Eva Hollo Vecsei (1930), a pioneering Hungarian architect who emigrated to Canada in 1956, became a significant figure in Québec’s modern architecture. Despite her achievements, her contributions remain largely unknown in Europe. This paper offers a biographical analysis of her modernist architectural oeuvre, initially shaped in Hungary under socialist-realist mandates before 1956, and later in Canada, where she gained prominence for her megastructures, particularly associated with the 1967 Expo in Montréal. Drawing on archival research and interviews, the paper explores the conditions that facilitated her success, the constraints she navigated, and the challenges she faced as a woman émigré in the male-dominated architectural profession of her time.

Introduction

Eva Hollo Vecsei1 is one of the most successful Hungarian architects abroad in terms of architectural scale and professional recognition. Her career spanned two distinct architectural contexts: socialist Hungary (until 1956), where she was regarded as a promising young architect2, and Canada (from 1957), where she became one of Montréal’s leading modernist practitioners. Despite her canonical status in Montréal’s architectural history, her contributions remain unacknowledged in Hungary. This paradox raises critical questions about the recognition of émigré architects and how migration shapes professional trajectories. Eva Hollo Vecsei’s lifework offers a valuable case study for understanding these dynamics, particularly concerning gender and transnational knowledge transfer.

Beyond describing her architectural oeuvre, the study explores three central questions: How did Vecsei’s migration shape her professional trajectory? What constraints and opportunities did she face as a female architect and an émigré? How did her Hungarian architectural background influence her work in Canada? Rather than merely recovering her name for (Central) European architectural history, this article examines the structural and professional dynamics that influenced her career. It highlights how she navigated different architectural and political systems, adapted to new professional environments, and contributed to the built environment through large-scale projects such as Place Bonaventure (1964–1967) and La Cité (1973–1977).

Intersecting structural conditions – including Cold War-era migration and exile, the professionalisation of architecture in Canada, and gendered barriers within the field – are what shaped Vecsei’s career trajectory. This paper argues that gender remains a critical lens for understanding how 20th-century women practitioners like her navigated and narrated their careers within a historically male-dominated profession. Rather than reviving essentialist distinctions, such as the reductive category of “female architecture”, the study situates Vecsei’s professional legitimacy within the broader gendered conditions of architectural practice, emphasising how her self-articulated focus on recognition and accomplishment reflects – and critiques – the institutional and cultural barriers of her time.

Vecsei’s career exemplifies these complexities: while she rejected essentialist notions of “female architecture,” she strategically positioned herself within the profession, responding to gendered obstacles with distinct professional stances. Like many of her generation, she was deeply committed to the ideal of gender equality, yet her career path appears pioneering and exceptional from today’s perspective. Her work in Socialist Hungary and Canada reflects a negotiation between structural constraints and personal agency, illustrating how women architects navigated and reshaped their field.

The paper also examines the intersectionality of Eva Hollo Vecsei’s position as both a woman and an émigré. This dual status brought advantages and disadvantages, shaping her professional trajectory in complex ways. On the one hand, her Hungarian background equipped her with technical expertise in large-scale urban design and concrete construction, honed through projects like housing developments for miners, skills that became pivotal in her integration into Canadian architectural practice. On the other hand, her status as a newcomer presented barriers to professional recognition, particularly in the male-dominated Québec architectural circles of the 1960s and 1970s.

This study is methodologically grounded in biographical analysis, drawing on interviews, archival research, and project documentation. It follows a primarily biographical structure, centering on Vecsei’s individual experiences and career, based on interviews and email correspondence conducted with her between November 2023 and January 2025. While such an approach offers valuable insight into her trajectory, it also presents critical challenges. Biographical narratives, particularly in architectural historiography, have long been shaped by the myth of the solitary genius, often male, whose exceptionalism overshadows the various forces at play. Simply inserting women into this framework risks reinforcing the paradigms that have historically excluded them. To counter this to some extent, the study deliberately situates Vecsei’s work within the institutional and professional contexts that influenced her development. In doing so, the study draws on secondary literature. It examines the gendered dimensions of the environments in which Vecsei operated, particularly during her early years in Montréal. It contextualizes her experiences alongside other Eastern European women, referred to as the “Québec pioneers”,3 in the 1960s.

At its core, however, the study is neither an exhaustive analysis of women in architecture across the varied contexts in which Vecsei worked, nor a methodological proposition for writing about gender in architecture. Instead, it primarily aims to trace Vecsei’s career and architectural contributions across shifting political and professional landscapes. In doing so, it foregrounds the challenges she faced, her strategies, and the structures she navigated as a woman practicing architecture in postwar Hungary and Québec’s architectural milieu. While the study remains focused on her individual trajectory, it necessarily intersects with broader discussions on gender, migration, transnational knowledge transfer, and the role of professional networks in shaping architectural practice. Ultimately, it situates Vecsei’s work within a transnational history of modern architecture, emphasising her influence on the built environment as shaped by – and responsive to – both her Hungarian and Canadian experiences.

Her Early Career in 1950s Hungary: Promise, Constraints and Education

Education and the Path to Architecture: “Make the Real Thing, Architecture”

Eva Hollo Vecsei was born on 21 August 1930 in Vienna and grew up in Budapest. Her early years unfolded under political constraints – her family, socialist émigrés, fled the Horthy regime only to face new restrictions upon returning to Hungary in 1933. Her father, barred from practising law due to anti-Jewish laws, took a lower-ranking position, and the family lived modestly in a courtyard apartment. Postwar restructuring altered their circumstances when he was appointed director of the National Social Insurance Institute [Országos Társadalombiztosító Intézet – OTI].4

By the age of nine, at the outbreak of the war, she had made a decisive vow never to speak German again – war and the Holocaust left lasting imprints. Survival depended on a Swedish safe conduct pass provided by Raoul Wallenberg and refuge in a protected house.5 Yet her artistic education persisted, funded by her grandmother, who had been deported to Auschwitz.6 Even during the war, she attended the Jaschik Álmos Drawing School, where she trained in freehand illustration and mastered precision with graphite, a skill set that later became foundational.7

Literature and music dominated her family life – architecture was absent. However, she was captivated by the visual spectacle of opera stage sets, initially leading to aspirations in set design. By 1948, political realities intervened again. The Iron Curtain foreclosed any opportunity to study at the Reinhardt Seminar in Vienna.8 A friend’s pragmatic advice shifted her course: “You won’t just make sets; you’ll make the real thing!”9 Architecture, merging technical rigour with artistic expression, became her discipline. Her aptitude for precision drawing and spatial reasoning ensured her success at university.

A Strong Foundation Amidst Political Constraints:

Modernist Influences Within Socialist Realist Mandates

Vecsei pursued her studies at the Budapest Technical University, then Hungary’s sole architectural training institution. This university was the alma mater for many architects who later emigrated following the Revolution of 1956.10 Her time at the university, from 1948 to 1952, coincided with profound political and cultural change. The consolidation of the communist regime in 1948 led to the nationalisation of the construction industry and a restructuring of architectural education to align with the ideological demands of Socialist Realism.11 The curriculum was reshaped to enforce political conformity, with faculty members selected based on political loyalty.12

In 1951, after the “Great Architectural Debate,” Socialist Realism became the official architectural style in Hungary. This shift marked a clear rejection of Modernism, which had gained prominence since the late 1920s. Students were now required to base their designs on Hungarian Classicism and the national renewal movement of the 19th century, with classical ornamentation becoming mandatory in architectural design tasks. All semester projects and diploma work were evaluated on their adherence to Socialist Realist principles.13

In response to these constraints, Vecsei strategically chose to design a circus building for her diploma project. She reasoned that, due to its unique function, a circus would be exempt from Socialist Realist critique: “I chose it because a circus is a structure… it has a completely different function, so it couldn’t be criticised for not being Socialist Realist”.14

Although the period between 1946 and 1956 was marked by constant change and political influence over architectural education, some traces of Modernist principles persisted. Karácsony and Vukoszávlyev (2019) suggest that despite the dominance of Socialist Realism, certain Modernist elements remained in the curriculum.15 One significant influence was Scandinavian Neoclassicism, which had been integrated into Hungarian architectural education since the interwar period. After World War II, Hungarian architects who had found refuge in Denmark brought back Scandinavian professional literature and ideas, spreading them among students and colleagues.16 Vecsei’s exposure to the Danish style under the mentorship of Károly Weichinger, who admired Gunnar Asplund’s work, influenced her later designs, such as her plans for the Lágymányos housing estate.

One of Vecsei’s early projects, a design for a temporary student dormitory, received high praise from her mentor Weichinger, who remarked that she was already “a fully trained architect” and might not need to continue her studies.17 In addition to architectural training, students at the Technical University received a rigorous art education, with specialised classes in drawing and watercolour being key to developing design skills – an area in which Vecsei excelled. Throughout her years at the university, Vecsei was mentored by notable figures, including Weichinger, Tibor Kiss (with whom she worked as an assistant), and Pál Csonka. Despite the dominance of Socialist Realism, civil engineering and architecture students received a strong foundation (“solid base”)18 in building construction and structural engineering under Csonka, which prepared them for their careers, whether in Hungary or abroad.

