The paper investigates three projects of the Hungarian state design firm BUVÁTI: the Inner-City Shopping Centre, the Fontana department store and the Kígyó Passage, interpreting these works as mock-ups of capitalism, where a socialist society could practice and act out consumerism. Designed and built to converge towards a part-imagined West, these phantasmagorical visions of capitalism from the eastern perspective nonetheless proved to be unfitting after the regime change. The shedding of a socialist Eastern European identity and the immersion in a new capitalist identity demanded a change in the architectural setting, here depicted on the sociocultural, economic and architectural levels.

“The freedom of scarcity has ended,

let the tyranny of abundance begin.” 1

Within the slowly establishing architectural coulisses of capitalism gradually emerging in the last years of Goulash Communism, East-European societies were training to act out consumerism. Yet the shops and the products on display, the architectures, were not yet convincing, only mere mock-ups of capitalism, a peculiar East-European fantasy of the West. This article argues that the analysed projects of the state planning firm BUVÁTI2 – the Inner-City Shopping Centre on an urbanistic scale, the Fontana department store and the Kígyó Passage on an architectural scale – can be placed on this very threshold between late socialist modernism and early capitalist realism, which contributes to their ambiguous character and hindered their integration into the to be established smooth streetscape of neoliberalism.

Consumerism was exercised in this coulisse, however real existing capitalism, to borrow late British cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s terminology3, demanded a different, much more convincing stage-set for the performance of genuine capitalism after the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989/1990. Unrestrained and unregulated, privatisation and market-driven real estate speculation radically reshaped the streetscape and cityscape of inner Budapest. Here, the greatest casualties were nearly all the remnants of socialist late-modernist architecture, even including the architecture purpose-designed and built to converge towards Western consumerism. Within this process, we can cite not only the demolition in 2022 of the Fontana department store, a remarkable example of socialist late-modernist architecture, but also the removal or at best fragmentation of the attempt and vision by architects Miklós Kapsza, József Schall and György Vedres and the team of the state planning firm BUVÁTI to establish a passage system of connecting courtyards, following the organic development of late 19th-early 20th century urbanism.

Consequently, the shedding of an Eastern European identity and the full immersion in a new capitalist identity demanded change of the architectural setting: from an anticipatory Eastern European vision – one might even say phantasmagoria – of Western capitalism to a market-driven investor architecture of speculation where architecture is replaced by real estate. Now, the building plot and the built rented space is economically more valuable than the architectural form and solution, which in turn must ensure the strict maximisation of utilisable and marketable space of the plot and the building. Hence, what can be observed in the investigated examples is the (ex)change of a socialist, Eastern-European identity with a consumer capitalist identity on a socio-cultural level (a), echoed the replacement of late-modernist buildings erected during socialism with capitalist investor developments on an architectural level (b), again in direct relation with the building plot and the marketable and rentable space becoming more valuable than the building itself on an economic level (c). Overall, this model can be placed within the framework of the “overt demonstration of capitalist potency”4, whereby the privatisation and abandonment of public space (the closing of commercial passagess, consequently the reduction of porosity and permeability of the urban blocks as well as the surveillance of public space) is, according to Mark Fisher, “celebrated” by neoliberalism5.

“Socialist” Spatialities in the City Centre of Budapest: Between Demolition and Neoliberalist Transformation

Three projects by György Vedres, then chief architect of the state planning firm BUVÁTI, are analysed as case studies. Formerly situated in the urban core and locus of economic and tourist activity of Budapest, they are: (1) the grand vision of an urban passage-system (the “Inner-City Shopping Centre”6) and the realized architectural elements of this project, these being (2) the Fontana department store (built 1980–1983, demolished 2022) and (3) the Kígyó Passage (or Kígyó Court, built 1977–1978, partly demolished 2019). The contribution is less concerned with the applied architectural formal language of the vanished buildings, emphasizing in their place the (missing) documentation and analysis of the established urban spatiality that, if anything, is even more of an absence.

In our interpretation, the concept of the passage-system was an attempt to revitalize and valorize the city centre while at the same time serving the extant regime’s aspirations and endeavours toward rivalling capitalism. The afterlife of its buildings, their removal and the systemic transformation of the city centre can be read on the one hand as bringing to life the dream-world of the socialist vision of consumerism, an almost naive misinterpretation of capitalism. On the other hand, the transformation could equally be interpreted as real existing capitalism manifesting itself urbanistically, architecturally and culturally: not only are the buildings removed materially, but even their research is hindered by an extreme lack of documentation and neglect of planning documents, placing them on the threshold between myth and reality, existing from now on only in the realm of subjective memory.

Both the Fontana department store building and the Kígyó Passage, along with the wider concept of the Inner-City Shopping District, manifested an Eastern European, socialist fantasy of Western capitalism. Fontana was a department store built by the state, the goods imported by state-owned import-export firms expected to display Eastern and Socialist advancement and progress through their mimetic reproduction and their placement in the city. The Kígyó Passage and the concept of the Inner City Passage System, conversely, was inspired by an essentially nostalgic impulse: the existent typology of passages in Budapest, proliferating from the second half of the 19th century onwards; it attempted to develop a modern system that would create atmospheric passages piercing through the turn-of-the-century perimeter blocks, to accommodate the mixed-use of small scale commercial facilities (shops), restaurants and offices of the service sector such as travel agencies. This vision of Kapsza, Schall and Vedres was an organic development of an existent typology in Budapest, was based on a capitalist built form, and even provided for a better pedestrian network in the Vth district – perhaps even meant to counteract the autogerechte Stadt7 of earlier years resulting in the transformation of inner-city streets to car-friendly highways – yet it nonetheless irrevocably failed as an urban typology in the years when Western capitalism replaced the Eastern vision of it.8

All projects can be regarded as attempts to finally arrive, also architecturally, in the desired West, yet in doing so, they manifest in parallel an architectural paradox and singularity unique to the final decades of socialism. Based on a proto-capitalist typology, this project could only be realized on such a scale in the city centre under socialist property relations, as all real estate and land was in state ownership. To contribute so lavishly to public spaces inside the perimeters was only possible though these paradoxical circumstances. The burgeoning porosity proved to be an irritation to the “smooth projection surface” of new, curated capitalist identities. Porosity and the potential of spontaneous or observant activity is neither welcomed nor desired in late capitalism, whereby the passive capitalist-cosmopolite attitude of the flaneur must give way to the active consumer, who is conditioned for a “detached spectatorism”9 and characterised by a “… turn from belief to aesthetics, from engagement to spectatorship”.10

In this regard, the role of the detached spectator conditioned for consumption, the flaneur is a prototype of the neoliberal individualist consumer. Walter Benjamin already referred to this aspect in his Arcades Project: Indisputably intrigued by them, Benjamin sees passages as “fairy-palaces” [Feenpaläste]11, a “kind of living room” [eine Art Wohnzimmer]12, compares them to grottos, or understands them as the continuation – or even intensification – of the “labyrinthian momentum of the city”13 and principally as “manifestation of ambiguity”, being both street and building.14 These associations with the mythical (labyrinthian) and the sensual and desired (grottoes) are of course neither coincidental nor surprising, as Benjamin, despite all enchantment, does not fail to point out, that passages are primarily places of consumption, specifically of luxury goods,15 and goods [Ware] are in Benjamin’s concept the fetish central to capitalism.

The Typology of Passages and

Bazaars in the Inner City of Budapest

The “passages” to be found in Budapest can be divided into three types. The first (1) is the form of the pass-throughs, known alternately as Durchhäuser16 or átjáróház [pass-through-building], where the pedestrians pass through the courtyards of tenement buildings, where the courtyards are connected but not roofed. In most of the cases, the courtyards originally did not have commercial uses like shops on the ground floor, at most a few workshops. The átjáróház and the courtyards were at the same time the main access to the building’s residences and a shortcut for pedestrians through the large perimeter blocks. Examples of this type are the Trattner-Károlyi Building or the Dobler Building and the Kerepesi-Bazaar, yet even here the Dobler Building definitely had shops and other services on the street level and the naming of the latter (Kerepesi-Bazaar) indicates that the commercial use of the units of street level was already calculated in the plans. The second (2) is the pass-throughs deliberately conceived with a commercial use on the ground floor. The Rösner Court would be an example of this pass-through building (an open courtyard connecting two streets, commercial units designed on the ground floor). Third (3) is the covered shopping street, bazaar or passage, given a type of roofing and integrated into the perimeter block or a certain single building only on the ground floor or ground floor and mezzanine level, yet nonetheless receiving natural light through the glass elements in the ceiling.

The calendar of the newspaper Pesti Hírlap lists eleven “bazaars” in 1911. However, the word “bazaar” by itself does not help in further distinction as it neither reflects the built typology as described above, nor distinguishes between commercial and non-commercial use. For instance, the Unger-building on the Múzeum Ring Road is listed as a bazaar, yet this building, designed by Miklós Ybl himself and built already in 1852, essentially belongs to type (1), as here no commercial use was intended for the ground floor. The courtyard connecting the Múzeum Ring Road and Magyar Street (today), accessible from both streets, was left opened during the day, so that pedestrians could pass through, but was closed during the night. Conversely, one structure not named “bazaar” but deserving a place on this the list is the Röser Courtyard, belonging mostly to type (2) as proposed earlier, as it originally contained small commercial units on the ground floor but was not a passage, as the courtyard was not roofed. Somewhat surprisingly missing from the list is the grand Párisi Courtyard [Udvar], though the predecessor building with an internal passage on the same plot, the Brudern Building, was demolished in 1908 and the new building was completed only 1912–1913.

This building tradition in the Inner City continued in the years of early modernism, as revealed, to cite only two examples, by the building and passage by Gedeon Gerlóczy in Petőfi Sándor Street and the building and (short) passage by Aladár J. Münnich at Vörösmarty Square. After World War II, though, the only addition to the system of passages was the project now under discussion: the Kígyó passage and the one within the Fontana department store.

