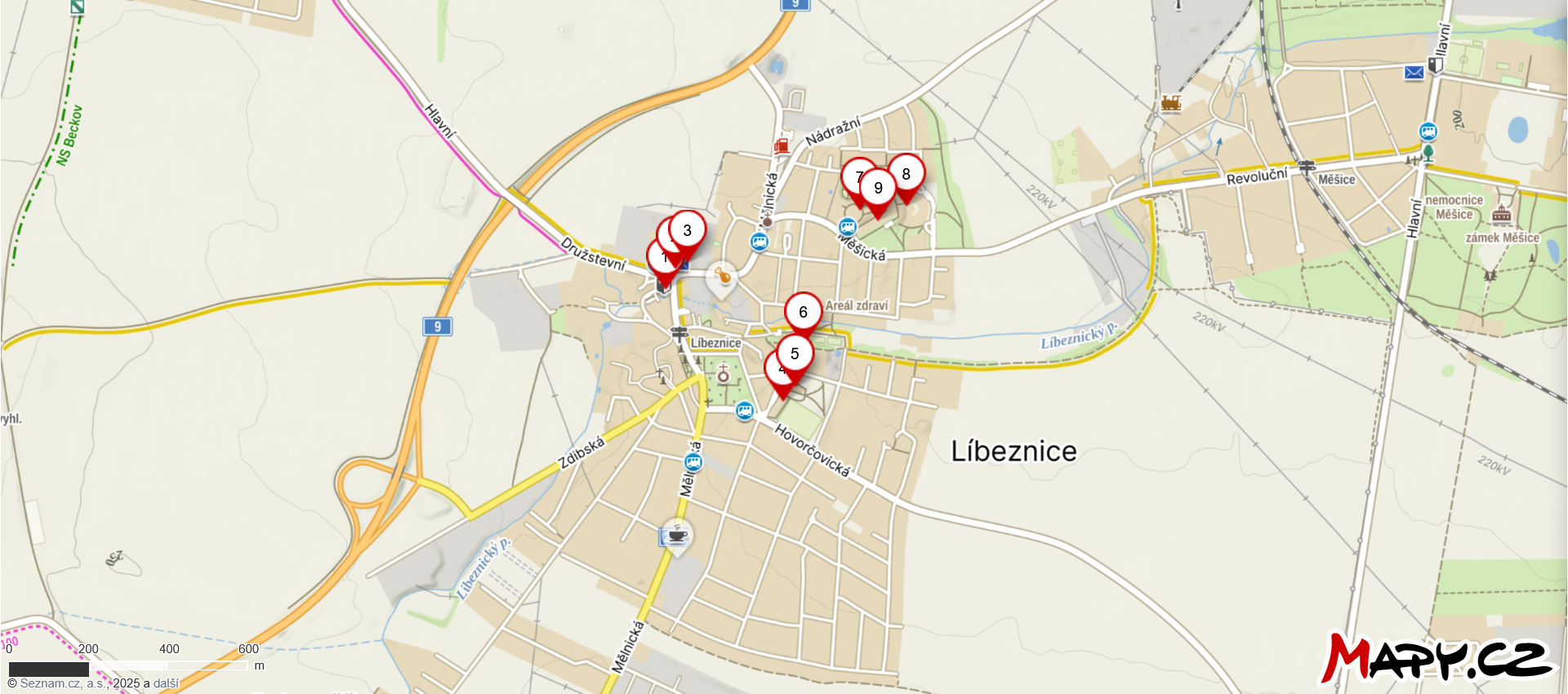

Essentially, there are now nearly three times as many people residing in the village as there were thirty years ago, and there can be no doubt that this growth is the outcome of the process of suburbanisation: the new inhabitants largely rank among the middle class, able to purchase their own single-family residences, while the low average age reveals that the new arrivals consist largely of young families. This population increase was matched, though with a certain delay, with construction of public facilities, mostly after the election of mayor Martin Kupka in 2010. By way of introduction, even a brief listing of the new-built or reconstructed public buildings over the past 10 years is impressive: reconstruction of the municipal office and service centre (M1 architekti, 2014), new pavilion for the primary school (Projektil architekti, 2015), reconstruction of the main square, Mírové náměstí (ateliér Vyšehrad, 2015), the new sports hall (M1 architekti, 2016), the skatepark in the Health Complex (Areál zdraví, Mystic Constructions, 2016), the additions to the primary school and the children’s art school (M1 architekti, 2017), the new primary school building (Grulich architekti, 2019), the new facilities yard with fire station and renovation of the historic locality U kola (Ehl&Koumar architekti, 2020 and 2021). For a village of just over three thousand residents, these are projects quite demanding both financially and organizationally, moreover all completed in rapid succession. And even more notably, perhaps uniquely among Czech towns and villages, all these works were designed by studios (perhaps with the one exception of the not very well known studio Grulich architekti) that rank among the leading practitioners on the national level.

Dolní Břežany lies to the south of Prague, but at a similar distance from the centre as Líbeznice, roughly 18 kilometres. Archaeological finds confirm human settlement in the locality as far back as the late Stone Age, though the first written references to the village date from the 14th century. In the 16th century, the village had its own gristmill and brewery, with the chateau completed toward the century’s end. At the start of the 18th century, the Břežany estate was purchased by the Archbishopric of Prague, which retained the property up until 1945. Maps from the 19th century and historic postcards show a relatively small village settlement surrounded by fishponds and dominated by the chateau, though also with the landmarks of the brewery and the school, and the immediate vicinity consisting of fields and orchards.11 An aerial photograph from the 1950s already reveals a visible expansion of the village northwards, i.e., toward Prague;12 a new school was constructed in Břežany in 1984.

Unlike Líbeznice, where the village centre was historically defined by the church, the settlement structure of Dolní Břežany was less legible, since the space of the historic village green was partially obscured by the major roadway passing through it. After 1989, moreover, the core locality around the remainder of the green, the local government office, and the chateau was degraded by the decrepit complex of the former collective farm, which gradually decayed into a brownfield.

At the end of state socialism, there were just under a thousand residents of Dolní Břežany, and even during the 1990s the village saw little growth. Development appeared only in the new millennium: by 2008 the village had a population of 2,476, by 2024 reaching 4,694.13 Hence, over the past three decades, the number of inhabitants almost quintupled – though it should be said that these numbers are for the entire administrative area, which includes not only Dolní Břežany, which will be the primary focus of interest, but also the purely residential settlements of Lhota, Jarov, and Zálepy.

