Significant changes took place in the urban space of Kraków in the 19th and first half of the 20th century, partly related to the liquidation of the old city fortifications (1806–1815). An oval-shaped park (Planty) was established in place of the demolished medieval fortifications and filled moats in 1815–1834. Then, a circular street was marked out around the new park. In the second half of the 19th century, it acquired a monumental character as a result of the construction of many public buildings.

In 1912, in place of the liquidated Austrian fortifications from the 1860s, construction began of the second city ring. The new circular street, resembling a metropolitan boulevard, was to serve residential and representative functions. This concept was partly related to the Viennese Ring, and in terms of communication to the Viennese Gürtel.

The urban transitions of Kraków in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century were largely determined by military and geostrategic matters. The two most significant urban projects of this era, the Inner Ring (Planty Park) and the Outer Ring (Trzech Wieszczów Avenues),1 which to a large extent still define how the city functions in the present, were created on the sites of former defensive structures that had been dismantled. The aim of this text is to indicate the significance of the demolition of the old city fortifications with respect to the urban transformations of the city. In Kraków, this demolition occurred in two phases, first at the beginning of the 19th century, then at the beginning of the 20th century, each of which influenced fundamental spatial transformations. These projects also contributed to the formation of new districts with different functions.

A significant impact on the form and development of the city came from the continual shifts of which state ruled Kraków during the 19th and the early 20th centuries. Following the third partition of Poland (1795), Kraków was incorporated into Austria. During the war with Napoleon, it was captured in 1809 by the Polish army of the Duchy of Warsaw, and by the provisions of the Peace of Schönbrunn incorporated into the Duchy. In 1813, it came under Russian occupation and, following the provisions of the Congress of Vienna (1815), was made the capital of a semi-sovereign statelet, the Free City of Kraków. In 1831, it was occupied by the Russian army, and in the years 1836–1841 by the Austrian army. As a result of a failed national uprising (1846), the city was again occupied and then incorporated into Austria. It remained within the borders of the Habsburg monarchy until 1918, after which it was returned to a reborn, independent Poland. In the years 1939–1945, the city was occupied by the Third Reich.

Consecutive forced incorporation into different states implied repeated modifications to prevalent political and legal regulations and the city’s geostrategic function, and equally affected the dynamics of its economic and demographic growth. Reflections of this historical tumult were no less evident in urban development processes. As far as European conditions are concerned, Kraków was a medium-sized city. In 1796, it had 22,000 inhabitants, in 1808 it had 27,000, in 1815 it had 23,000, in 1846 43,000, in 1900 – 95,000, in 1914 – 181,000, and in 1939 up to 260,0002.

After occupying Kraków, the Austrian military authorities began plans to convert the city into a modern fortress. The author of three consecutive designs from the years 1796–1798 was Colonel Johann Gabriel Chasteller, who considered making partial use of the city’s medieval walls for this purpose.3 Ultimately, the Court War Council decided that, for financial and political reasons (an ongoing war with France and good neighbourly ties with Russia and Prussia), these plans did not make much sense. Although Kraków was labeled as a fortified location (“feste Platz”), this designation was not followed by specific projects. In this situation, the municipal authorities called for the demolition of the city’s pre-existing fortifications. The fact that the city’s limits were extended due to the formal incorporated of two satellite towns (Kleparz and Kazimierz), alongside several suburbs, was another argument in this case. Such a decision had already been taken in 1792 by the Polish Sejm, but it was only in 1800 that the Austrian authorities began to implement it. In this situation, maintaining archaic fortifications that no longer fulfilled a defensive or policing role became unjustified.4

Emperor Franz I issued a decision to dismantle Kraków’s medieval fortifications in 1804, but due to the outbreak of another war with France (1805) it was postponed until 1806, the year when the demolition works started. The city hall of Kraków, following in part the solutions adopted in Lviv and earlier in Milan, proposed to establish on the site of the demolished walls and moats a city park around the entire Old Town. On the inside, it was to abut existing buildings (tenements, monasteries, churches); on the outside, it would be surrounded by a street that would separate it from the less urbanised suburbs. The implementation of this proposal was delayed by another war with Napoleon’s France and its allies in 1809.