In 1983, the same year that the Fontana building and its incorporated passage was completed, a review of Budapest’s existing passages appeared in the Hungarian architecture journal Magyar Építőművészet, enumerating these and reporting on their then current state.17 The early modernist building and passage by Gedeon Gerlóczy in Petőfi Sándor Street is not mentioned in this article, nor are some other passages mentioned in the almanack of 1911. Apart from this 1983 article, art historian Márta Nemes published an extensive study on the Haris-bazaar in 1992 entitled “The Old Haris Arcade in Budapest”18 and art historian András Jeney published an online article on the history of the Dobler-bazaar in 202219, which allows the detection of a research gap in the investigation and typification of Budapest’s passages, bazaars and arcades.20

The Inner-City Shopping Centre

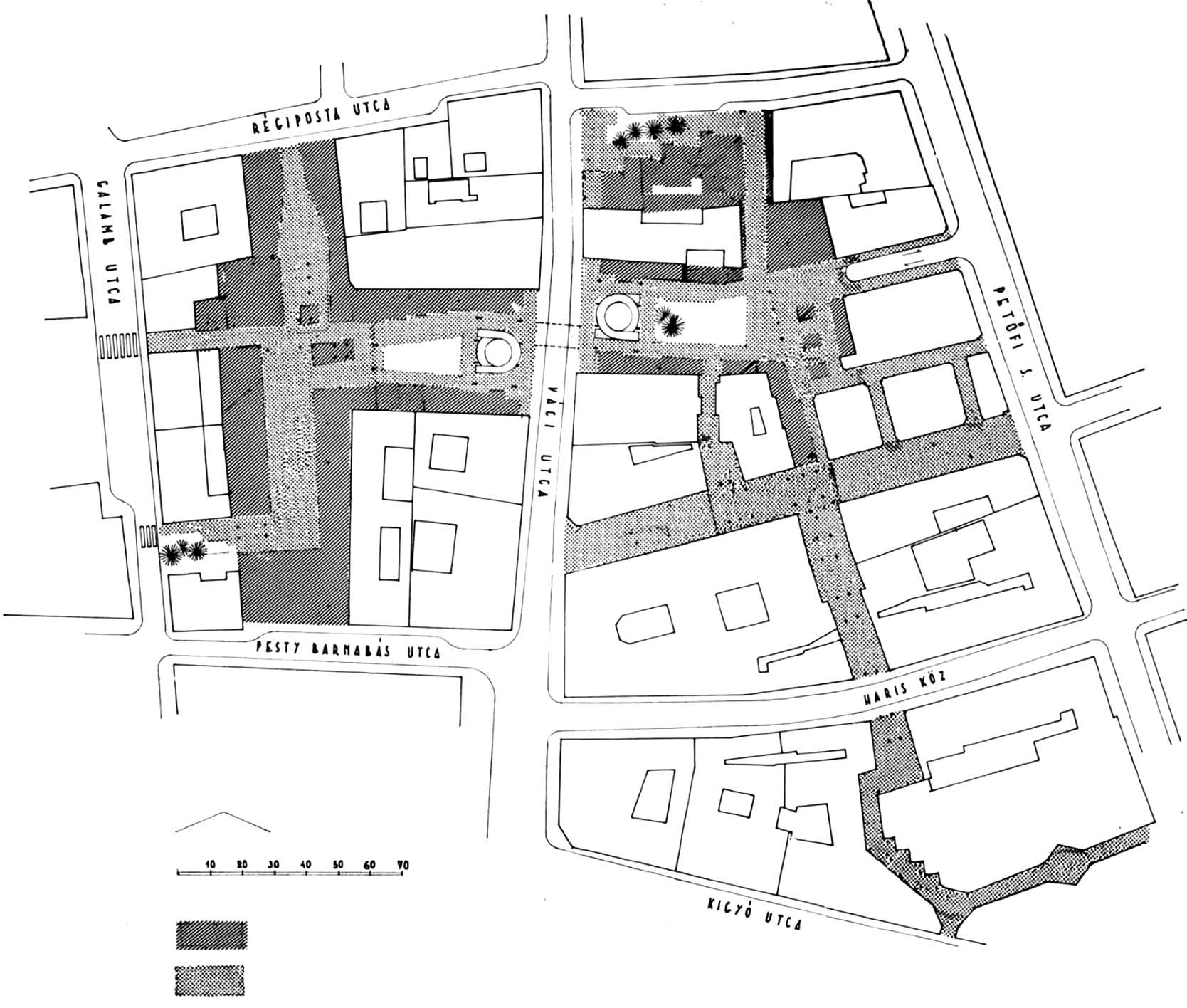

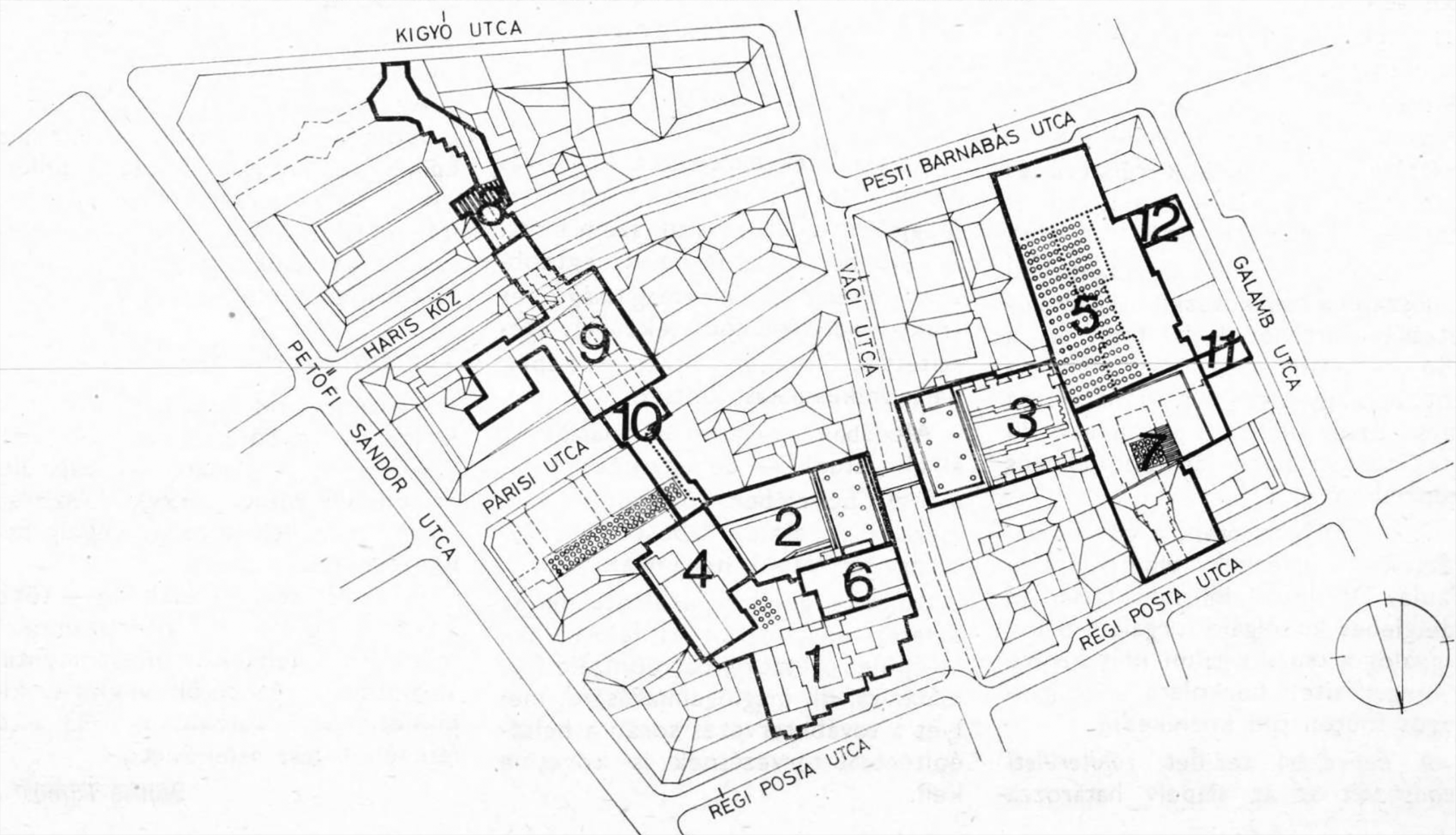

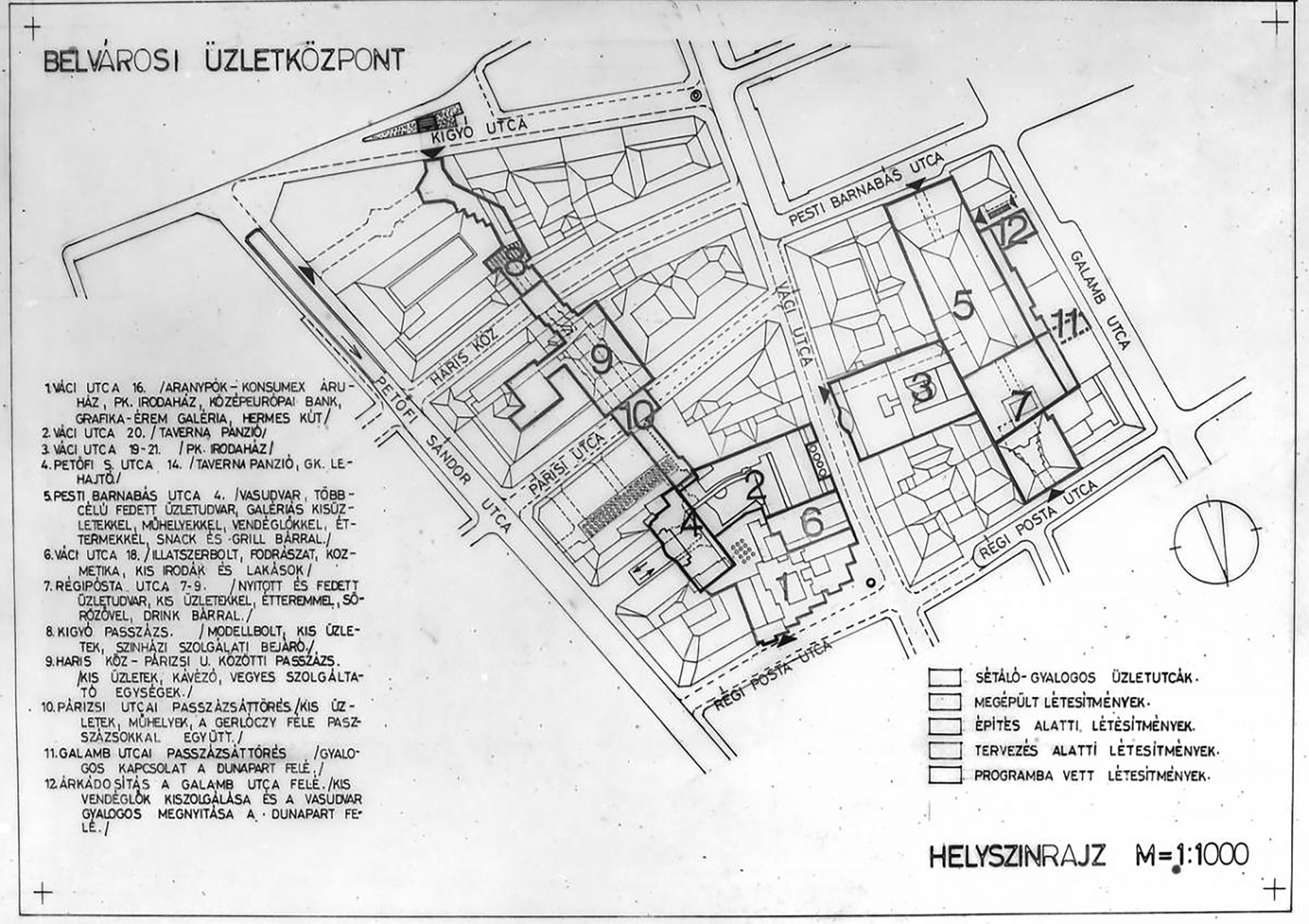

The Inner-City Shopping Centre was a concept developed by the state planning firm BUVÁTI under the leadership of chief architect György Vedres. Inner City Shopping District would probably be a more suitable name for the project, as it was directly addressed the regulation (infrastructural, urbanistic, and architectural) of the “middle part” of Budapest’s Vth district, not (only) the planning of a singular building, a shopping centre, moreover one mainly represented now by the typology of the mall – then (1980s) known in Hungary at most indirectly. The scope of the Inner City Shopping Centre can be divided into three main parts:

- the infrastructural and urbanistic regulation of Ferenciek square,

- the concept for the shopping district bordered by the streets Galamb Street, Régiposta Street, Petőfi Sándor Street and Kígyó Street, and

- the concept of (re)construction, accentuation and recession of the existing buildings on the ground floor level with a system of arcades along the main axis of the Inner City.21

The 1967 Competition

The competition for the Inner-City Shopping Centre was announced in 1967, aiming to establish a tightly interconnected pedestrian traffic system, providing approximately 16,000 sqm of commercial space, and propose new architecture in the many vacant lots22 – hence, interestingly, the term “reconstruction” is often used in connection with the competition and later implementation, as the inner-city still bore the imprint of WWII destruction.23 The call of the competition referenced a segment from the Budapest regulation plan then in force, stressing the qualities of the existing passage inside the Tattner House.24 This regulation plan of the Vth district, passed by the City Council in 1965, divided the district functionally into three parts: the northern third envisaged as mainly institutional, the middle part as touristic and commercially representative, and the southern third as reserved for cultural and academic institutions. The Inner-City Shopping District corresponds, both in location and program, to the middle part of this distribution. The winners of the competition were the architectural partners Miklós Kapsza and József Schall; it is worth noting that the main outlines and characteristics of their winning proposal was implemented in the Detailed Regulation Plan of the Inner-City developed by Vedres and colleagues at BUVÁTI in 1970 and the Inner-City Action Plan completed in 1975.25

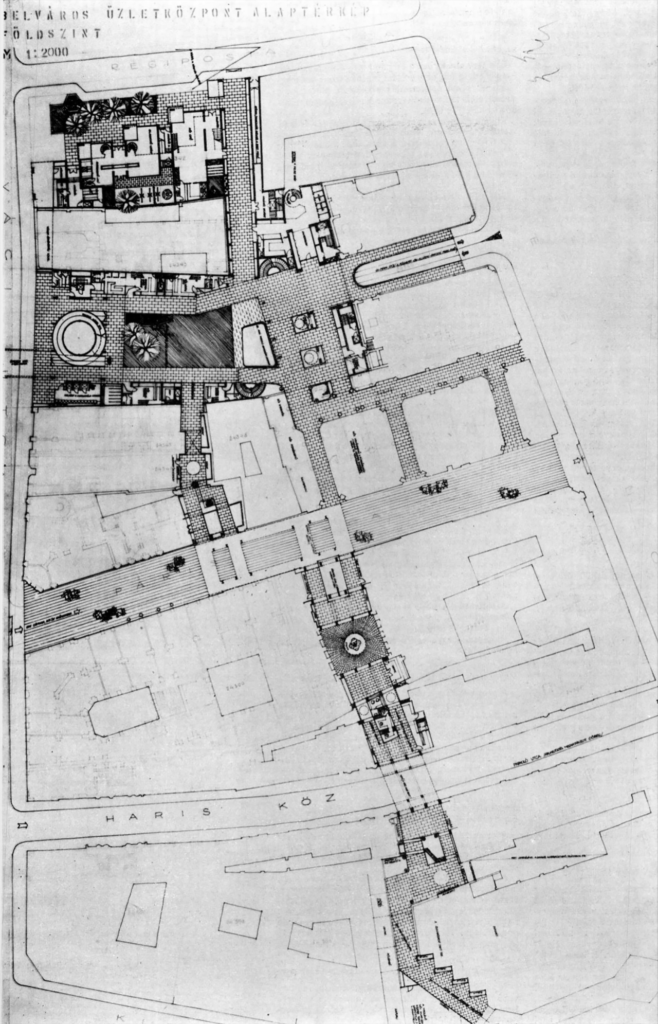

The winning proposal of Kapsza and Schall already outlines a system of passages of approximately 3,800 m2, parallel to Petőfi Sándor Street, starting from Kígyó Street and ending at Régiposta Street, perpendicularly intersecting Haris Street and Párizsi Street It also quite clearly suggests and outlines a new connection of the lavish turn-of-the-century Párisi passage (to be entered at Kígyó or Petőfi Sándor streets) to Haris Street, which later became the Kígyó Passage. Furthermore, the gradual street level setback of the corner building at Régiposta and Váci streets, later occupied by the Fontana department store designed