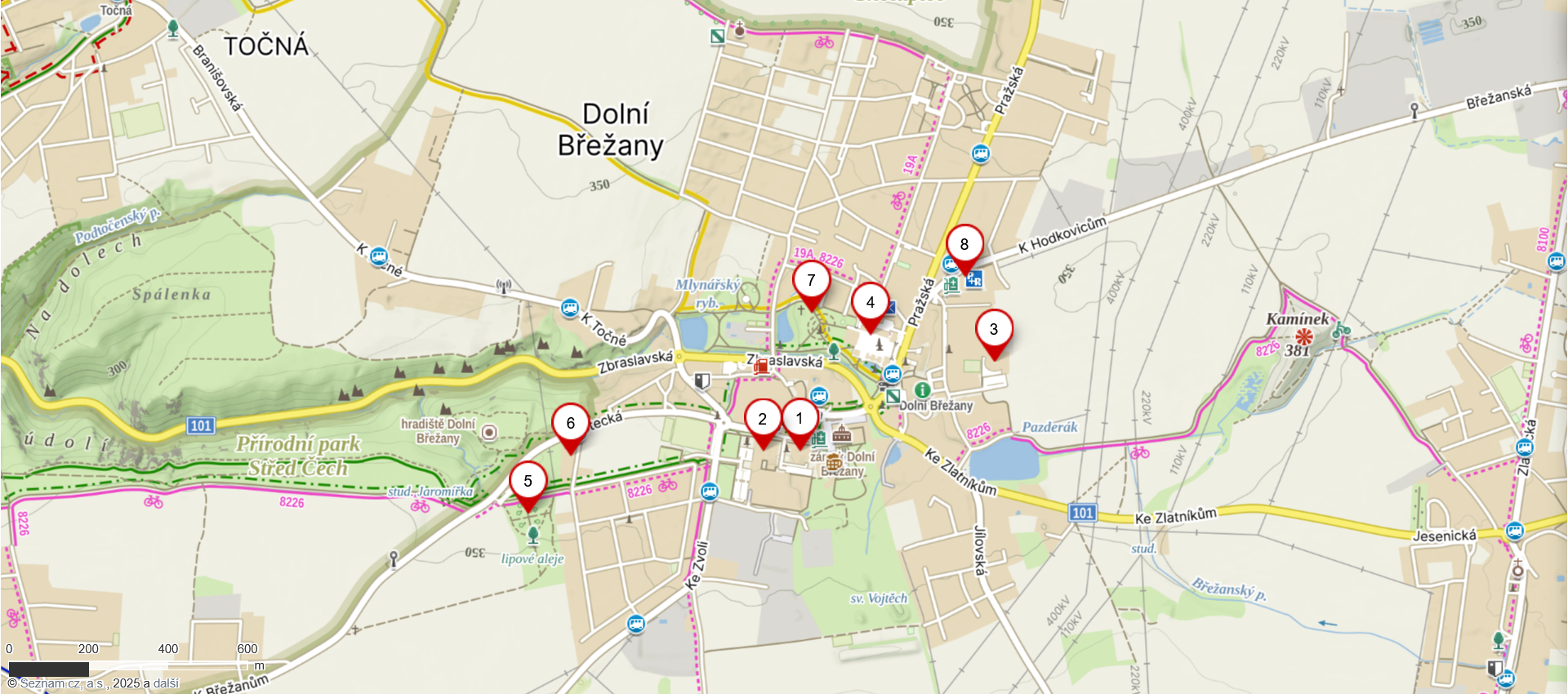

The listing of public buildings realized in recent years in Dolní Břežany is, if anything, even more impressive than in Líbeznice and is similarly connected to new leadership in local government, specifically the former mayor Věslav Michalik (after 2004): the Celtic and Millers’ Park (Keltský a Mlynářský park, Ateliér zahradní a krajinářské architektury, 2010), the laser technology research centres HiLASE (Len+k architekti, 2014) and ELI Beamlines (Bogle Architects, 2015), the reconstruction of the children’s art school (Pavel Hnilička Architects + Planners, 2015), the new cemetery (Ateliér zahradní a krajinářské architektury, 2016), the sports hall (Sporadical, 2017), the kindergarten (S.H.S architekti, 2020), the parking garage (Fránek Architects, 2021) or the viewing tower on the hill Závist (Huť architektury Martin Rajniš, 2022). The financial volume of investment, primarily in the two laser centres, is approximately 9 billion CZK (85 % of the investment provided by the EU), significantly exceeding the conditions of this small settlement. Here as well, it is possible to find exceptional architecture, though hardly in all cases. The most controversial aspects are the scale of the new buildings and their relations to the context of the original village, as well as to each other.

The Actors

Invariably, architecture and urbanism bring into play a significant range of actors, motivations, requirements, and limitations. Simplifying matters down to the most essential, we arrive at the triad of investor – architect – state. In particular, the last-mentioned actor becomes involved in the planning and realization process in many forms and roles, from elected representatives to civil servants, from the European to the national to the local levels. Often, local governments also hold the position of investor, whether in acquiring urban masterplans or in realizing larger or smaller public buildings. For this reason, in the following text I intend to devote my attention to the representatives of the relevant local governments, and to an extent likely more thorough than is usually the practice in architectural history.

The post-1989 transformation brought in its wake significant changes in the positions and powers of these actors regarding the treatment of spaces and land, not only in suburban settlements – weakening the influence of regulation, expert planning, and control on the state and regional levels, while shifting most competences to the local level, primarily that of municipal and village governance.14 Hence the key actor in the development of any specific urban entity became the local elected representatives, who had the decisive word on formulating the requirements for the masterplan and its subsequent approval. Yet if a municipality hires and pays the preparer of the masterplan, the degree of expert independence becomes significantly restricted. In practical terms, it has repeatedly been the case that the chief agent in the development of a settlement, primarily among smaller ones, is the elected mayor.15 Essentially, it is his or her capabilities, values, motivations, goals, or no less social and cultural capital that become the vital determinants of the direction in which the settlement’s development will proceed.

Only rarely in the Czech context, though, is this role of local leadership as strongly displayed as in the two selected villages. Their apparently similar, or even parallel roads toward success are directly tied to the exceptional competences, ideas, and even more social or cultural capital of two concrete individuals: Líbeznice’s mayor Martin Kupka (Civic Democratic Party – ODS, in office 2010-2021) and Dolní Břežany’s mayor Věslav Michalik (Mayors and Independents Party – STAN, in office 2004-2022). Yet the current form of both village-suburbs, their settlement structure, the structure of values they symbolize, and the overall “image” all equally reveal the great divergences in the approaches of both mayors and the influences of other involved actors, whether urban planners and architects or investors. Who, then, are these two key players, who were their associates, what types of Bourdieuean “capital” did they draw upon, and what ideas did they bring to fulfilment in the villages they governed?

The Mayors

Martin Kupka (*1975) studied journalism at the Charles University Faculty of Social Sciences and initially made his career in governmental public relations: first as press spokesperson for the Prague municipal government, then for the Central Bohemian regional government (2003-2008) and the national Ministry of Transport.

Kupka joined the centre-right party ODS in 2008, and since 2014 has been a deputy chair. From this point onward, his political career truly took off: 2016-2022 in the Central Bohemian regional assembly, since 2017 in the Czech Parliament. In 2020, he was appointed deputy to the regional governor of Central Bohemia, Petra Pecková, in charge of road transport, then after the 2021 parliamentary elections became the national Minister of Transport. Upon assuming this post in the cabinet, Kupka resigned as mayor of Líbeznice.16

With his education and experience in PR, Kupka could orient himself quickly in a new topic or situation, as well as his skill in communicating and persuading. Equally, he held strong social capital: as the former Central Bohemia regional governor Petr Bendl related in a recent article in the weekly Respekt, Kupka was able to travel throughout the entire region while serving as his spokesperson and expanding his own contacts. “He became better and better known, which gave him space for growth.”17 Primarily during his work in regional government, Kupka also became acquainted with matters involving grants and subsidies; in turn, he gained managerial experience as the head of media teams and press departments. And his public image as a hard-working and polite young man has remained unusually stable, untarnished by any significant scandal. Indeed, the perfection of this image attests to another exceptional competence of Kupka’s – the ability to move safely through today’s complicated media sphere. This entire grouping of cultural and social capital is what Kupka turned to great effect during his long term as mayor of Líbeznice.

To be elected mayor of a small village at the age of 35 might, at first, seem a major career setback, since in doing so he relinquished the more prestigious post of cabinet spokesperson. Yet it turned out to be his first step into genuine politics, where “[y]ou can change things and also see how they are reflected in people’s lives.”18 The flourishing of Líbeznice, which thanks to its exceptional architecture gradually achieved media recognition,19 is itself a symbolic parallel to the strengthening of Kupka’s position in political life.

Věslav Michalik (1963-2022) was over ten years older than Kupka, hence his studies and early career took place still under the state-socialist order. He graduated from the Faculty of Atomic and Physical Engineering at the Czech Technical University (ČVUT) and well into the 1990s continued to work as a researcher at the Academy of Sciences, including a research period of several months in the USSR in 1989 at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna near Moscow. In 1994, he left the academic sphere for finance, where again he rapidly established a highly successful career as a financial analyst.20 Later, he worked for consulting firms and engaged in independent business activity, mostly involving solar energy.21

Elected mayor of Dolní Břežany in 2004, he gradually realized that “the political world was more interesting than the financial one”.22 Unsuccessful in his run for the regional assembly in 2008, he managed to win on his second run in 2012 (non-partisan candidate for the centrist party STAN, then a party member after 2013), and defended his position again in 2016 and 2020.23 From 2020 to 2022, he was deputy to regional governor Petra Pecková in charge of finance, strategy, and innovation – hence active in regional government at the same time as Martin Kupka, who held his own post in 2020-2021.

In 2021, Michalik was proposed by STAN as a candidate for the post of Minister of Industry and Trade in the new cabinet of Prime Minister Petr Fiala. However, journalists from the server Lidovky.cz drew attention to controversial aspects of Michalik’s business career,24 along with the possible conflict of interest between the function as minister and his ownership of large solar power stations receiving state subsidies. Michalik denied any wrongdoing, but withdrew his candidacy.25 As such, he did not follow the career trajectory of the other mayor, Martin Kupka, who became transport minister in the same government. Unfortunately, Michalik unexpectedly died suddenly in the summer of 2022.

