This study examines the enduring legacy of Eliel Saarinen’s boulevard concept, originally proposed in his 1918 Greater Helsinki Project, and its influence on Helsinki’s urban planning over the past century. Although the boulevard was never realized, Saarinen’s vision was instrumental in the city’s development, setting a precedent for subsequent urban design initiatives. Through analysis of a series of urban plans from the early 20th century to the present, this article traces the sociopolitical dynamics that have continuously redefined Helsinki’s urban landscape. Examining both the realized and the unrealized designs, the study demonstrates how Saarinen’s ideas have been adapted, contested, and ultimately integrated into the city’s spatial organization. The article offers a deeper understanding of Helsinki’s urban planning history, providing insights into the interplay between visionary design and practical implementation in shaping contemporary cities.

Introduction

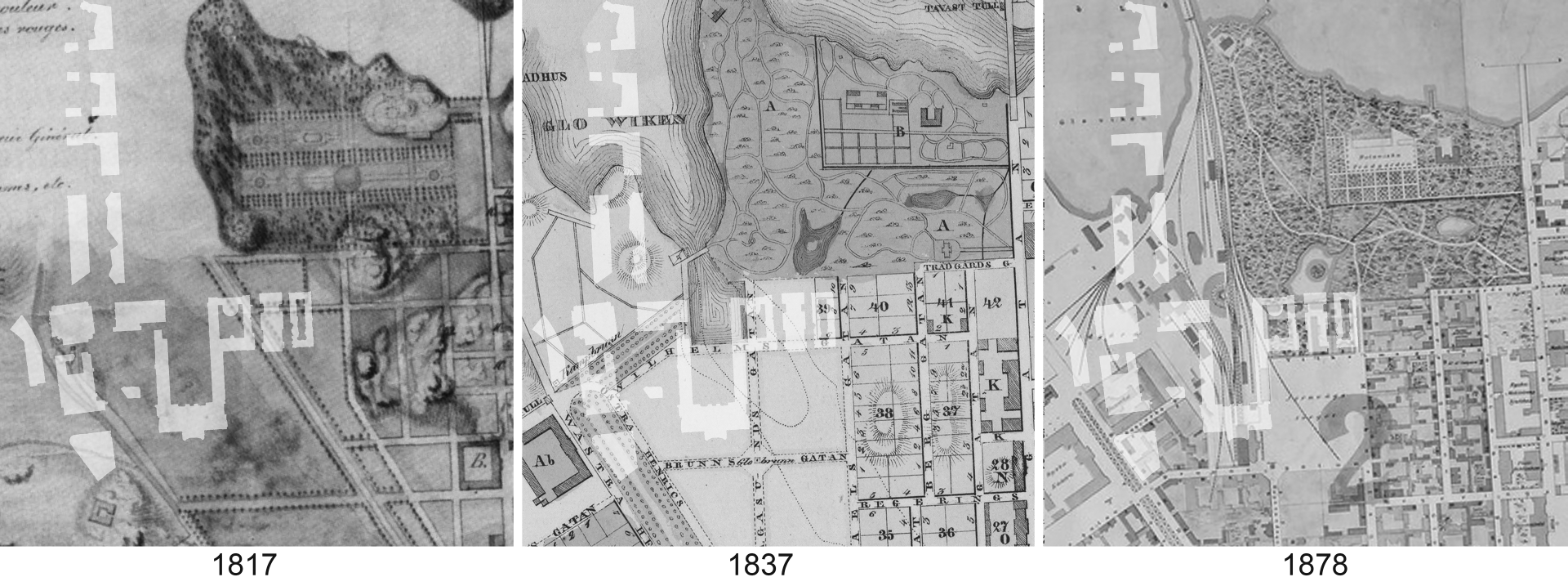

In the European context, Helsinki is a relatively young city, lacking the medieval remnants that characterize many older capitals. It was only following the Swedish defeat in the Finnish War of 1809 that Helsinki replaced Turku in 1812 as the capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland, then still under the Russian Empire. The city’s medieval-style wooden structures and narrow alleys were largely destroyed in a fire, prompting the establishment of a new urban grid plan by Johan Albrecht Ehrenström, which was approved by the Tsar in 1817. This grid laid the foundation for the central area of Helsinki as it exists today. In the second half of the 19th century, Helsinki’s population grew rapidly, transforming it from a modest town into a bustling city and laying the groundwork for its future development.