by Vedres, and its own passage connection is also already existent in their proposal. The passage by Gedeon Gerlóczy is integrated into the concept as well, along with a second perforation to Párizsi Street, though not included by Vedres in the later plans. Interestingly, the supply of services and goods for the mixed-use building at the vacant plot of Váci Street 20 is already in this plan solved by managing access from Petőfi street and putting the interchange below ground – almost exactly the solution later used by architect József Finta for the Hotel Taverna (planning: 1982–1985, construction: 1983–1985). The extension of the Párisi Court towards Haris Street displays an almost identical layout to this final built version, which was designed by Kapsza and Schall. The still-vacant plots facing each other along Váci Street (nos. 20 and 19–21) are connected by a pedestrian bridge on the first level, accessed in both cases through a sculptural winding ramp. This layout and arrangement were also absorbed in the later plans, as clearly visible in the plan of the Commercial District and of the Passages in 1982: the drawing already reveals the final form of the Fontana department store, but for the plot at Váci Street 20, the concept of Kapsza and Schall is clearly traceable through the winding ramp and the pedestrian bridge26. Kapsza and Schall hoped to establish their pedestrian network mainly above ground, while the buildings on either side of the street would have accommodated the Adam-Court (on the ground and 1st floor) for men’s fashion and Eva-Court for women. The building on the plot of the Fontana department store was envisioned as a store for children, while the project around the Vas-Court as an “antiques-court” with little workshops and commercial units for handmade and locally manufactured products.27 Additionally the site plan and the frontal elevation plans for the Fontana department store by Vedres from 1981 found at the city archives still show the winding ramp and the pedestrian bridge as envisioned by Kapsza and Schall. It is unclear why the concept of the functions (commercial, mixed-use buildings for hospitality and offices) was changed and when this decision was made. An undated plan, undoubtedly later than 1982, shows the “final” state of the Inner-City Shopping District, yet the passage no. 9 was never implemented.

Capitalism and Streetscape

The peculiar trait of the architects’ proposal is not only its deep understanding and detailed investigation of the urbanistic history of the inner city, but its ability to build on a bourgeois, early-capitalist understanding of the streetscape and intends to continue this tradition. Of course, all the efforts by Vedres to make the Inner City more pedestrian-friendly were counteracted by the technocratic enthusiasm of late modernism resulting in the spatial fragmentation at and around such locations as Ferenciek Square, where the motorised traffic was granted priority only to create tunnels and canyons for cars. It should be clear – although unfortunately no interviews could be made with the architect and all information on his personal stance on the issues can be inferred from the highly edited publications on the projects which he wrote as a leading architect at the firm – that for Vedres, the favoured solution was a multi-layered organisation of traffic, separating motorised and pedestrian traffic. Vedres explains his urbanistic concept as an “inseparable dual purpose”:

“The second major unit of the downtown reconstruction in progress is the Downtown Shopping Centre. Its contemporary layout has an inseparable dual purpose. On the one hand, to address the current urban design and maintenance deficiencies through reconstruction, which are urgent from an urban-planning and aesthetic point of view, and on the other, through taking advantage of the exceptional development opportunity offered by the integration of the vacant plots, creating a shopping centre with a distinctive Budapest character that preserves the valuable features and integrates itself well into the historic or heritage surroundings.”28

