The Athenaeum is an architectural genre adopted in the wake of Romania’s extensive and accelerated processes of modernization at the end of the 19th century. Like many other civilizational forms of the West, it was introduced to span the developmental gap after the nation’s long Ottoman rule and emphasize the new direction towards humanistic values and a rational society. However, the Athenaeum did not retain the status of a foreign form but instead launched into motion the forces eager for emancipation and progress of Romania, playing an active role in the decisive stages of affirming its national identity.

Introduction

An interrogation of the enigmatic character surrounding the Athenaeum and the implications that this building type holds in the Romanian cultural space: such a questioning represents the guiding thread of the present study. Whether through objective research into the features and history of its appearance or through the analysis of the implicit subjective perceptions associated with this architectural program, it aims to overturn the many obscurities around the topic.

The theme represents a highly individual episode in the history and theory of architecture, in brief an adventure situated between the inconsistency of the archaeological sources and the speculations that arose from them. However, the time intervals in which the appearances of the Athenaeum were encountered can be easily classified into two characteristic periods for the history of this type of building. On one hand, there is the origin of the Athenaeum in Classical Antiquity, and on the other, its period of recovery, starting with the 17th century, after more than a millennium of absence.

No previous literature has yet to touch upon the evolution of the general architectural phenomenon associated with the Athenaeum, together with its two characteristic hypostases of origin and revival. Although there exist numerous studies that focus either on elucidating the ambiguity of the ancient form, or which aim to present in detail a single modern form of the program, with its specific history and context, the present study focuses on capturing the subsidiary layers of significance that have profound implications for each of the various revival forms, relevant for Romania’s cultural history.

The research method aims to present in brief the theoretical and historical context of the Athenaeum, then to focus on presenting those examples and evolutionary stages assumed in the Romanian space, in direct relation to the cultural and political environment of the respective appearances.

The objective is to present the particularities that this architectural program has acquired in the immediate cultural space of Romania. Therefore, aspects related to the external significance of the Athenaeum are mainly pursued to the detriment of its architectural features or appearance, simply to illustrate the extent to which these meanings end up as decisive (or not) for the affirmation of the cultural and national identities of modern Romania.

A General Historical – Theoretical Context

The architectural program of the Athenaeum is unique in its having a fully documented appearance during Classical Antiquity, through the example of Hadrian’s Athenaeum. Like many other similar ancient programs, it disappeared with the fall of the Roman Empire but underwent a strong revival in its most nuanced forms with the dawn of the Modern Age.

Hadrian’s Athenaeum was a tribute paid by the staunchly Philhellenic emperor Hadrian to the heights of knowledge and civilization established by Ancient Greece. Moreover, this origin is evident simply through the etymology of the name, invoking the city of Athens, the exponent of all these cultural landmarks that influenced the culture of Ancient Rome, but also Western civilization as a whole.

Hence, the Athenaeum’s uniqueness lay not only in its architectural program but equally in its high level of cultural and educational function, essentially assimilated to a form of a forerunner of the modern university.1 In addition to this rather generic definition, based on the mentions in the literary or historical texts of antiquity, otherwise the only source of representation, various other extraordinary ceremonies are recorded in the Athenaeum.

Perhaps the most eloquent depiction of the Athenaeum in an ancient text is that of a liberal school of arts, in the historic sense of the term, dating back to the 4th century, showing Emperor Hadrian’s appetite for such architectural programs and cultural institutions.

“And so Aelius Hadrian, who was more suited for declamation and civil pursuit, established peace in the east and returned to Rome. There, in the fashion of the Greeks or Pompilius Numa, he began to give attention to religious ceremonies, laws, schools and teachers to such an extent, in fact, that he even established a school of liberal arts, called Athenaeum, and celebrated at Rome in the Athenian manner the rites of Ceres and Libera which are called the Eleusinian Mysteries.”2

For well over a millennium, the program fell into eclipse, broadly overlapping with the Middle Ages. The threshold moments of the Athenaeum’s programmatic adventure, of its continuity and discontinuity, are represented on the one hand by the rise of Christianity in Western culture and civilization, with its ambition to purify3 the classical heritage of Antiquity, and on the other hand by the revolutionary ideas of the Enlightenment and the humanistic values they promote, along with the ambition to resettle society on new Cartesian foundations.