However, Helsinki’s urban expansion in its central areas was associated with two key factors. First, its position on a peninsula, bordered by water in several directions, left it with only a limited land connection to the northwest. This geographical constraint and restricted space for development significantly influenced Helsinki’s urban planning. Second, the necessity for the railway to extend northward to connect with the rest of Finland made the relationship between the railway and urban space a crucial factor in the city’s expansion. Faced with these dynamics, Finnish architects and urban planners proposed various solutions. Among these, Eliel Saarinen’s Greater Helsinki Project [Pro Helsingfors] stood out as one of the most influential designs, addressing the key issues of geographical limitations and railway integration in shaping the core area of Helsinki.

As a well-known architect of the Romantic Nationalism era that accompanied Finland’s independence after 1917, Saarinen established his reputation in the first decade of the 20th century through a series of successes in domestic projects and international competitions. Saarinen created two master plans for Helsinki: The Munkkiniemi-Haaga Plan (1915) and the Greater Helsinki Project (1918). Both plans comprehensively addressed the entire city and aimed to elevate Helsinki to the status of a metropolis comparable to other major European capitals. In the Greater Helsinki Project, Saarinen proposed a ninety-meter-wide, three-kilometer-long King’s Avenue [Kuningasaveny], a northward-extending boulevard. By integrating tree-lined streets, underground trams, and commercial spaces, this grand boulevard sought to reshape the urban structure and guide the city’s expansion.

Although Saarinen’s grand boulevard was never realized, the concept he introduced has served as a benchmark for urban planning in the decades that followed. The evolution of Helsinki’s urban development has, in many ways, validated the foresight embedded in Saarinen’s proposal. The area originally designated for his boulevard remains a central and strategic part of Helsinki, continuing to hold significant potential for future development. This prominence underscores Saarinen’s foresight regarding the city’s spatial organization and functionality.

The existing literature thoroughly covers Helsinki’s urban planning history, often situating it within a West-East geopolitical context and tracing its evolution from a provincial capital to the capital of an independent nation-state.1 However, this article narrows its focus to a specific aspect of the city’s expansion: the enduring influence of Saarinen’s boulevard concept on Helsinki’s urban planning over the past century. To explore this, the study examines the historical context of Saarinen’s urban plan, the details of his boulevard proposal, and the subsequent efforts by architects such as Oiva Kallio, Pauli Blomstedt, and Alvar Aalto. Additionally, this article examines the sociopolitical changes that have shaped Helsinki’s development, highlighting the shift towards more inclusive urban planning processes. By situating Saarinen’s boulevard concept within the broader narrative of Helsinki’s urban evolution, this study offers insights into how historical planning ideas continue to resonate within contemporary urban landscapes.

The Background for the Greater Helsinki Project

In the early 19th century, the site of the present Central Railway Station – later the starting point for Saarinen’s boulevard proposal – was located on the outskirts of Helsinki, within Kluuvi Bay [Kluuvinlahti], then a swamp and later filled in for the construction of the railway. At that time, the greatest part of the city was concentrated on the Vironniemi peninsula, along the eastern coast of Kluuvi Bay. The old city center was anchored by the combination of Market Square [Kauppatori] and Senate Square [Senaatintori]. The southern shore of Kluuvi Bay marked the boundary of Helsinki, with the northern area yet to appear on the city map.