He then again stresses the importance of avoiding demolition of intact built substance29 and of creating an organic continuity with the existing building stock.30 Yet against these postmodernist principles, all the Western European cases he mentions as examples to be followed are almost exclusively (late)modernist large-scale tabula rasa projects. The Hötorget project in Stockholm is emphasized not only as exemplary for historic inner-city developments in Europe, but even more its creation of traffic-free pedestrian zones for shopping. Nonetheless Vedres continues by listing Utrecht’s Hoog Catharijne project and Toronto’s Eaton Center as references. Today it is hard to trace what he and the design team might have seen in common between these large-scale ex-novo projects and the proposed reconstruction of Budapest’s inner city. Perhaps Vedres wanted to display his knowledge and awareness of urbanistic trends and models in Western Europe (a ceaseless anxiety of being fallen behind characterising the Hungarian architects throughout State Socialism, as sociologist Virág Molnár also points out31) but it is also likely that he and the BUVÁTI team actually regarded the Inner City Shopping District ensemble as a miniature version of such large-scale developments – not least as they provided ideal models for the vertical separation of traffic. Describing the duality that late-socialist societies experienced when confronted with post-socialist transformation, one article by art historian Géza Boros is very telling. Written in 1991, it sharply denigrates the (architectural) quality of developments of the recent years, finding their greatest fault in how they visibly fall behind Western quality and standards, while at the same time expressing a peculiar resentment towards the burgeoning capitalist cultural intrusion, and its material and architectural manifestations. About the Fontana building, he writes:

“Fontana’s bright pastel interior is reminiscent of Herzmansky’s department store in Vienna, but if you look around you can see that it is in fact a different world: the elevators are industrial and porridge-grey, the ground-floor glass bead fountain is lit by Trabant signal lights, and at night the entrance is secured by a sturdy iron bar (…).”32

While, being deeply concerned by the developments after the fall of the Iron Curtain:

“… the new buildings are stage-set-like and rather mediocre in artistic merit, and despite their attractiveness they are not of very high quality, like the ‘decorative paving’ of the street with the stones used in the West for the kerbing of motorway slip lanes. The street’s lustre has recently been spoilt by ‘working capital’, which is willing to exploit our consumer ‘backwardness’ to the full, and which understandably has no particular regard for what this street could mean for us and would even turn Buda Castle into an American-style fast-food restaurant.”33

The Fontana Department Store

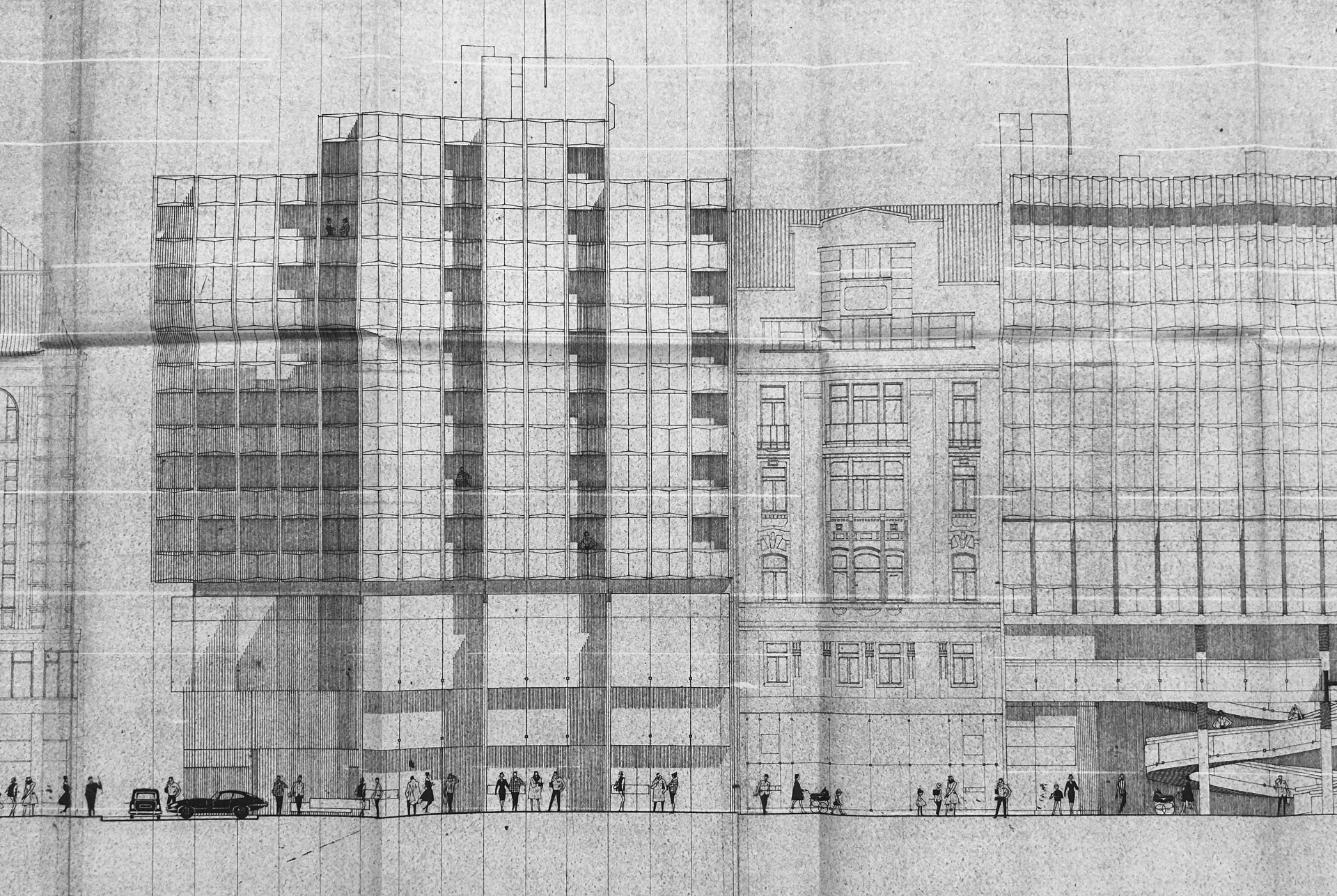

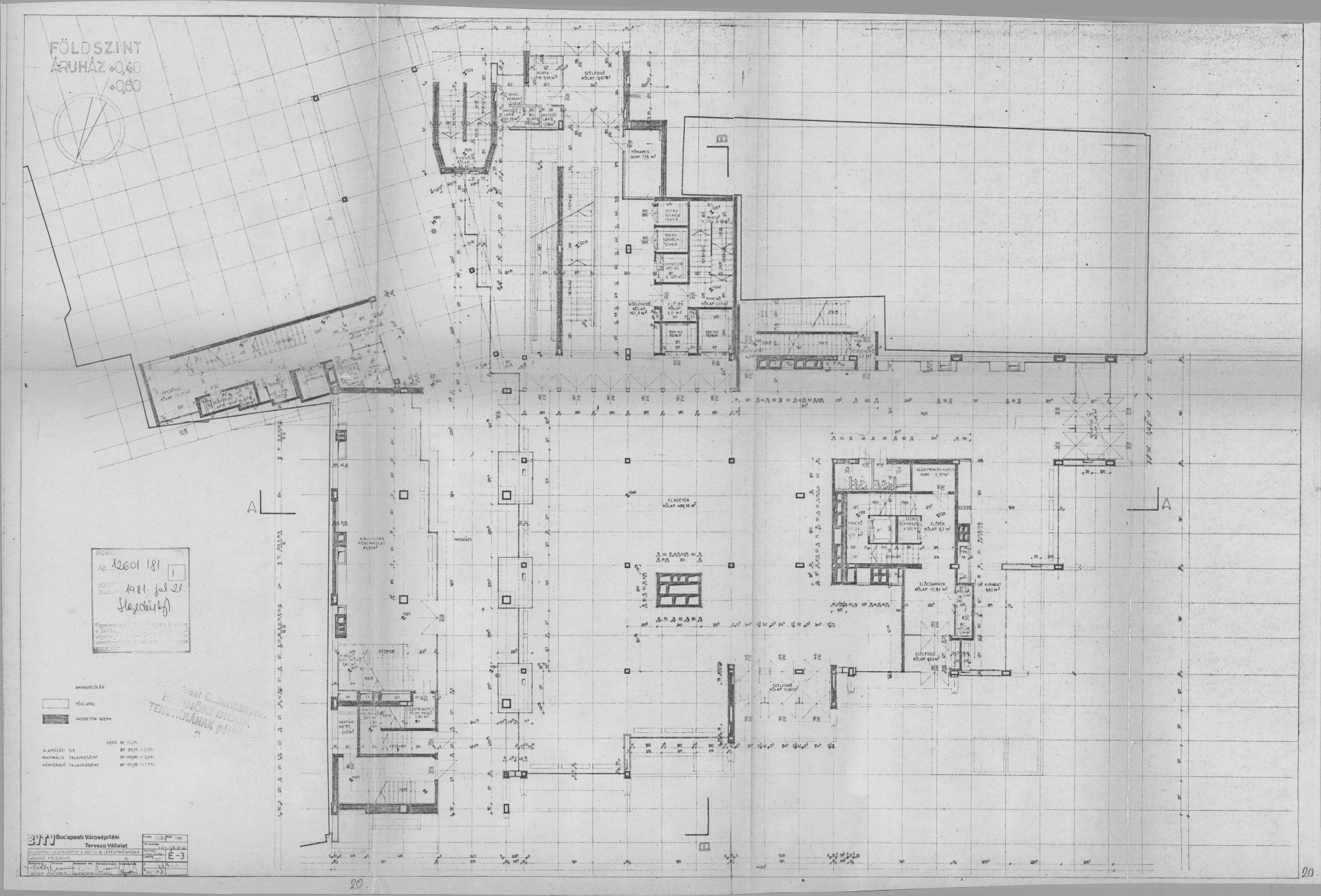

The building originally known as the Aranypók-Konsumex department store was built in the advent of the stagnation years of late socialism in the 1980, between 1980 and 1983. As the clients, the state enterprise Aranypók [Golden Spider] was a supplier of fashion goods (such as underwear, fine knits, homeware, beachwear and imported items from other brands) and Konsumex was the state-owned import-export firm controlling and managing what products arrived from abroad. The chief architect was György Vedres and it can be assumed that he consulted Kapsza and Schall on the design, at least in terms of the design’s accordance with the BÜK proposal of 1967. Receiving the name of Fontana in 1985 after a public competition for the new name, it opened in July 1983, while construction work started in 1980 and planning in approximately 1977. However, the winning proposal in the 1967 competition for the masterplan of the Inner-City Shopping Centre by Kapsza and Schall already anticipated the final footprint of the buildings: the volume is gradually set back along Régiposta Street from Petőfi Sándor Street towards Váci Street, with a generous passage on the ground floor for pedestrians connecting Régiposta Street through the depths of the perimeter block with Párisi Street integrating the early-modern passage by Gedeon Gerlóczy into the network.34 From the outline of the sidewalk and the cars parking in front of the building in the frontal elevation drawing we know that in the beginning of the 1980s these now-pedestrian streets were still open to motorized traffic, thus Kapsza and Schall proposed a little piazza in front of the building at the corner of Váci and Régiposta Streets. Given the rather long time delay between the urbanistic proposal and the project realization, the faithful adherence to the guidelines is rather remarkable.

