Frequently compared to Vienna’s Ringstrasse, the Brno ring boulevard must nonetheless – despite the shared association with Ludwig Förster – be considered a completely unique urban development, dating to the end of the 18th century. Competition proposals for the design of the Brno ring boulevard predetermined the final form of the regulatory plan, which was used for the the curving boulevards constructed between 1863 and 1885. Although it might appear that Brno’s ‘ring’ was already complete in the 19th century, the 20th century was the time to see the greatest architectural change. The story of the ring boulevard began with Napoleon, and even after 200 years, its development is ongoing.

A Brief History of the Brno Urban Fortifications

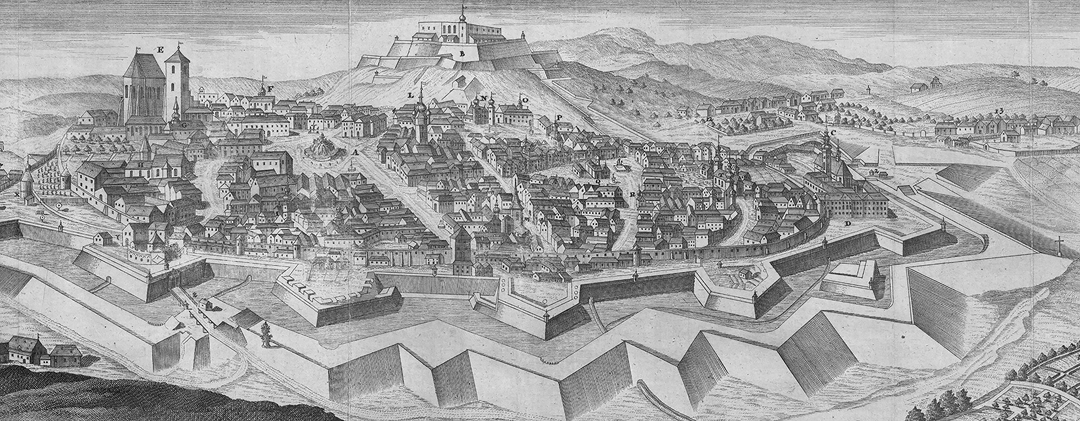

In 1243, the city of Brno received from King Wenceslaus (Václav) I. the privilege to protect itself with fortification walls. Several decades later, the royal castle Špilberk, which dominates the city from its commanding position, was constructed, and primarily served as the residence of the Margraves of Moravia from the House of Luxembourg.1 The medieval city fortifications featured five gates, each leading to two streets, which branched towards one of Brno’s three2 marketplaces. The only gate to survive to this day is the (New) Měnínská Gate; the original, older Měnínská Gate, situated further north, was deemed unsuitable due to its narrow profile and subsequently converted into a pedestrian gate. On the southern side of the city, the Jewish Gate stood until the 19th century. The Brno Gate was on the western side towards Pekařská Street and Old Brno. On the northern side, there were two gates: Veselá and Běhounská. Suburban development emerged along the roads at varying distances from the city walls. Just beyond the walls at the Běhounská Gate, an Augustinian monastery with the Church of St. Thomas was established in 13503; after its fortification in 14864, it became part of the inner city. With the advent of firearms, the Renaissance period saw an increase in the number of gate towers and the addition of barbicans.

The 17th century brought Europe its longest5 modern conflict. In the final decade of the Thirty Years’ War, Moravia was invaded from the north. Swedish troops approached Brno in 1643, leading to the burning6 of Brno’s suburbs for defensive reasons. Another encounter with the Swedes occurred two years later in 1645, during their attempt to conquer Vienna. Anticipating the enemy’s advance, the city promptly repaired the walls and deepened the moats7. Brno’s proven strategic importance in protecting Vienna led its declaration as a fortress city, as well as assuming the status of the regional capital8 of Moravia. The effectiveness of Brno’s fortifications resulted in the gradual transformation of the city into a Baroque fortress with a citadel9 at Špilberk Castle. Construction of the bastion fortress progressed slowly, accelerating only after the Turkish and Tatar invasions of Moravia in 1663.10 Built in two stages, the fortress consisted of a higher inner zone of walls, including a broad water moat, further surrounded with eight pentagonal bastions. Of the original five city entrances, only three remained in the new fortification system: the Brno Gate towards Old Brno and Pekařská Street, the Jewish Gate on the southern side, and the New Veselá Gate located in the barbican wall between the first and second bastions. This first stage of construction was completed in the 1680s.11 The medieval fortification system was almost entirely dismantled, with the moats filled in.12 All that survived of it were the walls between the seventh and eighth bastions under St. Peter’s Hill (Petrov) and between the eighth and first bastions, between the city and the slopes of Špilberk.

The second stage of building the Baroque city fortress commenced in the mid-18th century, now involving a low belt of fortification with counterscarp and earthen ramparts. It was, in fact, the resulting wide undeveloped strip of land along the walls, known as the glaci13 [Czech: koliště], that determined the route and width of the later constructed ring boulevard. In turn, the need to connect the city with its growing suburbs led to the construction of additional gates. In 1744, the Hackel Gate was established by the first bastion, leading to the village of Švábka (now Údolní Street). Although the gate served internal city traffic, it was often kept closed.14 Though usually associated with the modernization of the state bureaucracy and introduction of a postal service, the reign of Maria Theresa also brought the construction of imperial roads. Along with new routes from Vienna to other imperial cities, a ring road was built in Brno between 1774 and 177615, allowing transit traffic to bypass the medieval street network of Brno. This ring road (now Koliště Street), consisting of angled straight sections, extended from the northern New Veselá Gate around the eastern edge of the glacis to the southern Jewish Gate. Additionally, its construction led to a new passage being created through the wall at the site of the old Měnínská Gate; placed in front of the fourth bastion, this gate opened directly to the older suburb of Cejl. In 1793, the abandoned and militarily obsolete glacis was converted into a promenade with an avenue of lindens, initiated by Governor Count Alois Ugarte.