After the incorporation of Kraków into the Duchy of Warsaw, the city hall continued to carry out demolition and clearing works in line with earlier plans. Due to the financial drain of the upkeep of the Polish army, the work was slow. By 1812, the main part of the fortifications had been dismantled and in December 1812, the president of Kraków, Stanisław Zarzecki, presented during a meeting of the Kraków Municipal Council the concept of marking out a circular street around the Old Town. In the spring of 1815 – already under Russian occupation – the establishment began of a city park called Planty, prepared by the builder Jan Drachny. A competing project prepared by entrepreneur Jan Krzyżanowski was rejected.5

After another delay due to the political changes resulting from the Congress of Vienna, the creation of the park was resumed with renewed vigour in 1817. A new project for the establishment of Planty was developed by the architect and senator of the Free City of Kraków, Feliks Radwański. After his death in 1826, further work was directed by senator Florian Straszewski. More systematic work on this investment was ensured through the actions of the President of the Governing Senate (de facto Prime Minister) of the Free City of Kraków, Count Stanislaw Wodzicki, who, as an enthusiastic amateur botanist, supported this project with all his power.6

The initial idea, implemented in the first half of the 19th century, was to create a public park and a circular street planted with trees, of secondary communication importance, which was marked out in the years 1817–1825 on the site of the previously demolished fortifications7. By 1836, most of the work had been completed, with the road circumnavigating the Planty and the Old Town as a pedestrian walkway. However, with the increase in construction activity in the former suburbs from the 1870s onwards, the area began to change its form of use. On the outer side of Planty, the surrounding fabric of small chateaus, manors and detached burghers’ houses became gradually replaced by public buildings and tenements.

In the years 1847–1870, Planty was transformed into a garden with the character of an English park. After 1870, the layout was recomposed and given “educational and patriotic” functions (including the erection of monuments). These last actions were initiated by the presidents of Kraków, Józef Dietl and Mikołaj Zyblikiewicz8.

An increasing monumentality within the development around Planty and the accompanying perimeter street (“Ring”) occurred in the last quarter of the 19th century. Formal buildings were erected on the inner side: the Collegium Novum (main building) of the Jagiellonian University (1883–1887), the Municipal Theatre (1891–1893), the Palace of Arts (1898–1901), and the Higher Theological Seminary (1899–1902). Most projects were built on the inner side: the Fire Department building (1877–1879), the Academy of Fine Arts (1879–1880), the Florianka Insurance Company building (1885), the Main Post Office (1887–1889), the County Governor’s Office (1898–1900), the Chamber of Commerce and Industry building (1904–1906), the Academy of Commerce (1904–1906). Several monumental office buildings erected later, in the interwar period: the Bank of Poland (1921–1925), the nine-storey building of the Feniks Insurance Society (1931–1933) and the Agricultural Bank (1938–1951)9. In addition, a horse-drawn tramway was launched on a small section of the “Ring” in 1882 and an electric tramway in 1901. By 1939, about half of the “Ring” was equipped with tram lines.

The buildings of the Kraków “Ring” corresponded to the stylistic changes in European architecture, and to some extent were a free imitation of the buildings of Vienna’s “Ringstrasse”. Up to around 1900, the monumental buildings were erected in historical revival styles: Gothic Revival and Renaissance Revival, with references to local patterns and earlier centuries10. In the years 1898–1914, certain new buildings were given eclectic and historicist or Art Nouveau facades; after 1918, the latest buildings began to represent various currents of Modernism.

With the monumentalisation of the “Ring’s” development at the end of the 19th century, the street’s use also changed, acquiring significance as a through transit route, an inter-district communication, yet also a symbolic location. After the opening of the railway station (1847), a small section of the “Ring” (up to the medieval Florian’s Gate) began to serve as a formal processional street: the route for the reigning monarchs (Franz Joseph I, Charles I) to enter the city centre, or the bodies of Polish national heroes (Adam Mickiewicz, 1890) to be transported for burial. Starting with the celebrations of the quincentenary anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald (1910), part of the “Ring” increasingly became a venue for political demonstrations and, in the interwar period, for Polish military parades and state ceremonies. Another element that reinforced the symbolic impact of this space for newly independent Poland was the construction of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier right beside the “Ring” in 192511.