The Aranypók-Konsumex project was designed as a mixed-use building: commercial functions on the ground floor, the mezzanine (1st floor) and the 2nd floor (the department store); a rooftop terrace on the 3rd floor; then three residential towers starting from this level, each consisting of 7 floors (plus an attic floor for technical equipment). The volume was animated and formed on two levels: the basis (ground floor plus 2 upper floors) was gradually set back from the plot boundary towards the corner (Váci Street and Régiposta Street) and also stepped vertically – making the 3rd floor the one with the largest sales area – while breaking the upper volume into three towers allowed for more light and air inside the ensemble. The store has a large entry space from Váci Street as well as from Régiposta Street Entry for the staff and access to the residential towers was provided from Régiposta Street, almost at the “corner” of the buildings and through two other cores, accessible from the inside of the perimeter block, which could be reached be a newly opened passage from Régiposta Street. The passage was 6.7 m high, spanned over two floors vertically, and ca. 3.6 m wide, with glass facades along both sides, shop windows towards the department store with integrated glass display-boxes and a shop window to the other side as well. The passage was kept illuminated during the night. Uninterrupted circulation was granted of the sales floors, though the escalator was placed in the back part of the building and the store. A wall covered in green marble (most possibly identical to the material used in the Kígyó Passage) separated the escalator from the stairs, which had to be used for descending, as the escalator only operated upward. The plinth, i.e., the first three floors, had large glass facades towards the two streets, with the logo of the department store on the corner of the building.

The residential towers had to be redesigned as office space literally at the last minute: in the furnishing plans for the building, the cores are still indicated as “entry to the apartments”, though in the same planes the floors in the towers are already furnished as offices. The motivation behind the decision to change the function is difficult to retrace, as the Regulation Plan strictly designated the middle part of the inner-city for trade and tourism with housing on the upper floors of the newly established buildings and not for offices.35 However, apparently the demand for office space in the inner city forced the designers to altered the program and changed design.36 In hindsight, this decision can appear almost ironic, since during the post-socialist transition, entire office-corridors arose in Budapest, placing office buildings in the outer districts, while investors and real estate developers are building (luxury) apartments on the very sites of former late-modernist buildings with public, administrative or office functions in the inner-city. And the successor building on the site of the Fontana department store is no exception. The developer, who acquired the plot already in 1993 in a process labelled as “turbulent” by the Hungarian economics newspaper Világgazdaság37, replaced Vedres’ building with one where the retail function occupies the first two floors and luxury apartments on the upper floors.

The layout of the towers established a sense of interiority, as three of the facades were facing each other (looking to the north, east and west), while thanks to the recurring set-backs, even some of the offices from the towers in the second row could have a view towards the Váci or Régiposta streets The towers featured a distinct facade of prefabricated metal elements, originally planned with slight alterations in the rhythm (though not implemented in construction), while the window glass was covered by a sun-protection film in a slightly reflecting brownish-brass colour – a feature now strongly associated with the 1980s. The architect and team designed also a layout for the public terrace with possibly a café or restaurant, including the design for such specific Items as plant containers, though the terrace never opened.

Essentially, the department store displays a singularity within late-modernist architecture, making it specifically “socialist” or East-European precisely in its attempt, in fact somewhat successful, to be up-to-date and Western. And yet, exactly these traits made the buildings ambiguous in character, with its imitative status hindered integration into Real Existing Capitalism. The department store was the final major effort within the stagnation years of late-state-socialism, possibly financed by credits from the West, to prove to Hungarian citizens that they were not lacking anything in the Eastern-bloc: neither good architectural design, nor the material means of the products that was available in the West. Ironically, these aspirations were never achieved, as neither the building materials nor the constructional skills, nor consumer products of (high) Western quality, were available. However, the department store succeeded in demonstrating a unique quality, yet one possibly even overlooked by the planners and city-users of the time: the availability of land, as the (building) plot was not subject to property speculation in Socialism, and all land and construction sites were owned by the state. The result was the lavish contribution of public space around the Fontana department store, and by extension the generous passage-system of the Inner-City Shopping District. And precisely this unique result faced the harshest change during post-1990 privatisation as all efforts to maintain the passage system fell apart.

Vedres aimed for an (architectural) design in no way inferior to a department store in the West, hence his proclaimed and advertised models were projects in Sweden and Holland. In the applied architectural formal language, this ambition succeeded, but not in the availability of similar materials and construction techniques, where the cheaper replacements made the building age before its time. Reactions to the completed building in the contemporary press illustrates this discrepancy or ambiguity. On one hand, the new department store and the BÜK project were celebrated as a “thoughtful development”, a “cosmopolitan centre”38, an “advanced city” and a “remarkable city centre”39, a “true cosmopolitan department store”40 but others pointed out the long planning period and the construction time of 6 years, or the lack of quality in the products displayed and sold, as well as the available applied materials and technical solutions of the building as manifestations of the persistent irreconcilable inferiority to the West.

This discrepancy places the Fontana department store on the threshold between “socialist” and “capitalist” late modernism. Planned to compete with the West, to exercise Western consumer capitalism and consumer behaviours, it could only fail in this aim, as the coulisse what not yet convincing. It resulted in a mere mock-up. The qualities of the department store were expected from the displayed goods and from Its up-to-date architectural design and technical solutions (such as an escalator or lifts from a Western manufacturer, in the beginning of the planning process strictly forbidden) and the function (department store) itself. However, the real qualities of the project lay within the traits enabled only by the “Socialist condition”: the generous contribution and design of public spaces, providing public and pedestrian access to semi-public space within the perimeter bloc and a rooftop terrace, or even the custom-made design furniture of the department store, which (again) stemmed from the “Socialist condition” of the unavailability of Western products and the concurrent of time for planners and workers to manufacture “atypical” items. And these two particularities or singularities are also exactly the traits unrecoverably lost within the post-socialist transition: the architecture (the building is demolished), the spatialities (the passage system is closed) and the custom-made interior design and furniture (lost).

Real Existing Capitalism swept away all late-modernist socialist architectures in the Inner-City, not only for their architectural formal language – often labelled strange, disconcerting or even embarrassing as reminders of the “overcome past” – but primarily because of their lavish treatment of public space, allowing for public space on ground floor level, on a – now – privatized plot. As such, the replacement for the Fontana department store exploits its site to the maximum, significantly narrowing the streets Váci and Régiposta, eliminating the little piazza at the corner, making the replacement of the fountain quite impossible and closing the passage once open to the public.

