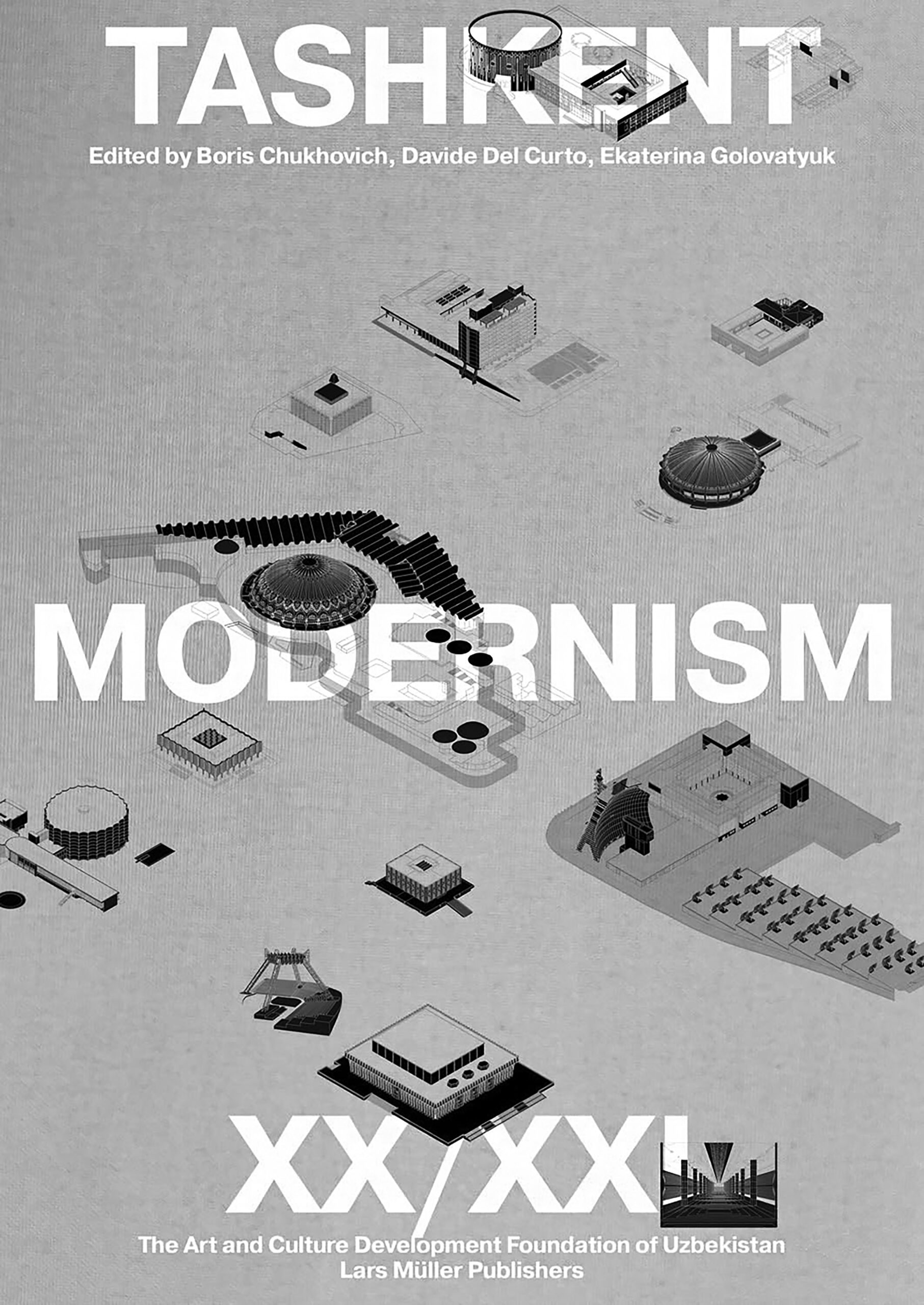

Tashkent Modernism

XX/XXI, 2025

Chukhovich, Boris, Del Curto,

Davide and Golovatyuk,

Ekaterina (eds.)

Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers

ISBN 978-3-03778-751-9

Though it might seem counterintuitive at first, a catastrophe can be a true catalyst for progress. As the violent earthquake on 26 April 1966, created space for the truly unique legacy of Tashkent postwar modernism, the violence of the recent demolition of the well-known modernist landmark, the Palace of Cinema (Rafael Khairutdinov, 1982), itself launched the extensive Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI project, backed by the Arts and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) of the Uzbek Ministry of Culture (p. 11). One of the tangible results of this stunning,

multilayered research effort is the seminal publication Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI; even more significantly, it led to the legal protection of two postwar structures already intended for redevelopment and the initiation of heritage protection for several others. Perhaps the highest form of achievement a researcher or architectural historian can hope for – besides deepening the body of knowledge – is the direct influence of their efforts in the real world, and here the Tashkent Modernism project is an inspiring example. Yet while the project’s impact is undeniable, its scope and methods also reveal the complexities and contradictions inherent in preserving themodernist legacy.