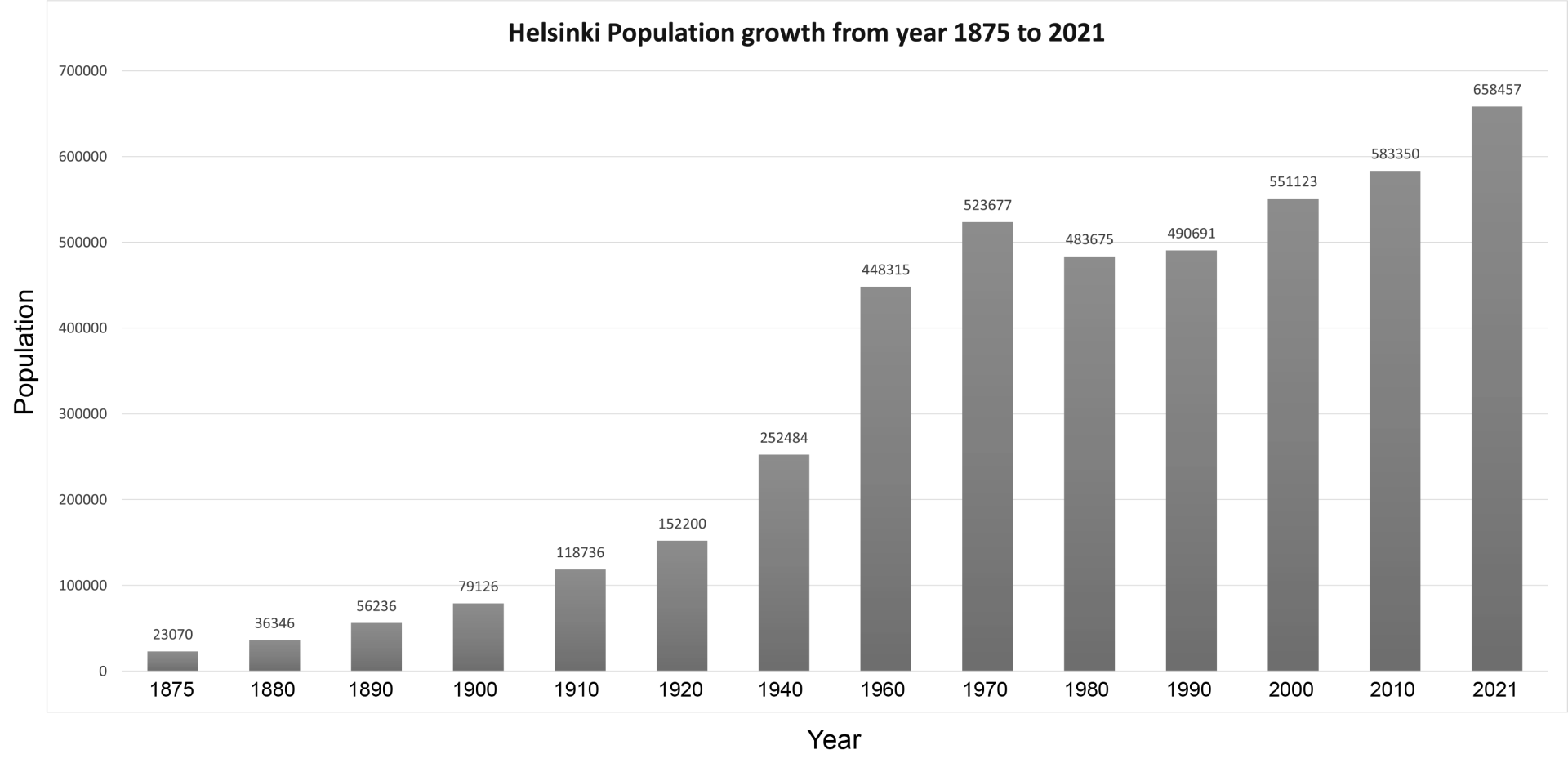

When Helsinki became the capital in 1812, its population grew rapidly.2 In 1880, the city had 36,346 residents, but within two decades, this number had increased to over 79,000. By 1910, the population had exceeded 118,000.3 As the city expanded, there was no longer sufficient space for development within the old town, necessitating the creation of new areas.4 This rapid growth, combined with the emergence of outstanding figures in the design field, propelled Finland’s architectural and artistic development into a golden era at the dawn of the 20th century.