The Kígyó Court

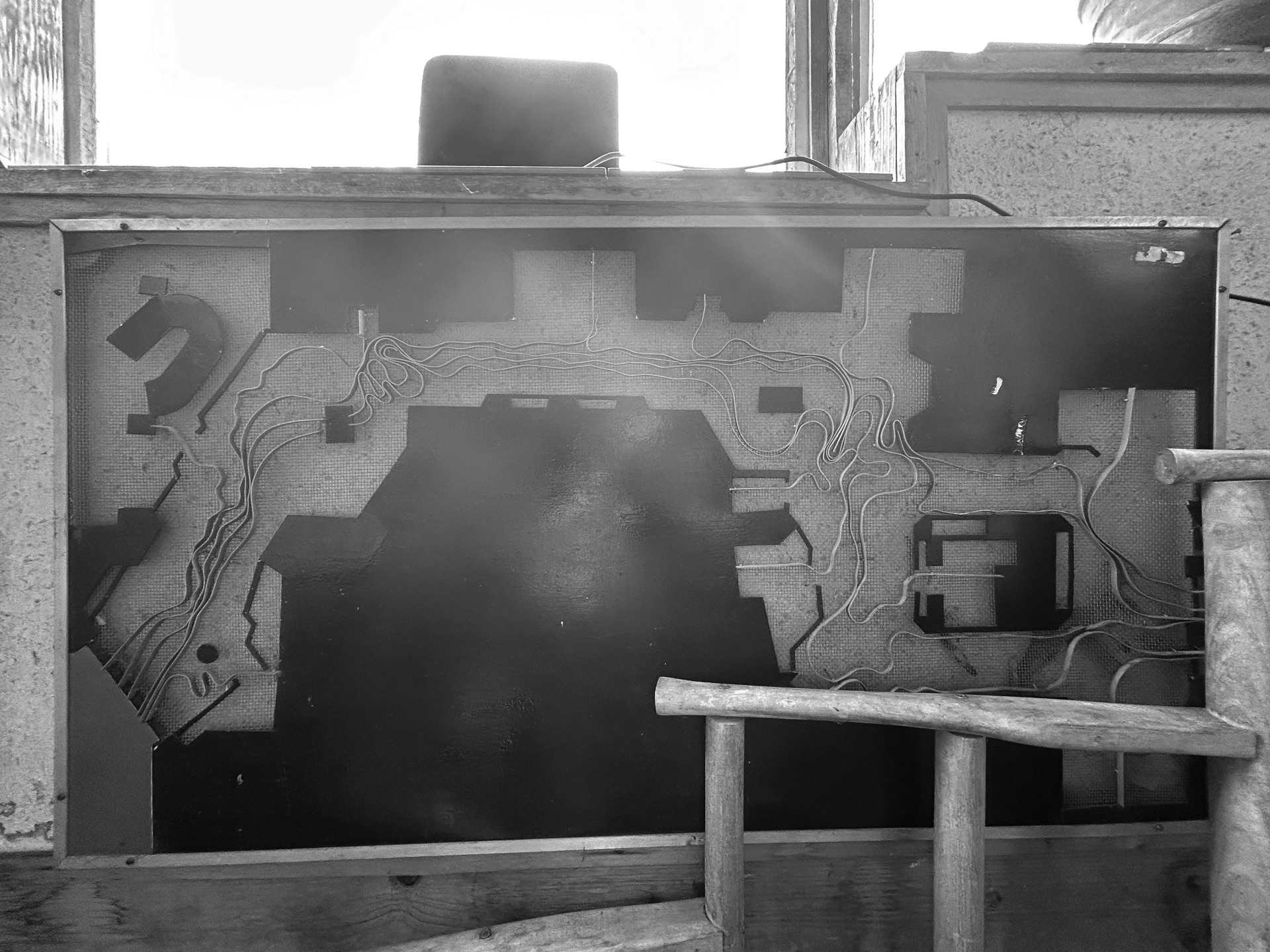

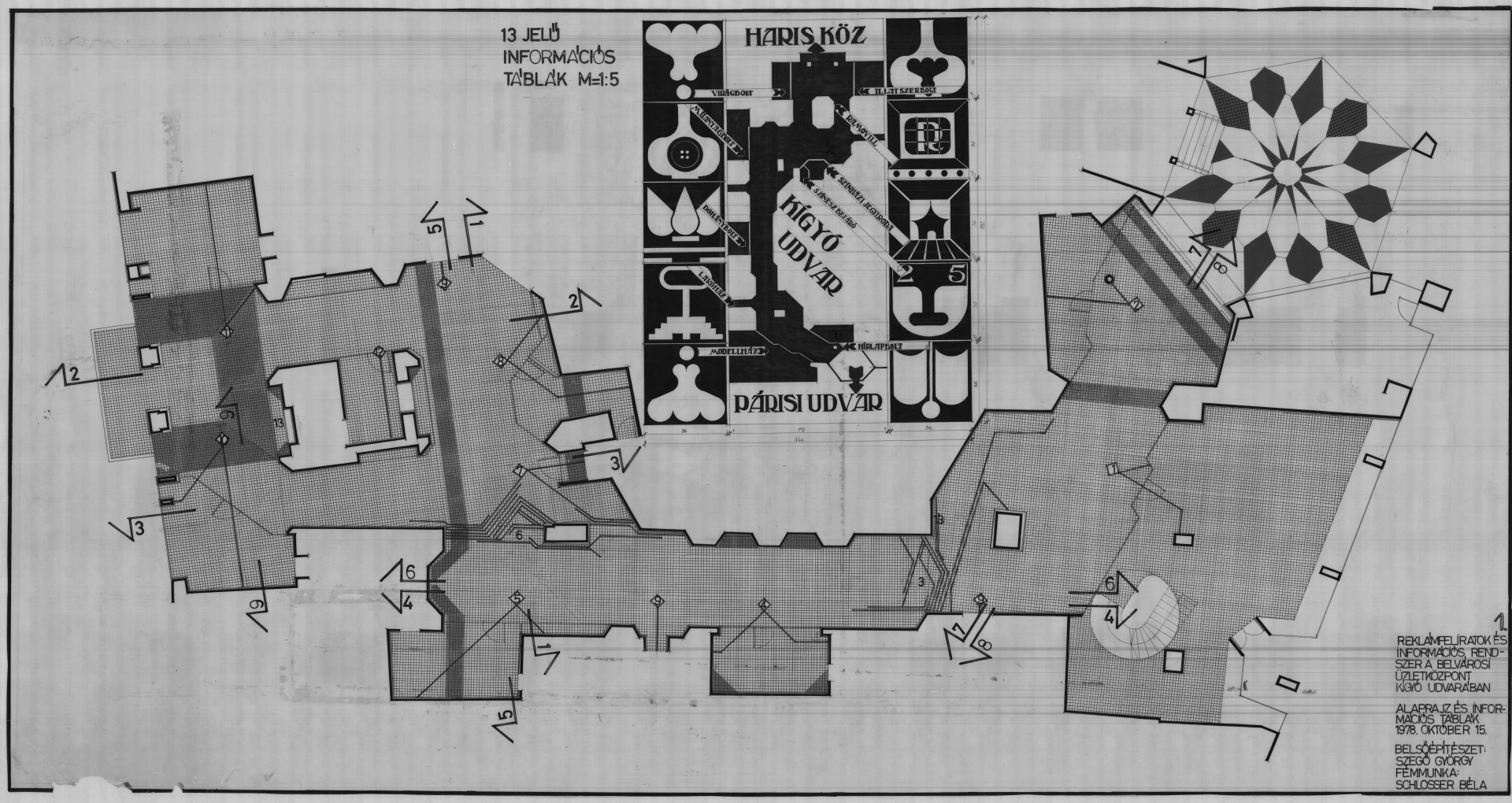

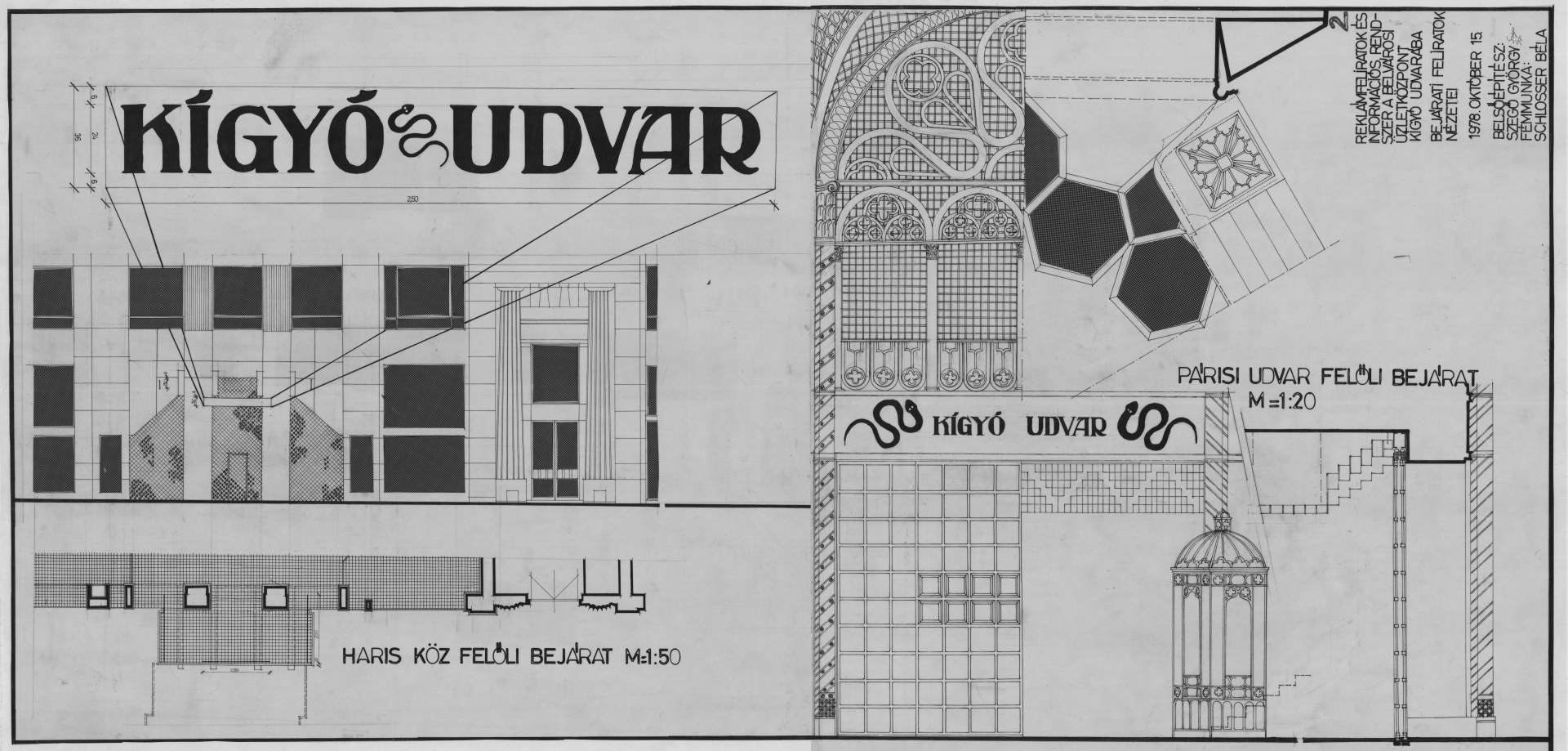

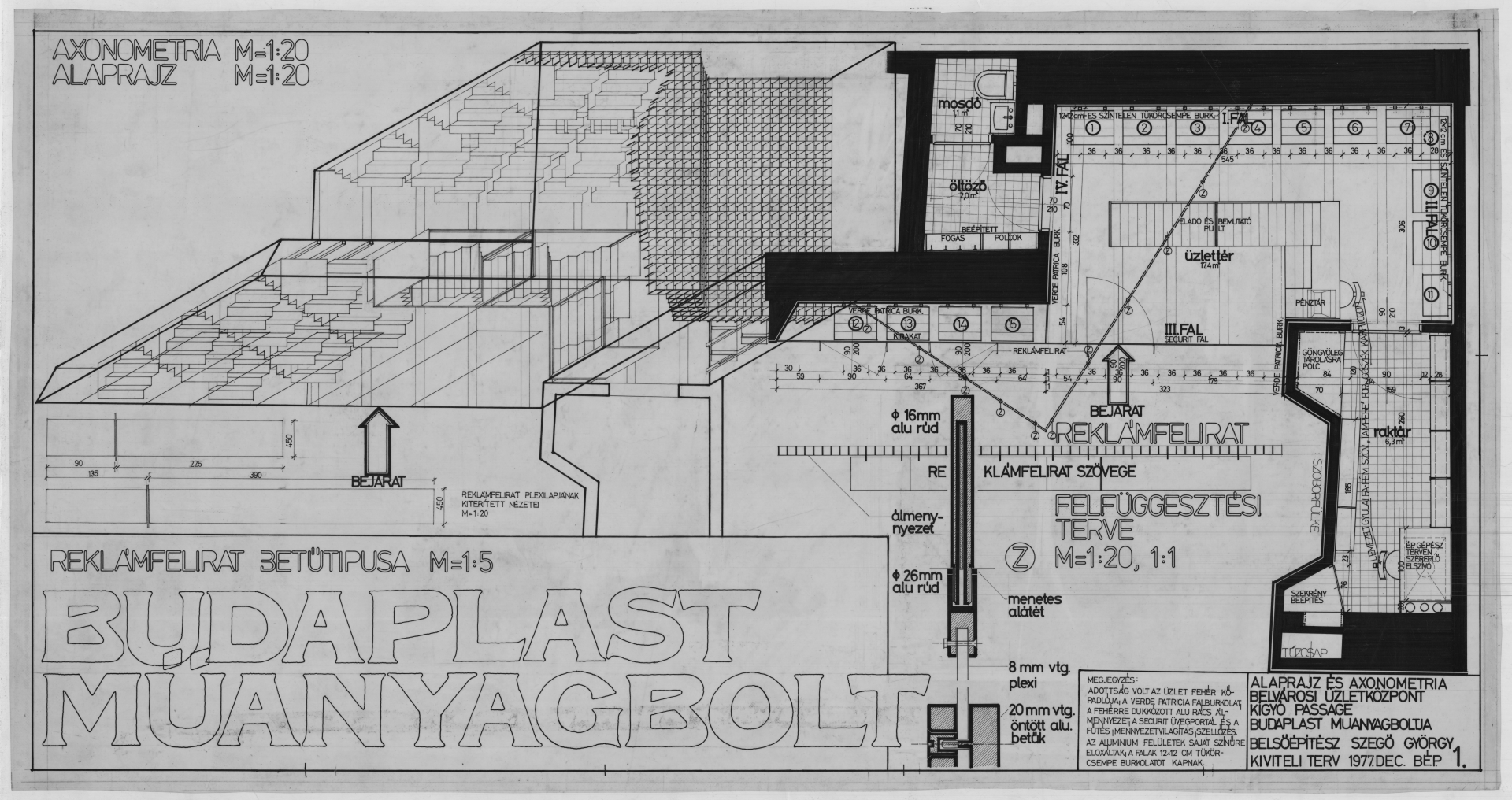

The Kígyó Court project posed a challenge for scholarly analysis, as currently there are no available plans or even photographs depicting the planned and originally executed state of this project. This lack of documentation lies within the overall status of late modernist architecture during and in the first years of post-socialist transformation. When the state planning offices were dissolved after the regime change, there was no governmental or professional regulation to guarantee the administration, collection, archiving and storage of the documents, models and materials produced in the state planning firms. Hence, due to the lack of framework an immense amount of plan material (including sketches, models, documentation) physically vanished. After all enquiries proved unsuccesssful in the local archives, where the plans or documentation of the state planning firm or the architects working there might have been found, and no unfortunately no interviews with the architects listed as chief planners could be conducted any more,41 architectural-historical research on the Kígyó Passage had to be put on hold as possibly unfit for academic investigation due to the lack of documentation. The passage itself is still existent, though extremely dilapidated through years of neglect, significantly transformed through the recent reconstruction of the connected Párisi Passage, and closed off from the public. Only by chance, the author stumbled upon a reference made on the Kígyó Court project by one of the interior designers, György Szegő, who kindly made himself available for an interview and presented previously unpublished drawings and models on the project from his personal archive to the author. As a consequence, all the following information on the Kígyó Court project draws upon the personal testimony of architect and interior- and stage designer György Szegő provided in a personal interview on 22 March 2024.

The Kígyó Court was planned between 1973 and 1979 as an interior design project. Its small team had a peculiar construction, since it was then impossible for architects to work independently and open up a private office and firm, only instead to practise within one of the state planning firms. However, apparently, architects holding the position of associate professor and employed by a university could take part in competitions under their own names, as independent architects, while a kind of grey zone existed for commissions inside the framework termed the “Off-Budget” [Költségvetésen Kívüli – KK] project. The architects József Schall and Miklós Kapsza, both associate professors at the Technical University of Budapest, regularly assumed “Off-Budget” commissions at the Department for Residential Building Design. One of these was the commission for the complete interior design of the passage, assigned to a team of two young designers: György Szegő, then a young architect and student at the University of Applied Arts, and metal designer Béla Schlosser.

In my interview with him, Szegő explained – as I only realised later – the outline of the Kígyó Court using a metal model of streamlines. The initial idea was to design the suspended ceiling of the passage as fluid forms, which would have corresponded with the rest of the interior design of the shops. At this point, I had to ask about this second peculiarity, which I could never fully understand: why shops? Why a passage? As Szegő explained, at the end of the 1970s, there was a huge demand for small-scale retail units in the inner city. It was this demand, combined with a desire to return to the fin-de-siecle and modernist ambitions to establish a passage system in the Inner City of Budapest, that led to the realisation of the project.

The Kígyó Court was to connect the opulently eclectic space of the earlier Párisi Court with the small side-street Haris Street. As a result, from the busy intersection of Ferenciek Square (then still Liberation Square), one would pass through the Párisi Court and enter the Kígyó Passage as an extension, a second arm, with the Párisi Court leading to Petőfi Sándor Street and the new Kígyó Court to Haris Street, establishing a much-needed connection though the deep perimeter block. The immediate connection of the new Kígyó Passage to the old Párisi Court thus became a point of significant architectural interest, indeed an unmediated encounter between the formal language of late-modernism with and historicism. From these two equally enclosed spaces, the view into the respective “other” passage was like looking into another world; two worlds that clashed “stylistically” in their formal language yet were physically and structurall seamlessly connected. Szegő confirms the principle explained by architect Csaba Virág in an interview concerning the design of his National Power Distributor Station in the Castle District of Budapest: to design in anything but a contemporary architectural language was never considered as an option by the time. As such, the interior of the Kígyó Passage had to be contemporary as well.

