In 1879, the Hungarian city of Szeged was destroyed by the flooding Tisza River, necessitating its rebuilding from Lajos Lechner’s plans. With it, Szeged developed a central urban structure, with a circular embankment aligned with the boulevards protecting it from floods (Szegedi Körtöltés). In the 1930s, Dr. Endre Pálfy-Budinszky, Szeged’s chief architect, began developing a modern green space system plan, focusing on the Tisza and its green belt, the circular embankment, and the green space along the embankment. To ensure that the embankment would function as a green belt rather than a border, he also considered the city’s other green spaces and planned green strips between the boulevards. He also adopted Gestalt psychology in designing a green space network starting with the circular embankment’s characteristics. This study introduces measures for green spaces in the 1930s, their cultural and intellectual background, and their European context based on historical sources and archival documents.

Introduction

This study examines the history of Szeged’s green ring, focusing on the work of Dr. Endre Pálfy-Budinszky.1 It outlines the international and domestic paradigm shifts in intellectual history and urban architecture, especially in the 1930s when the Szeged ring embankment was defined as an urban green belt instead of a physical and mental border. This study further discusses the literature advocating the current need for urban architecture to incorporate nature.

The Development and History of the Circular Embankment

First, I will discuss the history of Szeged’s circular-route urban structure, and specifically the development of the circular embankment within it.2

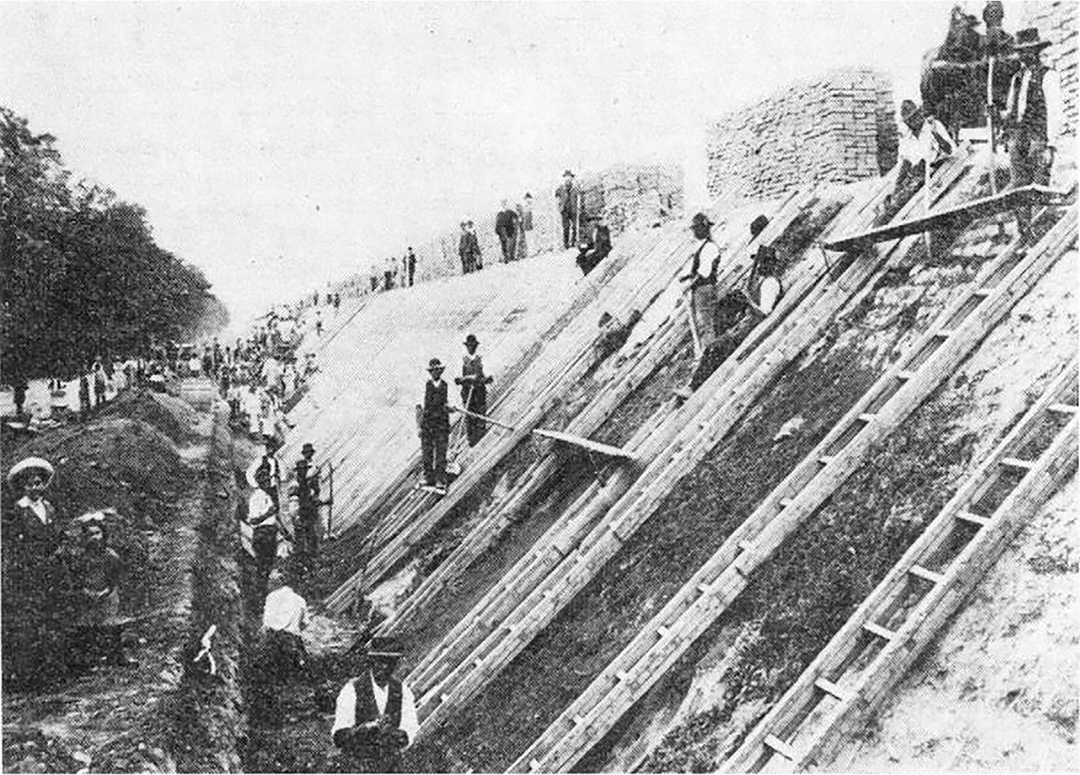

In the southern part of the Hungarian Great Plain, high elevations – such as the circular embankment which has surrounded the city for almost 150 years – are not common. Szeged’s circle embankment is, in fact, a secondary line of flood defense necessitated by the great flood of 1879, which destroyed most of the city and left only 300 of its nearly 6,000 buildings intact.3 The city’s reconstruction included the creation of a network of circular and radial streets, the outer edge of which is the circular embankment.4 Lajos Lechner,5 the architect of the reconstruction, took into consideration all the requirements of a modern city: the development of transport, the accessibility of workplaces, and the need for air and sunlight. He designed wide streets, boulevards, parks, and promenades inspired by the radiating structure of Paris.6

In Szeged’s central urban structure, the circular embankment is the fourth circular road protecting the city against flooding, enclosing 17 kilometers of the city, with the road abutments also functioning as dikes.7 After World War I, expansion began outside the circular embankment with the establishment of settlements encircling Szeged: new suburbs bringing together people of different identities and social classes.8

The Role of Green Spaces in Urbanism and Cultural History in the 1930s

Around 1930, the circular embankment’s urbanistic potential was highlighted as a well-utilized urban green space. Previously regarded as a social, mental, and physical boundary, the embankment emerged in this decade as an advantageous natural form, a landscape worthy of inclusion in urban development and enhancement.9 In the following sections, I will chronologically discuss the complex process underlying this development.