Female Representation and Professional Challenges in the 1950s Architecture Faculty:

Structural Conditions for Women at Hungary’s Technical University

At the Budapest University of Technology (BME), Eva Hollo was one of only ten women among a cohort of 120 students, a situation she recalled clearly. Initially, pursuing higher education had not occurred to her, as architecture was not yet considered a conventional career for women. Although access to technical education for women had gradually expanded since 1912, systemic barriers remained entrenched. A law passed in 1946 ensured equal university admission for women, yet their representation in architectural education remained notably low. The establishment of an independent Faculty of Architecture in 1950 contributed to a significant increase in student enrolment, and the postwar construction boom, driven by reconstruction efforts, industrial projects, and large-scale housing initiatives, further encouraged women to pursue technical studies.19

At the university, Vecsei met her future husband, André Vecsei. The couple graduated in 1952, and shortly thereafter, they exchanged rings at City Hall.20 Upon completing her diploma, Vecsei became an assistant to Professor Tibor Kiss in 1952. However, the role was incredibly demanding, requiring attending university lectures and participating in evening classes designed for workers. This resulted in 12-hour workdays, which became increasingly difficult to sustain after the birth of her child.21 Following Andrea’s birth, Vecsei moved to Housing and Communal Building Design Enterprise [Lakó- és Kommunális Épületeket Tervező Vállalat – LAKÓTERV], active from 1953 to 1992, where the work environment was more family-friendly.22 She was allotted time for breastfeeding in the mornings, which allowed her to begin her workday later. Her mother-in-law also played a crucial role in managing the household, and the family employed a housekeeper for a period.23 Eva and André Vecsei had two children together: Andrea, who also became an architect, and Paul.

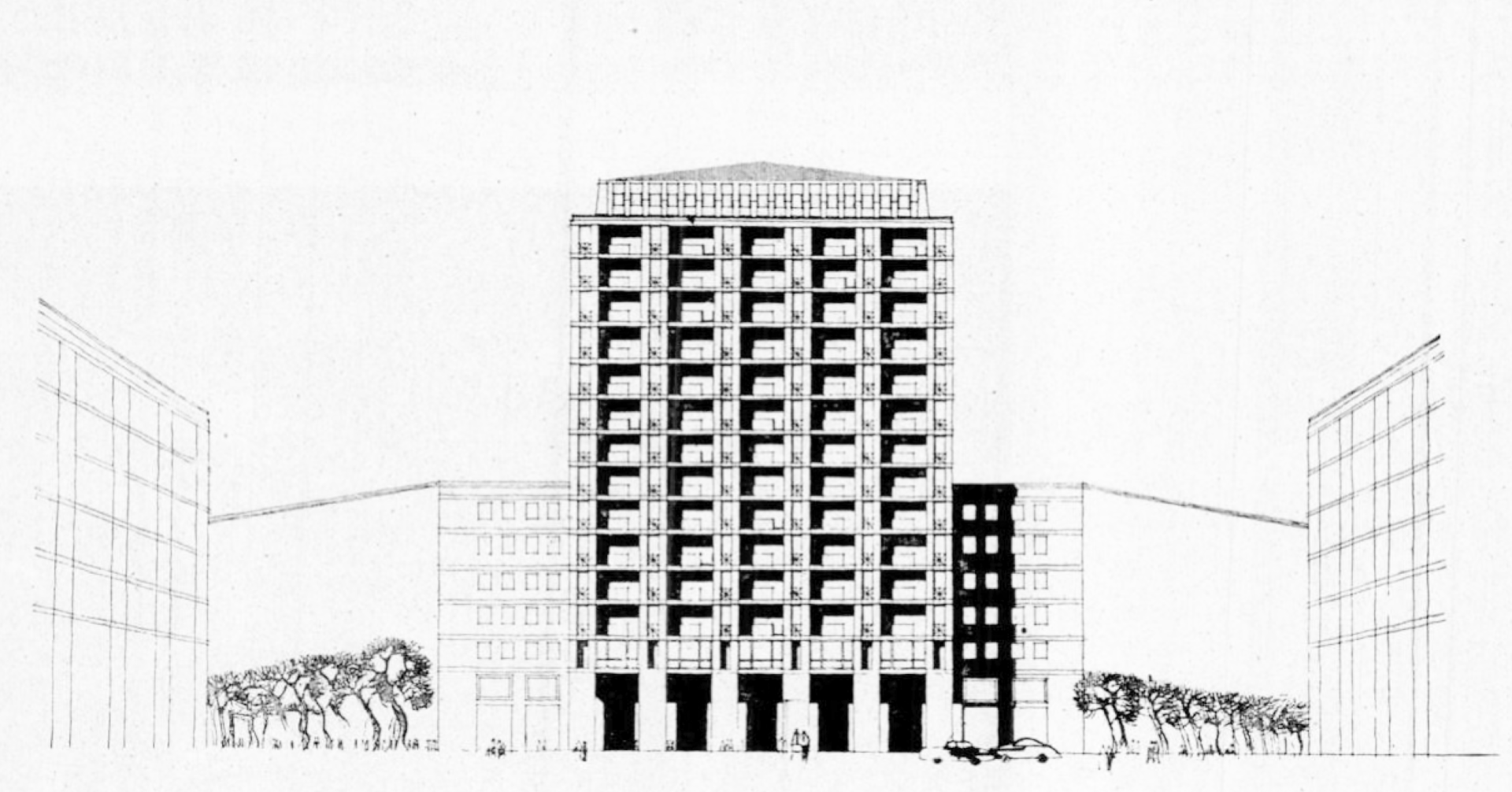

Key Projects and Architectural Practice in Hungary

At LAKÓTERV, Vecsei worked closely with József Körner, a prominent party member and leader often occupied with various responsibilities. As a result, Körner entrusted Vecsei with most of the design tasks.24 Their working relationship was mutually beneficial, as Vecsei reflected, “It was very good, we both did well. He received the credit, and I did the work, but he never took it himself.”25 In Socialist Hungary, state institutions heavily influenced architectural practice through directing construction projects, enabling significant state-supported housing developments and providing excellent training for Vecsei. One of her first major projects was the design of point houses for miners in Tatabánya. In this project, she advocated for improved living conditions by ensuring that they received separate bathrooms, deviating from the original plan that only included a shared bathroom in the hallway. Vecsei’s next significant task was the design of a 14-story modern high-rise as part of the larger urban development plan for the Lágymányos housing estate, along with a primary school, which remains the only building she designed still standing today in Hungary. In the context of the time’s political constraints and architectural mandates, this design represents an example of modernist influences within the confines of socialist realist ideologies, as discussed in Chapter 2.2. Her designs displayed the influence of Danish architectural traditions, which she had absorbed during her university years. The emphasis on functional and efficient design and integrating social considerations into the architectural process remained central to her practice throughout her career.

Emigration: The Impact of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution

In the final days of the 1956 Revolution, before its suppression by the Soviet military intervention, tens of thousands of Hungarians fled to the West, including approximately 150 qualified architects and architecture students.26 Among them, Eva Hollo Vecsei and her husband, André, decided to emigrate: “We simply decided that we would not be cowards and would face life’s challenges. We saw it as an adventure, though we were concerned about the child,”27 Vecsei recalled. Despite the enforced socialist realist style (1951–1955), the educational framework at the Budapest University of Technology preserved elements of Modernist principles, enabling these émigrés, including Vecsei, to integrate smoothly into the broader international Modernist architectural context.28

Eva Hollo Vecsei and her husband left Hungary with their infant daughter in secrecy to avoid detection: hidden among the passengers of a train bound for the West, they managed to cross the border into Austria.29 The crossing was tense, and though they were fearful, they managed to escape, carrying only the essentials. In Austria, they spent time in a refugee camp, and after a brief stay, the couple decided to move on. They sold Eva’s diamond ring to fund the next stage of their journey, eventually reaching Vienna. After twenty years, Vecsei found that her German language skills were returning, feeling as though “a drawer in my mind opened.”30 From Vienna, with the help of friends and the Canadian embassy, they secured papers to emigrate to Canada after spending a short time in the Netherlands, where she worked on a hospital design in Maastricht. She recalled the oddity of their situation, mainly when they encountered a group of deeply religious Catholics in the southern Netherlands who suggested that she should focus on having more children and not work – an outlook she rejected. “They described everything I didn’t want from life,” Vecsei said. “We thanked them and left. So that was it,”31 she recalled of their departure. They finally made their way to Canada. Though they were initially supposed to head to Winnipeg, André’s fluency in French impressed the border officials, and they were redirected to Montréal instead.32

Settling in Canada: Transition and Integration into the Profession;

Male Domination in Québec’s Architectural Practice in the 1960s and 1970s

Vecsei’s initial impression of Montréal was far from positive. Compared to Budapest’s cultural richness, the city appeared overwhelmingly industrial. “There was nothing- no proper theatre, opera, or concerts. The waterfront was ugly and entirely industrial. The bridges were unattractive. My first impression wasn’t good. But we thought, ‘There’s a lot of work here’,” she recalled.33

Starting that work seemed rather difficult. Although she was already an established architect in Hungary during the 1950s, she faced significant challenges as an immigrant woman in Montréal. Compared to socialist countries, where women were encouraged to participate in male-dominated fields, Canada’s architectural profession remained largely male-dominated. Even during the 1960s, trained female architects were often met with suspicion or outright resistance: “When I arrived in Montréal, I was shocked by the hostility I encountered while job hunting: ‘You’re a married woman with a child, and you want to work?!’ – she recalled.