Helsinki’s first railway station, built in 1862 to serve the Helsinki-Hämeenlinna line, soon proved inadequate due to the city’s rapid growth. In response, a new station was proposed in 1895, with Saarinen’s design for the new Helsinki Central Railway Station winning the competition in 1904, marking one of his most significant works. This design not only reflected Saarinen’s distinctive aesthetic style but also played a crucial role in shaping Helsinki’s urban landscape. The construction of the railway and the new terminal building spurred rapid development around the station, attracting new structures and urban activities gathering around the station squares. This transformation established the area as the new city center of Helsinki, symbolizing a “democratic Finland,” while Senate Square, marked by the statue of Emperor Alexander II, continued to reflect the “Russian and imperial” influences.

In addition to his architectural works, Saarinen’s urban planning schemes also had a profound and lasting impact. Although his career in urban planning was relatively brief during his time in Finland, Saarinen developed several influential projects, including master plans for Budapest, Tallinn (Reval), Canberra, and Helsinki.5 Despite his status as a novice architect from the “periphery of Europe” at the time, his work combined Jugendstil with motifs from the Finnish epic Kalevala, crafting a distinctive Romantic Nationalism style. This approach not only resonated within Finland but also served as a significant source of inspiration for other European nations, in particular Estonia and Hungary – both of which had been part of large imperial systems but were striving to establish their own independent national identities.6

In 1911, Bertel Jung crafted the first master plan for Helsinki, setting a foundational vision for the city’s development. However, during its time as part of the Russian Empire, urban planning in Finland was tightly controlled by the imperial authorities. As Finland’s sense of national identity strengthened, the Russification policies imposed by Russia at the turn of the 20th century further intensified the country’s aspiration for independence. When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, Finland seized the moment to declare independence and became a republic. Following independence, authority for urban planning gradually transitioned from a monopolized system to the municipal level, increasingly reflecting public opinion and aligning with modern European practices.7

Despite this shift, municipal support in Finland remained insufficient, fostering a close collaboration between the private sector and urban planning.8 Private companies often commissioned talented architects to design residential areas, and Saarinen was actively involved with these private ventures.9 As a result, his participation was not only driven by his architectural vision but also by financial interests, as he was a shareholder in these companies. The ambitious urban development plans could stimulate the sale of building materials and ultimately generate profits, reflecting the intertwined nature of architecture, commerce, and urban growth during this period.10

The First World War significantly boosted Finland’s foreign trade, with a surge in orders for industrial products from Russia, which indirectly stimulated the expansion of the domestic construction industry. However, this economic boom came to an abrupt halt with the Russian Revolution. Following Finland’s independence, the Finnish Civil War broke out in 1918, further destabilizing the political environment and causing a suspension of construction activities. As architectural design commissions dwindled and the Finnish building industry fell into recession, Saarinen redirected his focus during this period toward urban planning projects.11

After experimenting with his design visions in the Munkkiniemi-Haaga Plan,12 Saarinen, in collaboration with Bertel Jung and Einar Sjöström, developed the Greater Helsinki Project in 1918.13 This urban plan was commissioned by Julius Tallberg, a prominent commercial counselor and business magnate with considerable influence over municipal policies. Tallberg’s proposal to fill Töölö Bay [Töölönlahti] and relocate the Central Railway Station became the central issue that catalyzed the Greater Helsinki Project.14 The plan envisioned new urban blocks constructed on the reclaimed land, with the station relocated three kilometers northward in Pasila, transforming the existing station into a public building surrounded by city squares. This plan for a new urban center and transportation hub laid the groundwork for implementing Saarinen’s boulevard concept.