Like Martin Kupka, Věslav Michalik had significant cultural and social capital to use for the development of Dolní Břežany: excellent orientation in financial matters, wide contacts with business and political spheres, capability as a manager. As will be further shown, of key importance for the physical development of Břežany were not only his private business ventures but equally his contacts during his early scientific career in the Academy of Sciences. The ambitious transformation of Dolní Břežany, with its many architectural highlights, became part of Michalik’s political image, just as Líbeznice was for Kupka. That he “transformed a village at the western edge of Prague into a modern technological and innovation centre as well as a pleasant place to live”26 helped Michalik’s media image for many years despite the questions surrounding his business, even though these doubts already were voiced as early as 2010.27

Líbeznice for Itself

A significant step taken by the new local assembly, which assumed governance of Líbeznice under Martin Kupka’s leadership after the 2010 election, was the commissioning of a good masterplan. It was no accident that the commission went to the architects of the Prague atelier M1 – Kupka had already worked with them as head of the press committee of the Central Bohemian region (realization of the regional Information Centre, completed 2012). He invited them to the public tender for the plan and, following the recommendation by the expert committee, M1 was issued the commission. The resulting document was approved by the assembly in 2015.28

The architects from M1 had previously never worked on an urban plan (nor have they since), though they did have experience with several land-use studies, primarily with the realization of public buildings (the Faculty of Natural Sciences of Palacký University in Olomouc, 2009; the reconstruction of the former Jesuit monastery in Kutná Hora as the Central Bohemian Gallery, 2014). Hence, they were able to provide a more multifaceted view in their plan – not only of a typical “zoning plan” but a genuine strategy for the village’s growth, connections, and priorities, with emphasis on public space and civic amenities and setting clear borders to the built-up area. However, the plan was not the last instance of the village’s cooperation with the studio: architects from M1 also realized the reconstruction of the local government office and service centre (2014), the new sports hall (2016), the enlargement to the primary school and children’s art school (2017) as well as the landscaping of public spaces and vegetation in various parts of the village. Architect Jan Hájek (*1971), one of the three partners in the firm, became the unofficial “village architect”.29 Equally, thanks to his presence, the architectural competitions held in this small settlement received submissions from architects of prominence. Alongside M1, those who most significantly shaped Líbeznice’s current form were the team of Lukáš Ehl and Tomáš Koumar, formerly close collaborators with Alena Šrámková, responsible for the fire station as well as the landscaping of the public spaces and streets in the village’s oldest part, the historic locality “U Kola”.

The third member of the triad of the essential actors in designing and construction – the investor – brings us back, in the case of Líbeznice, to Martin Kupka and his partners in the local assembly. Here, the municipality, unlike in Dolní Břežany, was the investor for all major construction projects. The overwhelming majority of investment for the reconstruction, enlargement, or new construction of public buildings and the landscaping of public spaces, which under Kupka’s time in office reached many hundreds of millions of crowns (the new school alone costing 240 million CZK), would not have been possible without subsidies. “Without the help of regional, national, or EU funding, there simply would be no investment. So we keep polishing the doorhandles of all sorts of institutions, which is often an activity at the very bounds of human dignity”, was the comment from Kupka at the very outset of his term as mayor.30 His personal acquaintances, mostly on the level of regional politics and administration, wide range of contacts, and ability to present information understandably and convincingly held a vital role in Líbeznice’s success in the process of winning subsidies.

What was the vision of the future Líbeznice that the mayor and his architect, along with other creators, managed to fulfil in the next decades? The initial plans were anything but ambitious, concentrating on countering the “debt in terms of sufficient public facilities”, merely to match the rapid growth in population. The priorities of the “Integrated Plan for Local Development” from 2011 in fact sound quite modest: improvement to local roadways, cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, cultivation of public spaces. Only after them do more complicated goals appear, such as modern public administration, improvement of public buildings, support for the local community, and “strengthening the role of the municipality as the natural centre of the wider area” – along with “a sharp halt of future construction”.31

These ideas also made their way into the 2015 masterplan from M1. Through height regulation, the authors supported the democratic hierarchy of the village, emphasizing the central public buildings, while also surrounding Líbeznice with an outer ring of park (Okružní park) and a belt of trees, setting the clearly delineated and uncrossable boundary for construction. Also indicated in the masterplan are localities for construction of additional public facilities.

Significant as well is the unambiguous stance of the document toward the further suburban expansion of the village, even in the long term: “If in the future demands will be made for expanding the areas of buildable land, make sure that the all the extent built-up or buildable tracts have first been fully used. For future waves of construction, they should be positioned only in the period around 2020 and 2030 and should also be gradually staggered so that the local infrastructure has time for sufficient extension of capacity, and not to collapse under a huge expansion of population. For buildable land, it should not cross the village boundary as outlined by the ring of parkland, preserving the density of the settlement and the openness of the landscape.”

The ideal Líbeznice, for its mayor and architect, thus drew upon the original village structure and scale, where the central landmarks remained the church and the municipal structures and the settlement kept its clear boundaries, yet also devoting maximum attention to the quality of the public space and all public buildings. Its residents should be provided with all that is necessary for worthwhile life and all types of activity – from schools and a medical centre through sports grounds or facilities for cultural and social events up to parks and natural localities. The apt motto for the cooperation between architect Jan Hájek and the municipality of Líbeznice was “An Appealing Líbeznice”.32

Of course, most of the residents would continue to commute to Prague for work, but would still regard Líbeznice as their true home. Children would attend school and adults spend their leisure hours there, creating a network of social ties and improving their village both in the material and the political-social senses. The gradual transformation would here occur primarily from within, rising from below, out of the needs and ambitions of its citizens, the mayors they elected, the municipal architect, and public funding (though here acquired through national or EU subsidies).

Břežany for the World

Planning the development of Dolní Břežany was the work, alongside the ambitious mayor Věslav Michalik, of the young architect Anna Šlapetová (*1973, initially Kovářová), a recent arrival in Břežany who joined Michalik in the local assembly after 2002. She became head of the new-founded architectural and planning commission, then after 2014 officially held the post of municipal architect. The portfolio of Anna Šlapetová primarily contains private houses, except for the remodelling of the school buildings in Břežany. As she herself admitted in an interview from 2016, at the start the village essentially had to “learn to have an opinion”: “When we started addressing the question of what to do with the village in 2003, we basically had no idea where we should create its centre.”33

Central for the future of the settlement were consultations with urban planner Miroslav Baše and the designs where his students tested various possibilities for developing the central section of the village. Even at this point, according to Šlapetová, the idea was already in place of two centres for Dolní Břežany – a square with retail and services and a scientific-technological centre.34 “We didn’t want to make Dolní Břežany into a village in the traditional spirit around a new central green. Břežany always indicated its path to be a town – a small town near Prague”, is how Šlapetová characterizes the views at the time. In the strategic plan, approved in 2003,35 it was already assumed that construction would involve an entirely new “living town centre”, where “it will be necessary to harmonize public interest with the interest of private investors” and the future construction of a further unspecified “facility for science and research”.

What caused this still-small settlement of 1,700 residents to “indicate its path to be a town” is not explained in more detail by Šlapetová, though it is possible to conjecture that this key idea was furthered by architect and planner Miroslav Baše. In fact, in 2004 he published an article entitled “The Process of Suburbanization”, devoting extensive space to the concept of “edge cities” first popularized a decade previously by the American researcher Joel Garreau. This term was applied to the accelerated “new towns” that began to appear in the 1970s and 1980s, emerging out of original commuter suburbs at the edge of large metropolises and acquiring their own commercial and manufacturing facilities, or conversely office complexes, and becoming destinations for work commuting of their own.36 Precisely such an “edge city” was the intention for Břežany, though hardly spontaneously, as with Garreau’s prototypes in the USA, but through urban planning. In turn, this vision also corresponded to Baše’s ideal of the polycentric city in his urban-planning thought.