The New is in the Old

If the early 19th century was primarily marked by the expansive campaigns of Napoleon’s forces across the European continent, Brno was no exception. Emperor Napoleon first visited the city before the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, during which he ordered the construction of new palisades and reinforcement of the walls at Špilberk Castle. His return after four years, however, was marked by demolition: on 28 October 1809, the French destroyed the Špilberk Citadel.16 This act of de-fortification had a significant impact on the future development of the circular boulevard, as the outer bastion ring around the city was dismantled, a destructive intervention in the fortification system that, in turn, stimulated new speculations on the further utilisation of the Baroque fortifications. The damaged Bastion No. VIII, situated beneath St. Peter’s Hill, was landscaped in the English style, and in 1813, a Neoclassical structure known as the Fons Salutis17 (Spring of Health) was built on the slope towards Old Brno. The small park was named Franzensberg18 (Františkov) in honour of the Austrian Emperor Francis I. In 1818, an obelisk was erected on the platform of the demolished bastion, serving as the Peace Monument to mark the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Designed by Alois Pichl, this monument became a significant feature of Brno’s skyline for many decades19 and later a crucial urban element of the future city boulevard.

Despite the establishment of a public20 park at a greater distance north of the city, the inhabitants desired a promenade closer to the city. This demand led to the restoration of the promenade avenue through the moat, extending once again from the Jewish Gate in the south to the Veselá Gate in the north.21 Alongside the adaptation of the moat’s foreland, the internal areas of other bastions and the spaces along the curtains were modified in a similar manner to Bastion No. VIII.22 To commemorate the accession of the new monarch, a new Ferdinand Gate was constructed on the site of the Jewish Gate, designed as a triumphal arch flanked by guardhouses.

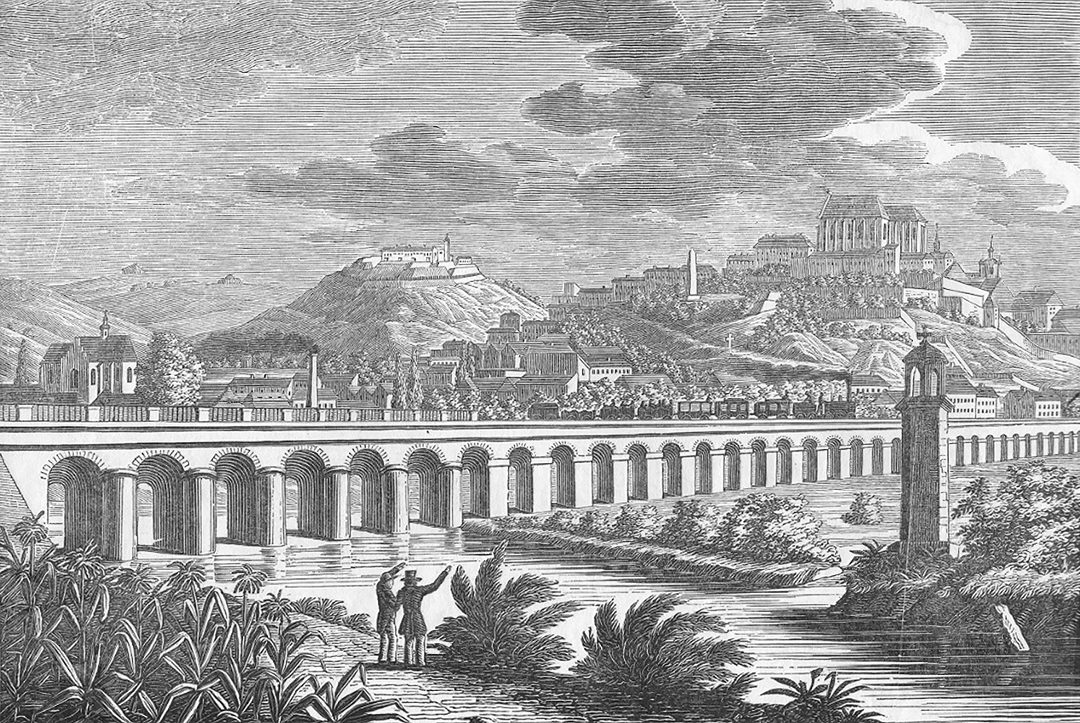

The construction of one of Europe’s oldest rail lines,23 connecting Vienna and Kraków, provided a significant impetus for the development of the Brno region. In 183924, the first steam train arrived in Brno from Břeclav. Due to the Svratka River basin, it was necessary to connect the railway to the city via a 637-meter-long viaduct25. The Emperor allocated fortification land between the new Ferdinand Gate and the park at Františkov (near Bastion VII) for the construction of the railway station. Although the plan assumed a terminus station, the railway curved away from the fortifications, positioning the platform parallel to the city walls. This alignment allowed for the extension of the line towards Česká Třebová and Prague, seamlessly connecting to the existing railway infrastructure. However, the station building, originally constructed perpendicular to the tracks, presented a hindrance. Consequently, the old terminus station had to be replaced after just ten years by two26 new buildings situated in front of Bastions V and VI. Realisation of the joint station concept is credited to chief building director Josef Esch.27 Additional fortification land between Bastions IV and VI was allocated for railway infrastructure needs, necessitating an elevated terrace and, regrettably, the loss of the recently created parkland.

The renewed unrest in France, culminating in the July Revolution of 1830, halted the plans28 of the Austrian military authorities for demolishing the baroque fortifications, the German-speaking core of Brno as a closed29 fortress city. In contrast, the Theresian and Josephine30 reforms31 of the 18th century spurred rapid development in the Czech-speaking suburban municipalities, which expanded32 disproportionately and merged into agglomerations of small-scale buildings33 around manufactories and factories. Thus, beyond the city walls, a wild era of emerging capitalism began, while the constricted and cramped city itself long sought to acquire military land for its expansion. Urban modifications in the spirit of the new century commenced with the demolition of the still-medieval fortifications between the old Jewish Gate and Petrov. Along this line, likely in conjunction with the building of the railway station, a row of apartment buildings emerged between 1838 and 1839 along the rising terrace, including the grandly designed Padowetz Hotel.34 In 1843, the idea of expanding the city westward and northward was conceived. This proposal was further developed in 1845 by Josef Esch, Head of the Provincial Building Directorate [Landesbaudirektion] at the Moravian Governorate.