The first and most important turning point was the modernization of urban and social architecture inspired by Le Corbusier and the creation of the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1929. Its membership included all the prominent architects of the time, many of whom were Hungarian, including Farkas Molnár and Máté Major, who published their own journal (Tér és forma – Space and Form) and presented their modern architectural endeavors in many exhibitions. They campaigned against Hungary’s underdeveloped housing construction and promoted social architecture.10 Among their most crucial efforts ranked the definition of the various uses of urban space, including the ideal proportion of green spaces.11

Their activities led to the founding of the Hungarian Engineers and Architects Association’s Urban Planning Committee in 1929, the Budapest Urban Planning Committee, and the Szeged Committee in the same year. Virgil Bierbauer wrote about the urban planning problems of Budapest,12 Domokos Berzenczey on the urban planning issues surrounding Hungarian rural towns,13 and Pálfy-Budinszky on the need for urban planning in Szeged.14

The Career of Endre Pálfy-Budinszky and Presentation of the Impact

Pálfy-Budinszky’s writings in Space and Form and the printed booklets summarizing his lectures are crucial milestones in the growing Hungarian urban planning literature that I consider particularly important, in large part because his life’s work and the source material documenting it have disappeared almost without trace. The first half of the 1960s saw a collaboration between Pálfy-Budinszky and his colleague and friend Sándor Bálint,15 an ethnographer from Szeged, on a study on the history of the city center (the manuscript is now in the Sándor Bálint archive, which is kept by the Ferenc Móra Museum in Szeged).16 In 1965, Sándor Bálint was sentenced to prison for possession of books critical of the regime, while Pálfy-Budinszky was accused of placing these illegal books in his possession before the search. As a result, Pálfy-Budinszky was dismissed from his post as chief engineer, libeled as a political criminal, and saw his work banned from further publication.17

A descendant of the Pálfy family of Szeged, Pálfy-Budinszky graduated as an engineer from the Technical University of Budapest in 1926, after which he worked for the Szeged Flood Control and Water Control Association, forming his commitment to the Tisza River for the rest of his life. He began to publish his own writings in the 1930s, when he prepared urban development plans, revitalized urban literature, and became the driving force behind Szeged’s urban development and monument protection. In 1931, he participated in the International Congress and Exhibition on Housing and Urban Planning in Berlin and presented papers and participated in the CIRPAC Congress in Paris in the same year. After 1930, he published articles on social housing,18 and on open spaces and urban vegetation starting in 1933.19 In 1934, he translated Pál Ligeti’s paper on new architecture into German20 and, from 1935, wrote about the role of cycle paths in urban development as well as the integration of the Szeged embankment and the surrounding former industrial areas into a green belt.21

In 1937, he helped create the law on building and urban planning, drawing on his French and German study trips. In 1938, he became the chief of the town planning department.

A turning point in Pálfy-Budinszky’s approach was the Athens Charter during the 1933 CIAM Congress, which became the basis of urban planning theory and practice for a long time. Another influence was the discipline of Gestalt psychology emerging at the time; among the followers of the school of Gestalt psychology, Kurt Lewin and his concept of field theory had a major impact on architectural and spatial planning. This concept was based on the idea that the individual and their surrounding environment (= field) are constantly interacting with each other and that the development of the human personality is not shaped by purely internal, psychological factors but by active interaction with the environment.22 Similar ideas had been outlined by Heinrich Wölfflin at the end of the nineteenth century, when he sought to interpret architecture on a purely psychological basis in his work Zu einer Psychologie der Architektur.23 It was at the International Congress on Housing and Urban Planning in Berlin that Pálfy-Budinszky encountered the new theoretical background to German efforts and was greatly influenced by Otto Bünz24 and Otto Blum25 (Berlin’s contemporary urban planners).

The extensive urban growth resulting from the Industrial Revolution eclipsed the city’s welfare function in favor of industry and production, and at the turn of the century, the garden city movement**key=26** emerged as an alternative to increasingly uninhabitable cities. Its advocates expressed the urban public’s need for green spaces, and the urban architecture schools that emerged in the twentieth century from the outset consciously advocated using green spaces in urban planning. Since in the 1930s, several Budapest engineers (Dezső Molnár,27 Virgil Birbauer,28 Dezső Morbitzer29) were discussing the neurodestructive effects of a city that lacks green spaces and the need for larger urban green spaces, urban planning also used the findings of other disciplines to find effective solutions. Psychologist Pál Ranschburg published an article in Urban Review on the psychological importance of urban noise abatement and techniques for doing so, including the introduction of noise insulation practices,30 while Dezső Morbitzer, Budapest’s chief gardener, drew upon botanical research to design psychologically positive urban spaces.31