After Věslav Michalik took office as mayor in 2004, the extant masterplan was significantly altered, followed by preparations for creating a new one. The new masterplan, approved in by referendum in 2009, was prepared by the studio AURS, specifically by the longstanding expert in town and regional planning Milan Körner (*1944), yet after the plan’s approval the municipality did not continue to work with him in any way.37 In contrast to the masterplan for Líbeznice, the one in Dolní Břežany did not articulate any clear concept, beyond wording about Břežany as the centre of its microregion, about “developing green areas” and a further unspecified “transformation of certain sections of built-up area”. What is, though, noteworthy is the implementation of development staging, I other words slowing down further residential construction, as well as the condition of creating regulatory plans or land-use studies for development localities. Also brought into the masterplan was one of the key decisions by the municipal government – the creation of a new square and a large park on the site of the former fishpond, later filled in with construction refuse.

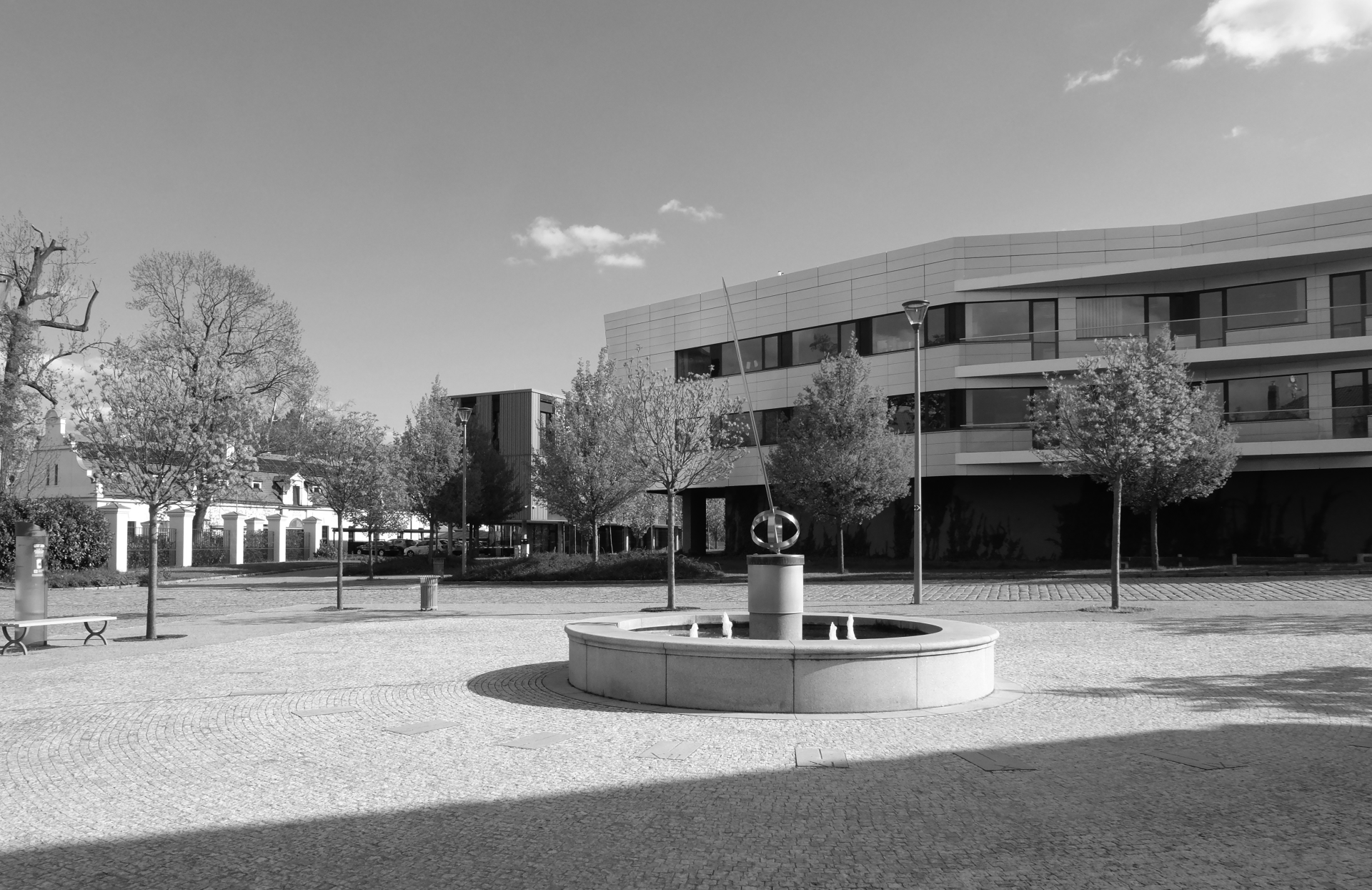

Unlike Líbeznice, where the modern trajectory of the village remained in continuity with its historical structure, the decision in Břežany was for a completely new arrangement. In the 2016 interview, Šlapetová even stated that Břežany “had no centre whatsoever”: “There was nothing of the kind here. Everything was built from square one …”38 As previously noted, there was something of a historic core to be found in Dolní Břežany: there was and still is a discernible green with the Baroque sculptural composition of Christ on the cross with Mary Magdalene kneeling at his feet, along with the building of the town office, while close by stands the chateau with its own chapel and park. Michalik and Šlapetová, though, saw no possibilities in the original structuring of the village, or for some reason wished to see none. Their vision was an actual town square.

At this moment, several actors entered the development of Dolní Břežany whom we did not encounter in Líbeznice – large-scale investors whose realizations now decisively create the identity of the place. The result, in turn, is a more complicated and overlapping network than in the other village, yet one that also displays all the more sharply the role of mayor Věslav Michalik and his cultural and social capital, whether in business or in the academic world.