To arrive at a truly profound understanding of the Athenaeum, it does not appear sufficient simply to comprehend the sources that were the basis of its late recurrences, the accepted form of an architectural program, as the relationship between specialized spatial configurations and intended activities. A better characterization of the Athenaeum is as a very particular type of building. The symbolic function that generates its metaphorical dimension and drives its forms of recurrence becomes much more important and decisive for its course, whether nurtured by a nostalgic attitude towards the classical heritage or appearing a reactive form linked to the broad social and cultural revolutions conducted under the Enlightenment, in essence the materialization of an ideal in the face of changes that have yet to find a proper answer.

Further, the symbolic function is the only argument for assigning the status of an architectural program to the Athenaeum, considering whether the ancient singularity of Hadrian’s Athenaeum could in fact crystallize into an autonomous typology. Over time, in the absence of material archaeological remains, the very existence of the Athenaeum was the subject of speculation, hypothesized as little more than an abstract concept; its essential idea dismembered into various institutional forms.4

However, more recently the question of the Athenaeum has been raised by new archaeological discoveries in Rome, occurring with the expansion of the C metro line undertaken between 2007 and 2011 in Piazza Venezia. The newly uncovered edifice, of a construction date attributed to the reign of Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century CE, is characterized by a succession of three halls5 to serve as assembly spaces in the urban architectural ensemble of the Imperial Forum, bearing a strong claim to be the genuine physical occurrence of Hadrian’s original Athenaeum. The idea of placing Hadrian’s Athenaeum at the site of the new archaeological discoveries was launched by Roberto Egidi, the archaeologist who supervised the specific site works and who confronted the archaeological data observations regarding the age of the materials with the historical period of the program’s origins.6 Regarding the functional character of the new vestiges, the representative nature has to be underlined, conferred by the location in the proximity of the Imperial Forums where multiple forms of the intellectual and cultural life of Ancient Rome were recorded until the end of the Empire.

In relation to this very first architectural form of the Athenaeum, a distinction should be made during its period of recurrence in between the architectural phenomenon around the Athenaeum and the mere use of its name. Thus, starting from the 17th century onward, we can encounter numerous forms of cultural buildings that continue the ancient line by representing a cultural ideal in the Western civilizational space, yet equally other architectural programs or hybrid functional forms that adopt this name, Athenaeum, only as a demonstration of their elevated standard of activity.

After the 17th century, the term Athenaeum began to be applied to cultural buildings where ideas are debated and exposed, educational institutions, cultural forms of gathering as social practices for the elite, but also for related architectural functions such as museums, libraries, theatres, companies, publications etc.

The proliferation of the Athenaeum since the 17th century as a cultural type of building takes place exclusively in the Western civilizational space, its forms of recurrence responding to the specific needs of the cultural environments where they occur, based on the specific response found by each community to the ideal represented by its metaphor.

The Revival of the Athenaeum in the Romanian Cultural Space

Tracing the evolution of the Athenaeum within the limits of a given national culture becomes increasingly important, as the specific cultural values, national aspirations or historical landmarks of that nation come to define the symbolic function around it. In the Romanian case, the idea became a tool for affirming the nation’s identity during the political reforms undertaken in the process of country’s modernisation initiated in the 19th century.

Regarding the role played by the initial adoption of the Athenaeum program, then its proliferation across Romania’s national territory, the decisive moment for the ideal of national unity is the affiliation of national membership with a much wider cultural space, in this case the space of western civilization. Both from within (via a national inferiority complex) and without (from a developmental standard), the Romanian cultural environment might be seen as a peripheral culture of the West, subsumed by its cultural forms once the direction of development shifted towards rationally based values in the 19th century. The Athenaeum is matched to various historical periods over this course, starting with the war for national independence (1877), the extensive processes of modernization culminating in the first unified national state (1918–1940), followed by the darkness of Communist rule (1945–1989). For this reason, the path and evolution of the Athenaeum in the Romanian space during each of these reference periods will be analysed, tracking back the metabolism of its original meanings, evolving through the changes of the political and implicitly the cultural doctrines of each of these historical intervals.