The Meaning of “Open Spaces, Green Spaces” in the Work of Endre Pálfy-Budinszky

In Szeged, these Hungarian and international theories found a synthesis in Pálfy-Budinszky’s work, providing inspiration for the first modern housing estate construction projects and the incorporation of psychological research results into design. His goal was the same as that of Le Corbusier: to make Szeged’s apartments healthy, bright, and well-ventilated and to provide enough green space for sports and recreation in the building’s urban environment. Pálfy-Budinszky was also the first to develop a cycle path network in Szeged, in the belief that a person who is active outdoors is honest and healthy-minded and that a green urban environment can transform the habitus of the people living in it. For the same reason, he became increasingly concerned about the green utilization of the circular embankment, continually publishing from 1937 onward articles on related possibilities, the first of which was titled “Open Spaces, Green Spaces” (1937).32

In his words: “Open spaces are important from three points of view, namely aesthetics, hygiene and psychology. Although the aesthetic aspect has played a role mainly in the past, it is not unimportant today for constructive and practical aesthetics. But more important than these effects is the psychological one: the effect of water and greenery as a means of sympathy on our moods. Both delight and soothe our eyes and nerves. And the honesty and healthy thinking of people who spend a lot of time outdoors is well-known.”33

In his doctoral thesis entitled “The Changing Role of Open Spaces in Major European Urban Renewal”, Péter Balogh points out that the first definition of “open space” to appear in Hungarian was that of Endre Pálfy-Budinszky.34 In his research, he highlights that the concept of free space appeared in Hungary before the Second World War, under the influence of the German “Freiraum”, though directly following Pálfy, who understood the term to mean an area where there are green space and water, and where there is no dust, noise, and traffic.35 “In addition to their aesthetic value, open spaces have an invaluable psychological and health value,” writes Pálfy in a later study.36 “It is a professional and forward-looking definition from today’s point of view, and if it had stuck in the vernacular at the time, it would have been able to evolve with changing circumstances. It has not stuck because it has been replaced by ‘free area’ (written separately),” the latter term, devoid of the other’s lyricism, merely refers to uninhabited territory and eventually fades from the vocabulary. According to Balogh, Pálfy’s concept of using the interior space of blocks of land for landscaping to make the city greener can be interpreted as a foretaste of the block rehabilitation of Budapest that unfolded in the 1960s.37

The Process of Creating Green Spaces in the Work of Endre Pálfy-Budinszky

Primary in the development of Pálfy’s attitude towards the design of green spaces was his continuous self-education: between 1928 and 1964, he visited every Hungarian town at least once, whether individually or organized by the National Association of Urban Engineers, and studied its building conditions. He incorporated this knowledge into his urban development plans for Szeged and, thanks to his erudition and knowledge, managed to create spatial planning concepts significantly ahead of their time.

The development of his outlook was largely influenced by the international congresses (Berlin, Paris) where he participated as a contributor as well as auditor. As a result, he began to attach increasing importance to the beneficial effects of urban green space on the human soul and character, and systematically develop his green belt programme.

Eventually, Pálfy-Budinszky published his wide-ranging treatise on the role of open and green spaces in urban planning, first presented at an urban planning survey meeting in Szeged, in four parts in the journal Városkultúra [Urban Culture] in 1933.38 Here, Pálfy clarified in detail his definition of open space, which was ahead of its time in its thorough and sensitive definition. By open space, he does not mean undeveloped parts of the city, but rather zones which can be used as potential green spaces and offer recreational opportunities, such as: “1. green areas kept entirely free from development and traffic, i.e. forests, fields and parks; 2. water areas, provided that they are not excessively used for water transport, in particular for steam-powered navigation; playing fields and sports grounds, although the latter tend to produce dust and are rarely available to the public; 4. cemeteries; 5. large private gardens, provided that they are directly connected to public parks or are partly available to the public; 6. larger settlements with a relatively small number of buildings in a large green area, such as hospitals, schools, possibly barracks with training areas, etc.; 7. garden centres, allotments, nurseries.”39

In summary, green space implies the presence of vegetation and water; yet it does not, for example, include a landscaped inner-city street. Pálfy’s innovation, at least in the Hungarian context, is that his writing takes into account not only the physical but also the psychological effects of open spaces, while at the same time demonstrating his social sensitivity. Instead of the traditional chateau parks, only accessible to insiders, he thinks in terms of public gardens open for the masses, where the landscape design itself is fitted to the needs of the ordinary person. The sophisticated plantings of a chateau park are understood only by the educated aristocracy, whereas a people’s garden should be conceived to meet the needs of the working masses. “The masses are not looking for the most sensitive flora; they want forests and meadows. The people don’t want to keep themselves to winding paths, but want to move freely, to sit on the grass. It is, therefore, not right to introduce too much detail into the people’s garden”, he writes.40