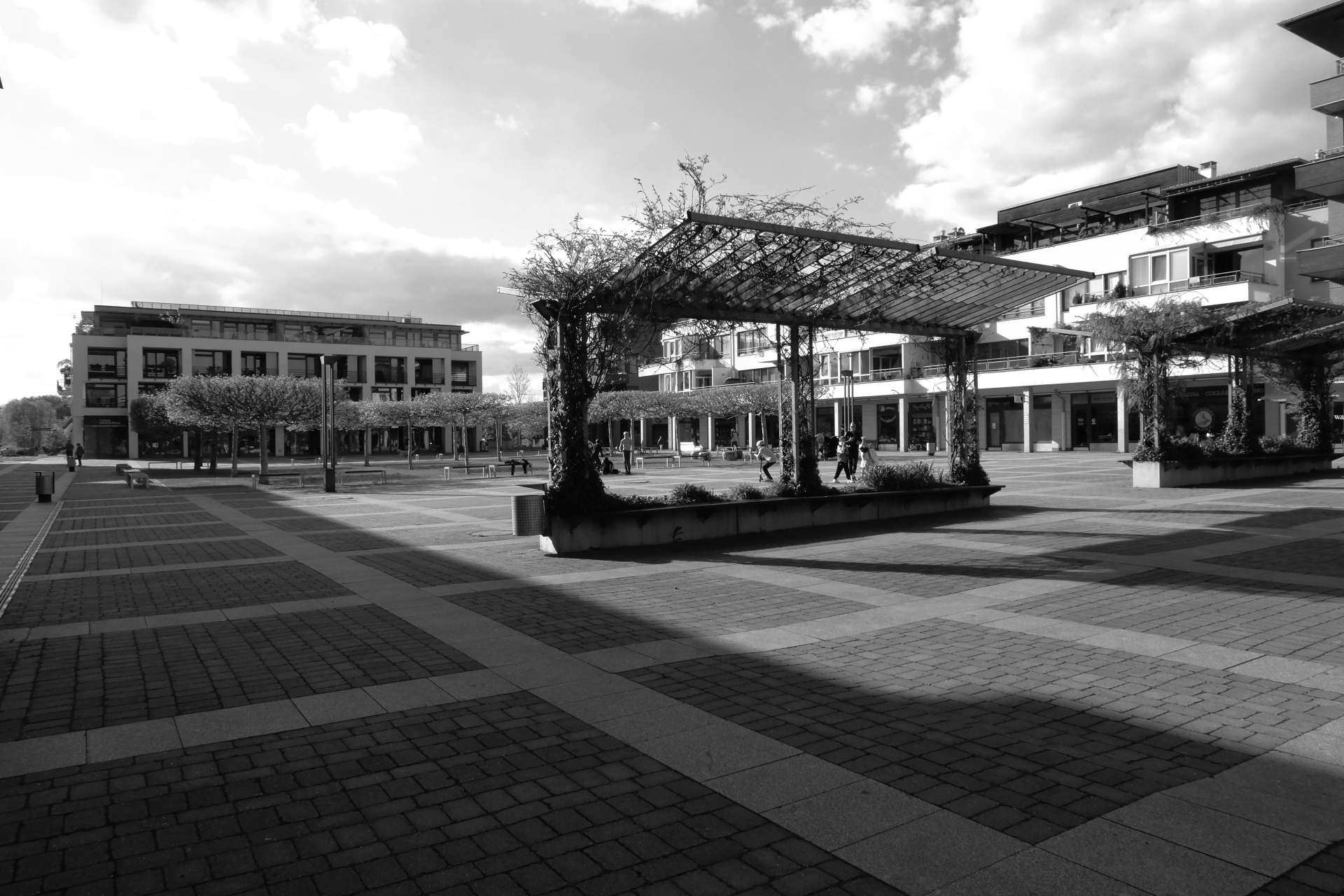

The idea of an actual square began to approach reality in 2006, when the municipality launched an invited competition for the design of a multifunctional town centre, including a square with apartment blocks, on land re-acquired through post-1989 property restitution by the Archbishopric of Prague. The winning project from architects Ladislav Tichý and Václav Dvořák then began to be constructed by the company Centrum Dolní Břežany, founded in 2005 by businessman Jiří Pavlica (75 %), the archbishopric (20 %), and the municipality of Dolní Břežany (5 %). The involvement of the billionaire Pavlica was anything but accidental – he was long known to the mayor from the business world: Michalik was a member of the supervisory boards in Pavlica’s companies ZAPA beton and Highest Investment. For the local government, the investment promised a future share in the income from the rental of commercial space. However, construction proceeded slowly and with notable cost overruns, followed by the economic downturn of 2008, which led the company Centrum Dolní Břežany into bankruptcy. Its primary creditor, the bank Česká spořitelna, eventually sold the foreclosed property. The municipality, though, had already left the company before it went bankrupt, selling its share for the original price back to Pavlica; in turn, the Prague archbishopric was left with an uncollectible debt of 25 million CZK, which it had to write off in 2020, while Pavlica himself claimed to have lost nearly 200 million CZK.39 Despite this economic failure, Dolní Břežany managed to expand in 2010 to include the new square, Náměstí Na sádkách, the adjoining apartment complex, as well as the expansive Celtic and Millers’ Park directly behind the square.

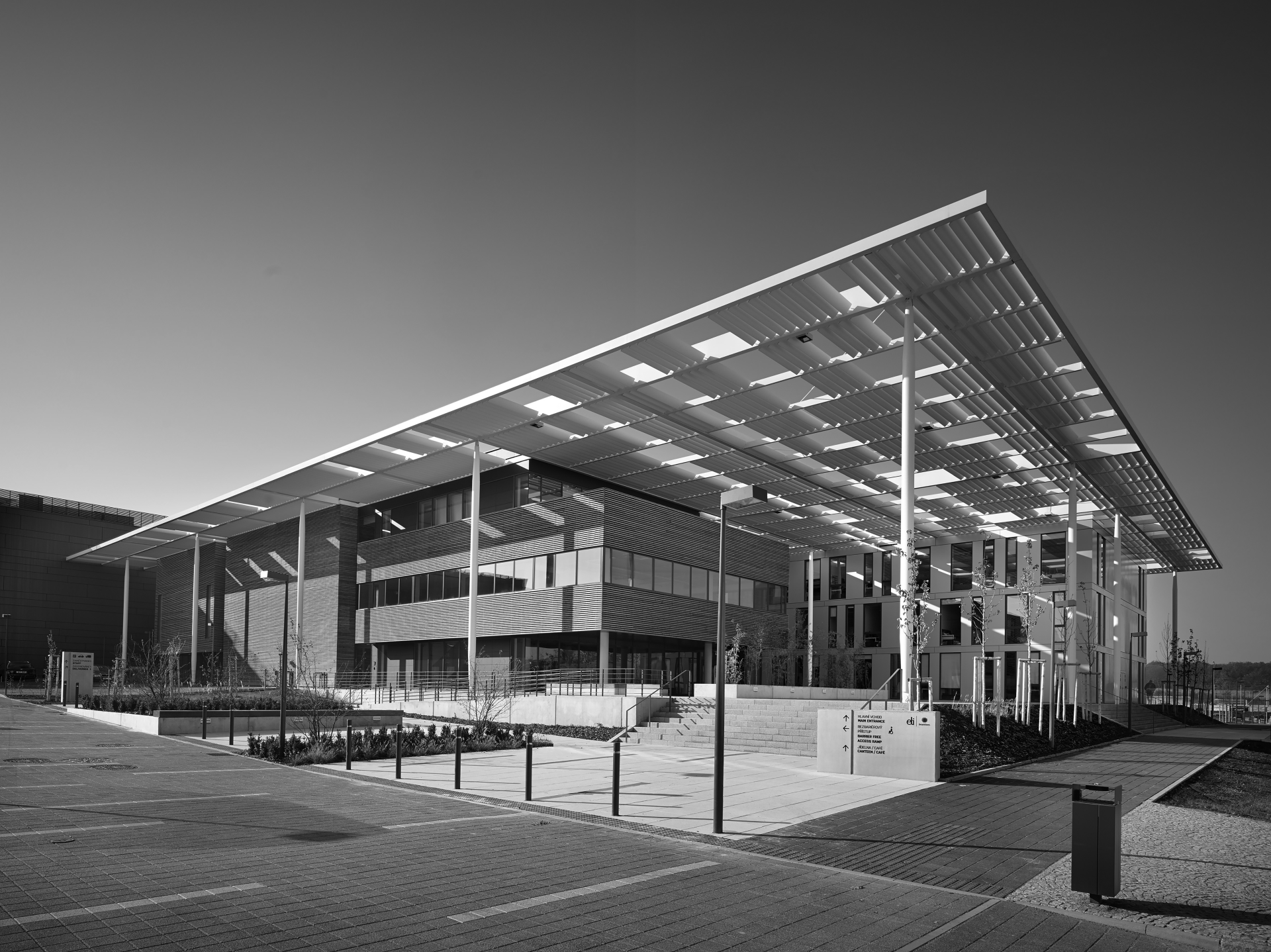

Likewise, the other major development-adventure from Věslav Michalik – the construction of the research centres – took place on the land of the Archbishopric, specifically the site of the agricultural brownfield next to the chateau. To realize his ambitious aims, though, the mayor needed a strong partner, which he initially hoped to find among software firms.40 Eventually, though, he drew upon his personal social capital and offered the land to the Physics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, where he had worked as a researcher in the early 1990s. In 2008, the Physics Institute decided to situate its planned laser centre in Dolní Břežany, a plan that received governmental support. However, the 2009 masterplan still assumed that the land would be set aside for housing construction. Only after several rounds of negotiation between expert commissions, in 2011 the European Union decided to award a subsidy for the construction of the centre ELI Beamlines,41 soon joined by the smaller affiliated project HiLASE, for developing new types of lasers.

ELI Beamlines belongs to the network of the European Centres of Excellence, built from the resources of the European Fund for Regional Development (85 %), specifically the Operational Programme Research and Development for Innovation, and the Czech national budget (15 %). The condition for awarding the support was locating the centre outside of Prague, which because of its high GDP was ineligible under the convergence rules.42 However, several Czech Centres of Excellence, not only ELI in Dolní Břežan but, for instance, the BIOCEV centre for medical research in Vestec, seem to have been planned to find a way around this difficulty – not located within Prague but just beyond the city limits, within the suburban settlement ring. Michalik promised much from the realization of the two centres (both completed in 2015): prestige, new jobs, opportunities for local businesses, growing demand for housing or commercial space. “My assumption is that, over time, we’ll see the emergence of an atmosphere typical for a scientific town: intellectual energy mixed with student insouciance, all in a cosmopolitan spirit of international cooperation” – such was his dream in 2013.43

As in the case of the town square, the municipality first tested the possibilities for the use of the brownfield through student projects at the Faculty of Architecture CTU in Prague. Eventually, a regulatory plan was created by the architect-planners Ivan Plicka and Pavel Hnilička. The site chosen for the research centres lies directly beside the historic village core, with the local office, the chateau, and several preserved farmsteads. It was the mayor’s belief, though, that despite its massive scale, the emerging scientific complex would contribute to “reinforcing the urban structure of the settlement” and that “the resulting effect would shape it into a town”.44 The project for the ELI Beamlines complex was entrusted by the EU scientific commission in charge, Extreme Light Infrastructure, to the British architectural studio BFLS, though later the commission was shifted to the newly founded atelier Bogle Architects, created by a former partner in BFLS, architect Ian Bogle, who had settled in the Czech Republic. At the time, Bogle already had experience from large commercial projects in London, for example the realisation of the residential skyscraper Strata SE1 (then as a partner in Hamilton Architects).45 As such, his portfolio unquestionably suited the scale of the construction project, but somewhat less the spatial location in the historic centre of a small village in Central Bohemia.