The architectural and symbolic transformation of Kraków’s Planty and the circular street around it (the “Ring”) was one of the most interesting examples of use changes in urban space in the 19th century. Interestingly, the role of urban planners in this process was rather minor and secondary to the original idea of establishing a formal city park around the Old Town.

The reincorporation of Kraków into Austria in 1846 had far-reaching consequences for the city. Here, the key decision was the ruling by the State Fortification Commission to designate it as one of the monarchy’s main strategic points, capable of blocking Russian forces on the Warsaw–Vienna operation route and ensuring that Austrian troops could safely mobilise and cross to the north bank of the River Vistula. In this situation, it was decided in 1850 to build a fortified military camp in Kraków, and in 1856, to begin work on a regular fortress12.

In the years 1850–1856, the Wawel royal castle was converted into a citadel and several forts were erected at a distance of around 2–3 km from the market square (Marktplatz), blocking the main roads into the city. After the Crimean War, work began on the construction of a continuous city rampart (“noyau”) of elliptical outline, with bastions and forts at a distance of 1 to 2 km from the market square. Completed completed during the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, it was not long after, following the experience of the Franco-German War (1870–1871) that such fortification systems were confirmed as completely obsolete. As a result, from 1872 onwards, individual forts were erected much further away from the city, and from 1879 (after the Eastern Crisis) the construction of a completely new ring of forts 6–8 km from the city centre began13.

As such, the outdated bastion fortification soon became a burden for the army and the inhabitants of the villages near Kraków. According to the law of the time, for the liquidation and demolition of fortifications, all costs were covered by the military treasury. The Austro-Hungarian army, suffering from a chronic lack of money, was not interested in such a solution and, in consequence, continued to maintain its completely outdated fortifications. However, the years 1886–1887 saw a state railway line built on the defensive embankment (“circumvallation railway”), which enhanced the effectiveness of the city’s southward connection.

It was not until 1904, after the energetic politician Juliusz Leo had assumed the presidency of Kraków, that negotiations began on the future of the archaic fortifications. In the end, the city decided to purchase the western and north-western parts of the fortifications closest to the centre. The north-eastern and eastern parts of the fortifications, less attractive in terms of potential real estate development (among other things, containing a freight depot, a municipal cemetery and the fortress’s logistics facilities) remained in the hands of the army.