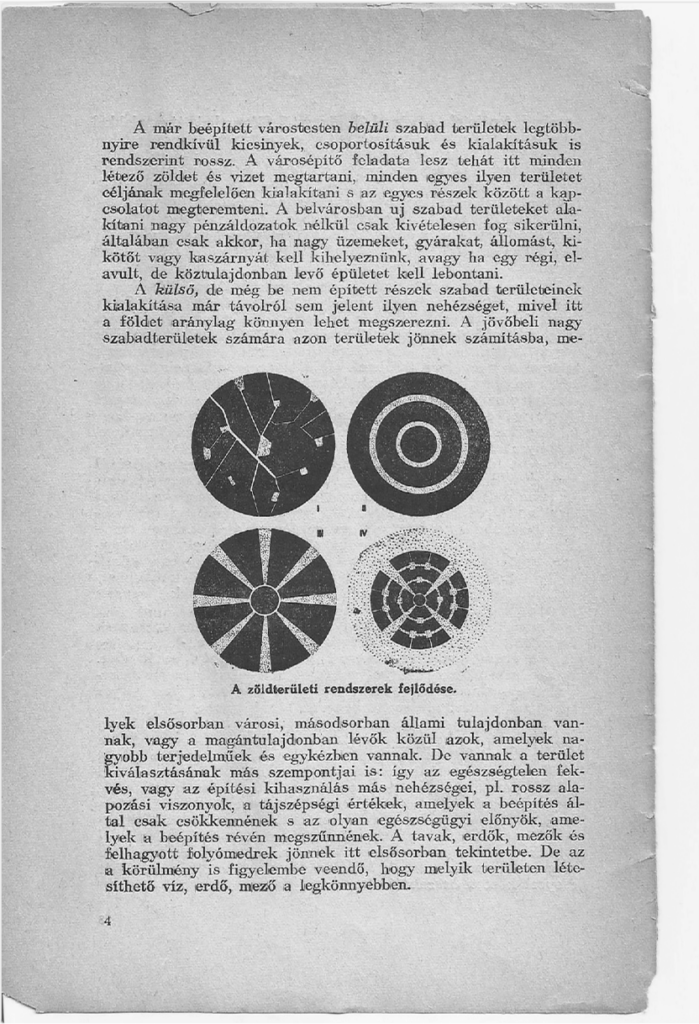

It was in this paper that he first formulated the two basic principles that would later shape his design work: the embedding of the city in a vast sea of green space and the interweaving of the urban body with green veins as a form of modern open space.41 In line with contemporary German urban planning principles, Pálfy envisaged 30 m2 of green space per inhabitant. Particularly in the flat lowlands, where natural beauty is scarce, every resource must be exploited to meet this ratio, hence the connection between flat land and water, i.e. the floodplain as open space, becomes a key element for him.42

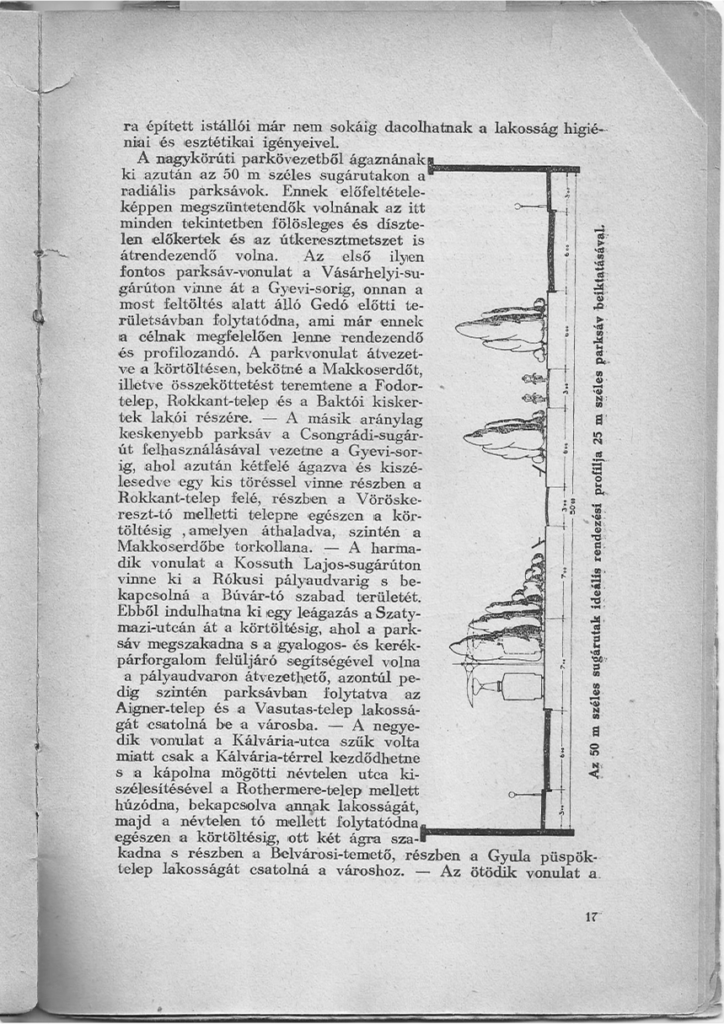

In terms of open spaces, he deals with cycle paths first, even before urban parking or car lanes, a tendency that can be traced back to his major 1937 study. The bicycle path system is treated as important because of the increased bicycle traffic arising fro the development of Szeged as a suburban settlement. Pálfy envisaged a network of interconnected cycle paths in a wide parkway network, with a four-metre parallel parkway strip separating the car from the cycle path. Truly a state-of-the-art solution for urban green spaces of its time, this park-lane design unfortunately has never been implemented.43