Michalik’s imagination of a prestigious “science town” also appealed to the Archbishopric of Prague, which provided the land for the laser centre. Expecting the influx of an affluent clientele, the archbishopric also launched a costly renovation of the chateau into a five-star hotel (Šafer Hájek architekti, interior design Bára Škorpilová, 2018). However, the operation of the hotel proved over the long term a losing proposition, with the archbishopric even considering its sale in 2022. Currently, it has been leased since 2021 to an investment fund.46 Nonetheless, soon after the completion of the ELI Beamlines complex and its neighbour HiLASE, other investments began to follow, such as the company headquarters for Rigaku, a firm developing X-ray machinery (2018) or the Brain for Industry innovation centre (2023). Similarly, the parking garage (Fránek architekti, 2021) would itself probably never have arisen simply in a town of under 5,000 residents. Currently, the Institute of Physics, which runs the HiLASE, is planning another apartment block for construction.

Moreover, during his lifetime Věslav Michalik continued to imagine a future beyond the immediate bounds of Dolní Břežany, a kind of Silicon Valley to Prague’s San Francisco: “It turns out that the trip of land, about six square kilometres in all, between the villages of Dolní Břežany, Hodkovice, and Vestec has good conditions for innovative firms to arrive on a large scale.” 47 In fact, at the edge of Vestec, about 5 km east of ELI Beamlines, there arose from the same EU operational programme another European Centre of Excellence – the biotech research facility BIOCEV. And indeed, this suburban locality has truly ideal conditions for such development – Prague close by, sufficient open land, motorway connections. Basically, alongside the developments of residential and commercial function (logistics terminals, industrial zones, shopping centres), we can see in both Břežany and Vestec indications of an emerging scientific-technological suburbanization.

Between the Countryside, the City, and the Periphery

By way of conclusion, I would now like to draw a comparison between the urban structure of the two settlements, the specific form of the newly created buildings and public spaces, their symbolic and functional levels, their relations to the history of their sites and the surrounding landscape. At present, both villages have different mayors, hence the eras of Martin Kupka in Líbeznice and Věslav Michalik in Dolní Břežany have ended – though the paths they embarked upon will certainly set the directions for the future.

As previously remarked, the key difference between the two settlements is their relation to the idea of the countryside – not in any functional or socioeconomic sense, but to the countryside as a social construction, an imaginary yet largely socially shared image of rurality.48 In other words, the “second rural”, to cite the term introduced in 2007 by the American sociologist Michael Bell.49 In its planning and architecture, Líbeznice turned to the idyll of rurality, the “second rural” yet one that equally brought into itself, bearing in mind the suburban location, an urban mode of life. Dolní Břežany under Věslav Michalik, contrastingly, firmly rejected rurality, all the way from the original vision of a modern small town up to the later ambitions of a global scientific centre spanning the territory of several villages together.

Líbeznice has a fixed centre anchored within the traditional village structure (the concept termed “Three Towers”) and an equally firm construction hierarchy through its height regulation – only public buildings may rise above a certain height level. Newly built public facilities visually adhere to rural forms (the “barn” of the fire station, the “woodstack” of the sports hall), or deliberately retreat into the background beside earlier public buildings (the new school partly sunk into the hillside). The careful landscaping of the public spaces in the historic sections of the village also evoke the idyllic image of rurality, whether through the material used (rough-hewn flagstones, wood) and their handworking, typology (chapel, well), scale, or plantings (fruit trees). Alongside the streets with their reduced traffic volume, the key points in the village (the centre, the school complex, the leisure area, the sports field and hall) are also linked by pedestrian routes leading out into the landscape. Footpaths and tree-belts in the vicinity have been renewed, while further expansion of construction is halted by the outer park-zone and the tree-lined pathways surrounding the entire village.

Everything here is intended primarily for the residents of the village itself and those nearby: the identity of Líbeznice emerges from the continuities with the village’s historic form, from the quality of the architecture and the solidity of the buildings, the care for the public space and the exceptional facilities for education, social and community life, or sports and recreation. Líbeznice is approaching its fulfilment: new private houses and residents will now appear only sporadically, the boundaries for construction are firmly set, yet not to prevent additional internal development and care for the community in the word’s broadest sense. A certain symbolism is present even in the siting of the bus stops, not directly at the important points in the village but always to the side; nearby but only secondary.

Dolní Břežany, contrastingly, displays a strikingly illegible structure of settlement, spreading in several directions at once, with an urban and architectural form that remains deeply heterogeneous and disconnected. The main square, Na Sádkách, created anew on the site of the former village fishpond, formally resembles a traditional square within a block-pattern of construction, i.e., the space left by removing one block of buildings inside a compact urban grid. However, there are no other blocks around the square in Břežany, let alone even a town; what stands here is the town square as stage-set. And many other similar fragments of various structures, deprived of a legible context, are encountered throughout Dolní Břežany. For one telling example, take the shiny metal ellipsoid of the sports hall, which seems literally to have fallen from outer space onto the field behind the school. Equally riven with mutual misunderstanding is the small square behind the local government office: surrounded by original village houses and the restored Renaissance chateau with its chapel, yet also the volumes of the research institutes and innovations centres with their highly corporate aesthetic. In turn, the nearby ELI Beamlines complex entirely exceeds the context in its massive scale. Of course, in many locations we encounter well-cultivated environments, generous public spaces (squares, parks, playgrounds, sports fields), while likewise the architecture of the individual buildings is usually at a very high level. Yet often, these appear as lonely islands that pay no attention to each other, whether in scale or in form and meaning.

Contributing further to this fragmentation is the hypertrophied transport infrastructure: the roads, in some cases without sidewalks, create unpleasant barriers within the village, while the roundabouts in the central area are both spatially demanding and unwelcoming for pedestrians. The parking garage with its façade of aluminium guardrails and the large bus stops, in turn, give the centre of Dolní Břežany the character of a periphery.

In short, the urban design and the architecture of today’s Dolní Břežany represent a hierarchy entirely different from that of Líbeznice. Pride of place and size is not given to public buildings but instead development projects (Na Sádkách or the complex of Pivovarský dvůr directly opposite), global scientific and technological infrastructure, or transport: essentially the aspects expected to entice major investors from outside.

Equally disconnected, if in a different way, is the relationship between the town’s current form and its past. The picturesque section of as Malá Strana is degraded by its cast-concrete paving (unlike the similar locality of U Kola in Líbeznice) and its village green has been swallowed by the roadway. The chateau ground, with the chapel and expansive garden, are closed to the public and watched by security guards. Instead, today’s Břežany has developed such a proclaimed link to its ancient Celtic settlement, symbolised by the oppidum known as Závist, lying within the cadastre of the village. Celtic symbols form the basis for the design of the extensive Celtic and Millers’ Park, lying right behind the square Na Sádkách. Also constructed on the outline of a Celtic cross is the new cemetery, designed by the same landscape architect, which paradoxically lies below the hill of Hradišťátko, where the archaeological finds are not Celtic but the remains of a fortress from the medieval Přemyslid era. And here, among the concentric circles of skilfully constructed stone walls and grassy walkways, the main visual element is the ever-growing number of standard-issue gravestones of polished granite or marble, adorned with plastic flowers.