To assure the relevance of the approach, only a selection of the appearances of the Athenaeum will be used: the ones that present a coherence between architectural form and function to match the lines set by the ancient landmark of Hadrian’s Athenaeum. and not any form of institution that, under the pretext of borrowing the name, wants to mimic the Athenaeum’s role and status.

The Context of Historical Reference for the Evolution of the Athenaeum in Romania

The first historical period of reference for the narrative of the Athenaeum in the Romanian cultural space is linked to the declaration of national independence in 1877 and the Great Union in 1918, when the first and most coherent form of the program represented by the Romanian Athenaeum (the most emblematic building of Bucharest to this day) appeared on the national cultural landscape. Over time, it would become the highest form of educational institution in Romania: a temple of culture and an affirmation of national identity, playing host to countless ceremonies and memorable events of the national history.

The best characterization of this period, as well as the background against which this first appearance of the program occurs, is presented by Titu Maiorescu, a prominent figure for the cultural, social and political life of Romania from the second half of the 19th century. In his theory of forms without substance, he describes the synchronization in Romania’s accelerated modernization processes between the local and the western institutional and cultural forms swiftly implemented across the national territory. His perspective regarding these imports is critical, arguing that the cultural fund of the Romanian people is not yet ready to understand the role of these institutions that remain without a significant impact on the life of the broad mass of the population, but rather the materialization of the whims of a fragile segment of a narrow elite; or in his words forms without substance.

“Before we had a culture that grew beyond the borders of the schools, we created Romanian Athenaeums and cultural associations, and we devalued the spirit of literary societies. Before we had even a shadow of original scientific activity, we created the Romanian Academic Society, with its philological section, its historical-archaeological section and its natural sciences section, and we falsified the idea of the academy. Before we had necessary artists, we created the music conservatory; before we had a single painter of value, we created the school of fine arts; before we had a single dramatic play of merit, we founded the national theatre – and we devalued and falsified all these forms of culture.”7

The Romanian Athenaeum in Bucharest, the first appearance of the institution and one of the many other architectural realizations contributing to Romania’s alignment with Western civilizational values, has through its cultural profile proved over time a closer association with the endeavour for the affirmation of the national identity.

Another very important role that Maiorescu had in the Romanian cultural space during this period, which may have some implications for the deeper reasons behind the appearance of the Romanian Athenaeum, is the development of the first Latin orthography and the initiative for the exposure of the Romance origins of the Romanian language. Although the Latin alphabet had been adopted since 1860, one year after the Union of the Romanian Principalities in 1859, its use was not unanimously respected and it lacked a proper spelling to regulate writing.8 In his 1866 work On the Writing of the Romanian Language [Despre scrierea limbii române], Maiorescu emphasizes the importance of rediscovering the Latin origins of Romanian culture, which in his opinion represent the most important strand of national identity.

From this point of view, the adoption of the program of the Romanian Athenaeum matches the desires to affirming Romania’s Latin origins, whether understood in the full range of humanist values specific to Classical Antiquity that deeply marked the western civilization, or simply through the etymology of its name which explicitly affirms the new cultural orientation sought in the Romanian space.

The second significant period for the adventure of the Athenaeum in Romania begins with the Great Union of Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918, which marks the fulfilment of the ideal of the unified national state as the outcome of the First World War, based on the principle of national self-determination, and ends at the beginning of the communist period. Compared to the crystallized national landmark of the Athenaeum, the period is marked by a proliferation of the program throughout the new state in a derivative form represented by the Popular Athenaeums.

Romanian Athenaeum, Bucharest Photo: Vlad-Răzvan Nicolescu, 2025

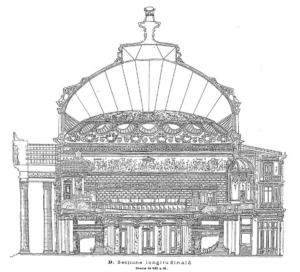

Romanian Athenaeum Source: ODOBESCU, Alexandru I. 1888. Atheneul Român şi clădirile antice cu dom circular. Bucharest: Socecu und Teclu, p. 67

These Popular Athenaeums constituted one of the instruments for consolidating national awareness, along with the attempt to emancipate society through extensive educational reform. Unlike other similar cultural or educational architectural programs, the Popular Athenaeums were, uniquely, the fruit of private initiatives in the context of liberal policies, though relying nonetheless on state support.