The “Plan for the Expansion of the Inner City of Brno”35 envisaged two intersecting, mutually perpendicular boulevards – an ambitious compositional cross. The east-west axis was to begin at the façade of St. Thomas’s Church, while the north-south axis was to start at the Pichl Obelisk in Františkov. Due to the lack of space within the inner city, Josef Esch proposed constructing block developments for new offices, schools, and residential buildings on both sides of the emerging urban streets. These were to be built on the site of the First and Second Bastions, following the demolition of the Baroque New Veselá Gate36 and adjacent barbican walls. The quadrangle of the former37 Augustinian monastery was to be aligned with new buildings of the Moravian Governorate up to the façade of the church. Closing the resulting square on the northern side would be a new Veselá Gate — a triumphal five-arched passage with flanking guardhouses and a colonnade.38 At the same time, the Brno Gate and Hackel Gate would be demolished and replaced with a three-arched wrought-iron gate with intermediate pylons.39 New military headquarters, a gymnasium, and a polytechnic were to be positioned along the axis of St. Thomas’s Church. In the second axis, leading towards the Peace Monument, residential buildings were to be constructed. Esch anticipated the development of the then bare40 and steep slope of the Špilberk Citadel. In this context, it was also planned to remove the forward-set fortress of Hornwerk, which had been functioning as a women’s prison since the late 18th century.41 Esch’s plans were submitted to the court office in 1847, which approved the development along the axis of St. Thomas’s Church on the condition that Brno would remain a closed city, akin to Graz in Styria. Buildings facing the moat would thus have no entrances on this side, and windows up to the second floor were to be barred. The military commission opposed construction on the slope near the citadel.42

Again, the implementation of the approved plan was thwarted by political turmoil, in this case the revolutionary year of 184843. Significant development for the city came with the administrative expansion44 of Brno in 1850, approved by the new emperor, Franz Joseph I, in which the city annexed its previously independent suburbs, despite their continued separation by the Baroque bastion walls. A pivotal moment in the development of modern Brno occurred on 25 December 1852, when the emperor decreed that Brno would cease to be a closed city (though Špilberk Castle remained a military citadel).45 Specific conditions for the transfer of fortification lands were announced by the military command in 185346: For instance, that part of these lands remain undeveloped for health and public reasons, space be reserved for military parades, compensation provided for all removed military buildings and fortification structures.47 These conditions led to prolonged negotiations, resulting in a halt to the demolition work and suspension of the construction of new buildings following Esch’s approved plan. Paradoxically, this delay in the city’s redevelopment greatly benefited Brno, helping it avoid the speculative building frenzy that would affect Prague 14 years later.48 In 1853, a regulatory commission was established, led by the governor Count Leopold Lažanský, to oversee the demolition of the walls and the new construction.

A Journey around the City

Immediately, demolition of the city fortifications began. Between 1849 and 1851, the Brno Gate and other dilapidated structures, including the medieval defensive walls, disappeared. According to the approved Esch development plan, the Municipal Tenement House [Stadthof]49 was constructed between 1853 and 1855, following a design by Franz Frölich. This prominent four-winged residential block was built on the site of the original upper malthouse50, and its modern layout, featuring several staircases, comfortably served the multi-room flats. Its orientation also firmly established the north-south axis of the future boulevard Elisabethstrasse51 (now Husova Street) for further construction.

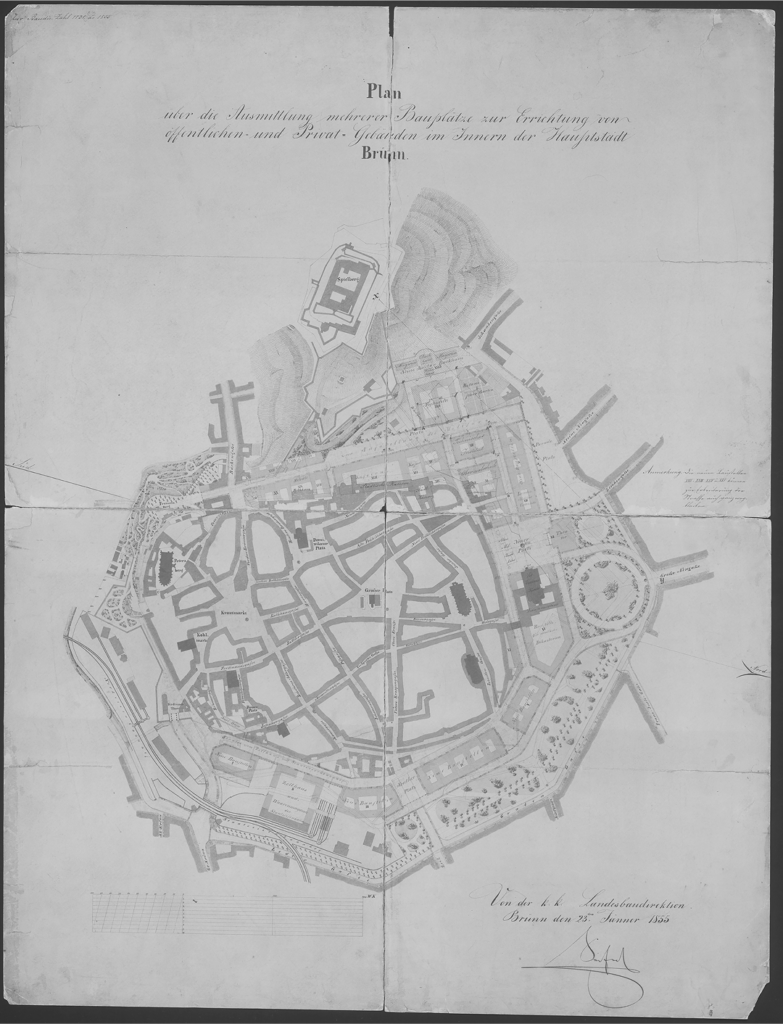

In 1855, a new “Plan for the Creation of Further Building Sites for the Construction of Public and Private Buildings in the Inner City of Brno”52 was developed. The author of this development plan was Joseph Seifert, Esch’s successor in the office of the Provincial Building Directorate, who could now make use of all the land surrounding the city that had been freed up by the demolition of the fortifications. While Seifert to some extent respected Esch’s design for the western side of the city, he adjusted it in response to the criticisms of the military command. For the first time, the plan depicted the idea of a ring boulevard, as was eventually realised: on the western side, it was formed by a single boulevard at the foot of Špilberk; on the northern and eastern sides, it consisted of parallel boulevards with a park promenade; and on the southern side, due to the earlier expropriation of fortification land by the railway, it was again only a single boulevard. Although Seifert’s design called for the removal of the Baroque bastions, it continued to separate the inner city from the park belt at Koliště with fencing, fulfilling one of the military command’s conditions.