One surprising finding in comparing the two settlements is the data on commuting for work and schooling from 2021. Even though the research institutes and technology firms in Dolní Břežany provide employment, the overall balance is negative – 422 more people daily leaving Dolní Břežany daily than arriving. Líbeznice, however, has a positive balance: primarily thanks to the large primary school, 119 more people arrive than leave. To be sure, the Líbeznice school system is primarily the destination for children in the nearby villages: considering only the balance of incoming and outgoing commuting between both settlements and Prague, the balance would be equally pronounced for the two – Dolní Břežany minus 693 people, Líbeznice minus 599 people.50

Both mayors, with the aid of urban planners and architects, unquestionably succeeded in creating previously absent public infrastructure for their municipalities, along with cultivating the public spaces and recreational areas. And both made good use of their high (if differently structured) personal cultural and social capital. Hence it is unquestionable that the two mayors significantly improved the positions of Dolní Břežany and Líbeznice in the physical context of Prague’s suburbia and in their standing in the fields of architecture and planning. Evidence is provided, among other sources, in the highly positive media image of both villages (including professional forums) as stellar examples of successful local development. And moreover, neither mayor lost voter support during his long period in office and used their unignorable success in local politics to rise to the regional and later national levels. In fact, after the tragically early death of Věslav Michalik, his name was given to the square between the local government office and the research institutes – as the founding father of “Edge City”51 Dolní Břežany.

Indeed, unlike Líbeznice, where the compact village-form with clear boundaries to new construction is approaching completion, Dolní Břežany remains unfinished: structurally open, hybrid in form and function, yet open to new growth. This same hybrid character fits it well within the anthropocene’s “global city” covering the entire earth, even aspiring to form one of its centres. Whether Michalik’s dreams come true and Dolní Břežany truly merges with nearby Vestec into a belt of scientific and innovation centres or technology firms remains undecided. Equally undecided is the answer to the question of which of these diverging development strategies will prove sustainable for the long term: whether homelike Líbeznice focusing on the quality of life of its residents, or globally ambitious Dolní Břežany alert for every new opportunity.

This paper was supported by the Czech Science

Foundation GA ČR (Grant no. GA 25-17198S).

Mgr. Karolina Jirkalová, PhD.

orcid: 0000-0002-5545-200X

Center for Theoretical Study

Charles University and Czech Academy of Sciences

Husova 4

110 00 Praha 1

Czech Republic

In the Czech case, most thoroughly OUŘEDNÍČEK, Martin, ŠPAČKOVÁ, Petra and NOVÁK Jakub (eds.). 2013. Sub urbs: Krajina, sídla, lidé. Prague: Academia.

HNILIČKA, Pavel. 2005. Sídelní kaše. Brno: Era.

See SKŘIVÁNKOVÁ Lucie, ŠVÁCHA Rostislav, NOVOTNÁ Eva and JIRKALOVÁ Karolina (eds.). 2016. Paneláci 1. Padesát sídlišť v českých zemích. Prague: UPM and SKŘIVÁNKOVÁ Lucie, ŠVÁCHA Rostislav, KOUKALOVÁ Martina and NOVOTNÁ Eva (eds.). 2017. Paneláci 2. Historie sídlišť v českých zemích 1945-1989. Prague: UPM. In English, see SKŘIVÁNKOVÁ, Lucie, ŠVÁCHA Rostislav and LEHKOŽIVOVÁ, Irena. 2017. The Paneláks. Twenty-Five Housing Estates in the Czech Republic. Prague: UPM.

KRATOCHVÍL Petr and MICHALIK Věslav. 2017. Naše požadavky respektují i developeři. In: Novák, A. Česká architektura 2015-2016. Prague: Prostor, pp. 148-153.

In 2023, the local government organised an architectural symposium under this title, which is a variation of the term “the capitol of contemporary architecture” used in connection with the East Bohemian town of Litomyšl. See DOLNÍ BŘEŽANY. 2023. Hlavní obec současné české architektury. Dolní Břežany [online]. Available at: https://www.dolnibrezany.cz/dolni-brezany-hlavni-obec-soucasne-ceske-architektury/d-20743 (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

ŘÍHA Cyril, MEDUNA Petr and VĚTROVCOVÁ Marie. 2020. Globální město aneb Urbanizace bez děr. In: Pokorný, P. and Štorch, D. (eds.). Antropocén. Prague: Academia, pp. 436-473.

I have relied primarily on the main Czech translation of Bourdieu’s writings, BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1998. Teorie jednání. Prague: Karolinum. In English, see BOURDIEU, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In: Richardson, J. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Westport: Greenwood, pp. 241–258.

LÍBEZNCIE. 2025. Místopis. Líbeznice [online]. Available at: www.libeznice.cz/mistopis (Accessed: 24 January 2025); MAPY.COM. 2025. Mapy.com [online]. Available at: www.mapy.com (Accessed: 24 January 2025)

For these images, see GEOPORTÁL. 2025. Geoportál [online]. Available at: https://geoportal.gov.cz/web (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

All data on population developments used in the present text are taken from data compiled by the Czech Statistics Office, see ČESKÝ STATISTICKÝ ÚŘAD. 2024. Český statistický úřad [online]. Available at: https://csu.gov.cz/ (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

ZEMĚMĚŘIČSKÝ ÚŘAD. 2025. Archiv. Zeměměřičský úřad [online]. Available at: https://ags.cuzk.cz/archiv/ (Accessed: 15 February 2025); DOLNÍ BŘEŽANY. 2025. Historie, památky. Dolní Břežany [online]. Available at: https://www.dolnibrezany.cz/historie/ds-1196/p1=16527 (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

GEOPORTÁL. 2025. Geoportál [online]. Available at: https://geoportal.gov.cz/web (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

ČESKÝ STATISTICKÝ ÚŘAD. 2024. Český statistický úřad [online]. Available at: https://csu.gov.cz/ (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

FEŘTOVÁ Marie, ŠPAČKOVÁ Petra and OUŘEDNÍČEK, Martin. 2013. Analýza aktérů a problémových aspektů rozhodování při nakládání s územím v suburbánních obcích. In: Ouředníček, M., Špačková, P. and Novák, J. (eds.). 2013. Sub urbs: Krajina, sídla, lidé. Prague: Academia pp. 234-255. A similar situation can be observed in post-socialist Slovakia, see ŠUŠKA,Pavel and ŠVEDA, Martin. 2023. Let it Sprawl: Post-Socialist Policies Enabling Suburbanization. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 57(3–4), pp. 306–315.

For further evidence, note the oft-cited examples of the development of Litomyšl, Říčany, or even Horažďovice in the 1990s. On Litomyšl itself, see ŘÍHA, Cyril. 2022. The Litomyšl Miracle as an Exemplar of a “Political Thing”. In: Říha C. (ed.). The Rule over your Affairs Once Lost Will Return to You: Architecture and Czech Politics after 1989. Prague: UMPRUM, pp. 362–380.

MARTIN KUPKA. 2025. Kdo jsem. Martin Kupka [online]. Available at: https://martinkupka.eu/kdo-jsem/ (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

TROJAN, František. 2025. Martin Kupka chce pro Spolu 30 procent a volá po změně stylu. Respekt [online]. Available at: https://www.respekt.cz/tydenik/2025/3/martin-kupka-chce-pro-spolu-30-procent-a-vola-po-zmene-stylu (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

IDNES.CZ. 2010. Starosta a bývalý mluvčí vlády Kupka: Premiér neměl radost, že odcházím. idnes.cz [online]. Available at: https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/domaci/starosta-a-byvaly-mluvci-vlady-kupka-premier-nemel-radost-ze-odchazim.A101206_103834_domaci_hv (Accessed: 15 February 2025).

E.g., GEBRIAN, Adam. 2015. Gebrian versus Líbeznice. TV Stream [online]. Available at: https://www.stream.cz/gebrianvs/libeznice-205597#nejnovejsi (Accessed: 15 February 2025); WEHLE, Jiří. 2017. Lidé musí žít spolu, ne vedle sebe, říká starosta Líbeznic, středočeské obce s moderní architekturou. Hospodářské noviny [online]. Available at: https://archiv.hn.cz/c1-65970040-lide-musi-zit-spolu-ne-vedle-sebe (Accessed: 15 February 2025). Líbeznice has been repeatedly discussed on the websites earch.cz and czechdesign.cz along with the printed professional journals ERA 21, Stavba, Architects +, Art Antiques. Líbeznice is also a topic in the publications HECZKOVÁ, Michaela. 2021. Možnosti vesnice, Prague: Meziměsto; DUŠEK, Ondřej and JIRKALOVÁ, Karolina. 2019. K čemu jsou architekti. Prague: Jakost, pp. 116-129 and 186-197.