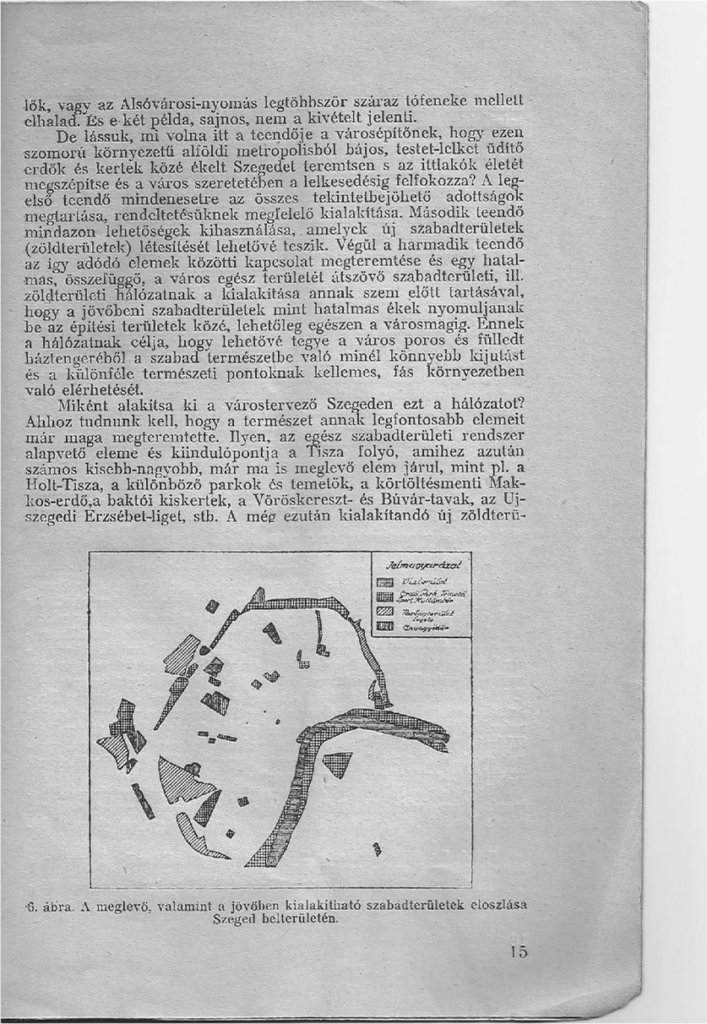

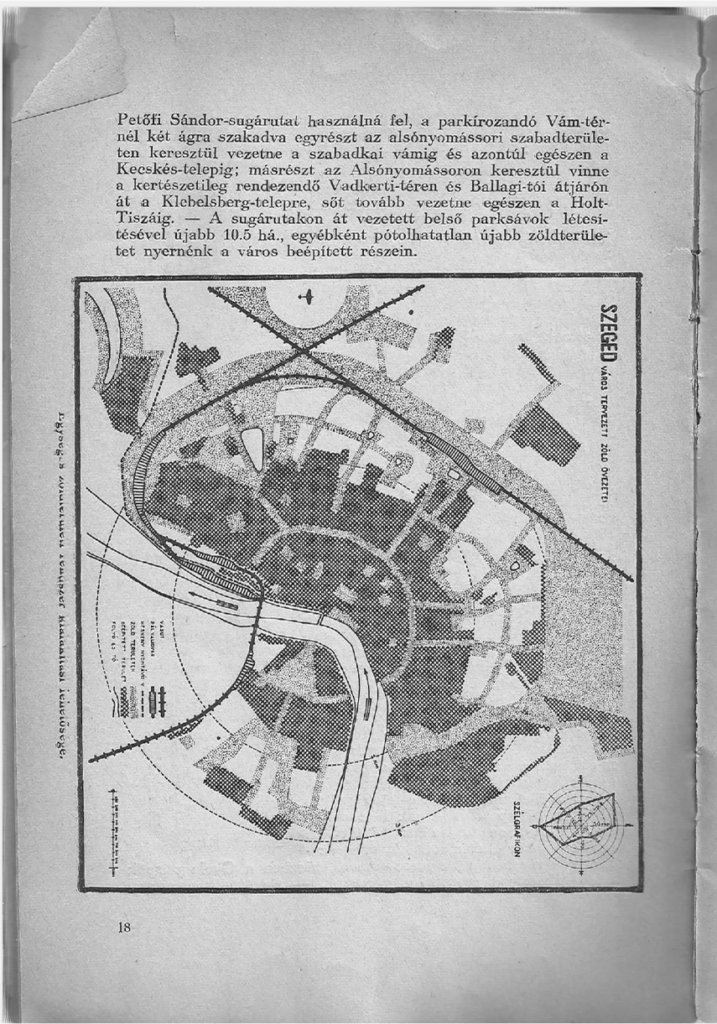

In 1939, in “Open Spaces and Green Spaces”, we find an already complete city-wide green-space programme laid out.44 The concept of a green boulevard in the city, likewise left unrealised, is outlined as follows: alongside boulevards 50 min width, 20–25 m wide park strips would line the roads on either side, connecting the various city districts. He envisaged five such park-lane boulevards in Szeged, which would have meant a total of 140 hectares of additional green space, aiming to gain more green space by internal park-lane passing through the boulevards.