Between 1858 and 1860, the Technical College53 was built near the Hackel Gate and the First Bastion, still outside the city walls, despite demolition54 beginning near the Brno Gate almost a decade earlier. The new building openly clashed with Seifert’s regulatory plan, which proposed a military parade ground and adjacent command structures in this area.55 Moreover, the placement of the college building, with its setback from the street, predetermined the existence of a square in this area. Due to the premature death of Joseph Seifert and the final decision that Špilberk would cease to be a provincial fortress (185956), there was no up-to-date, realistic project for further development. Governor Lažanský proposed that the city draft another57 regulatory plan and recommended consulting the Viennese architect and urban planner Ludwig Förster58, the author of the successful 1858 competition design for the redevelopment of the Vienna glacis, which became a significant foundation for the realised Ringstrasse project.59

Ludwig Förster’s regulatory plan60 for Brno was developed very quickly, and he submitted his design just a few months after its commission in 1860. He approached the city and its surroundings comprehensively, including the design of newly opened or at least widened streets within the still-Baroque inner city. Förster drew heavily from Seifert’s plan, featuring a boulevard of angled segments rather than curves, block-based development, and a connecting green park belt emerging from the original glacis. He regarded the main entrance to the city as being primarily the point of the railway station, where he supplemented the forecourt with a line of new buildings and a new hotel aligned with the axis of the railway bridge. With the construction of a boulevard beneath the slope of Špilberk already initiated, in view of the newly relocated technical school, he proposed the symmetrical expansion of the site with an elongated square, terminating at the northern end with the existing suburban development. The second perpendicular axis, leading to the facade of St Thomas’s Church as in previous plans, was terminated by a square at the Governor’s Palace. On its northern side, in place of Seifert’s proposed theatre, he placed a restaurant, relocating the theatre to the site where it remains today. It is evident that Förster sought a balanced distribution of landmarks around the entire city.

However, the inability to coordinate the efforts of various levels of urban administration resulted in the District I Committee61 (Inner City and Špilberk) commissioning the city engineer, Johann Lorenz, to develop an alternative design. The Brno City Council, represented by the municipal committee, then awaited its completion to decide whether the two designs could be combined or if a formal competition should be announced.62 Lorenz’s design63 largely mirrored Förster’s, although it did not address the redevelopment of the inner city. Lorenz proposed expanding the green belt at the expense of the width of the perimeter block development, bringing it closer to the city, and introduced the concept of a northern communication bifurcation in front of the Governor’s Palace.

For unclear reasons, only Lorenz’s design was presented to the public, sparking sharp criticism of the town council for their peculiar actions.64 In 1861, Mayor Christian d’Elvert finally pushed through the announcement of a public competition, from which fifteen designs emerged.65 The winning design, marked as “F”66, was submitted by the Brno-based architects Moritz Kellner and Franz Neubauer, with second place awarded to the Brno builder Josef Arnold. The winning design67 was particularly noteworthy for its entirely different perspective on the layout of park areas. While the previous three regulatory plans consistently adhered to a continuous tree-lined promenade, the competition winners placed park squares perpendicular to the boulevards, thereby connecting the inner city with the suburbs through green spaces. The new block construction in the design extended up to the outer ring road dating from the 18th century.

The entirely different views on the development of the areas surrounding the city led to the establishment of a technical committee, composed of the authors of the first and second-placed designs, tasked with merging the two designs. In 1862, the so-called “combined” plan was submitted, which, upon its publication, sparked a wave of discontent.68 The people of Brno were particularly incensed by the idea of expanding block construction at the expense of the city’s green park areas, particularly since more building plots meant more money for the city treasury from the sale of building land. Outraged, they demanded the return of their landscaped bastions and the opportunity to promenade in the tree-lined boulevards around the city. In response to public pressure, the Brno town council established a new committee with the task of respecting the “demands of the public and public opinion”69 and drafting a “final” plan70. This plan was presented to the public in 1863 and was indeed the last of six plans created over the previous eight years. Developed by Franz Neubauer, it slightly modified Förster and Lorenz’s design while additionally adhering to the final decision to place the Protestant church at the head of Esch’s north-south axis. Although this disrupted the continuity of the ring boulevards, the city’s gains were perhaps greater – with the church forming a dignified counterbalance to the obelisk located at the southern end of Brno’s first boulevard. Brno’s “greenery architect,” Mayor d’Elvert, also ensured that the revised plan included the extension of the perpendicular boulevard towards St. Thomas’s Church to allow for the planting of a multi-row tree-lined boulevard.71

Realization of the Ring Boulevard

The regulated construction of buildings and the development of areas based on the “definitive” regulatory plan began in 1863. Subsequent plans72 delineated building plots for sale but no longer specified their use in detail – the “definitive” plan was only reflected in the most basic outlines during implementation. For example, the theatre building was constructed according to the position outlined in Förster’s plan. Although there was no rush to build the theatre, the process was hastened by the fire at the old theatre on Zelný trh in 1870: a temporary wooden theatre was raised in front of the Church of St. Thomas, on the site of several yet undeveloped plots, and work on the permanent masonry theatre was expedited. Designed by the renowned Viennese architectural duo Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, this structure was constructed between 1881 and 1882, and was the first in Europe to install Edison’s electric lighting.73 The basic framework of the ring boulevard was completed in 1885. In addition to newly built school buildings and residential palaces (e.g., of the Kounic, Doret, Kelner families), the most prominent construction was the new Regional Building: designed in highly monumental Neo-Renaissance style and built next to the Evangelical Church, it was intended for the meetings of the Moravian assembly. At the turn of the century, Brno experienced a wave of urban renewal – new streets were laid out through the extant urban fabric74, street alignments were adjusted, and new buildings were constructed, all of which contributed to the improved appearance of the ring boulevard.