He first worked as an analyst for the Czech financial institution Živnobanka, then for IB Austria, where he worked his way up to the position of executive director and chair of the board. From 2003 to 2005, he was also a board member of HVB Bank as well as the oversight committee of the Prague Stock Exchange.

See the significant quantity of media sources, including actual links, compiled by Wikipedie: WIKIPEDIE. 2025. Věslav Michalik. Wikipedie [online]. Available at: https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/V%C4%9Bslav_Michalik (Accessed: 2 February 2024).

RYŠAVÁ, Michaela and KLÍMOVÁ, Jana. 2022. Kdo byl Kdo byl Věslav Michalik. Velký profil zesnulého vědce, bankéře a politika, HN [online]. Available at: https://archiv.hn.cz/c1-66995410-zblaznil-ses-to-nikdo-volit-nebude-michalik-vzniku-stan-neveril-nyni-za-hnuti-miri-na-prumysl (Accessed: 2 February 2025).

The candidate lists can be found at ČESKÝ STATISTICKÝ ÚŘAD. 2024. Výsledky voleb a referend. Volby.cz [online]. Available at: https://www.volby.cz/ (Accessed: 2 February 2025).

SHABU, Martin. 2021. Kyperská půjčka pro starostu. Podnikání kandidáta STAN

na ministra opět přilákalo pozornost detektivů. Lidovky [online]. https://www.lidovky.cz/domov/kyperska-pujcka-pro-starostu-podnikani-kandidata-stan-na-ministra-opet-prilakalo-pozornost-detektivu.A211115_100208_ln_domov_vag (Accessed: 10 February 2024); SLONKOVÁ, Sabina. 2021. 50 milionu spojených s Michalikem. Slabé místo Fialova týmu, Neovlivní [online]. Available at: https://neovlivni.cz/50-milionu-spojenych-s-michalikem-slabe-misto-fialova-tymu-2/ (Accessed: 10 February 2024).

See e.g., KUNDRA, Ondřej. 2021. Michalikovo prozření, Respekt [online]. Available at: https://www.respekt.cz/tydenik/2021/48/michalikovo-prozreni (Accessed: 10 February 2024).

Kundra, O., 2021.

SLONKOVÁ, Sabina. 2010. Starosta zmizel z kandidátky TOP09, má v patách policii. Aktuálně.cz [online]. https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/domaci/starosta-zmizel-z-kandidatky-top09-ma-v-patach-policii/r~i:article:667790/ (Accessed: 10 February 2024).

HÁJEK, Ján. 2017. Interview by Karolina Jirkalová, April 2017.

JIRKALOVÁ, Karolina. 2017. A zase ty Líbeznice. Art Antiques, (5), pp. 68-73.

ŠINDELÁŘ, Jan. 2012. Martin Kupka: Malé obce si mohou nechat zdát o investičním rozhodování. E15 [online]. Available at: https://www.e15.cz/rozhovory/martin-kupka-male-obce-si-mohou-ne-chat-zdat-o-investicnim-rozhodovani-734328 (Accessed: 10 February 2024).

LÍBEZNICE. 2011. Integrovaný plán rozvoje obce Líbeznice na období 2011-2014. Líbeznice [online]. Available at: https://www.libeznice.cz/novy-integrovany-plan-rozvoje-obce (Accessed: 12 February 2024).

ČERVÍNOVÁ, Ludmila. 2016. Architekt obci 2016. Líbeznický zpravodaj, 14(10), p. 5 [online]. Available at: https://www.libeznice.cz/sites/default/files/2016/11/lzrijen16web.pdf (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

VAŠOURKOVÁ, Yvette and ŠLAPETOVÁ KOVÁŘOVÁ Anna. 2016. Dolní Břežany: Centrum je důležité kvůli identitě. ERA 21, (4), pp. 27-29.

Vašourková, Y. and Šlapetová Kovářová, A., 2016, pp. 27-29.

DOLNÍ BŘEŽANY. 2013. Strategický plán rozvoje obce Dolní Břežany na období 2004-2013. Dolní Břežany [online]. Available at: https://www.dolnibrezany.cz/vismo/dokumenty2.asp?id_org=2879&id=4069&n=strategicky%2Dplan%2Drozvoje%2Dobce%2Ddolni%2Dbrezany%2Dna%2Dobdobi%2D2004%2D2013&p1=16520 (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

BAŠE, Miroslav. 2004. Proces suburbanizace. In: Baše, M. 2009. Město – suburbie – venkov. Prague: Česká komora architektů, pp. 38-43.

For the 2009 masterplan and all its successive changes, see DOLNÍ BŘEŽANY. 2025. Územní plán 2009. Dolní Břežany [online]. Available at: https://dolnibrezany.cz/uzemni-plan-2009/ds-1328/p1=16806 (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

Vašourková, I. and Šlapetová Kovářová, A., 2016, pp. 27-29.

MOLÁČEK, Jan. 2021. Developer spojený se starostou Michalikem postavil v Břežanech komplex, ale zkrachoval. Obec musí oželet nájemné. Deník N [online]. Available at: https://denikn.cz/753946/developer-spojeny-se-starostou-michalikem-postavil-v-brezanech-komplex-ale-zkrachoval-obec-musi-ozelet-najemne/ (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

JUNGOVÁ, Ivana. 2008. Budoucnost satelitu Dolní Břežany. Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky [online]. Available at: https://mv.gov.cz/webpm/clanek/budoucnost-satelitu-dolni-brezany.aspx (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

ELI BEAMLINES. 2011. Projekt superlaseru ELI dostal zelenou! ELI Beamlines [online]. Available at: https://www.eli-beams.eu/cs/novinky-a-akce/media/projekt-superlaseru-eli-dostal-zelenou/ (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

See the blog post by physicist Jiří Chýla from the Physics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences: CHÝLA, Jiří. 2017. ELI a BIOCEV jako Čapí hnízdo? Atuálně.cz [online]. Available at: https://blog.aktualne.cz/blogy/jiri-chyla.php?itemid=30124, (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

Interview published on the website of the municipality: DOLNÍ BŘEŽANY. 2013. Miliardy pro malou obec. Dolní Břežany [online]. Available at: https://www.dolnibrezany.cz/vismo/dokumenty2.asp?id_org=2879&id=1175&n=miliardy%2Dpro%2Dmalou%2Dobec%2Dbillions%2Dfor%2Da%2Dsmall%2Dmunicipality&p1=16520 (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

DOLNÍ BŘEŽANY. 2013. Miliardy pro malou obec. Dolní Břežany [online]. Available at: https://www.dolnibrezany.cz/vismo/dokumenty2.asp?id_org=2879&id=1175&n=miliardy%2Dpro%2Dmalou%2Dobec%2Dbillions%2Dfor%2Da%2Dsmall%2Dmunicipality&p1=16520 (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

BŘEZINOVÁ, Antonie. 2011. Laserové centrum v Dolních Břežanech. ASB [online]. Available at: https://www.asb-portal.cz/architektura/laserove-centrum-vdolnich-brezanech (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

VODRÁŽKA, Prokop. 2021. Církev ztrátový hotel u Prahy prodávat nebude. Deník N [online]. Available at: https://denikn.cz/552253/cirkev-ztratovy-hotel-u-prahy-prodavat-nebude-projektu-se-ujal-investicni-fond/, (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

HNÍKOVÁ, Eva. 2015. Silicon Valley na dosah Prahy. Ekonom [online]. Available at: https://ekonom.cz/c1-63826010-silicon-valley-na-dosah-prahy (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

HRUŠKA, Vladan. 2014. Proměny přístupů ke konceptualizaci venkovského prostoru v rurálních studiích. Sociologický časopis, 50(4), pp. 581-602.

BELL, Michael. 2007. The Two-ness of Rural Life and the Ends of Rural Scholarship. Journal of Rural Studies, 23(4), pp. 202-415.

ČESKÝ STATISTICKÝ ÚŘAD. 2025. Mobilita. Český statistický úřad [online]. Available at: https://geodata.csu.gov.cz/as/dojizdka/?xmax=1644520.7810039977&ymax=6451490.807388032&xmin=1590954.0672048596&ymin=6422836.246200381&wkid=102100&ds=4&migr=1&dv=20&stream=true&arrow=true&carto=true&tm=23&place=539210&dmin=1&dmax=382 (Accessed 15 February 2025).

GARREAU, Joel. 1991. Edge City. Life on the New Frontier. New York: Doubleday.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.3

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License