Vecsei’s experience was not unique; her experience reflected a broader pattern among women who had begun their architectural education in countries such as Greece, Hungary, or Lithuania, where gender parity in the profession was more advanced.34 Many of these émigré architects struggled with the perception of architecture as a male domain. One such woman recounted: “I thought there was something wrong with me. I couldn’t understand their attitude. Especially coming from Greece, where it was normal for women to be in architecture… half of the students in architecture were women, even in 1946”35 Unable to secure an architectural position in this unwelcoming climate, Vecsei initially worked as a draftsperson, producing technical drawings – a role well below her qualifications but one that allowed her to gain a foothold in the Canadian architectural scene.

After two years, with the support of her husband, she secured a position at ARCOP (Architects in Cooperative Partnership) & Associates, a firm known for valuing talent regardless of race, religion, or gender.36,37 She began with a two-week trial period, a crucial turning point in her career, as it allowed her to work on large-scale projects where she proved outstanding.38 Initially, she hesitated to work alongside her husband, fearing that people would assume she was merely his assistant. Two years later, her husband founded his firm with friends.

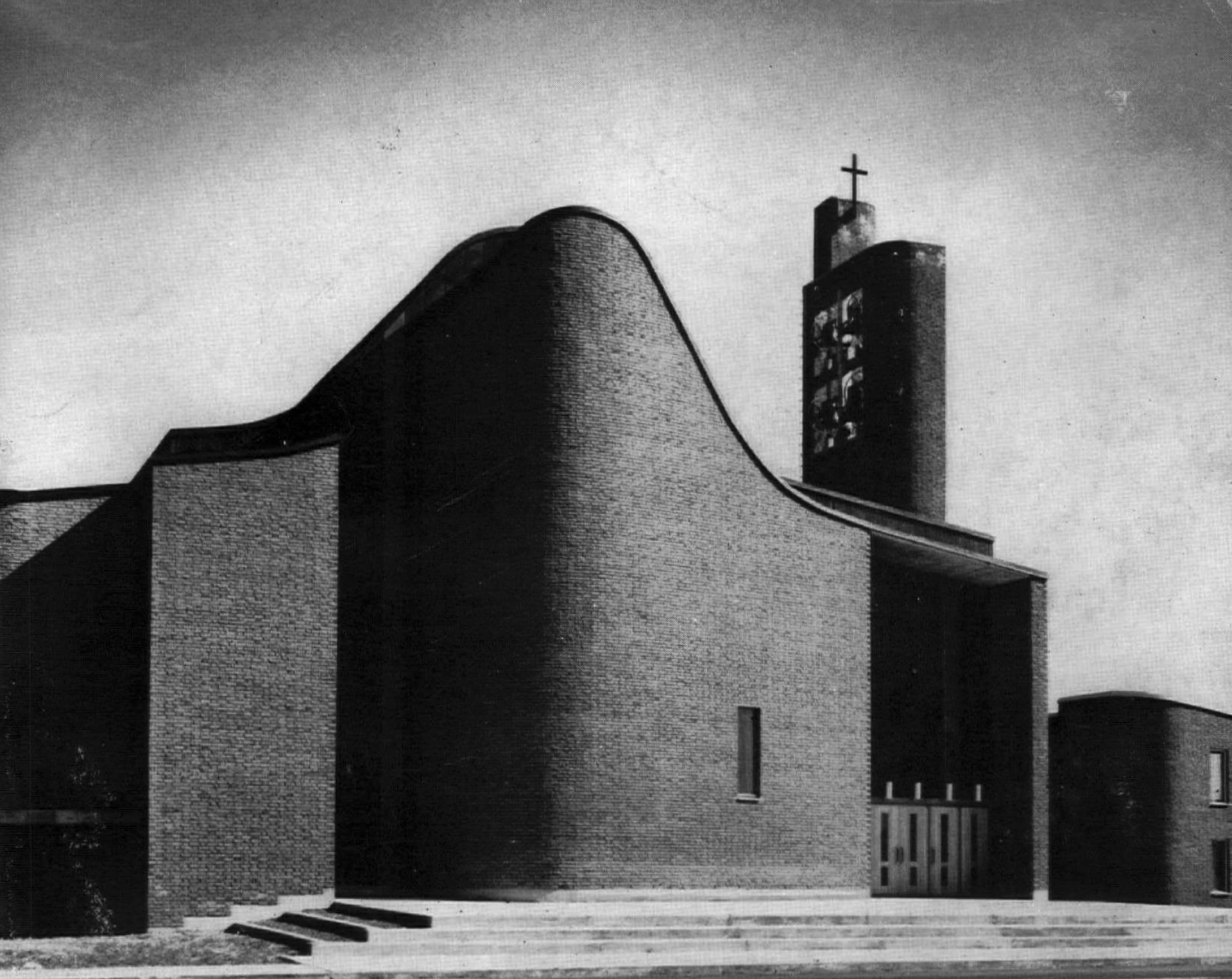

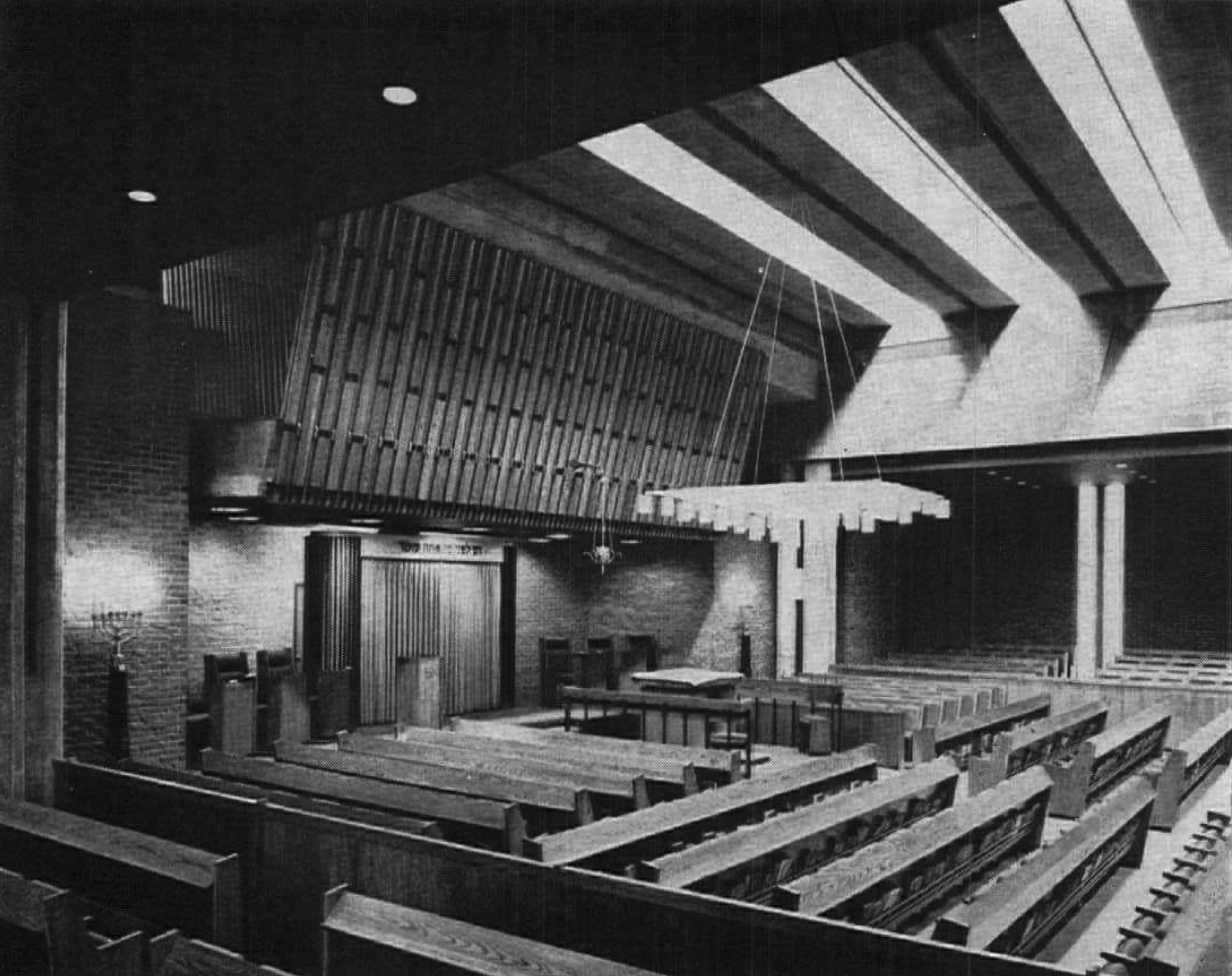

Although the article primarily focuses on Vecsei’s large-scale projects, it is essential to highlight the diversity of her work. During her thirteen years at ARCOP, she contributed to numerous projects, several of which were awarded the prestigious Massey Medal. These include the Tifereth Jerusalem Synagogue, Côte-Saint-Luc, Québec (1959–1971); Saint Gerard Magella Church, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Québec (1960–1963); Laval Civic Centre: Town Hall and Police Station, Laval, Québec (1962–1965); Georges Frédéric Pavilion, Drummondville, Québec (1963–1965); Place Bonaventure, Montréal, Québec (1964–1967); the Student Union Building, McGill University, Montréal, Québec (1965); Saint Thomas d’Aquin Church, Saint-Lambert, Québec (1965–1967); the interiors of Killam Library, Halifax, Nova Scotia (circa 1966–1971); and the Life Sciences Building, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia (1971).