With the establishment of the independent Czechoslovak Republic in 1918, and the subsequent administrative expansion of Brno a year later75, Czechs regained dominance in the governance of the city, overtaking the Germans after several centuries. Until that time, it was very difficult for Czech architects or builders to implement architectural projects in the inner city.76 During the First Republic, several older buildings were either reconstructed in the spirit of modern architecture or entirely replaced with new constructions. An example of this is the redevelopment of the Doret Palace opposite the city theatre. Its rear, single-storey variety section was replaced by the Functionalist, seven-storey Morava Palace, while later, the original Neo-Renaissance façade of the Doret Palace was itself modernised to suit the needs of the Regional Insurance Company. The architect responsible for these modifications in both instances was Ernst Wiesner, a prominent Brno-based architect. Although the concept of a continuous connection of ring boulevards had appeared in competition proposals as early as the 19th century, its realisation in Denisovy sady, beneath the obelisk, did not occur until the German occupation in the 1940s. Following a series of bombings in Brno towards the end of the Second World War, a residential block on the northeastern edge of the city was hit. Gradual demolition of these damaged buildings freed up space that attracted the interest of architects, who then relocated their vision for a national theatre (the future Janáček Theatre) to this area.

The transportation of people and the movement of goods have always been driving forces in historical development. In Brno, it was the interwar Functionalist architects who first addressed with this issue cohesively, viewing the old railway station in the city centre as a barrier to further urban development. Although the Brno architect Bohuslav Fuchs77 later questioned the appropriateness of the previously advocated relocation78, the idea has persisted and remains a consistent element in all of Brno’s urban planning for nearly a century. Currently, the construction of a new station is taking on more concrete form, and the question arises whether, by the 2030s, the site of the old station will be transformed into revitalised parkland or commercial developments.

As early as the 18th century, an imperial road was constructed on the outskirts of Brno’s glacis to facilitate transit traffic. Although this road has traditionally marked the boundary between the city and the suburbs, the dramatic increase in vehicular traffic during the last century has turned it into a genuinely impassible barrier in the form of a four-lane urban ring road. In turn, this surge in automobile traffic has profoundly influenced the character of the city’s streets, which had to be widened to accommodate it at the expense of pavements, and the original tree-lined avenues were replaced by rows of parking spaces. The existence of the original promenade (marked as Ringstrasse in Förster’s plan) stretching from the Theatre (now Mahen Theatre) to Moravian Square [Moravské náměstí] can no longer be found along today’s Za divadlem Street, which has been converted into a car park. Furthermore, its natural continuation was entirely disrupted by the construction of the expansive Janáček Theatre during the 1960s.

Is Brno a Clone of Vienna?

Within the Austrian Empire, which was divided into several hereditary lands, the Margraviate of Moravia with its capital Brno was the closest to the imperial capital city of Vienna – only 110 km away as the crow flies (compared to Graz at 145 km, Linz at 155 km, and Prague at 250 km). This proximity is why so many Viennese artists and architects worked in Brno and why the Brno ring boulevard is so easily compared to the similar boulevard in Vienna. However, this resemblance originates from different foundations and has its specific and unique origin.

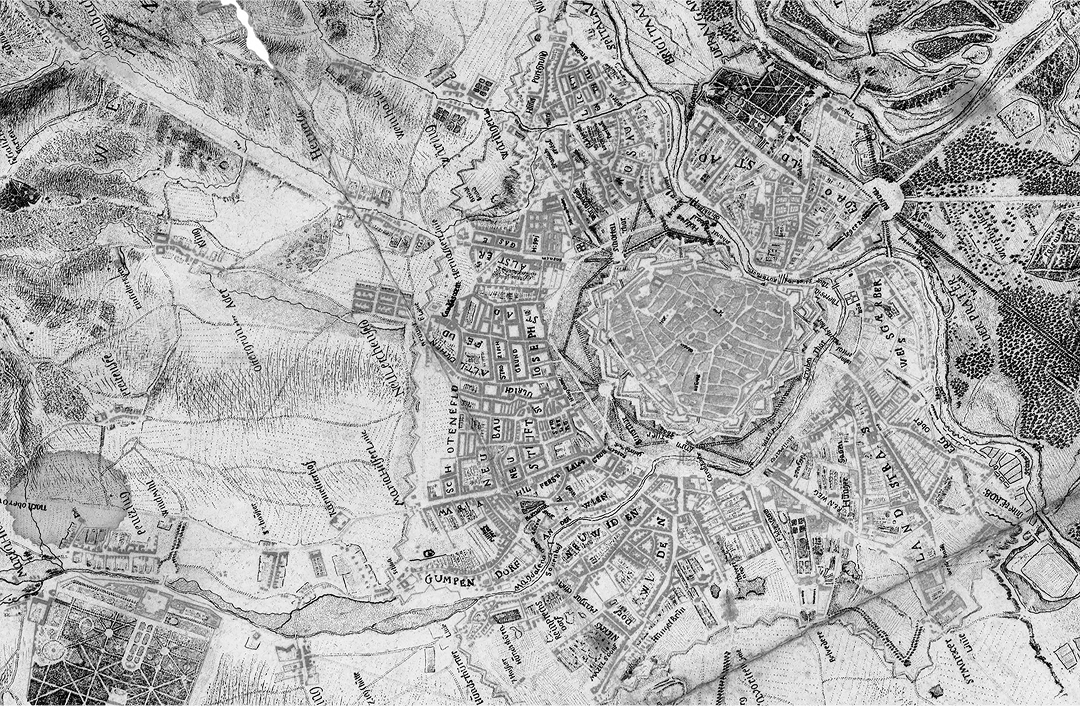

The population ratio of Brno and Vienna remained nearly constant despite the growth of these cities during the first half of the 19th century. In 1804, Brno had a population of 25,295, while Vienna’s population was approximately 260,000; by 1834, Brno’s population had risen to 36,707, while Vienna’s was 326,353; in 1846, Brno registered 45,189 inhabitants, compared to Vienna’s 407,980 (for comparison, Prague had 115,436 inhabitants). The area within the Baroque fortifications of Brno covered 0.44 km2, whereas Vienna’s covered 1.23 km2. From these figures, it is evident that although the enclosed area of Vienna was only three times larger than that of Brno, Vienna’s population was nearly nine times greater. This significant discrepancy indicates that by the mid-19th century, Vienna already had a densely urbanised and extensive area of outer suburbs, which formed a continuous urban fabric beyond the glacis area (already landscaped into a parkland by that time). Brno, by contrast, had nothing even approaching a similar extent.