Regarding the parallel between the adoption of the Athenaeum in the Romanian space and the identity of Latinity as the origin of national culture and the ethnogenesis of the Romanian people, a fundamental distinction must be noted: the significantly greater appearance of the Athenaeum in the historically united provinces of Wallachia and Moldova, against the much lesser occurrence in the heterogeneous society of Transylvania.

In other words, the interwar period in Romania is characterized by a cultural and educational offensive aimed at solving the inherent crises caused by fundamental changes in the organization of the state, translated as a way of national unification through culture by connecting the educational systems of the old historical provinces.9

The communist period involves the state suppression of these Popular Athenaeums, manifested by the censorship of any cultural and social manifestation. Rejection of the values previously considered decadent by the doctrine of the new regime affected even the Romanian Athenaeum itself, regarded as the chief exponent of Romanian culture but reduced to a mere historical landmark meant to condense the identity of the Romanian people into a single image.

Currently, in contrast to Romanian Athenaeum, not only important as a cultural institution in the national context but equally the architectural image of the city of Bucharest, only a few of the Popular Athenaeums have survived, and of these very few with uninterrupted activity. The phenomenon that thus marks the programmatic adventure of the Athenaeum in Romania seems to be generalized at the level of Western civilization, through the apparently outdated character around it based on the cultural ideals projected over the past by almost every regional cultural environment.

The Romanian Athenaeum

The Romanian Athenaeum represents the first and most important appearance of the institution’s architectural program in the Romanian cultural space. Its iconicity arises both from the remarkable architectural expression within the urban space of the capital, displaying numerous symbols that refer to the vein of national identity, but also due to the representativeness of the building as the locus for repeated events of cultural or historical importance.

The Romanian Athenaeum Society [Societatea Ateneul Român] was founded in Bucharest in 1865, as an organization where subjects related to science, art or literature could be debated by the specialised academic community, or even other persons or societies aiming to deepen the understanding of topics of common interest. As such, the Athenaeum became an instrument of social dialogue between the thin stratum of intellectuals and the public.10

It is worth noting that the year of establishment of the Athenaeum Society, still without a headquarters purpose-built to its specific needs, is very soon after the political achievement of the Union of the Romanian Principalities in 1859, in the wake of the extensive modernization that characterised this period. Cultural or scientific gatherings held within the Athenaeum occurred in a spirit of re-evaluating and resetting the nation’s cultural values, to reorient them from Ottoman influence towards the Western cultural space. The intellectuals of this period assumed the nation to have fallen significantly behind Western Europe, trying to understand the causes of this delay but also displaying initiative to overcome gaps through the adoption of forms like the Athenaeum. Predictably, the attitudes to the reformist endeavours were themselves challenged, with the most important directions split between the traditionalists and the deep reformists. National progress and modernization thus lay between these two positions, reconciling the adoption and rapid integration of these Western forms of civilization to the extant cultural profile of the Romanian people. Similar to the trends in the interwar period, hoping to consolidate national sentiment after achieving the ideal of bringing all Romanians into a single state, in the period preceding it, the role of those incoming cultural forms aimed to unite the Romanians through culture, yet equally serving as tools for the dissemination of these cultural ideals to which the whole nation aspired.11

Regarding the spatial configuration and architectural expression of the current headquarters of the Romanian Athenaeum, construction began in 1886 according to the plans of the French architect Albert Galleron. It is important to specify that the striking circular shape of the main hall was dictated by the presence on the site of earlier foundations intended for the Romanian Equestrian Society. In this way, the architect had the difficult task of adapting the new project to the footprint of the existing masonry. The solution adopted was to place the large hall of the Athenaeum above the access vestibule, as their arrangement in direct succession would not be possible in the set perimeter of the edifice. The Athenaeum building underwent further expansion; the new wing housing the monumental staircase was meant to host the State Art Gallery.12

Stylistically, the Romanian Athenaeum building uses neoclassical elements. The primary application is the access portal with its eight columns, six frontal and two lateral, recalling composition of the ancient classical temples. Among these fragments of architectural language, a special feature is the decorative inscriptions of the names of personalities important for Romanian or European culture and history.