The Québec Pioneers – Women from Eastern Europe

Annamarie Adams, an architectural historian, examines the role of female architects in Canada in Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession, co-authored with Peta Tancred. Among them, Eva Hollo Vecsei emerges as a key figure in shaping modern architecture in Québec, not only because of her professional achievements but also due to three defining characteristics she shared with many other so-called Québec pioneers: her Eastern European origins, the significant experience she gained at ARCOP, and her deviation from the conventional gendered path of designing domestic-scale commissions.39

Labour shortages initially drove women’s entry into the architectural profession in Canada during World War II, which created previously inaccessible openings. These shifts offered women new opportunities, particularly in the emerging field of city planning in the 1940s and 1950s – a sector still unbound by the entrenched traditions of architecture. As Blanche Lemco van Ginkel, a pioneering architect involved in Expo 67 and the first female Dean of Architecture at the University of Toronto (appointed in 1977) reflected, several women, including herself and Catherine Chard, found employment more readily in urban planning than in architecture, in part because figures like Eugenio Faludi40, whose background was European, were more willing to hire women in this new and evolving field.41

Adams and Tancred argue that the case for women architects in the development of Modernism was, in fact, largely contingent on the influx of women architects from other countries after the war.42 Based on their interviews with pre-1970 entrants, they found that twelve of the eighteen early Ordre des architectes du Québec registrants were born abroad, with no fewer than seven hailing from Eastern Europe.43 The impact of immigrant female architects on modern architecture depended primarily on how successfully they integrated into the profession upon arrival. Those from countries where women had already secured a foothold in architecture brought technical expertise, particularly in high-rises, public buildings, and office complexes, that positioned them advantageously in Montréal’s male-dominated architectural scene.44 Their influence often surpassed that of their Canadian-born, English- and French-speaking counterparts, similarly to the United States, where several of the most prominent female architects to rise to prominence after World War II were born and raised and educated outside the USA, – such as Denise Scott Brown (born in Zambia, raised in South Africa and educated in Europe and later in the USA), Susana Torre (born, raised and educated in Argentina).

ARCOP, the office where Eva worked, played a pivotal role in the early careers of female architects in Québec.45 Key figures such as Dorice Brown Walford, Tiuu Tammist O’Brien, and Pauline Clarke Barrable were part of the team. Barrable later became a senior architect for the Royal Bank of Canada.46 Sarina Katz, originally from Romania, also worked at ARCOP before joining Moshe Safdie’s team for the Habitat projects.47 Her career took her through several prominent offices, where she worked on various large-scale designs. Thus Vecsei entered the Canadian architectural field at a time when female architects were rare, and the lead-up to Expo 67 in Montréal gave these immigrant women crucial opportunities to establish themselves.48 According to Adams, “no other woman in Québec in the immediate post-war period had the range of experiences that Vecsei brought to Place Bonaventure.”49

She was drawn to the complexities of large-scale projects. In a 1965 interview with the Montreal Star, she rejected gendered expectations of her work, a stance was emblematic of many Québec women architects in the 1960s50: “Please don’t put me in the category of women who add their little pink touches… I’m not interested in home-building projects that are uniform and repetitious… Huge massive structures that allow for individual expression and require complex solutions to integrated problems excite me.”51

Vecsei’s Hungarian background proved to be both an asset and a liability. Socialist Hungary’s practice in robust steel and reinforced concrete, emphasising grid-based layouts, contrasted sharply with Canada’s reliance on wood. Her expertise in reinforced concrete structures was considered advanced in Canada, where such techniques were not yet mainstream. Yet, while technically well-equipped, she lacked the North American instinct for self-promotion and networking, crucial for career advancement.52 Additionally, she had to navigate the practical hurdle of adapting to the imperial measurement system then still in use, a fundamental shift from the metric standards she had used in Hungary.

The first Major Breakthrough – Place

Bonaventure as an Experimental Project;

Its Role in Montréal’s Urban Landscape

One of the key architectural projects in preparation for Expo 67 was Place Bonaventure (1964–1967), a significant commission for Vecsei in Canada, undertaken in collaboration with architect Raymond T. Affleck. This project stands out among the previously mentioned works due to its scale and complexity. Strategically located along Montréal’s north-south downtown axis, the building stands among key modern structures such as Place Ville Marie (I. M. Pei and ARCOP, 1957–1966) and the Queen Elizabeth Hotel (George Drummond and Harold Greensides, 1958). This area gradually became the new urban core, shifting the city’s development away from its earlier east-west orientation structured around Dorchester Boulevard (now René Lévesque), Saint Jacques, and Saint Catherine streets.53