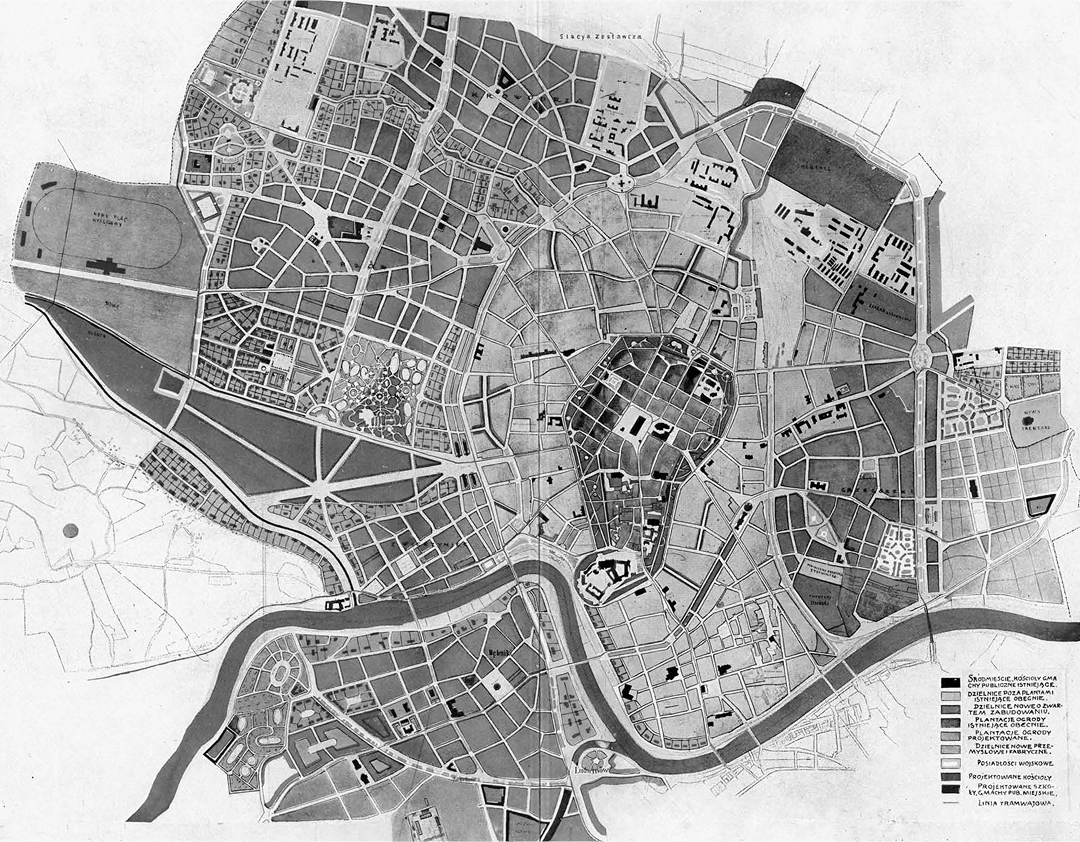

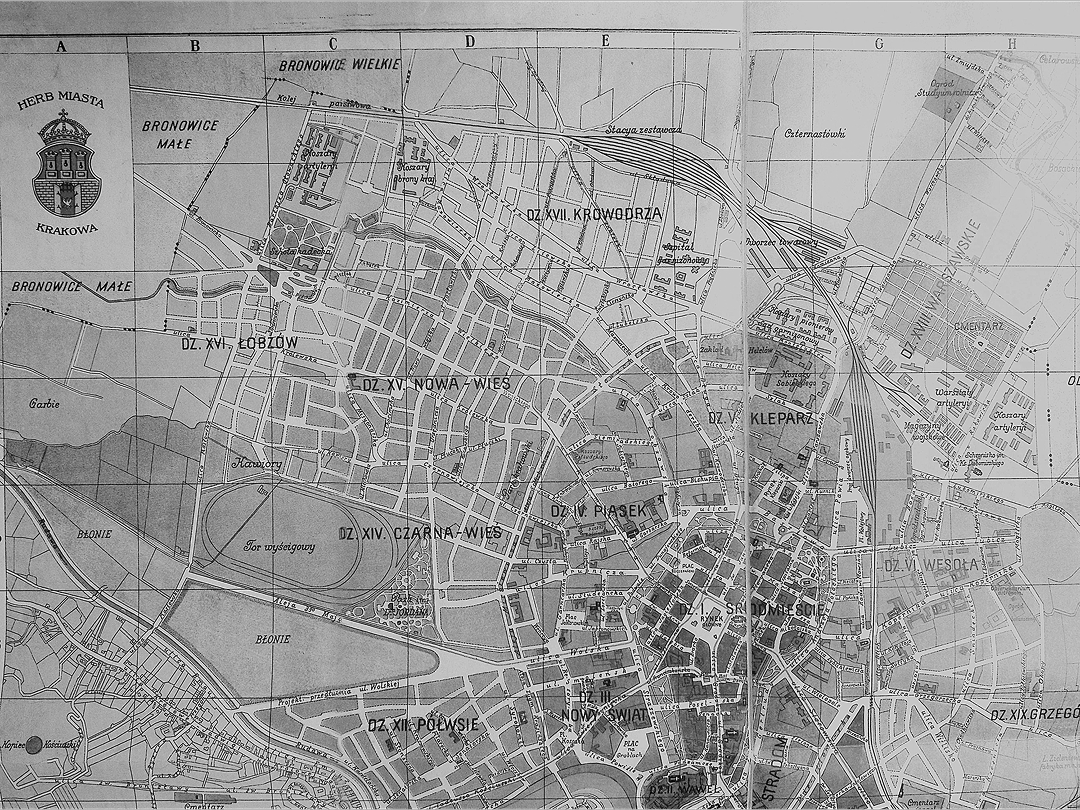

President Juliusz Leo aimed to create a modern metropolis, to be known as “Greater Kraków”. This result was to be achieved by buying up some of the Austrian military areas, incorporating 14 neighbouring municipalities (some of them already urbanised and industrialised) and the satellite city of Podgórze into Kraków, and finally launching an urban planning competition in 1909, an innovation in the Polish context, to design “Greater Kraków” itself. Such plans were also being prepared at the time for other cities such as Berlin, Copenhagen, Canberra and Ghent.14

One of the ideas of the new masterplan was to connect the old development with the new, as well as to reconcile the existing street grid, including the circular traffic (“Ring”) with the newly designed traffic solutions.15 Levelling works (filling the ground) and demolition works (bastions, curtains) were carried out under the supervision of Andrzej Kłeczek. The project of the Commission for Fortress Lands aimed to mark out a perimeter street based on the bypass around Planty. The announced competition for the regulation plan for Greater Kraków was decided on 8 April 1910, with a winning project that assumed the division of the city into functional zones, referring to Ebenezer Howard’s idea of a garden city. One of its elements was to mark out an 80-meter-wide boulevard with the character of a perimeter street from the west and north of the city. Though the plan was not implemented, several of the proposed solutions were used, which also affected the planned perimeter avenue. The concepts of the peripheral boulevard – the second ring – and the overall design of the new districts were partly related to the idea contained in Camillo Sitte’s work “Der Städtbau”, but their implementation deviated quite far from its postulates.16