The building of the Romanian Athenaeum underlines the vision of Constantin Esarcu, the leader of the society, who precisely stated the new edifice’s proposed role:

“Choosing a central place so that the building is worthy of its destination, not a vulgar and petty edifice. Let us assume the ambition to build in Bucharest a palace of sciences and arts, where we can proudly welcome the celebrities who will visit us or be invited to our country.”13

Romanian Athenaeum, Bucharest Source: author’s personal archive, 2025

One important aspect to be noted in the Romanian Athenaeum is its artistic decor, with elements that strive to accentuate national identity and history. Among the representations that deal with prominent national personalities or important events, the circular frieze in the great hall ranks among the most important elements: depicting 25 representative scenes of national history from the ancient past and the Daco-Roman wars up to the period of the 19th-century kingdom and state consolidation.14

Another key element associating Romania’s historical episodes or personalities with the headquarters of the Romanian Athenaeum is situated in the access portal of the main façade. Five medallions rendered in mosaic depict the five great leaders of the Romanians from the united historical provinces: two from Moldova, two from Wallachia, and in the middle is King Carol I, already the ruler of the Kingdom of Romania after the union.15

Probably one of the most decisive events for national history hosted by the Romanian Athenaeum, contributing enormously to the consolidation of Romanian identity, was the establishment of the first parliamentary assembly of the united provinces, which on 29 December 1919 validated the act of unifying Bessarabia, Bucovina and Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania. In this way, the most important event of national history happened to occur on the premises of the Romanian Athenaeum, thus further enriching the building’s legacy of national symbolism.

To be sure, it was largely by accident that the Romanian Athenaeum became the temporary headquarters for the first parliamentary assembly of Greater Romania (the colloquial name of Romania after the World War I – involving the largest expansion of territory after the union with Transylvania): the Palace of the Assembly of Deputies was under renovation at the time. However, the event itself formed a tribute to the symbolism in which identity issues and the new status of the unitary national state were debated at length.

One curious observation, though, is the striking similarity between the dome of the Palace of the Assembly of Deputies, currently the Patriarchate Palace, built in 1907 under the guidance of architect Dimitrie Maimarolu, and the dome of the Romanian Athenaeum. However, departure from the ecclesiastical surroundings and its associated symbolism once again emphasizes the humanist metaphor expressed by the Athenaeum.

Although the example of the Romanian Athenaeum represents an exemplary case of an external form metabolized by a national culture, moreover so completely integrated into its identity as to represent the highest national cultural landmark, there have been many criticisms of its failure to achieve its original mission: facilitating access to culture and knowledge for the broad mass of people. This role was to be taken over by the Popular Athenaeums in the interwar period, offering a tailor-made response to the needs and specific regional culture throughout the new national state characterized by striking ethnic heterogeneity, especially in the historical province of Transylvania.

The Popular Athenaeums in the Interwar Period and Their Status in Transylvania

The unique form of the Popular Athenaeums across interwar Romania’s territory follow the path traced by the cultural phenomenon represented by the Romanian Athenaeum in Bucharest. However, the reputation that this typology acquired among the masses emerges less from the uniqueness of its forms, although remarkable examples among the Popular Athenaeums emerged and survive to this day, but more the subtle connection of their responses to regional cultural needs.

The Popular Athenaeum arose out of the Athenaeum as a generic form, assuming precisely the mission to which the Romanian Athenaeum failed to fully respond: becoming an instrument of democratization and knowledge-dissemination among the Romanian people throughout the united territory of Romania, caught in the grip of extensive nationalization policies applied through culture and education.