From the 18th century, an imperial ring road was gradually established along the edge of Brno’s glacis at a set distance from the city walls, with single-sided development extending along this route, linking to Brno’s older suburbs. The free spaces of the glacis, bordered by the road in Brno and by suburban buildings in Vienna, were similarly polygonal in layout around the Baroque-fortified city. This delineated area was 0.4 km2 with 2 km of walls in Brno and 1.8 km2 with 4 km of walls in Vienna. It follows that the glacis area, relative to wall length, was over twice as large in Vienna as in Brno. Additionally, the Baroque fortification of Vienna featured more bastions, ravelins, and counter-escapes, making it more spatially demanding. The width of undeveloped land from the Baroque curtain walls to suburban buildings was 450–580 m in Vienna, compared to only 150–200 m in Brno.

Due to Vienna’s extensive suburban area, this development was protected by an additional defensive wall, known as the Linienwall. Built in the early 18th century initially in the form of earthen ramparts, these were later reinforced with a brick escarpment, located 1.6–2.9 km from Vienna’s original medieval walls. The existence of this wider fortification around the capital prevented the new construction of rail infrastructure, whether rail lines or stations, from reaching Vienna’s historic core, so the undeveloped glacis area was not utilised by the railway as it was in Brno. In 1858, a competition was held in Vienna for the comprehensive urban planning of the area between the historic core – now free of its Baroque walls – and the edge of the suburban buildings. Ludwig Förster won this competition with his proposal for a broad, six-sectioned boulevard positioned centrally on the glacis (now the Ringstrasse). Given the width of the planned area, the boulevard was supplemented by additional parallel streets. The connection between new buildings and the existing suburban fabric was natural, given the urban character of Vienna’s suburbs.

The situation in Brno, however, was entirely different. Of the same six arms as in Vienna, two orthogonal axes were already under construction, and two segments were occupied by the railway station. Thus, in Brno’s competitions, only the remaining two arms on the eastern side of the city were actually addressed, with only minor adjustments to the other segments.

A comparison between Brno and Vienna is logical, as the two cities have an undeniable relationship. However, any underlying similarity in their ring boulevards primarily stems from the standardized character of Baroque fortifications, where the extended barbican walls provided the foundation for the polygonal layout of future ring roads. Additionally, the timing of redevelopment in both cities coincided with the defortification process, and both cities shared the involvement of Ludwig Förster, the common designer of regulatory plans. While Förster saw his proposal realized in Vienna, in Brno his design was repeatedly reworked, perhaps even forgotten, with the so-called “final” plan serving as the basis for implementation – a plan that only vaguely respected some of Förster’s ideas. While Vienna’s Ringstrasse represents the rigorous execution of an authorial design, Brno’s ring road reflects the gradual efforts of the city council to expand a medieval city confined by walls. Thus, comparing these two ring boulevards is not appropriate, and insisting on the legacy of a renowned urbanist in provincial Brno seems more an attempt to elevate this ring-road experiment to the level of the imperial capital’s Ringstrasse.

Conclusion

In European cities, circular belts of urban parkland typically emerged in areas previously occupied by complex Baroque fortifications, including moats and ramparts. The width of these defences established a long-standing undevelopable zone between the stagnant fortified city and the burgeoning suburbs. By the 19th century, advancements in artillery had rendered these military fortifications obsolete, prompting city officials to vigorous activity toward liberating themselves from the constraints of a closed city. Brno was fortunate in that it, like the capital of the monarchy, “opened up” at the same time, with the young monarch being remarkably generous under the prevailing conditions. Unlike Prague, which had to repurchase the fortification lands later and at a high cost, the lands were practically given to Brno and Vienna as a gift.79 It is therefore surprising that, under these favourable conditions, Brno, unlike Vienna, contributed so little to the development of new municipal buildings.80 Apart from the municipal theatre and two schools, neither a new town hall nor a city library was constructed.

Although at one stage of its design development, the ring boulevard was associated with the well-known Viennese architect Ludwig Förster, it must be regarded as a distinctly independent urbanistic achievement. Comparisons to Vienna’s Ringstrasse may be justified given the use of similar elements, but considering the relative sizes of the two cities, such comparisons almost invariably fall short. The development of Brno’s ring boulevard was complex and occurred gradually, as permitted by the military authorities. It is not the realisation of a single specific plan but rather a reflection of modifications that respect previous partial implementations. Additionally, the historical record reveals how the citizens of Brno demonstrated their ability to fight for their interests during this process, as they were successful in preserving the original size of the park areas.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, numerous other regulatory plans were proposed, although most remained unexecuted. Fortunately, in contrast to Prague, relatively little of Brno’s medieval core was demolished according to the city’s redevelopment plans81. It was, though, the Baroque palaces of the nobility became the primary victims of inner-city redevelopment, such as the Belcredi Palace on the Great Square (now Freedom Square), which was demolished to make way for a newly established street.82 Perhaps it is for the best that not all of these drastic architectural plans were fully realised. As an unfinished work, it retains the diverse imprint of the original, thus preserving the awareness of the rich history of the place.

VANĚK, Jiří. 2015. Hrad Špilberk. In: Kroupa, J. (red.). Dějiny Brna 7, Uměleckohistorické památky, historické jádro. Brno: Statutární město Brno, p. 117.

The largest public space in medieval Brno was the Lower Market (now Freedom Square), followed by the Upper Market (now Cabbage Market) and the Fish Market (now Dominican Square). The Coal Market (now Capuchin Square) was insignificant in comparison.

ŠEFERISOVÁ LOUDOVÁ, Michaela and KROUPA, Jiří. 2015. Kláštery ve města II. (severní část). In: Kroupa, J. (red.). Dějiny Brna 7, Uměleckohistorické památky, historické jádro. Brno: Statutární město Brno, p. 403.