King’s Avenue: The Boulevard Linking the City Center to the New Railway Station

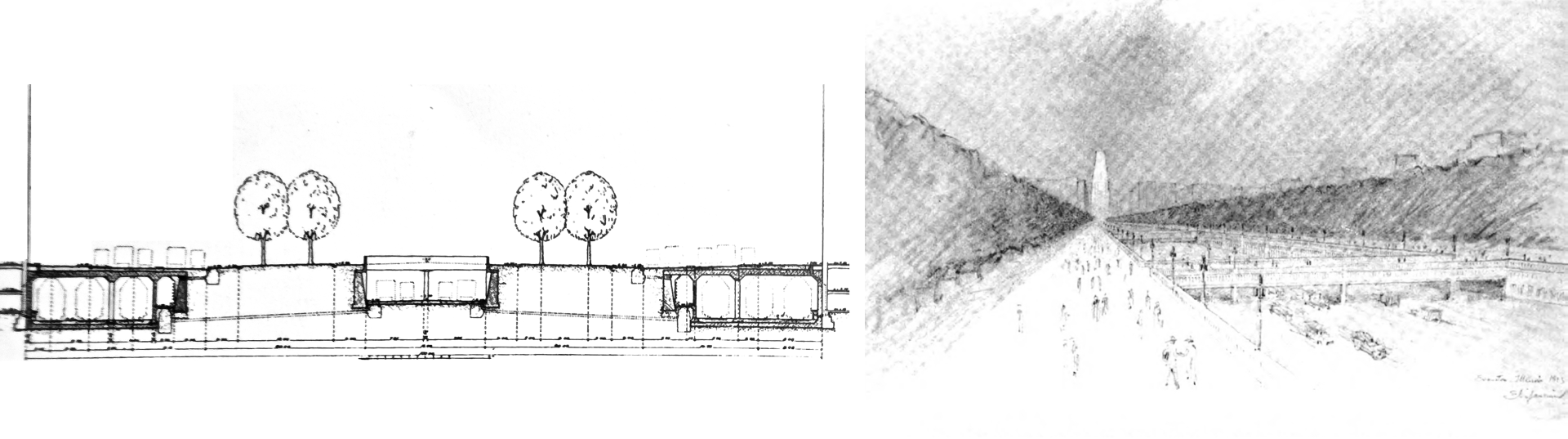

In Saarinen’s vision, a grand boulevard named King’s Avenue [Kuningasaveny] was designed to stretch from the current Central Railway Station to Pasila.15 This boulevard, beginning at the plaza on the station’s west side and extending to the west side of the new Pasila station, would be divided into three lanes and flanked by commercial streets on both sides. Integration of the transportation hub with these commercial spaces resulted in the width of King’s Avenue exceeding over ninety meters. The station’s west wing was slated for demolition, with typical urban blocks featuring courtyards to be constructed on the original railway tracks. The space between the remaining station buildings and new buildings was to be transformed into a garden courtyard.

Saarinen’s experience with the Central Railway Station provided him with a deep understanding of railroad operations and fueled his interest in rail transportation planning. This interest is clearly reflected in the design of the boulevard transportation system within the Greater Helsinki Project, where the boulevard was envisioned as a key transportation hub. In this plan, three of the rail transit lines were placed underground. The central line, which was the city’s tramway, played a vital role in the public transportation network: positioned relatively shallowly, this line remained open to the air above the tracks, with bridges periodically connecting both sides. Flanking the tram line, beneath the roads for car traffic, were commercially operated urban rail lines, with stations accessible through the underground levels of adjacent buildings. Saarinen and Jung viewed this boulevard as a statement of Helsinki’s status as the capital of a newly established, Western-oriented, and rapidly developing state.16

During the design phase of Helsinki’s Central Railway Station, Saarinen had already begun to consider the limitations of its current location with respect to the city’s growth and to explore potential sites for a new station.17 Following his philosophy of decentralized urban planning, Saarinen envisioned two distinct city centers for Helsinki, connected by a major boulevard to ensure the city’s cohesive integrity. The relationship between the newly planned railway station and the old city center was first examined by Saarinen in his 1912 urban planning commentary for Budapest, which can be seen as a precursor to the core concepts of the Greater Helsinki Project.18 Saarinen and Jung argued that the existing space in the city center was insufficient to meet future railway demands. Additionally, the railway yard [Ratapiha] occupied a significant area of land in the city center, effectively splitting the city into two parts.19 Therefore, Saarinen and Jung proposed relocating the train station to free up valuable space, thereby enhancing the connection and continuity of urban areas.