“The University and the Academy: these institutions serve the same purpose, but they lack precisely the quality that must be the target of the activity of the Athenaeum: direct and permanent contact with the general public. I have been convinced of the importance of this activity since the beginning of my scientific career.”16

The offensive of nationalization from the reunified state should not be seen as a question of economic processes to threaten the property rights or status of certain ethnic groups, but as a coordinated offensive to use state policies to raise and strengthen the civic consciousness of the population, social emancipation through culture, yet also the enrichment of the new national status both domestically and internationally. All members of the national and linguistic communities were invited to take part in the activities and cultural life of the Popular Athenaeums, without any layer of cultural elitism, against the common criticism for the many Popular Athenaeums ridiculed over time for the subversive activities promoted in their bosom, together with the propaganda of authoritarian regimes or the promotion of cheap entertainment. The development attitudes cultivated in the Popular Athenaeums represent another point of interest, as they strive to outline the profile of responsible citizens who manage to achieve a level of balance between their own needs and aspirations, family life and public exposure.17

As for the acceptance of the Popular Athenaeum in Romania’s various provinces, greater receptivity is evident in the extra-Carpathian space of the Old Kingdom, in contrast to the newly annexed provinces. Most likely, this fact is due to the significantly greater homogeneity of the social structures in the extra-Carpathian areas. In addition, there is a probability that some ethnic communities, especially from Transylvania, perceived this variation of the Popular Athenaeum as a branch of the central Romanian Athenaeum, and therefore the adoption of the Popular Athenaeum at the local level might appear as capitulation, even from a cultural perspective, towards the central authority.

Romanian Athenaeum, Bucharest Photo: Vlad-Răzvan Nicolescu, 2025

Patriarchate Palace, former Palace of the Assembly of Deputies Photo: Vlad-Răzvan Nicolescu, 2025

The first Popular Athenaeums appeared shortly after the Great Union of 1918, the first of them founded in Iași in 1919, a city known not only for its historical and economic importance, but also as the informal cultural capital of the province of Moldova. In the national capital Bucharest, although the number of Popular Athenaeums ends up being considerably higher, they began to appear only from 1924.18

From the administrative point of view, the Popular Athenaeums represented forms of private initiative, in their founding as much as their management. Though operated with the involvement or encouragement of the relevant state institutions, their resources were provided by the members through contributions or by various economic activities. In this case, the need for an active economic life connected to the individual athenaeum’s location became mandatory to ensure the sustainability of the program. The Popular Athenaeums are found mainly in an urban environment, although many of them nurture ethnographic concerns mainly related to rural life.19

In Transylvania, very few instances of Popular Athenaeums are recorded, most of them being territorial subsidiaries of the Romanian Athenaeum. However, there is a precursor in the Romanian community before 1918, the so-called National Houses, defined as cultural settlements that had the function of ensuring the connection with the Country (Kingdom of Romania) beyond the Carpathians and which evolve in certain particular cases in the forms of Popular Athenaeums.

“In Pârneava, the National House founded a quarter of a century ago on the initiative of the great forerunners: Dr. S. Oncu, the director of the Victoria bank and the editor of the People’s Tribune Ioan Rusu-Șirianu, received a regenerating boost during 1927 through the establishment of the Popular Athenaeum, which aims to realize today, all over Romania, the ideal of the great founders of the former National House. The Athenaeum’s rise into the leading communes from the country’s border are achievements started from the mysterious inspiration of the Arada generation a quarter of a century ago, which in 1902 allowed the Romanian sentinel to be painted on the curtain in the great hall. …”20

During the same period preceding the First World War, the name Athenaeum appears in Transylvania in a reactionary manner, where the very name accentuated the Latin strand in the identity of the Romanian community. In 19th century Transylvania, multiple Romanian citizen organizations and initiatives fought for the right to education in the Romanian language, its cultivation and representation in administrative matters.

Popular Athenaeum – Iași Source: CLOȘCĂ, Constantin. 2002. Puterea culturii Ateneul Tătărași (1919–2002). Iași: Editura Alfa

For Transylvania, perhaps the earliest appearance of the name of the Athenaeum dates to the first half of the 19th century, the Preparadia in Arad, an institution responsible for the training of teachers and priests in the western part of the region, still under Habsburg rule. Here, it was meant to establish a printing house for the works and manuals in Romanian, but due to the lack of finances, it was decided to establish a collection of manuscripts in Romanian intended to be published later on, under the title of The Athenaeum of Knowledge, the Cabinet of Romanian Muses.21

If the Romanian Athenaeum represents the success of fusing an international program to the cultural profile of the Romanians, remaining a relevant landmark and consolidating its status as a temple of Romanian culture over time, the Popular Athenaeums show that the vitality of the Athenaeum program need not be only an imported recipe, but an active metabolism capable of facing the social and cultural changes that Romania has gone through over the last two centuries.