Given the threat to the Uzbek capital’s heritage of the recent architectural past from large-scale transformation, the project seeks to preserve it through value mapping and re-contextualizing both locally and globally. Working with Politecnico di Milano, the ACDF developed a management plan presenting the potential to revitalize and integrate the cultural heritage of the recent past into the future. The legacy of modernism in Tashkent, once the Soviet Union’s fourth-largest city, presents a unique synthesis of architectural influences: simple functionalist geometric lines, the incorporation of traditional Uzbek ornaments and design elements, and progressive structural engineering designed to mitigate seismic activity, all embedded in a new vision of a spacious urban environment that replaced the ruins after the earthquake. All of these aspects are covered in the publication, which is divided into two parts.

Part One is a collection of visual and written essays, starting with a conversation between Rem Koolhaas and Ekaterina Golovatyuk on modernity and preservation. Koolhaas, whose Cronocaos exhibition and influential lecture Preservation Is Overtaking Us significantly shaped global debates on the preservation of modern architecture, offers a fitting entry point into the publication’s broader themes.1 The research essays are further subdivided into two parts – the first as a recontextualization of Tashkent’s architecture before, during, and after the earthquake, as well as examining the typology and local specifics of Tashkent modernism; the secondfocusing on the preservation of modernism, including the methodology, legislation, and specifics of preserving Tashkent’s recent heritage. A visual essay follows.

Part Two consists of twelve “monographs” each devoted to a single building, effectively operating both as an “archive” and as a heritage assessment plan. Each monograph presents the results of historiographic research, archival documents, architectural concepts, and current

conditions, mapping architectural and cultural value, and finally assigning specific levels of interest to various parts of the building, as well as prescribing allowedinterventions, future uses, and required conservation activities. A preservation graph positions each selected project based on two parameters – use (new or old) and level of intervention (conservation or preservation) – and concludes that the optimal approach to most of the structures is more of a traditional one: to conserve them and keep the original function. This rather conservative approach also comes as a surprise, given the more flexible approach to integrating these structures into current urban life presented in several of the preface papers.

While the structure of the publication is impressively comprehensive, some of its key methodological claims invite closer scrutiny. The instrumental element behind the efforts to protect the strongly contested architectural heritage of the recent past is precisely the objective methodology of value mapping — in layman’s terms, identifying which crucial values a structure represents, and which ones might be sacrificed in the name of progress. Such concessions allow for retaining the structure while adapting it to new uses or upgrading the technical side of things, for instance, to make its thermal performance more sustainable for the municipality. However, this crucial point feels underdelivered when compared to the ambitions of the project. The several introductory texts bring focus to the twelve projects, the “monographs”, and the value mapping, their specific protected elements, and the space for reinvention. And of course, a robust scientific basis for value mapping is crucial in debates with private developers or the public when communicating the need for preservation. However, in Methodology for Preserving the Modernist Architecture of Tashkent by Davide Del Crudo, such general phrases such as “contemporary conservation therefore aims to preserve the inherent polysemy of every fragment of the past, to enable everyone to decipher possible meaning or values” (p. 168) remain largely conceptual. As such, the conservation management plan consequently consists of brief texts summarizing architectural values. And, while the introduction by Boris Chukhovich, Davide Del Crudo, and Ekaterina Golovatyuk suggests that a varied level of intervention and adaptation will be presented (p. 29), most of the existing substance of the twelve projects featured as part of the monographs is, however, classified as “Level 1 – Maximum level of interest, no transformation allowed,

conservation activities required”, or some of the substance as “Level 2 – Medium level of interest – elements included in this level can be moderately transformed pending approval by a designated preservation committee”. It is entirely plausible that the structures featured in the publication were carefully selected as truly valuable representations of postwar Tashkent architecture and that indeed almost everything within these twelve structures is invaluable. However, a more nuanced reading of these buildings might still reveal that certain elements are less critical than others, allowing for a more differentiated and subtle approach.

This discrepancy between the project’s conceptual framing and its execution reveals two limitations. First is the lack of typological diversity: if nearly every selected structure is treated as equally sacrosanct, it becomes difficult to articulate which qualities truly distinguish the most exceptional examples within the broader post-war stock – and why. Second is the limited methodological applicability: the publication demonstrates how to safeguard iconic structures but not how to prioritize or negotiate change within the many more numerous and ambiguous modernist buildings that inevitably face evolving demands for their program and sustainability. Considering that postwar modernism was a global movement and the pressures threatening it are similarly global, a demonstrated capacity for international transferability would significantly enhance the publication’s scientific and practical impact.

The focus of the publication on the twelve most iconic postwar structures of Tashkent and the ways they could be conserved is, however, understandable given that the catalyst for the effort was the ruthless demolition of a beloved postwar civic structure in Uzbekistan’s capital. In this sense, the project’s initial emphasis on safeguarding the most emblematic examples serves both a symbolic and a practical purpose: to assert the legitimacy of modernist heritage in a context where its value had long been doubted. By setting a clear precedent, the project

lays the groundwork for a broader and more nuanced preservation strategy in the future.

Tashkent Modernism is a commendable, complex, and inspiring effort that reminds us, in Slovakia and Central Europe generally, that our position is anything but unique confronted with the aging heritage of postwar public structures, often of extraordinary architectural quality yet threatened by insensitive development. It reminds us not only of their potential but also of the tangible impact that scientific research, when applied with conviction, can have in shaping public awareness, policy, and preservation practice.

This paper was partially supported by the VEGA agency

(Grant no. 1/0063/24), and the Early Stage Grant scheme of

the Slovak University of Technology (Grant no. 23-05-04-A).

KOOLHAAS, Rem. 2012. Preservation Is Overtaking Us. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License