In 1910, the perimeter railway was removed, while immediately after, in 1910–1911, the City Regulation Office developed designs for a perimeter street, which were approved by the City Council in 1911, establishing its width at 52 meters.17

The result of both the competition and the enacted property solutions was to free up land in the western and north-western parts of the city for development. After the demolition of the former Austrian defences (ramparts and bastions) and the railway line located there, the replacement consisted of a formal avenue with two carriageways separated by a wide green strip (Trzech Wieszczów Avenues), 3 km long (“outer Ring”, “second ring road”), according to a proposal by urban planner Jan Rakowicz. It surrounded the 19th-century urban districts to the west and north.

The implementation of elements of urban projects from 1910 took place in the interwar period. Andrzej Kłeczek, head of the City Regulation Office, played an important role in the implementation of the peripheral avenue. For financial reasons, he limited the width of the new boulevard to about 50 meters, somehow ignoring the increase in car traffic and the potential transit role of the new development. It was not until the investment plan of Kraków from 1937/1938 and the regulatory plan from 1938 that a transit function was foreseen for the avenue (north-south axis).18

The ‘Outer Ring’ was the only large investment directly related to the urban plans of Greater Krakow – indeed, the only investment with a metropolitan character in Kraków during the Second Polish Republic. The architectural form was supervised by the Municipal Construction Office and the Artistic Council, which emphasized the prestigious nature of the investment.19