The Athenaeum of the Present in Romania

The phenomenon of adoption and metamorphosis has faded, no longer relating to the needs and specific cultural profiles within the national territory. As such, it follows the trajectory that the Athenaeum encounters internationally. The initiative to conceive an Athenaeum today, understood in all its complexity of meaning, seems outdated yet somehow natural at the same time. If its recurrent forms aimed at re-evaluating and resuscitating a classical ideal on the same scale, the present’s relationship to the past and to its architectural forms that have passed the test of time, thus becoming classical, is one of contemplation.

Starting with the establishment of Communist rule in Romania immediately after the end of World War II, no new Athenaeums appeared in its territory. Those few forms of the program that survived the censorship or cultural mutilations of this time interval become significant cultural landmarks of the present, both locally, regionally and nationally. They also remain a testimony to the decisive role that the institution held in key periods for modern Romanian history.

Under the communist regime, numerous other cultural or educational building types developed, such as the House of Culture [Casa de cultură], in the larger towns or cities, or Home of Culture [Cămin cultural], mainly in the countryside. The main function of these should be understood as an instrument for political propaganda or entertainment. Cultural gatherings were strictly supervised by the authorities, hence such a cultural-architectural institution as the Athenaeum, regarded in its full nuances of meaning, became eradicated from the public sphere.

Yet nonetheless, today the importance of education and culture seems more important than ever for the destinies of the countries in this part of Europe, when the fervour of the nationalistic spirit is frequently used as a weapon of manipulation to serve obscure interests. The Athenaeum may appear an initiative of the past, whether in Romania or worldwide, but locally, such examples as the Romanian Athenaeum in Bucharest represent the highest national cultural authority. In Romania, the lesson provided by the humanistic values preached by the Athenaeum does not inhibit but indeed creates the background on which the national identity profile takes shape, by enhancing its original fibre through education and culture.

Notes

1 SMITH, William. 1875. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray; LÓPEZ GARCIA. Antonio. 2015. Los Auditoria de Adriano y el Athenaeum de Roma. Florence: Firenze University Press.

2 AURELIUS, Victor. 1994. Aurelius Victor: De Caesaribus. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, p. 16.

3 During early Christianity, ancient literature and culture in general were considered full of sinful, heretical, idolatrous, tempting, and the theological writings of that time were unshakable in this regard. In the Apostolic Constitutions, a collection of eight books from the 4th century AD, describing Christian moral and orderly conduct, a chapter of the very first book is dedicated to the fading authority of the classical works for Christians: “Beware of all pagan books!”. NIXEY, Catherine. 2019. Epoca întunecării. Cum a distrus creștinismul lumea clasică. Bucharest: Humanitas, p. 179.

4 MARROU, Henri-Irénée. 1932. La vie intellectuelle au forum de Trajan et au forum d’Auguste. Mélanges de l’école française de Rome, 49, pp. 93–110.

5 Only two of the three halls can be described as a new discovery, as the traces of one were discovered one hundred years earlier. Of the three, only the features of the middle one are entirely preserved, and their extrapolation into the entire spatial sequence represents a tool for various scenarios of use. Access to the interior of this edifice is placed through a portico facing Trajan’s Forum, the most important component of the Imperial Forums complex and another indication of the representative character of Hadrian’s supposed Athenaeum, but also of its importance for the cultural life of Ancient Rome. The connection between the portico element and the hall space is mediated by a corridor with the role of a buffer space, believed to have been reserved for the orators as a preparation space before lectures or a location for critical debates and informal social interaction. EGIDI, Roberto and ORLANDI, Silvia. 2011. Una nuova iscrizione monumentale dagli scavi di piazza Madonna di Loreto. Historika, 1(1), p. 301.