Szegő explained that the fluid lines of the suspended ceiling would have resonated with Vedres’ design for the pattern of the decorative paving of Ferenciek Square, which itself depicted abstract lines leading to street crossings and buildings entrances42. Why it remained only a model lies in the often-cited realm the Socialist shortage economy: the limited availability and poor quality of the metal, along with limited construction skills and possibilities. Hence, the designers were forced to shift to a honeycomb structure of prefabricated modules originally intended to cover facades, produced and installed by the Hungarian firm Fémmunkás43. The young designers regarded this limitation as unfortunate, although Szegő eagerly admits that some of the designers and construction workers of Fémmunkás were highly skilled and helped them in realising their complex geometry. Nonetheless, the prefabricated elements could not be modified, one result of which is the exposure of the mounting where two or more panels are joined, as the honeycombs partly overlap, revealing the irregularity of the perforation.

Continuing through Szegő’s personal archive, we find a cardboard model of a mirrored shop-interior with a custom-made shelving system, which turns out to be a maquette for the showroom of the plastics manufacturer “Budaplast”, or hand-drawn sketches of the passage as well as construction blueprints, revealing that the characteristic green stone-cladding of the passage is genuine marble from Bulgaria. Other documents include hand-drawn orthogonal projections of the floorplan of the passage, which show the placement of artistic works such as a statue, and a great drawings on the concepts of the signage system: the graphic design of the sign, the fonts, as well as the materials used for the signage.

The realisation that all this effort put into the project is already partly lost, and the built outcome significantly neglected and closed off, making not only the spaces but also late modernist design unavailable, and overall not regarded as architectural and material heritage worth saving is Indeed a bitter pill. Indeed, the honeycomb-structured false ceiling of the Kígyó Court might be one of the last structures of this type still intact and in its original location, even though this design or type of false ceiling was very popular in late-modernist building and should constitute as a material witness of their time.

The Result of Neoliberalist Transformation: the Smoothing Out of Porosity

In conclusion, the history of the passages of Budapest’s Vth district can be regarded as mirroring the political and socio-cultural changes in Hungary in many nuances, as they portray a transformation from spaces of controlled spectacle and consumption to ambiguous and liminal spaces (after 1990) with the potential to become counter-spaces, to be finally smoothed out through the privatisation of public space, the limitation of access and the surveillance and control of the (former) public spaces. With the help of the concepts of porosity (as defined by Sophie Wolfrum and Alban Janson in their book The City as Architecture) the real extent of the urbanistic deficit caused by this post-socialist transformation becomes evident. As such, the passage system of Budapest’s inner-city district can be seen as a concept guaranteeing porosity and establishing threshold spaces: characteristics and factors construed as by all means positive by Wolfrum and Alban, who, agreeing with Stavros Stavrides, see the porous city as an alternative model to the modern city:

“Arcades and porticoes … and courtyards are interim spaces within building volumes that can be read in various ways, as spatial intersections that are not terminated sharply by an exterior wall but only partially surrounded, built over, or partly closed off, semi-public, semi-private, half inside, half outside. They break down the strict division by which the exterior space is located outside the building volumes and the interior space within them.”44

This resonates of course with Walter Benjamin, who understood the passage as the classical form of interior for the flaneur45. Hence passages are exemplify the threshold space or ambiguous space, as they are semi-public and semi-private, partly interior, partly exterior, but also because of their atmospheric attributes, of which the lighting conditions play a general role, as daytime and night-time blur and transgression is manifested not only spatially (using it as a shortcut as “compact architectural masses become perforated”46) but phenomenologically.

The Fontana department store, and even more so the Inner-City Shopping Centre as an urbanistic concept of pedestrian passages through late 19th–early 20th century perimeter blocks, emerge as specific sites and manifestations of a particular kind of late-socialist fantasy of consumer capitalism. This analysis proposes to view them as attempts to achieve the West, since the concept of the interconnected passages through the perimeter blocks in this part of the inner city already emerged at the turn-of-the -century. This converse demand was addressed by the designers by proposing a typology that was quite specific to Budapest: the system of small-scale passages which evokes the city’s traditions and, on the other hand, offers compensational space for the pedestrians, superseded from several parts of the street within the framework of the very same modernist program.