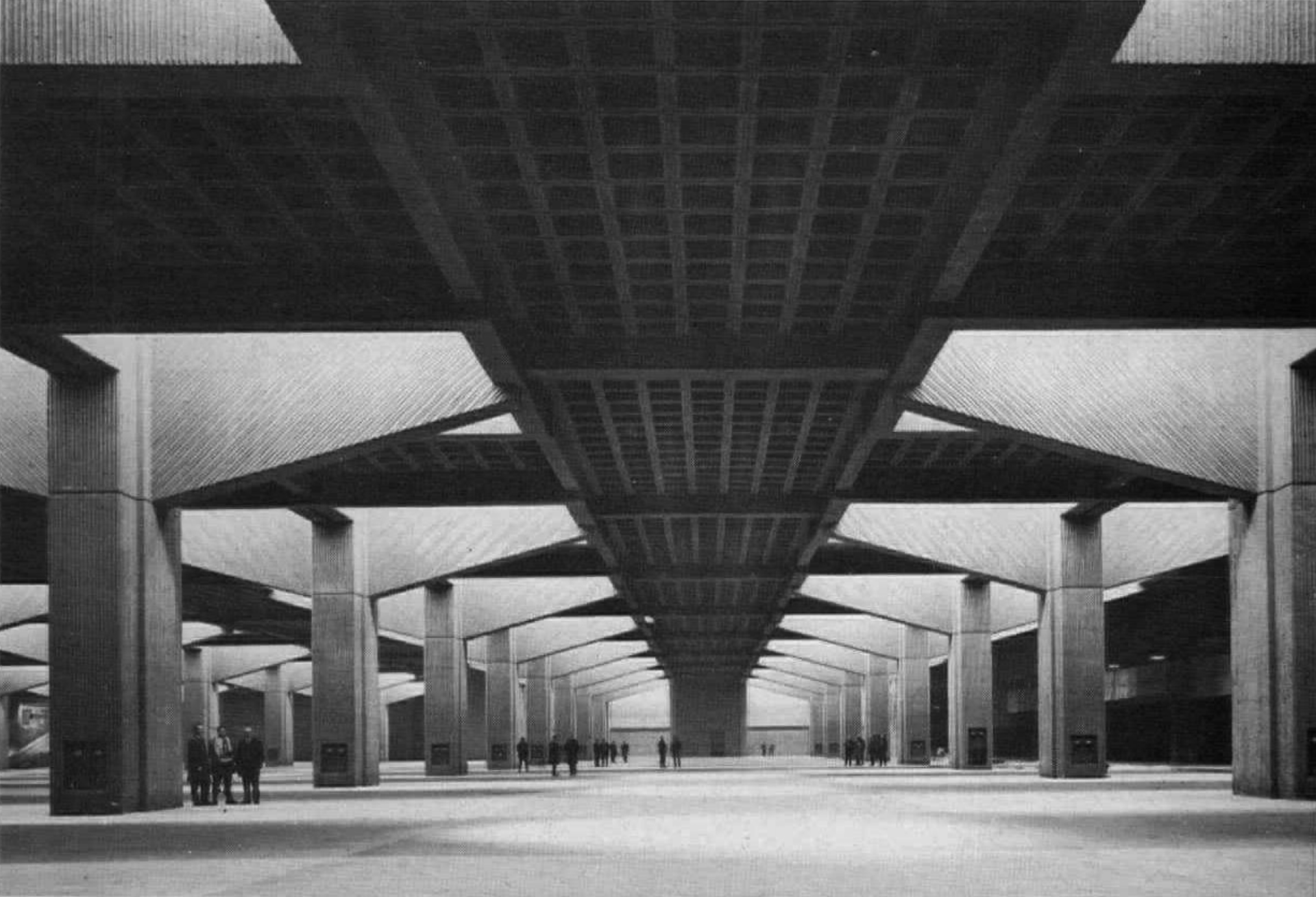

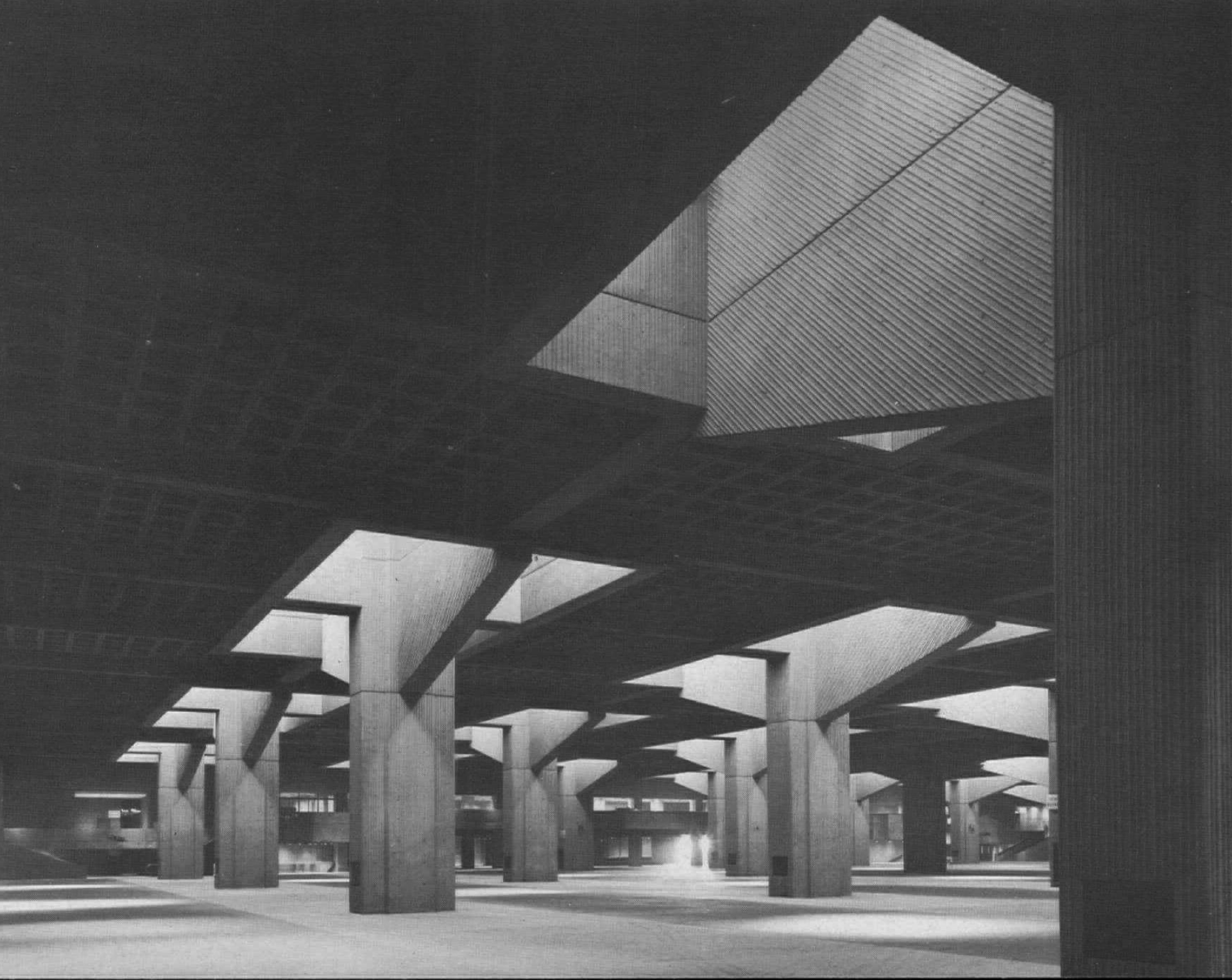

At its completion in 1967, Place Bonaventure was among the largest buildings on a global scale, with nearly 100,000 m² of leasable space, approximately 10,000 m² of office space, and an 18,580 m² exhibition hall. Designed as a multi-functional commercial complex, it integrates various urban functions within a single structure, incorporating an exhibition hall, retail spaces, and a hotel. The project’s approach reflected the broader urban vision of integrating transport, commerce, and leisure, linking directly to the metro, railway, and pedestrian networks.54 A notable innovation was the building’s rooftop, which featured one of Montréal’s first green roofs – a designed landscape with a garden and a four-season pool that introduced a new approach to utilising rooftop spaces in dense urban environments.

Banham underscored Place Bonaventure’s identity as a megastructure, illustrating its convergence of pedestrian and Metro infrastructure: “The point at which the two perspectives on Montreal actually meet at right angles, where the pedestrian plumbing and the Metro intersect and the whole promise of a subterranean city protected from the elements comes closest to realisation, is Place Bonaventure. Located at the first point where the Metro can comfortably squeeze under the CNR, which is also the point where the pedestrian plumbing would naturally break out to the surface, Place Bonaventure is, appropriately if disputably, a megastructure in itself.”55

As an economical and practical building material, concrete influenced the structure’s overall form. The material allowed for expansive interior spaces while contributing to the building’s fortress-like appearance. The ribbed concrete surfaces recall the work of Paul Rudolph, whose brutalist designs were widely discussed in architectural discourse at the time. Eva Hollo Vecsei was particularly interested in how the building’s massing and detailing shaped its visual impact. She carefully designed the articulation of the corners, using mechanical towers to create a rhythm in the façade. The journal Architectural Record noted this feature as a refinement of the building’s overall composition.56 The brutalist character of Place Bonaventure aligns it with the monumental concrete works of Paul Rudolph, Ulrich Franzen (Cornell University’s Uris Hall, 1968), and I. M. Pei (National Center for Atmospheric Research, Colorado, 1966–1967).57

Structural Considerations and Design Innovations

The Canadian National Railway (CNR) made the site available for development in 1963, with preexisting structural provisions incorporated into the rail platforms to facilitate future construction. Construction began in 1964, with completion scheduled for 1967. The engineering solutions had to accommodate uninterrupted railway activity because train operations continued beneath the site throughout construction. This constraint influenced the building’s structural logic and organisation.

The vast exhibition hall, spanning four acres, was designed with 12-meter-high columns arranged in a 7.5 x 22.5-meter grid, aligning with the railway’s loading platforms below. Supporting the building’s upper eight levels, the columns branched out to form a denser 7.5 x 7.5-meter grid – evoking Indigenous totem poles, as she recalls, a reference further emphasised by the textured concrete surfaces. In her 1993 reflections, Vecsei described this as an expression of structural logic rooted in the first constructivist architectural tradition: the Gothic. Ironically, one of the most memorable praises she received was: “Your architecture is exceptionally masculine.”58

One of the defining features of the project was the rooftop garden. Vecsei envisioned this space as an integral architectural element rather than an afterthought. “Creating a green oasis in downtown Montréal – where half the hotel rooms overlooked a garden featuring waterfalls, rock formations, trees, and a four-season pool – was a radical innovation in the 1960s,”59 she later remarked. This concept of the “fifth façade” – where the roof serves as an active urban space – became a recurring theme in her later projects. The Bonaventure Hotel’s green roof was one of Canada’s earliest instances of integrating landscape architecture with high-density urban development.

The Design-Build Process: New Methods and a New Pace

Place Bonaventure introduced Vecsei to the design-build model, which differed from the traditional division of roles in architectural practice. The process involved continuous adjustments during construction, requiring direct collaboration with contractors and developers. Pauline Barrable, another architect working at ARCOP, recalled the rapid pace of design changes: “You would literally do a drawing on the board and then pick it up off the board and run across the street… and say ‘build this’ and they literally would pour the concrete.”60

For Vecsei, the experience was marked by the challenge of navigating a male-dominated professional environment. As the only woman architect participating in the weekly project meetings, she described the setting as intimidating. To manage the pressure of these high-stakes discussions, she took Librium, a sedative medication – a detail that underscores the demanding atmosphere. The Bonaventure project, carried out by the ARCOP office, was a collaborative effort involving a team of architects, engineers, and planners. Vecsei emphasised that the work was collective and that the project’s success depended on close coordination among the various professionals involved. Within this framework, she played a central role and the project allowed her to demonstrate “her own geometric and spatial skills, her knowledge of architectural form and theory, and the power to coordinate, integrate and synthesize the knowledge of others”.61

Her work on Place Bonaventure was widely recognised, contributing to her reputation as an architect capable of working at an urban scale. When she was named an honorary fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1990, her architecture was acknowledged for “transforming modernism into an expressive, contextual, and symbiotic language.”62 She remains the only Canadian woman in Contemporary Architects (1980), alongside eleven Canadian men. Her role in Place Bonaventure established her as a significant figure in Canadian modernism, with her work documented in international architectural publications and exhibitions.63