“The circular embankment, as a defining feature of Szeged, would be integrated into the new park network as a panoramic walkway: at its inner plinth, a circular stitching of about 50 m wide shaded park-lane would be created at the inner foothills.”45 On the edge of the built-up area of the city, a park strip would be created between each of the radial park lines, enclosing the whole city. In those parts of Szeged where the parkway would not be wide enough, building restrictions would be imposed to make it possible. Additionally, the plan mapped green areas outside the city limits that would be kept free from development, such as water areas within the ring fills, disused clay mines, and floodplains. The future development of a unified park system, he believed, was important for the health of its population, and therefore much of the virtue of open space is also linked to healthy living.

Health, moreover, was itself promoted through urban design: through situating sports fields in several parts of the city, accessible via park tracks, the very process of reaching them is part of the exercise. Additionally, sports parks, sports stadiums, golf courses, motor racing tracks, ski and toboggan runs – a feature entirely absent from the towns of Great Hungarian Plain – playgrounds, and in every quarter of the town, groves of woodland, with cleared, woodland-like planting. Or further, boating lakes, paddling-pools for children. Pálfy is already talking here about “a correct and purposeful park policy”,46 drawing upon all the results of his research to date.

In 1940, he described the planned development of green spaces around the town and the natural assets to be protected (Fehér-tó [White Lake], Holt-Maros [Dead Maros], etc.).47 Subsequently, in 1941 he elaborated the urban development plan of Szeged on behalf of the Ministry of Industry, the City Council and later the National Planning Office.

The sub-chapter entitled “Natural Beauties” reveals that Pálfy subordinated architectural thought and intervention to nature: “The characteristics of the landscape impose obligations on urban planning in several respects: the most characteristic parts of the land surface, the elevations, depressions and water spots should be preserved as naturally as possible. Roads should blend in, and buildings should adapt to the surrounding landscape.”48

Unfortunately, Szeged has few such natural assets, and therefore Pálfy takes special care to examine and make use of them. He is the first to draw attention to the valley-like course of the Holt Maros, an oxbow of the Maros River, where magnificent walking paths could be built and in fact were realized. Abandoned brickworks, clay pits used as rubbish dumps, bushland, and waterholes are proposed for transformation into natural beauty spots and hiking trails. In turn, the areas of forest outside the city could be made into hiking destinations by adapting public transport and bus services. And he was the first to draw attention to the value of the White Lake (now a nature reserve): “This area, unknown to most people in Szeged, has been reported in foreign magazines, and ornithologists from distant countries have come to Hungary to visit it and study its rare fauna. It is in the national interest to fence it off as soon as possible.”49

The circular embankment, as described in detail later in my study, is not presented in this consideration in terms of a green ring for motorized transport, but as a pedestrian walkway “from which the cityscape presents the most varied face of Szeged when viewed from all around.”50

Between 1947 and 1949, under a commission from the Ministry of Construction and Public Works, he prepared the zoning plan of Szeged’s farm centres and the neighbouring villages, in 1947 the programme for the transformation of the industrial districts between the railway lines on the banks of the Tisza, and in 1948 the zoning plan of the industrial district on the right bank of the Tisza. In 1961, Pálfy was the only non-metropolitan member of the preparation committee for the National Building Code, largely due to his ability to ensure implementation of his programmes, except for the grandiose green planning plan. Today, it would be worth rethinking Pálfy’s former plans, because according to a 2015 figure, instead of the 30 m2/year of green space he envisaged, we currently “boast” only 23 m2/year of green space.51

A Real-Life Example: the Ring Earthwork as Circular Embankment

In “Open Spaces,” Pálfy-Budinszky outlines the concept of an ideal circular embankment forming a scenic walkway integrated into the urban park network, containing playgrounds, rest areas every 500 meters, and bicycle paths. On the embankment’s inner side, it was designed as a 50-meter-wide shaded parkway along its entire length, forming a system of open spaces connected to scattered parkways throughout the city.52

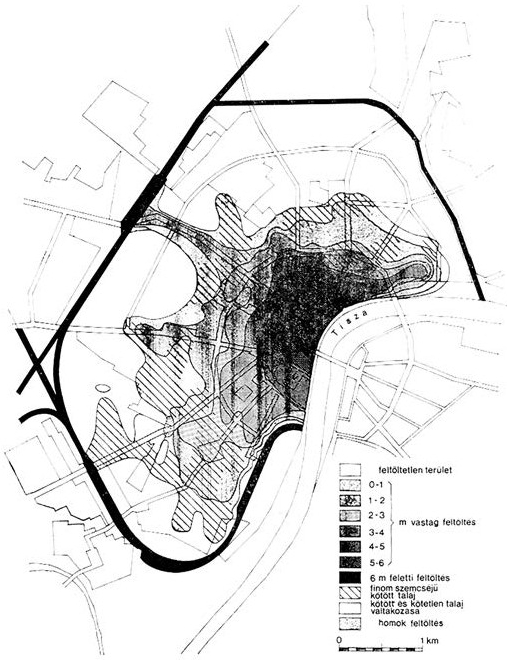

Since 1937, Hungarian regulations have required that town and city populations have at least 30 square meters of free cultivated area per person. In the planning of green spaces, Pálfy-Budinszky included unused elements that nature had already created: among them, lake and river floodplains, disused mines, and areas whose ground conditions are not conducive to construction, ensuring that large open spaces, including the circular embankment surrounding the city, could over time emerge by themselves.