The defining paradox and peculiar feature the political context is that an urbanistic scheme of this scope could only arise during state socialism, where the framework of public property enabled such a large-scale urbanistic and architectural intervention. A consumer-oriented typology realizable only with state property ownership – or conversely, a socialism that enabled the physical manifestation of the consumer-capitalist imagination, in turn partly nourished by nostalgic concepts about the turn-of-the-century, pre-war era and partly entirely phantasmagorical visions of capitalism from the Eastern perspective. When, however, real existing capitalism entered Eastern Europe in the 1990s, this concept and typology proved unfitting within the actual framework of neo-liberalist, capitalist consumption, or as Walter Benjamin defines transitions: “Every epoch, in fact, not only dreams the one to follow but, in dreaming, precipitates its awakening. It bears its end within itself and unfolds it – as Hegel already noticed – by cunning.”47

The Inner City Shopping Centre and the Fontana department store were suitable environments to “practice” or to “act out” capitalism during the final years of late socialism, however they became superfluous amidst framework of neoliberalist post-socialist transformation: first they became counter-spaces as empty monuments, between architecture and ruin and then they were privatised, closed off or removed entirely. British architecture theoretician Douglas Spencer describes the scenography of contemporary architecture as a friction-free, smooth space48; what makes architectures smooth is not a literal, a formal architectural feature, but their compliance with the will of the neoliberal investor. In Spencer’s concept smooth is the epitome of late capitalism, as: “If pliancy is the logic, smoothing is its tactics … Everything is to be processed, blended, in an operation in which difference is valued on condition that it goes with the flow, that it renounces all antagonism. Nothing must be repressed but everything must comply. The very possibility of contradiction is smoothed out of existence.”49

Mark Fisher understands capitalist realism hereby exactly as to be “seamless”50 and philosopher Byung-Chul Han notes “smoothing”51 as the very practice of stripping anything from negativity and hence complexity. The discussed post-socialist transformation can in conclusion be regarded as the spatial manifestation of a phenomenal smoothing out of differences.

This paper was supported by the Open

Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

Gyöngyvér R. Győrffy, PhD. candidate

orcid: 0000-0002-7913-9376

Department of Architecture Theory

Technische Universität Berlin

Straße des 17. Juni 135

10623 Berlin

Germany

gyoerffy@tu-berlin.de

1 BOROS, Géza. 1990. Áruházi séták VII. Luxus, Fontana. Kritika, 20(11), p. 32.

2 The acronym BUVÁTI stands for Budapest Urban Desing Company [Budapesti Városépítési Tervező Iroda], a state planning office that existed from 1952 until the regime change in 1989/1990.

3 FISHER, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zer0 books.

4 Orig.: „… offensichtliche Demonstration kapitalistischer Potenz …”: BRODOWSKI, Nina. 2005. Geschichts(ab)riss. In: Misselwitz, P. et al. Fun Palace 200X – Der Berliner Schlossplatz. Abriss, Neubau oder grüne Wiese? Berlin: Martin Schmitz Verlag, p. 58.

5 Fisher, M., 2009, p. 2.

6 [Belvárosi Üzletközpont – BÜK]

7 Hans Bernhard Reichow introduced his concept of “the car-friendly city” in his 1959 book under the same title: REICHOW, Hans Bernhard. 1959. Die autogerechte Stadt. Ravensburg: Otto Maier.

8 The flight of commercial tenants out of the inner city and the formerly main shopping streets of the districts only intensified radically after the proliferation of the mall typology, often inserted quite insensitively into the existing urban fabric of Budapest. This genre was originally termed pláza [plaza] in Hungary, as the first mall erected in 1996, Duna Pláza, arose in a then-dilapidated, post-industrial area of Pest. While the first plazas were built in the outer districts of the city, the typology rapidly entered the inner city and the historical districts. The often-declared intention and promise of politics to limit the establishment of new malls within the city could never permeate the logics of capital and convince economical stakeholders. All culminated in the erection of the mall Etele Pláza in 2021, despite a governmental ban on the building of new large-scale malls effective from 2012 (modified in 2014 and 2015). For a detailed typology of malls in Budapest see: SIKOS, T. Tamás and HOFFMANN, Istvánné. 2004. Typology of shopping centres in Budapest. Földrajzi Értesítő, 53(1–2), pp. 111–127.

9 Fisher, M., 2009, p. 6.

10 Fisher, M., 2009, p. 5

11 BENJAMIN, Walter. 2020. Passagen, Übergänge, Durchgänge: eine Auswahl. Ditzingen: Reclam, p. 11.

12 Benjamin, W., 2023, p. 68.

13 Benjamin, W., 2023, p. 16.

14 Benjamin, W., 2023, p. 46.

15 “Passages are the centre of the trade of luxury goods” and “… passages, a new invention of industrial luxury …”, Benjamin, W., 2023, pp. 10–1, 67.

16 “Als Passagen sind sie ein Grenzfall. In ihnen wirkt die Tradition der Durchhäuser nach.” Geist generalising on the passages of Budapest in GEIST, Johann F. 1979. Passagen. Ein Bautyp des 19. Jahrhunderts. München: Prestel, p. 169.

17 PAPP, Katalin. 1983. Régi passzázsok Budapesten. Történetük és mai állapotuk. Magyar Építőművészet, 32(3),

pp. 28–30.

18 NEMES, Márta. 1992. A régi Haris-bazár. Művészettörténeti Értesítő, 41(1–4), pp. 114–132.

19 JENEY, András. 2022.

Az egykori Dobler-bazár. Egy elfeledett átjáróház a Király és Paulay Ede utcák között”. Építészfórum [online]. Available at: https://epiteszforum.hu/az-egykori-dobler-bazar–egy-elfeledett-atjarohaz-a-kiraly-es-paulay-ede-utcak-kozott (Accessed: 22 January 2024).

20 In terms of typology, both Papp and Nemes refer to J. F. Geist’s fundamental work from the end of the 1960s.

21 HEIM, Ernő. 1968. A “Belvárosi Üzletközpont” tervpályázata, 1967. Magyar Építőművészet, 17(2), pp. 4–7.

22 Heim, E., 1968, pp. 4–7.

23 “The area in discussion still bears the scars of the war …” N.N. 1970. Városrendezés: Híd a Váci utca fölött. Új Magyarország, 45(7), pp. 22–23; and “… as a still today lingering remnant of war destruction.” BEÉ, Zsolt. 1969. A belvárosi üzletközpont gazdaságossága. Városépítés, 5(1), pp. 13–15.

24 Heim, E., 1968, pp. 4–7.

25 VEDRES, György. 1979. Belváros gyalogos utcák, Belváros Felszabadulás téri együttes. Magyar Építőművészet, 28(6), pp. 9–11.

26 These two sites were in the end not designed by BUVÁTI and Vedres but as well by architect József Finta (1935–2024, LAKÓTERV), best known for his hotel designs.

27 Beé, Zs., 1969, pp. 13–15.

28 VEDRES, Gy. 1982. Budapest Belvárosának rekonstrukciója. Magyar Építőipar, 31(5), p. 283.

29 “The architectural solution associated with the development of the downtown area avoids the demolition of valuable buildings as far as possible and adapts to the existing building and streetscape conditions.” Vedres, Gy., 1982, p. 284.

30 “In this way, the principle prevails that the transformed city centre should not change decisively in its ‘character’, scale or atmosphere, but at the same time, it should be a coherent whole, blended with the old elements, creating an organic continuity of the character of the city that has evolved.” Vedres, Gy., 1982, p. 284.

31 “Architectural modernism was thus understood as a linkage to Western European professional discourse and offered a tool for reimagining Socialism as an alternative modernizationist project …” MOLNÁR, Virág. 2013. Building the State. Architecture, Politics, and State Formation in Post-War Central Europe. New York: Routledge, p. 114.

32 Boros, G., 1990, p. 32.

33 Boros, G., 1990, p. 32.

34 It should be noted that the decision for a gradual setback of the volume towards the corner was not obvious, as most of the competitors (at least those whose submissions are available for research) did not propose a setback, with the exception of the proposal by Tamás Böjthe/Sára Cs. Juhász/Endre Rácz, who envisioned a large-scale opening of the corner and the ground floor, but in connection with the corner building and the building at Váci Street 20 designed as a single megastructure.

35 The winning proposal by Kapsza and Schall already designated all upper floors for housing in the newly built edifices (AT. 1970. Világító járda a passzázssoron. Esti Hírlap, 15(87), p. 119; Heim, E., 1968, p. 4.) as for the aim was to build ca. 150 new flats within the scope: N.N., 1970, p. 22. Also: “Establishing offices is not desirable in this area.” Beé, Zs., 1969, p. 14.

36 VEDRES, Gy. 1984. Belvárosi Üzletközpont V., Váci utca 16. Magyar Építőipar, 33(1–2), pp. 278–284.

37 MAGOS, Katalin. 1993. Bérbe adta a német vevő. Világgazdaság, 25(211); “turbulent” [Hungarian: viharos].

38 HALÁSZ, J. 1979. Áruházak, üzletsorok. Est Hírlap, 24(77).

39 N.N., 1970, pp. 22–23.

40 EGERSZEGI, Csaba. 1983. Üzletközpont a Váci utcában. Népszabadság, 41(157), p. 8.

41 Architect György Vedres died in 1987 aged 52, the year the author of this paper was born. Sadly, also the architects József Schall (1989) and Miklós Kapsza (2007) were also deceased by the time of the start of the research.

42 The abstract pattern and the paving have been since removed.

43 [Lit.: metalworker]. The firm specialized in metal facades and constructions, among them the facade of the Centrum Warenhaus in Dresden, Germany, designed by Hungarian architect duo Ferenc Simon and Iván Fokvári (1968–1970) and constructed in 1973–1978.

44 WOLFRUM, Sophie and JANSON, Alban. 2019. The City as Architecture. Basel: Birkhauser, p. 94.

45 Benjamin, W., 2023, p.10.

46 Wolfrum, S. and Janson, A., 2019, p. 94.

47 WALTER, Benjamin. 2002. The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 13.

48 SPENCER, Douglas. 2017. The Architecture of Neoliberalism. How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, p. 1.

49 Spencer, D., 2017, p. 56.

50 Fisher, M., 2009, p. 16.

51 “Transparent werden Dinge, wenn sie Negativität abstreifen, wenn sie geglättet und eingeebnet werden.” HAN, Byung-Chul. 2012. Transparenzgesellschaft. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, p. 5.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.2

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License