La Cité, Montréal

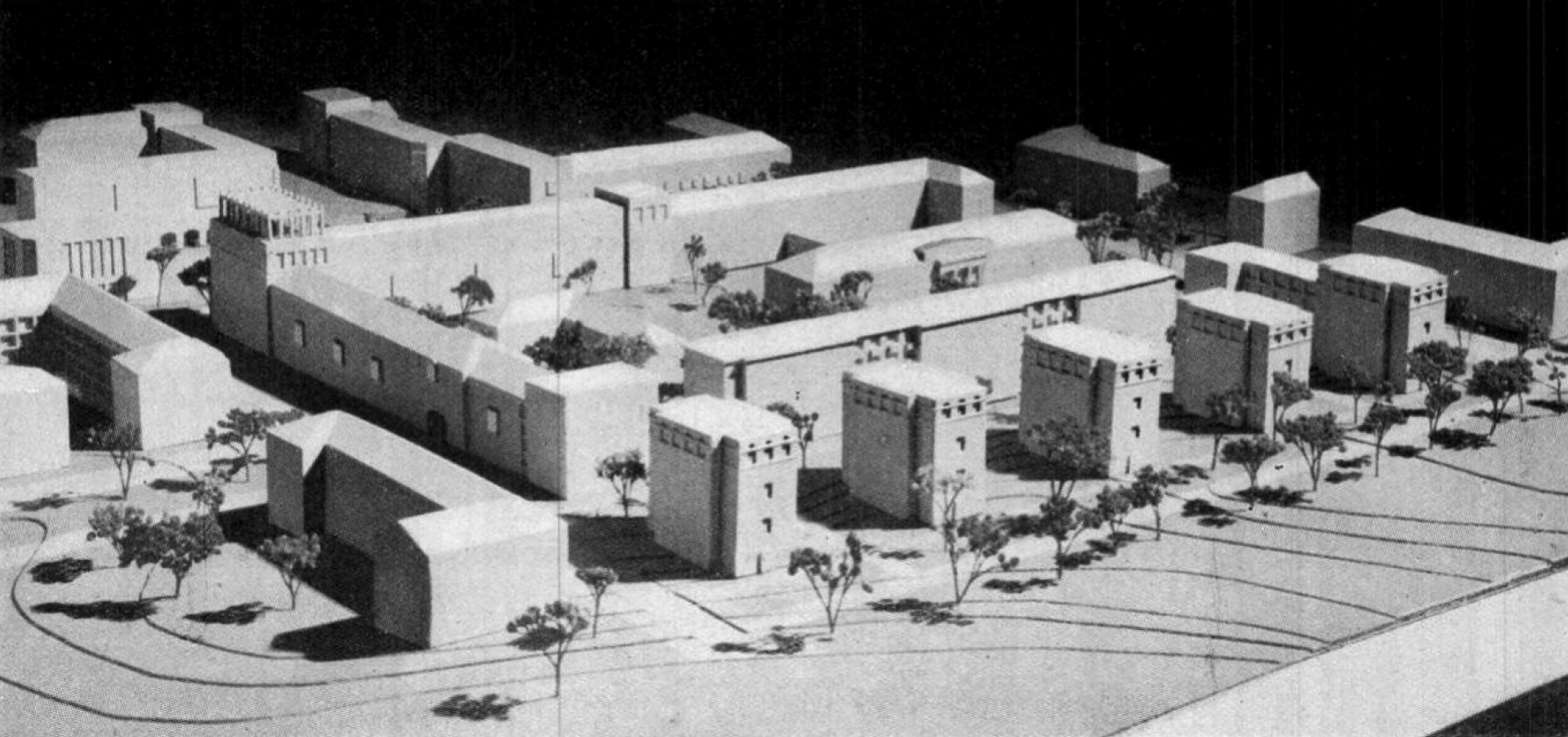

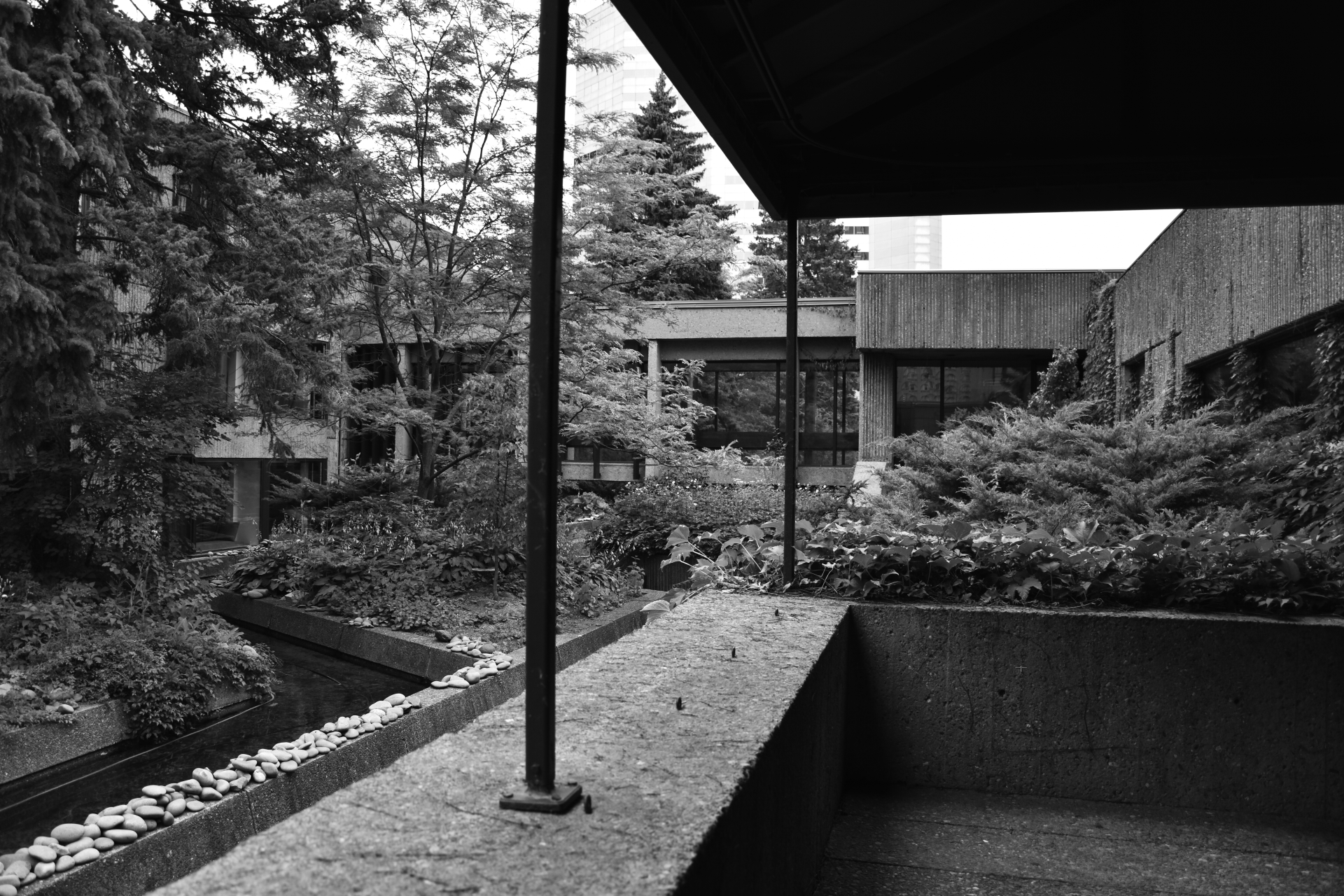

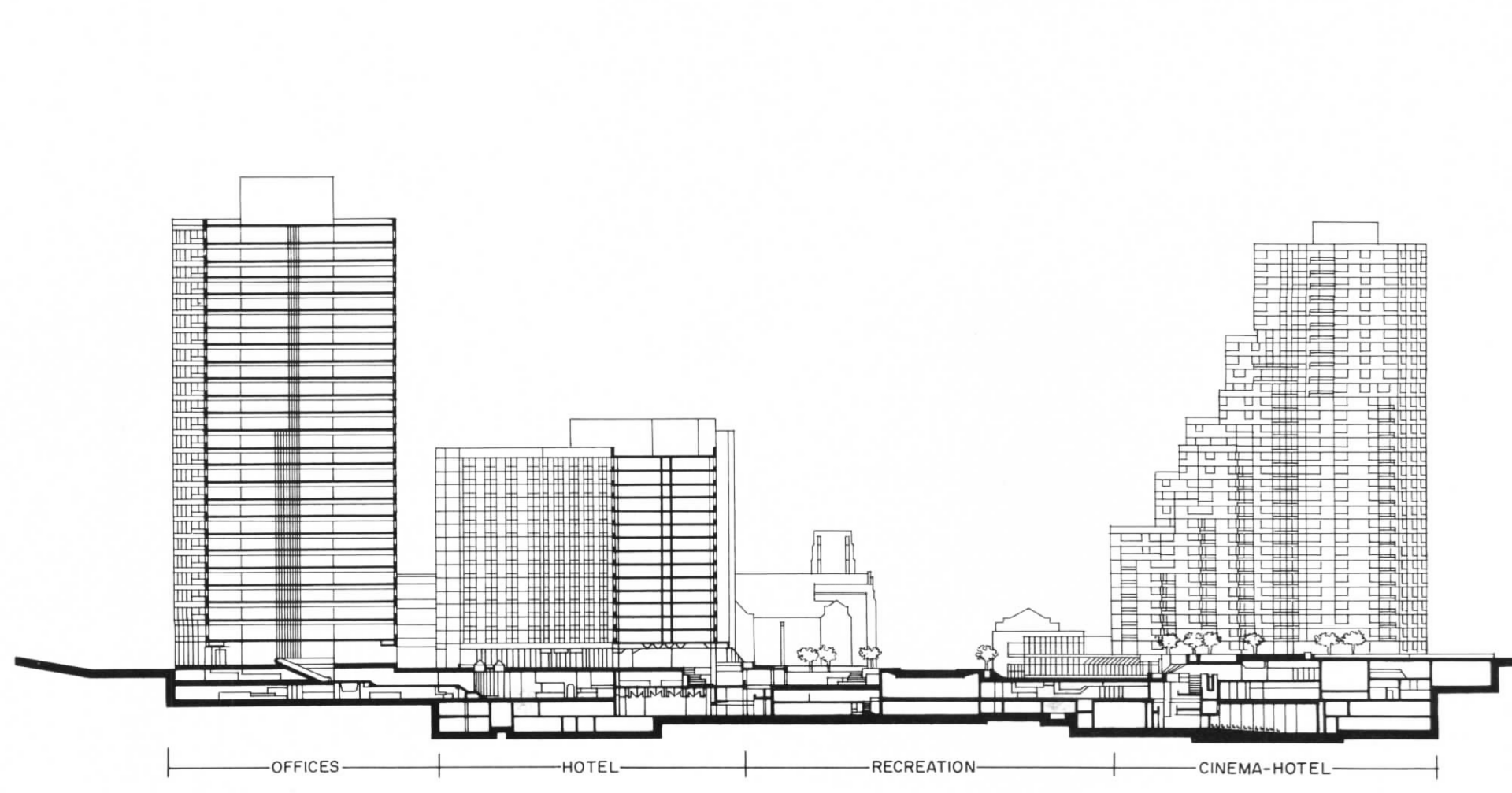

After completing Place Bonaventure, Vecsei’s next major project was La Cité (1973–1977), a multifunctional building complex in downtown Montréal. With a budget of $120 million, the complex was completed in time for the 1976 Olympics. Spanning 2.8 hectares and covering four city blocks, La Cité created a unique communal space accommodating around 3,000 residents. The development included 500 hotel rooms, 1,200 residential units, a landscaped rooftop terrace with trees and a pool, 18,580 square meters of commercial space, an underground grocery store, a fitness club, a cinema, and a two-story parking structure.64