In his 1938 study titled “Important Urban Planning Issues of Szeged,” Pálfy-Budinszky wrote, “Another problem in Szeged is that the immediate surroundings are extremely poor in landscape values…we are almost beggars in terms of plant elements and forests. …But let’s see, what would the city builder need to do here to turn the sad surroundings of this lowland metropolis into a charming Szeged, encircled by forests and gardens that refresh the body and soul? In any case, the first thing to be done is to preserve all the features that can be taken into account and to design them in accordance with their purpose. The Tisza River is the basic element and starting point of the whole open space system, and we can gain a lot of green spaces by using the circular embankment and the railway embankment and by afforesting them.”53

In the same year, László Gallé, a lichen researcher from Szeged, published “The Lichen Flora of the Szeged Circle Embankment.”54 Since 1926, Gallé studied the circular embankment’s lichen and moss vegetation, identifying 16 lichen species on the embankment’s iron-oxide-rich brick coverage, including some only rarely found on the Great Plain. He found that different plants, wheatgrasses, and perennials also covered the embankment’s inner edge. Whereas the inexperienced eye sees nothing, or at best unremarkable plants on the embankment, this 17-kilometer stretch was a paradise for Gallé. Pálfy-Budinszky may not have known Gallé, but Szeged’s circle embankment played a major role in their activities in the 1930s; both saw great potential and vital energy in it and considered it an unused, important, and untapped natural treasure. Taking up the challenge of Western urban trends, Pálfy-Budinszky included the circular embankment, originally defined as a border, as a foundational green belt in urban development.

Summary

In Szeged’s circle embankment, Pálfy-Budinszky found a coherent green belt that most aptly fits the ideal of an urban green space and a modern urbanistic vision. Márton Volford’s research for his thesis focuses on the current relevance of the embankment as a green space as initiated by Pálfy-Budinszky. Today, the people of Szeged believe that the circular embankment, like Vienna and Paris, contains an important element of modern cities today: the greenway. Nevertheless, the surrounding housing estates use the circular embankment in different ways. “The people who live inside use all the ways use it, while those living on the outside use a narrow strip of woodland and an iron and a thick brick wall. Today, the outer parts of the city are completely isolated from the inner city by the ring road, forced to pass through various gateways both by road and on foot. To create this transition and openness, on both road and on foot, various improvements will be necessary along the entire embankment and in certain sections. The aim should be to people and communities living outside the embankment not as a border, a dividing line but as an opportunity. Let them see the causeway and its surroundings an open public space that connects neighborhoods, a place where they can relax, enjoy walking 10 m above the level of the city, play sports. It should be a 12-km-long green ring road fully walkable, answering the most urgent question of today’s modern cities.”55

Endre Pálfy-Budinszky (1902–1968) engineer and lawyer. City engineer of the city of Szeged.

EKLER, Dezső and TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2016. Ringstraßen im Vergleich.: Varianten auf eine städtebauliche Idee in Wien, Budapest und Szeged. In: Hárs, E., Kókai, K. and Orosz, M. (eds.). Ringstraßen: Kulturwissenschaftliche Annäherungen an die Stadtarchitektur von Wien, Budapest und Szeged. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, pp. 25–62, here p. 38.

KOVÁCS, Krisztina. 2021. „Enyészet és feltámadás” – Megjegyzések a szegedi nagyárvíz történetéhez. Acta Historiae Litterarum Hungaricarum, 35, pp. 227–253 [online]. Available at: https://ojs.bibl.u-szeged.hu/index.php/ahlithun/article/view/34194 (Accessed: 16 November 2024).

TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2020. Little Vienna – Little Budapest: Ring Boulevards of Three Midsized Towns int eh Habsburg Empire, 1848–1920. In: Thomas, A. et al. (eds.). Yearbook of Transnational History 3. Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, pp. 33–54, here p. 22.

Lajos Lechner (1833–1897) engineer and urban planner, involved in the preparation of the first general planning of Budapest. The city of Szeged, destroyed by the flood of 1879, was rebuilt according to Lechner’s plans.

KÁROLYI, Zsigmond. 1969. Adatok a szegedi árvíz történetéhez. In: Károlyi, Zs. (ed.). Vízügyi Történeti Füzetek No 1: Az 1879-es szegedi árvíz. Budapest: Vízügyi Dokumentációs és Tájékoztató Iroda, p. 57.

NAGY, Zoltán. 1991. A Körtöltés és a város feltöltése. In: Gaál, E. and Kristó, Gy. (eds.). Szeged története 3/1. Szeged: Szegedi Nyomda, p. 176.

ÚJVÁRI, Edit (ed.). 2007. Szeged-Klebelsberg-telep története. Szeged: Klebelsberg-telepi Polgári Kör Közhasznú Egyesület.

BALÁZS, Imre. 2003. Béketelep története. Szeged: Bába és Társai, p. 9.