Even during the initial planning, two monumental public buildings were located along the planned avenue (on the inner side): the Industrial School (1907–1912) and the Collegium Agronomicum of the Jagiellonian University (1905–1912, now the University of Agriculture) in a style reminiscent of historical revival. The 1910 urban plan for “Greater Kraków” envisaged dividing the development along Trzech Wieszczów Avenues into three zones: the southern and northern parts were to be dominated by luxurious residential buildings, while the central part was to have formal and recreational uses. The implementation of these plans was to shift to the interwar period. The new residential development was dominated by four- to five-storey apartment blocks in a Modernist style; their standard was high, attracting as residents the wealthier inhabitants of Kraków (bourgeoisie, officials), both Christian and Jewish. In the formal central part, only the building of the Silesian Theological Seminary (1926–1928) was erected on the inner side, while on the outer side, the following buildings were constructed: the Mining Academy (1924–1935), the Jagiellonian Library (1929–1939) and the National Museum (1933–1939, extended in 1958–1989). In addition, the Silesian House (1931–1937), the Józef Piłsudski House for Physical Education (1931–1934) and the Municipal Touring House (1930–1931) were located in the immediate vicinity of the avenues. All of these buildings were constructed in the Modernist style. Only the oldest building of the Mining Academy received a facade with elements of Classicism.20

The idea of public investments at the outer ring in Kraków was to show the ambition, strength and modernity of the Polish people in the reborn Polish state. Their manifestation in architecture was to be modernism: not only a local specificity, but also extending to many other European countries (Czechoslovakia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland) that had gained independence in 1918.21

These buildings, together with the small Krakowski Park, established back in 1887 in the foreground of the former Austrian fortifications, the nearby Jordana Park from 1889, and a group of education-related buildings (the Queen Wanda Gymnasium, two dormitories) from the years 1924–1937, created a new formal and recreational zone of the city, linked to an elegant circular avenue. The green strip “square” on the Outer Ring was built only in the years 1933-1939.22 According to Jacek Purchla, this proposal was “an echo of the 19th-century concept of the Viennese Ring”.23

This argument is somewhat debatable. In terms of urban planning, Kraków’s “Outer Ring” was more reminiscent of Vienna’s Gürtel. Like its Viennese counterpart, the Kraków project was incomplete: it only covered the western and northern parts of the city, while the Gürtel surrounded Vienna to the south, west and partly north. As in Vienna, the most prestigious buildings (with the exception of Kraków’s National Museum) were located along the city’s inner ring road, on the site of the demolished medieval fortifications. On the other hand, there is no doubt that, in terms of use, the central part of Kraków’s new “Outer Ring” referred to the idea of creating a formal urban block, one such example being the Kaiserforum near the Viennese Ring.

Kraków’s “Outer Ring” project remained incomplete. The Austrian fortress areas in the north-east and east of the city were not demobilised until 1917 and were demolished in the interwar period. Due to a lack of funding and lower attractiveness in terms of development, the city hall decided not to continue the monumental urban layout in the city’s western part. In 1930, only the two-lane Belina-Prażmowskiego Avenue was laid out on the site of part of the former ramparts to the north-east. Its southern extension (Powstania Warszawskiego Avenue) was not built until 1955–1957.24 In fact, the problem of completing the monumental “Outer Ring” on this side of the city was addressed by German planners during the Third Reich’s occupation of Kraków. Hubert Ritter’s designs of 1941 envisaged the establishment of a grand avenue to replace the decommissioned inner-city railway lines of 1847–1856, which were to be moved much further east.25 Nothing ultimately came of these plans.

The design and construction of Kraków’s two circular streets (“Inner Ring” and “Outer Ring”) were the most ambitious urban developments in Kraków in the 19th and early 20th centuries. They contributed to the creation of two new centres of a formal and educational-cultural character, as well as modern areas of residential development. At the same time, they created a new transport and circulation grid that, with some modifications, still functions today. In the 1970s, the “Outer Ring”, and especially the green areas, were degraded in favour of widening the roadway and a sudden increase in motorized through traffic, with a simultaneous decline in park functions26. According to data from spring 2024, the daily traffic volume is 68,000 cars.27 As a result, the green areas of the “Outer Ring” have lost any social and recreational functions.

The specificity of Kraków compared to other Polish cities in the 19th century was that even during the period of its affiliation to Austria (1796–1809 and 1846–1918) and in conditions of incomplete state sovereignty (1809–1846), large urban planning programs concerning circular streets (Ring) could be carried out by Polish architects on behalf of Polish city authorities without the involvement of a national government. On the other hand, the process of granting these avenues a representative and administrative character involved to a large extent, the imitation of the solutions of the imperial capitol Vienna.