PEŠA, Václav and DŘÍMAL, Jaroslav (eds.). 1969. Dějiny města Brna. 1. díl. Brno: Blok, p. 138.

The Dutch Revolt, also known as the Dutch War of Independence, is deliberately omitted here. It took place from 1568 to 1648, making it indeed the longest military conflict of the modern era. Given the number of parties involved and the loss of life, the second longest conflict, the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), is considered the longest.

The city defenders burned or demolished houses near the city fortifications for a strategic reason. These buildings made it difficult to see in front of the walls, and they provided the Swedes with footholds that allowed them to advance more easily and with cover during combat operations.

ŠUJAN, František. 1898. Švédové u Brna roku 1645. Brno, pp. 31–33.

Brno became the capital of Moravia in 1641, replacing Olomouc due to its strategic security after the Thirty Years’ War. Olomouc had been weakened by the Swedish siege, while Brno successfully resisted. Most of the provincial offices were then moved to Brno, solidifying its role as the administrative centre.

Derived from Italian, the word citadella means “city fortress”, i.e., a small fortress in a city with an armed military garrison. Two examples are Špilberk in Brno and Vyšehrad in Prague. See: SYROVÝ, Bohuslav. 1973. Architektura. Prague: Státní nakladatelství technické literatury, p. 57.

KUČA, Karel. 2000. Brno–vývoj města, předměstí a připojených vesnic. Prague: Baset, p. 67.

Kuča, K., 2000, p. 71.

ŠUJAN, František. 1928. Dějepis Brna. Brno: nákladem Musejního spolku, p. 296.

Wooden stakes and palisades were placed in the area of the low earthwork (glacis).

HÁLOVÁ-JAHODOVÁ, Cecilie. 1975. Brno, dílo přírody, člověka a dějin. Brno: Blok, p. 127.

Šujan, F., 1928, p. 336.

Peša, V., 1969, p. 197.

Kuča, K., 2000, p. 94.

Since 1918, the orchards have been named after the French historian Ernest Denis (1849–1921), a prominent supporter of the establishment of independent Czechoslovakia.

The obelisk’s dominant position in views of Brno was undermined at the beginning of the 20th century by the addition of the Gothic towers to St. Peter’s Cathedral.

In 1786, Emperor Joseph II decreed the opening of the Jesuit Charles Court to the public, which became the Augarten Park (today Lužánky) and was handed over to the public for its use, thus making it the oldest publicly accessible park in the territory of Czechia.

NOŽIČKA, Josef. 1962. Snahy o zkrášlení Brna a rozhojnění jeho zeleně. In: Brno v minulosti a dnes: sborník příspěvků k dějinám a výstavbě Brna, IV. Brno: Krajské nakladatelství, p. 182.

NEUHOFER. 1844. Provinzial-Hauptstadt Brünn (Brno) in Mähren, Brünner Kreis, Bezirkmagistrat Brünn, sign. Skř.1-0091.416. Moravian Library in Brno.

k.k. privilegierte Kaiser Ferdinands-Nordbahn was built for steam operation thanks to the money of Salomon Mayer Rothschild in 1836–1856. The last section to Kraków was built at this time. The oldest horse-driven railway on the European continent was in operation between České Budějovice and Linz from 1828.

WIKIPEDIA. 2024. Severní dráha císaře Ferdinanda [online]. Available at: https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Severní_dráha_císaře_Ferdinanda (Accessed: 4 July 2024).

The original single-track viaduct is now hidden in a multi-track embankment.

Constructed as separate buildings because of the different railway companies that operated the railways, the two stations were connected to each other by a common vestibule.

Kuča, K., 2000, p. 97.

The medieval walls from the 13th century were built by the city. The modern Baroque fortifications, however, were financed by the state and therefore came under the administration of the imperial military authorities. See: Hálová-Jahodová, C., 1975, p. 127.

A city is either enclosed or open. An enclosed city is fortified, while an open city is defenceless. An open city is forbidden to attack.

NÁRODNÍ ARCHIV. 2024. 1781, 1. listopad [online]. Available at: https://www.nacr.cz/labyrint/labyrintem-dejin-ceskych-zemi/mezi-absolutismem-a-obcanskou-revoluci/rok-1781 (Accessed: 6 July 2024).

On 1 November 1781, Emperor Joseph II issued a patent that abolished serfdom. This marked a turning point in history, as it freed subjects from personal dependence on superiors and introduced “moderate serfdom.” The patent guaranteed subjects the right to marry, move, and send their children to school without the consent of the authorities.

It is a matter of record that between 1786 and 1829, 600 houses and 14,000 inhabitants were added to the Brno suburbs, while only 20 houses and 3,000 inhabitants were added to the walled city itself. See: Hálová-Jahodová, C., 1975, p. 125.

ŠVÁCHA, Rostislav. 1999. Kapitalismus a kolektivismus v novém československém státě: Praha, Brno a Zlín. In: Blau, E. and Platzer, M. (eds.). Zrození metropole. Moderní architektura a město ve střední Evropě 1890–1937. Prague: Obecní dům, p. 93.

ZATLOUKAL, Pavel. 1997. Brněnská okružní třída. Brno: Památkový ústav v Brně, p. 21.

ESCH, Josef. Project to expand the inner city of Brno, 1845, fond U9, sign. KAT 3. Brno City Archives.

RICHTER, František. 1828–1829. Das Gouvernements Gebäude und der Kiosk am Fröhlicherthor, sign. Skř.1-0091.416. Moravian Library in Brno.

The monastery was dissolved by the decree of Emperor Joseph II of 12 January 1782, and the buildings given to the state, regional, and estate authorities.

Situation eines Teiles des Erweiterungs Projektes der Stadt Brünn, 1845, fond D22, sign. 56 (old 66). Moravian Provincial Archive, Brno.

Zatloukal, P., 1997, p. 52.

The planting of trees on the slopes of Špilberk commenced in the mid-1830s. The mayor of Brno, Christian d’Elvert, is to be credited with the beautification of the Špilberk slopes. See: Nožička, J., 1962, pp. 182–183.