SIPOS, András. 2005. Budapest városfejlesztési programja, 1930–1948. Múltunk – Politikatörténeti folyóirat, 50, pp. 157–159.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1938a. Szabadterületek, zöld területek. Szeged városépítési problémái. Inv. no. XB 198346. SZTE – Klebelsberg Library, Szeged.

BIERBAUER, Virgil. 1933. Budapest várostervezési problémái. Tér és Forma, 6, pp. 273–288.

BERZENCZEY, Domonkos. 1932. Az Alföld várostervezési problémái. Városkultúra, 8, pp. 9–14.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre and HERGÁR, Viktor (eds.). 1934. Szeged városépítési problémái. Szeged: Magyar Mérnök és Építész Egylet Szegedi Osztálya Szegedi Alföldkutató Bizottság.

Sándor Bálint (1904–1980) ethnographer from Szeged.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1976. Szeged városközpontjának fejlődése és a Széchenyi tér kialakulása. Inv. no. B. 83-84. Ferenc Móra Museum, Sándor Bálint bequest, Szeged.

PÉTER, László. 1987. Bálint Sándor pályája. Tiszatáj, 8(41), p. 23.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1931. Gondolatok a városrendezés és a korszerű lakásépítés gazdasági és szociális jelentőségéről 1–2. Szegedi Szemle, 4–5.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1933. Szabad és zöldterületek szerepe a városépítésben: a szegedi városépítési ankéton elhangzott előadás 1–4. Városkultúra, 6(8–12).

Pál Ligeti (1885–1941) architect and art writer.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1936. Kerékpárutak városépítési vonatkozásai. Városkultúra, 9(1–2), pp. 37–41.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1933. Városrendezési előadások. Délmagyarország, 11 March 1933, p. 5.

WÖLFFLIN, Heinrich. 1886. Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur. Munich: Kgl. & Universitäts-Buchdrukerei von Dr. C. Wolf & Sohn.

Otto Robert Bünz (1881–1954) German architect and author.

An urban planning movement in the 20th century.

MOLNÁR, Dezső. 1942. Szabad területek és nagyvárosrendezés. Magyar mérnök, 76, p. 126.

BIERBAUER, Virgil. 1938. Várostervezési problémák. Vállalkozók Lapja, 59(1–4), p. 5.

MORBITZER, Dezső. 1937. Városépítészet és kertészet. Városi Szemle, 23, pp. 103–161.

RANSCHBURG, Pál. 1933. Csend és idegrendszer. Városi Szemle, 19, pp. 418–485.

Morbitzer, D., 1937.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1938a.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1938a, p. 18.

BALOGH, Péter István. 2004. A szabadterek szerepváltozása a nagy európai városmegújításokban. PhD thesis. Corvinus University, Budapest, pp. 7, 11, 49. Available at: https://phd.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/485/1/de_1660.pdf (Accessed: 16 November 2024).

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1939. Szabadterületek. Városok Lapja, 20, pp. 407–409.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1934. Szabadterületek és zöldterületek. In: Hergár V. (ed.). Urban planning problems in Szeged. Szeged, p. 149.

Péter Balogh cites: GRANASZTÓI, Pál and HELLE, László. 1954. Currently used nomenclature of urbanism [manuscript]. Budapest: Urban Planning Company.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1933. A szabadterületek és zöldterületek szerepe a várostervezésben. Városkultúra, 6(6–9).

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1933, 4, p. 141.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1933, 4, p. 142.

See in his later writing in more detail: PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1940. A városkörnyék-vizsgálat szerepe a városépítésben. In: Városfejlesztés, városrendezés, városépítés. Budapest: Állami, pp. 227–239.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1933, 4, pp. 145, 147.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1937. Kerékpárutak városépítési vonatkozásai. Szeged: Traub, p. 31.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1934, pp. 141–163.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1934, p. 149.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1934, p. 161.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1940. A városkörnyék rendezésének szerepe a várostervezésben [manuscript]. Inv. no. D1631. Somogyi Károly City and Regional Library, Szeged.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1941, p. 115.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1941, p. 116.

Pálfy-Budinszky, E., 1941, p. 116.

KARANCSI, Zoltán, SZALMA, Elemér, OLÁH, Ferenc and HORVÁTH, Gergely. 2016. A városi parkok és szerepük az idegenforgalomban Szeged példáján. In: Pajtókné Tari, I. and Tóth, A. (eds.). Magyar Földrajzi Napok 2016. August 2016. Hungarian Geographical Society, Agria Geográfia Foundation, Eszterházy Károly University, pp. 695–708.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1938c. Szeged fontosabb városépítési kérdséei. Sopron: Rábaközi Nyomda és Lapkiadó Vállalat, p. 15.

PÁLFY-BUDINSZKY, Endre. 1938c. Szeged fontosabb városépítési kérdséei. Sopron: Rábaközi Nyomda és Lapkiadó Vállalat, p. 15.

GALLÉ, László. A szegedi körtöltés zúzmóflórája. Inv. no. XB 197046. SZTE – Klebelsberg Library, Szeged.

VOLFORD, Márton. 2021. A szegedi Körtöltés – Határ az átmenetben. PhD thesis. Department of Urban Studies, Budapest University of Technology.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2024.58.3-4.9

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License