What truly distinguishes La Cité is its stepped design, ranging between 24 and 6 stories. From the perspective of the main façade, each step reaches a maximum height of four stories, reflecting the scale of the surrounding streets. The 24-story towers align with the city block, while the stepped structure’s final 4-story section matches the scale of the Victorian homes on the opposite side. The lower four-story step rises naturally from the street, not separated from it, offering a seamless connection to the urban fabric. Balconies and terraces further fragment the facades, giving the complex a layered, dynamic quality.

The arrangement of the three residential towers was designed to ensure that each building would receive optimal sunlight while allowing residents to enjoy the green spaces within the complex. The connections between the three towers are realised through various communal spaces: numerous community services are offered on the ground floor, while the basement houses shops and entertainment functions. The underground infrastructure beneath the complex facilitates transportation links, providing easy access for residents and workers to all of the site’s services.65

Eva Hollo Vecsei took over the project’s management in 1973 after founding her firm in Canada. The realisation of La Cité was met with resistance, particularly from opponents of high-rise buildings who wished to preserve the city’s low-rise architecture. The debates even drew in urban preservationist Jane Jacobs, fuelling many heated discussions. In this sense, La Cité also symbolises the tension between modern urban development and the preservation of a city’s historical character. This is particularly intriguing given that she is archived in the Canadian Centre for Architecture, an institution founded by Phyllis Lambert, who, like Jane Jacobs, was a dedicated preservationist.66

International Recognition

The international success of the La Cité project led to numerous invitations from abroad. For instance, Vecsei gave lectures in Beijing and Hong Kong to present housing solutions for Chinese megacities. Moreover, Yasmeen Lari, the Pakistani architect, invited Vecsei to collaborate on the development of downtown Karachi (1976) and a commercial centre (1978) Amid political tensions and governmental changes, interest in the project shifted, especially after Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s execution and the political involvement of Sariela, which steered events in a new direction.67

Another milestone in Vecsei’s international recognition68 came when she was invited to the “Les Femmes Exposent” (1978) exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. There, she exhibited alongside other pioneering women architects from around the world. She travelled to Paris with her husband, André, personally carrying the exhibition material, which was later displayed at the “Linear City” (1981) exhibition in Boston.

Eva Hollo Vecsei shared her expertise at several Canadian and American universities, including the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Calgary. In 1983, she received an architectural excellence award, and in 1988 and 1990, she was elected a member of the Canadian and American architectural associations. In 2004, she was honoured with the Ordre des Architectes du Québec’s commemorative medal.

From 1984, she continued working with her husband at their office, Vecsei Architects, where one of their important projects was the Marie de France College. The building excellently illustrates her architectural approach and philosophy: “If I get the program, I make something different from what was done before.”69 For the college’s design, she opted for a side corridor instead of the traditional central corridor, allowing morning sunlight to flood the classrooms. The school’s gymnasium roof was designed as a playground.

This practical approach was reflected in all her work. For her, functionality and practicality always came before aesthetics. She summarised her professional creed in one sentence: “Turning the mundane, a hut, into a palace.” She believed she thought “much more practically than men”. She saw problems as challenges, which led to new, unconventional solutions, such as her innovative approach to the placement of elevators and staircases in the Bonaventure building.

In the 1980s, Eva Hollo Vecsei visited Hungary for the first time after starting a new life in Canada. Despite her prominent career abroad, her work remained virtually70 unknown71 in Hungary, which is puzzling given that she was one of the most sought-after young talents of the 1950s. Today, her work is the only Hungarian-related material in the collection of one of the world’s leading architectural museums, the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Eva Hollo Vecsei is considered a pioneer of Canadian modernist architecture and is still highly respected in Canada, where she continues to live in Montréal.

Conclusion: Transnational Knowledge and Gendered Trajectories in Architecture;

The Career of Eva Hollo Vecsei

In examining the career of Eva Hollo Vecsei, the broader context of women’s professional trajectories in the 20th century becomes apparent, particularly within architecture. Her career provides insight into how migration and gender shaped architectural practice, especially in the transnational exchange of architectural knowledge. Vecsei’s solid grounding in large-scale urban design and concrete construction, developed in socialist Hungary in the 1950s, became an essential asset in her transition to Canada in the 1960s. This expertise, which included significant experience with large-scale projects, allowed her to integrate successfully into Montréal’s architectural environment, mainly through her work on projects such as La Cité and Place Bonaventure.

A central aspect of this study is Eva Hollo Vecsei’s rejection of being categorised under the label of “women’s architecture.” She resisted the idea of a gendered approach to architecture, emphasising her interest in complex, large-scale structures that required innovative solutions rather than adopting stereotypical feminine design approaches. This stance highlights the broader challenge of recognising women in architecture without reducing their contributions to gendered categories. For Eva Hollo Vecsei, architecture was not to be defined by gendered norms but by the complexity and scale of the structures she sought to create. However, her experiences also reveal how gender, as a structural condition, shaped her career. Gendered expectations and the professional challenges she faced were not just abstract concepts but practical barriers that affected her daily working life and opportunities.

Showing her trajectory is not only a “matter of adding a few names or even hundreds to the history of architecture [or] … a matter of human justice or historical accuracy, but of opening the field to its own productive complexity.”72 This approach underscores the need to rethink how architectural histories are framed beyond simply adding women to the existing narrative. While her refusal to be confined by gendered architecture is important, examining the structural conditions that shaped her experience as a woman in architecture is equally essential.

Based on this material in the context of the past, it is clear that gender differences in architecture were significant – a reality emphasised by Vecsei herself in interviews and autobiographical reflections. While the nature of these differences shifted over time, they remained palpable throughout the 20th century. Scholarship on gender and architecture has shown that “gendered architecture” – the association of certain design traits or professional roles with femininity – often served to marginalise women architects or to confine their work to a narrow set of acceptable specialisations.73 In both the United States and Canada, as well as in Britain, historians have documented how women in the profession were often steered toward areas considered an extension of domestic life: housing, interior design, and later, heritage conservation.74 These domains were legitimised as “feminine” spaces within the field, shaped by a belief in women’s supposed “natural” affinity and “supposedly innate understanding of things domestic”75: housing, interior design, and preservation (maintenance, care) rather than innovation or creation. As Gwendolyn Wright (1977) observed, these subfields became zones of professional legitimacy for women because they were seen as addressing the needs of other women, thereby reinforcing gendered expectations within architectural practice.76 In Canada, this division was socially enforced and institutionally reproduced through platforms like the RAIC Journal, which repeatedly emphasised such roles for women.77

Against this backdrop, Vecsei’s architectural practice stands out. Her work has not typically been framed in gendered terms nor associated with a “feminine” style. Instead, her role in large-scale developments such as Place Bonaventure and La Cité has been analysed primarily through the lenses of technical complexity, urban planning, and design efficiency. Where gender was referenced, it often positioned her as an outlier-a singular, “genius-like” figure who operated beyond the confines of the assumed professional sphere78, while at other times, her architecture was even described as “masculine.”79 Her public remarks echo this positioning, reflecting a conscious effort to distance herself from stereotypes surrounding women’s design sensibilities, as she insisted that she should not be put “in the category of women who add their little pink touches.”80

On the other hand, the structural conditions of being a woman in the architectural profession in this period were far more pervasive – a common experience for women hailing from Eastern Europe and integrating into Canada, the Québec pioneers. These conditions have been examined in terms of working environments (a male-dominated culture), professional status (Vecsei faced more significant difficulties integrating into Canada compared to her husband), available positions (she initially worked on a probationary basis), personal experiences (such as using Librium to cope with professional pressures), and societal perceptions (concerns about whether a woman with children could work, both in the Netherlands and Canada).

In conclusion, Eva Hollo Vecsei’s career highlights the complex relationship between migration and gender in architectural history. Her emigration to Québec in 1957 not only provided opportunities to apply and further develop her architectural expertise, formed in socialist Hungary, but also exposed the significant challenges she faced as a female architect with a migration background in a male-dominated profession. Her career trajectory illustrates the difficulty of navigating between her extensive architectural knowledge and the cultural and gendered obstacles she faced in a new professional environment. Nevertheless, through her openness to innovative building methods, resilience, and refusal to conform to gendered expectations, she found her footing in Montréal’s architectural scene after an uncertain beginning. Her background and large-scale design expertise, as well as her contributions, were not only appreciated but also seen as key to shaping Montréal’s architectural landscape and the evolving professional presence of women in Canadian architecture.