These include the German terms from the occupation of Kraków in the years 1939–1945: Ring (Westring, Ostring and Wehrmachtstrasse) as the name of the city’s first ring road and Aussenring as the name of the city’s second ring road; PURCHLA, Jacek (ed.). 2022. Niechciana stołeczność. Architektura i urbanistyka Krakowa w czasie okupacji niemieckiej 1939–1945. Kraków: Wydawnictwo MCK, pp. 36–39.

Calculations based on: BIENIARZÓWNA, Janina and MAŁECKI, Jan M. 1979. Dzieje Krakowa. Kraków w latach 1796–1918. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, pp. 16, 31, 46, 315; ADAMCZYK, Elżbieta. 1997. Społeczność Krakowa i jej życie. In: Bieniarzówna J. and Małecki J. M. (eds.). Dzieje Krakowa. Kraków w l. 1918–1939. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, p. 27.

The first phase of the erection of Kraków’s city walls in the years 1298–1311. After 1338, they were extended to the Wawel castle and then modernised in the between the 15th and 17th centuries. After 1335, construction of the defensive walls of the satellite town of Kazimierz began, and they were completed before 1426. Separate fortifications were built at the Wawel castle (9th–13th century, ca. 1298 to ca. 1346, late 15th century, early 17th century, 1790–1792).

REDEROWA, Danuta. 1958. Studia nad wewnętrznymi dziejami Krakowa porozbiorowego. Zagadnienia urbanistyczne. Rocznik Krakówski, 34(2), pp. 168–171.

BACZKOWSKI, Michał. 2010. W cieniu napoleońskich orłów. Rada Municypalna Krakowa 1810–1815. Kraków: Historia Iagellonica, pp. 110–113, 126–127; Akta Miasta Krakowa, 29/33/0/2.2/3656, p. 915; 29/33/0/2.2/3657, p. 1067; 29/33/0/2.2/3660, pp. 217, 323. National Archive in Kraków; The existing literature on the subject generally ignores the period of conceptual and preparatory work for the establishment of the circular street and Planty in the years 1812–1815, the period when Kraków belonged to the Duchy of Warsaw: RADWAŃSKI, Jan. 1872. Założenie plantacyj Krakówskich, pp. 16–18; TOROWSKA, Joanna. 2012. Planty Krakówskie i ich przestrzeń kulturowa. Kraków: Ośrodek Kultury im. Cypriana K. Norwida, pp. 13–14; KRASNOWOLSKI, Bogusław. 2018. Krakówskie Planty. Zarys dziejów. Kraków: Universitas, pp. 23–34, 85; BUGALSKI, Łukasz. 2020. Planty, promenady, ringi. Śródmiejskie założenia pierścieniowe Gdańska, Poznania, Wrocławia i Krakowa. Gdańsk: Fundacja Terytoria Książki, pp. 268–269.

KLEIN, Franciszek. 1914. Planty Krakówskie. Kraków: Towarzystwo Ochrony m. Krakowa i okolicy, pp. 13–19; Torowska J., 2012, pp. 14–17.

Krasnowolski, B., 2018, p. 85.

Krasnowolski, B., 2018, pp. 119–129; Bugalski, Ł., 2020, pp. 268–269.

Torowska, J., 2012, pp. 26–31; Krasnowolski, B., 2018, pp. 138–145.

DOBROWOLSKI, Tadeusz. 1950. Sztuka Krakowa, Kraków: Wydawnictwo M. Kot, pp. 407–409.

Bugalski, Ł., 2020, p. 270.

WAGNER, Walter. 1987. Die k. (u.) k. Armee – Gliederung und Aufgabestellung. In: Wandruszka, A. and Urbanitsch, P. (eds.). Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918. Die Bewaffnete Macht. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 177–180.

BOGDANOWSKI, Janusz. 1979. Warownie i zieleń twierdzy Kraków. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, pp. 68–120.