IVANOV, Petr. 2007. Příběhy hradu Špilberku. Bachelor thesis. Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University in Brno, pp. 21–22. Available at: https://is.muni.cz/th/zf7og/Bakalarska_prace_-_Petr_Ivanov.pdf (Accessed: 6 July 2024).

Hálová-Jahodová, C., 1975, pp. 128–129.

The Revolution of 1848, also known as the Spring of Nations, was a series of revolutions across Europe. Although the Czech lands were violently repressed, it abolished robots, created municipal governments and guaranteed other civil liberties. Emperor Ferdinand V abdicated in favour of his young nephew, Franz Joseph I.

The city’s area expanded from 141.4 ha (of which 36.4 ha were within the medieval walls) to 1816 ha. See: Kuča, K., 2000, p. 100.

Šujan, F., 1928, p. 407.

The city fortress in Brno was abolished as early as 1852, compared to 1857 in imperial Vienna, 1866 in Prague, or 1886 in Olomouc.

Hálová-Jahodová, C., 1975, p. 129.

PEŠA, Václav and DŘÍMAL, Jaroslav (eds.). 1973. Dějiny města Brna. 2. díl. Brno: Blok, p. 17.

Kuča, K., 2000, pp. 100–101.

City Plan of Brno, fond U9, sign. KAT 5. Brno City Archives.

The newly created boulevard was later named after Empress Elisabeth of Bavaria, known as Sissi. In 1918, the north-south boulevard changed its name to Husova Street.

SEIFERT, Joseph. Plan to acquire more building sites for the construction of public and private buildings in the inner city of Brno, 1855, fond U9, sign. K 26. Brno City Archives.

The Technical College building is now home to the Faculty of Medicine of Masaryk University (Komenského náměstí 2).

The bastion fortifications were demolished between 1859 and 1864.

SEIFERT, Joseph. Plan to acquire more building sites for the construction of public and private buildings in the inner city of Brno, 1855, fond U9, sign. K 26. Brno City Archives.

Kuča, K., 2000, p. 102.

The designs of the preceding architects, Josef Esch and Joseph Seifert, were no longer applicable due to the necessity for a sealed boundary.

The architect Christian Friedrich Ludwig von Förster had been involved in several projects in Brno since the 1840s. In collaboration with Theophilus Hansen, he was responsible for the design and construction of the Franz Klein City Palace. Additionally, he was the architect of several public buildings (kasino) in Lužánky Park and a new school building (Realschule) on Jánská Street.

HRŮZA, Jiří. 2011. Stavitelé měst. Prague: Agora, pp. 72–73.

FÖRSTER, Ludwig. Project for the extension of the provincial capital of Brno, 1860, fond D22, sign. 367 (old 460). Moravian Provincial Archive, Brno.

Following the administrative expansion of the city in 1850, the municipality was subdivided into four self-governing districts, each with its own committee. These districts were subject to the Brno City Hall, which was represented by a municipal committee. See: Kuča, K., 2000, p. 102.

Kroupa, J. (red.), 2015, p. 59.

Johann. Project to expand the inner city of Brno, 1861, fond U9, sign. K 175. Brno City Archives.

GALETA, Jan. 2020. Výstavba moravských měst (veřejný zájem). In: Vybíral, J. (ed.). Síla i budoucnost jest národu národnost. Prague: UMPRUM, p. 457.

Somewhat unexpectedly, neither Ludwig Förster nor Johann Lorenz, the authors of the two previous regulatory plans, participated in the competition. See: Kuča, K., 2000, p. 106.

The architects submitted six variants (A–F) for consideration in the competition, which differences from one another. See: Zatloukal, P., 1997, p. 58.

KELLNER, Moritz and NEUBAUER, Franz. Varianta F, soutěžní návrh č. 11, 1861, fond U9, sign. K 30. Brno City Archives.

The principal German-language periodicals were the Brünner Zeitung and Neuigkeiten. See: Zatloukal, P., 1997, p. 59.

Zatloukal, P., 1997, p. 59.

NEUBAUER, Franz and collective. Plan of the inner city of Brno and connected suburbs, 1862, fond U9, sign. K 33. Brno City Archives.

Kroupa, J. (red.), 2015, p. 63.

Plans of land intended for regulation and extension of the inner city of Brno from 1863-1877, fond A 1/22, inv. num 3357. Brno City Archives.

At the Exposition Internationale d’Électricité in Paris in 1881, the mayor of the city, Gustav Winterholler, took an interest in Thomas Alva Edison’s innovation – electric light bulbs. See: Zatloukal, P., 1997, p. 104.

The most significant urban planning intervention was the construction of a new street along the Gothic church of St. James, which is now known as Rašínova Street.

Brno, which had previously undergone one administrative enlargement in 1850, was annexed to two towns (Královo Pole and Husovice) and 21 surrounding villages in 1919.

KORYČÁNEK, Rostislav. 2003. Česká architektura v německém Brně: město jako ideální krajina nacionalismu. Brno: ERA, pp. 29–54.

PORTÁL ÚZEMNÍHO PLÁNOVÁNÍ MĚSTA BRNA. 2024. Regulační plán města Brna (1928) [online]. Available at: https://upmb.brno.cz/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/1926.pdf (Accessed: 24 July 2024).

BRNĚNSKÝ ARCHITEKTONICKÝ MANUÁL. 2024. Autobusové nádraží u hotelu Grand. [online]. Available at: https://www.bam.brno.cz/objekt/c158-autobusove-nadrazi-u-hotelu-grand (Accessed: 24 July 2024).

VYBÍRAL, Jindřich. 2002. Česká architektura na prahu moderní doby. Prague: Argo, p. 161.

Galeta, J., 2020, p. 459.

PORTÁL ÚZEMNÍHO PLÁNOVÁNÍ MĚSTA BRNA. 2024. Regulační plán města Brna (1895–1898) [online]. Available at: https://upmb.brno.cz/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/1895_1898_Plan_Brna.pdf (Accessed: 25 July 2024).

JEŘÁBEK, Tomáš et al. 2005. Brněnské paláce: stavby duchovní a světské aristokracie v raném novověku. Brno: Barrister & Principal, pp. 179–187.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2024.58.3-4.7

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License