This paper was prepared within the framework of the research program titled “Hungarian Women Architects,” organised by the Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Center (MÉM MDK) and supported by the National Cultural Fund (NKA) of Hungary.

The author acknowledges the support for the publication costs by the Open Access Publication Fund of Bauhaus Universität Weimar and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). The author hereby expresses gratitude to Eva Hollo Vecsei and her daughter, Andrea Vecsei, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture for providing access to the archive and facilitating personal and online meetings. Special thanks are also extended to Dániel Kovács for initiating the program.

Enikő Charlotte Zöller

orcid: 0009-0001-9491-8060

DFG Research Training Group “Gewohnter Wandel”

Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism

Bauhaus University Weimar

Belvederer Allee 9

D-99425 Weimar

Germany

Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Center

Vigadó tér 2

1051 Budapest

Hungary

enikoe.charlotte.zoeller@uni-weimar.de

Born as Éva Holló, she married András Vecsei in 1952 in Budapest. In Canada, she is referred to as Eva Vecsei. In this text, I refer to her as “Eva Hollo Vecsei,” aligning with the naming convention used by the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). Her Hungarian name is the following: Vecsei Holló Éva. András Vecsei is referred to as “André Vecsei,” which also aligns with the CCA’s naming convention. When mentioning “Vecsei” in this text, I am referring to Eva Hollo Vecsei, not her husband.

Magyar Építőművészet, 1952, 1(4), p. 266.

ADAMS, Annmarie and TANCRED, Peta. 2000. Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p. 65.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Email to Enikő Zöller, 3 December. Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat, saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews during World War II by issuing protective documents and establishing safe houses. Captured by Soviet forces in 1945, his fate remains unresolved. He was posthumously honoured as “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem. YAD VASHEM. 2025. Raoul Wallenberg [online]. Available at: https://www.yadvashem.org/righteous/stories/wallenberg.html (Accessed: 25 April 2025).

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Email to Enikő Zöller, 3 December.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

The Max Reinhardt Seminar is named after Max Reinhardt, the world-renowned Austrian director who founded the school in 1928 to train new talents for the theatre. The institution is still operational today and is located in Vienna.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

For a very comprehensive overview of the role of the Technical University in providing a solid foundation for emigrants in 1956 and the institutional setting, see: KARÁCSONY, Rita and VUKOSZÁVLYEV, Zorán. 2019. Emigration of Architects and the Foundations of Modernism: Hungarian Architecture Students Entering the Profession Abroad After the 1950s. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 53(3–4), pp. 182–195.

Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev, Z., 2019, p. 184.

ISTVÁNFI, Gyula. 2015. Adatok a magyar építészképzés műegyetemi történetéhez 1945 – 1990. Rendszerváltástól rendszerváltásig. Építés – Építészettudomány, 43(1–2), p. 5.

Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev, Z., 2019, pp. 185–186.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev, Z., 2019, pp. 185–186.

Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev, Z., 2019, pp. 185–186.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev, Z., 2019, p. 186.

For an overview of the historical representation of women in formal education in technical disciplines in Hungary: PALASIK, Mária. 2003. A magyar nők a műszaki felsőoktatásban, a mérnöki pályán és a műszaki tudományokban a XX. Században. Múltunk, 3, pp. 132–159. For a more specific focus on architecture: BÖRÖNDY, Júlia. 2025. “A körülmények szembeszökő változása” – Így alakult át a nemek aránya a hazai építészképzésben. Építészfórum [online]. Available at: https://epiteszforum.hu/a-korulmenyek-szembeszoko-valtozasa–igy-alakult-at-a-nemek-aranya-a-hazai-epiteszkepzesben (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

Estimation by Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev Z., 2019, p. 194.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

Karácsony, R. and Vukoszávlyev, Z., 2019, p. 185.

The whole paragraph is based on: Interview with Eva Hollo Vecsei. 2023. Conducted by KOVÁCS, Dániel and ZÖLLER Enikő. Online, 28 November.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 64.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 64.

VECSEI, Eva. 1993. Projets et pratiques de femmes architectes. In: Tardy, É., Descarries, F., Archambault, L., Kurtzman, L. and Piché, L. (eds.). Les Bâtisseuses de la Cité, Association canadienne-française pour l’avancement des sciences. Montréal: L’Association, p. 203.

According to Eva Hollo Vecsei, one of ARCOP’s unique aspects was the diversity of its members: Affleck, Desbarats, Dimakopoulos, Lebensold, and Sise all came from different cultural backgrounds, reflecting the multicultural nature of Canadian society. Affleck represented English Canada, Desbarats French Canada, and Lebensold the Jewish community. HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

In 1965, five of Québec’s eighteen female architects worked at ARCOP. Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 61.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 61.

Eugenio Giacomo Faludi, originally named Faludi Jenő, was a Hungarian-born architect who worked in Italy, then later moved to London and emigrated to Canada in 1940.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 70.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 64.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 64.

In Canada, specifically in British Columbia, 77% of female architects prior to 1970 were immigrants. RICHTER GREER, Nora. 1982. Women in Architecture: A Progress (?) Report and a Statistical Profile. AIA Journal, 71(1), p. 47.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 74.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 65.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 64.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 60.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 63

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 62.

Montréal Star 1965 cited in Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 62.

Comment made by her daughter Andrea Vecsei. HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2024. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Ágnes Anna Sebestyén, Montréal, 16 June.

VILORIA, James. 2013. Eva Vecsei. The Canadian Encyclopedia [online]. Available at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/eva-vecsei (Accessed: 12 April 2013).

SCHMERTZ, Mildred and MOLITOR, Joseph W. 1965. Place Bonaventure. Architectural Record, special report, July, p. 125.

BANHAM, Reyner. 1976. Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past. London: Thames and Hudson, p. 120.

Schmertz, M. and Molitor, J. W., 1965, p. 125.

Karácsony, R., 2017, p. 289.

Vecsei, E., 1993, pp. 203–204.

Vecsei, E., 1993, pp. 203–204.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 65.

SCHMERTZ, Mildred. 1987. Vecsei, Eva. In: Morgan, A. L. and Naylor, C. (eds.). Contemporary Architects. Chicago: St. James Press, p. 946.

American Institute of Architects Journal. 1990. International Architects Named Honorary Fellows. American Institute of Architects Journal, May, p. 43.

Banham, R., 1976, pp. 120–125; Viloria, J., 1994; Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 61.

SCHMERTZ, Mildred. 1978. La Cité. Architectural Record, 1, pp. 111–116.

Schmertz, M., 1978, p. 114.

CANADIAN CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURE. 2025. Eva Hollo Vecsei collection [online]. Available at: https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/archives/491691/eva-hollo-vecsei-collection (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

BOYER-MERCIER, Pierre. 1988. Pratiques et pratiquants: Eva Vecsei et André Vecsei. ARQ, 42, pp. 20–24; CRAMER, James P. (ed.). 2003. Leading Women Architects and Designers of the 20th Century. In: Cramer, J. P. and Evans Yankopolus, J. (eds.). Almanac of Architecture and Design 2003. 4th edn. Atlanta, GA: Greenway Group, p. 414.

HOLLO VECSEI, Eva. 2023. Interview by Dániel Kovács and Enikő Zöller [online], 28 November.

The most detailed study to date on Hungarian architects who emigrated following the 1956 revolution is Rita Karácsony’s research, titled “The Life and Work of Architects Forced Abroad in ’56 – Data from a One-Year Long Architectural Historical Investigation.” In this paper, Karácsony devotes an entire page to Eva Hollo Vecsei, providing a concise yet notable overview of her trajectory. Karácsony, R., 2017, pp. 276–294.

“There are many whose work we know almost nothing about, even though, for example, the Vecsei couple’s contributions left a mark on the image of Montréal. Those who are better known are those who return home and have already presented their work here.” HANTHY. 1995. Építészmonográfiák. Vidolovits László utolsó kívánsága. Magyar Nemzet, 9 January, p. 14.

COLOMINA, Beatriz. 2018. “The Secret Life of Modern Architecture or We Don’t Need Another Hero”, presentation at Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 28 March 2018 [online]. Available at: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/event/beatriz-colomina-the-secret-life-of-modern-architecture-or-we-dont-need-another-hero/ (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

STRATIGAKOS, Despina. 2016. Where Are the Women Architects? Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 5–20; Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, pp. 4–12.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 60.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 60.

WRIGHT, Gwendolyn. 1977. On the Fringe of the Profession: Women in American Architecture. In: Kostof, S. (ed.). The Architect: Chapters in the History of the Profession. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 280–308.

Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 60.

Eva Vecsei was the only Canadian woman, among eleven Canadian men, featured in Contemporary Architects (1980), and remained listed in the 1987 edition. Editor Mildred Schmertz noted that the Place Bonaventure project showcased “her own geometric and spatial skills, her knowledge of architectural form and theory, and the power to coordinate, integrate and synthesize the knowledge of others.” Schmertz, M., 1987, p. 946.

Vecsei, E., 1993, pp. 203–204

Montréal Star 1965 cited in Adams, A. and Tancred, P., 2000, p. 62.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.4

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License