KIECKO, Emilia. 2019. Piękno miasta i przestrzenie reprezentacyjne w projektach konkursowych na Wielki Kraków. In: Łupienko, A. and Zabłocka-Koc, A. (eds.). Architektura w mieście, architektura dla miasta. Przestrzeń publiczna w miastach ziem polskich w „długim” dziewiętnastym wieku. Wrocław: Uniwersytet Wrocławski, pp. 189–218; WIŚNIEWSKI, Michał. 2011. Między nowoczesnością i swojskością – konkurs na plan Wielkiego Krakowa oraz Wystawa Architektury i Wnętrz w Otoczeniu Ogrodowym a poszukiwania nowej wizji miasta. In: Małecki, J. M. (ed.). Wielki Kraków. Kraków: Towarzystwo Miłośników Zabytków i Historii Krakowa, pp. 19–34; KLIMAS, Małgorzata, LESIAK-PRZYBYŁ, Bożena and SOKÓŁ, Anna. 2010. Wielki Kraków. Rozszerzenie granic miasta w latach 1910–1915. Wybrane materiały ze zbiorów Archiwum Państwowego w Krakówie. Kraków: Archiwum Państwowe w Krakowie, pp. 283–293.

Architekt. 1910. Program i warunki konkursu na plan regulacji Wielkiego Krakowa. Architekt, 11(6–8), pp. 88, 89.

PURCHLA, Jacek. 2007. Rozwój przestrzenny, urbanistyczny i architektoniczny Krakowa doby autonomii galicyjskiej i II Rzeczpospolitej. In: Wyrozumski, J. (ed.). Kraków. Nowe studia nad rozwojem miasta. Kraków: Towarzystwo Miłośników Historii i Zabytków Krakowa, pp. 637–639.

ZBROJA, Barbara. 2013. Monumentalne i eleganckie – Aleje Trzech Wieszczów. In: Szczerski, A. (ed.). Modernizmy. Architektura nowoczesności w II Rzeczpospolitej. Kraków i województwo Krakówskie. Kraków: Studio wydawnicze DodoEditor, pp. 122–123.

KRASNOWOLSKI, Bogusław. 2011. Realizacja międzywojennego planu Wielkiego Krakowa. In: Bochenek, M. (ed.). Wielki Kraków. Kraków: Towarzystwo Miłośników Zabytków i Historii Krakowa, pp. 67–84.

Zbroja, B., 2013, p. 156.

PURCHLA, Jacek. 1997. Urbanistyka, architektura i budownictwo. In: Bieniarzówna, J. and Małecki, J. M. (eds.). Dzieje Krakowa. Kraków: Wydawnictvo Literackie, pp. 150–151, 162–169; LEŚNIAK-RYCHLAK, Dorota, WIŚNIEWSKI, Michał and KARPIŃSKA, Marta. 2022. Modernizm, socrealizm, socmodernizm, postmodernizm. Przewodnik po architekturze Krakowa XX wieku. Kraków: Instytut Architektury, pp. 164–194.

See: SZCZERSKI, Andrzej. 2010. Modernizacje. Sztuka i architektura w nowych państwach Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 1918–1939. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi.

Zbroja, B., 2013, pp. 155–156.

Purchla, J., 1999, p. 163.

Krasnowolski, B., 2011, pp. 108, 113; WIŚNIEWSKI, Michał. 2011. Między nowoczesnością i swojskością – konkurs na plan Wielkiego Krakowa oraz wystawa architektury i wnętrz w otoczeniu ogrodowym a poszukiwanie nowej wizji miasta. In: Bochenek, M. (ed.). Wielki Kraków. Kraków: Towarzystwo Miłośników Zabytków i Historii Krakowa, pp. 23–24.

Purchla, J., 2022, pp. 77–85.

Bugalski, Ł., 2020, pp. 285–286.

KRAKÓW. 2024. Kraków [online]. Available at: https://www.krakow.pl/aktualnosci/287423,1912,komunikat,na_ktorych_ulicach_w_krakowie_jest_najwieksze_natezenie_ruchu_.html (Accesed: 4 November 2024).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License