6 LÓPEZ GARCIA, Antonio. 2015. Una revisión de las fuentes históricas que mencionan el Athenaeum de Roma. Habis, 46, p. 264.

7 MAIORESCU, Titu. 1868. În contra direcției de astăzi în cultura română. Convorbiri literare, (19). „Înainte de a avea o cultură crescută peste marginile școalelor, am făcut atenee române și asociațiuni de cultură și am deprețiat spiritul de societăți literare. Înainte de a avea o umbră măcar de activitate științifică originală, am făcut Societatea academică română, cu secțiunea filologică, cu secțiunea istorico-archeologică și cu secțiunea științelor naturale, și am falsificat ideea academiei. Înainte de a avea artiști trebuincioși, am făcut conservatorul de muzică; înainte de a avea un singur pictor de valoare, am făcut școala de bele-arte; înainte de a avea o singură piesă dramatică de merit, am fundat teatrul național – și am deprețiat și falsificat toate aceste forme de cultură.” [translation of the author].

8 ACOMZEI, Constantin. 2018. 100 de ani de grafie românească. Iași: Asachiana, pp. 5–9.

9 LIVEZEANU, Irina. 1998. Cultură și naționalism în România Mare. Bucharest: Humanitas, p. 45.

10 Anuarul Ateneului Român pe anii 1902–1903 și 1903–1904. 1904. Bucharest: Tipografia Curții Regale, p. 40.

11 ADAMESCU, Gheorghe. 1931. Ateneul Român. Boabe de grâu, 2(3), p. 138.

12 Adamescu, Gh., 1931, pp. 144–145.

13 TEIUȘAN, Ilie Popescu. 1968. Ateneul Român. Iași: Meridiane, p. 23. „Alegerea unui loc central, încât clădirea să fie demnă de destinația ei, nu un edificiu vulgar și meschin. Să avem ambiția a construi în București un palat al științelor și al artelor, în care să putem primi cu mândrie celebritățile ce ne vor vizita sau le vom chema în țara noastră.” [translation of the author].

14 CERCEL, Elena. 2012. Marea frescă de la Ateneul Român – Creația pictorului Costin Petrescu. NOEMA, 11, p. 485.

15 Cercel, E., 2012, p. 486.

16 Din publicațiile Ateneului N. Iorga, Doi ani de activitate, 1926–1928, p. 11 apud. DAICHE, Petre. 1969. Ateneele populare din București și rolul lor în culturalizarea maselor (1918–1944). București – Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, 7, pp. 123–140. „Universitatea şi Academia, instituţiile ce servesc au acelaşi scop ca şi dvs., dar le lipsesc tocmai calitatea care trebuie mai ales să fie ţinta activităţii ateneului: contactul direct şi permanent cu marele public. Despre importanţa acestei activităţi, sînt convins de la începutul carierii mele ştiinţifice.” [translation of the author].

17 CASTRIȘANU, Teodor. 1927. Ateneul Popular. Cultura poporului, (199).

18 CLOȘCĂ, Constantin. 2002. Puterea culturii Ateneul Tătărași (1919–2002). Iași: Editura Alfa, p. 34.

19 Cloșcă, C., 1927.

20 Tribuna Nouă. 1929. Tribuna Nouă, 6(11), p. 1. „În Pârneava Casa Națională fondată înainte cu un sfert de veac din inițiativa marilor înaintași: Dr. S. Oncu, directorul băncii Victoria și redactorul Tribunei Poporului Ioan Rusu-Șirianu, a primit în cursul anului 1927 un avânt regenerator prin înființarea Ateneului Popular ce tinde să realizeze azi în România întregită, idealul marilor întemeietori ai Casei Naționale de odinioară. Descinderile Ateneului în comunele fruntașe dela frontiera țării sunt realizări pornite din tainica inspirație a generației arădene din nainte cu un sfert de veac, care pe cortina din sala mare a lăsat să se zugrăvească, în anul 1902 sentinela română. …” [translation by the author].

21 SINACI, Doru. 2021. Pledoarie pentru Ateneu în Ateneu Arădean. Revistă de cultură, (2), pp. 7–9.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.1

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License