However, Saarinen’s plan faced criticism after its announcement, with the arguments focusing on several key points. First, Saarinen’s plan directed the city’s expansion northward, yet within the Finnish architectural community opinions strongly differed about the ideal direction for Helsinki’s growth. For example, in 1915, architect Valter Thomé already opposed Saarinen’s strategy of extending Helsinki to the northwest. Thomé advocated for latitudinal expansion to the east, proposing a bridge to connect the city to Kulosaari Island. He suggested prioritizing architect Lars Sonck’s 1909 plan, which aimed to develop the entire island of Kulosaari into an “elite” residential area and more effectively respond to Helsinki’s rapidly growing population.20

Second, there were concerns that the new plan would cause the commercial center to shift away from its existing location, leading to excessive fragmentation.21 Critics argued that rather than creating multiple centers as Saarinen envisioned, the plan would effectively relocate the current center northward, relegating the existing urban core to a secondary status. Third, at that time, Helsinki’s main ports were situated relatively close to the Central Railway Station, hence moving the station three kilometers north would complicate the connection between maritime and rail transport. Carolus Lindberg, who later became a professor at the University of Technology in Helsinki, believed that Pasila was too far from the main ports, making it difficult for both ferry passengers and cargo to access the rail system.22

During the early 20th century, Finland’s political landscape was marked by significant uncertainty, both before and after independence.23 In the 1919 Helsinki Municipal Election, for the first time, left-wing individuals with socialist leanings were able to participate in urban planning decisions, challenging the proposals put forth by non-socialists, including those by Saarinen.24 At the time, one of Finland’s most pressing concerns was the need to provide adequate housing for the rapidly expanding working class. In Saarinen and Jung’s vision, however, Helsinki was to become a capital that could rival influential European cities such as Berlin, Paris, St. Petersburg, and Brussels.25 Saarinen’s design of grand boulevards and fine buildings was perceived as catering to the “enlightened bourgeoisie”.26 The inclusion of extensive commercial spaces and large building areas within his expansive boulevard plan suggests an awareness of the economic forces at play, which likely provided financial benefits to Saarinen himself.

Moreover, as modernism spread, Saarinen’s national romanticism came under scrutiny for not aligning with the progressive spirit of the times. Sigurd Frosterus, who secured second place in the Central Railway Station competition, encapsulated this sentiment, stating, “We do not live on hunting and fishing anymore, as in the old days, and decorative plants and bears – to say nothing of other animals – are hardly representative symbols of the age of steam and electricity.”27 This criticism highlighted a broader tension between Jugendstil styles and the emerging modernist ethos.

Tallberg’s death in 1921 abruptly halted the momentum behind the Greater Helsinki Project. Two years later, in 1923, after securing second place in the architectural competition for the Tribune Tower in Chicago, Saarinen emigrated to the United States. Once in the U.S., Saarinen’s involvement in urban planning projects diminished compared to his active role in Europe. However, his concept of a multi-layered boulevard that integrated urban transportation systems resurfaced in his 1923 Lakefront Plan for Chicago.28 In this plan, the central boulevard’s motor vehicle lanes were also designed to be sunken, creating a height difference with the pedestrian paths and tree-lined boulevards on either side, while integrating an extensive underground parking system. Saarinen later encapsulated his planning philosophy in his 1943 book The City: Its Growth, Its Decay, Its Future.29

Evolving Visions:

Urban Plans Shaping the Legacy of Saarinen’s Boulevard

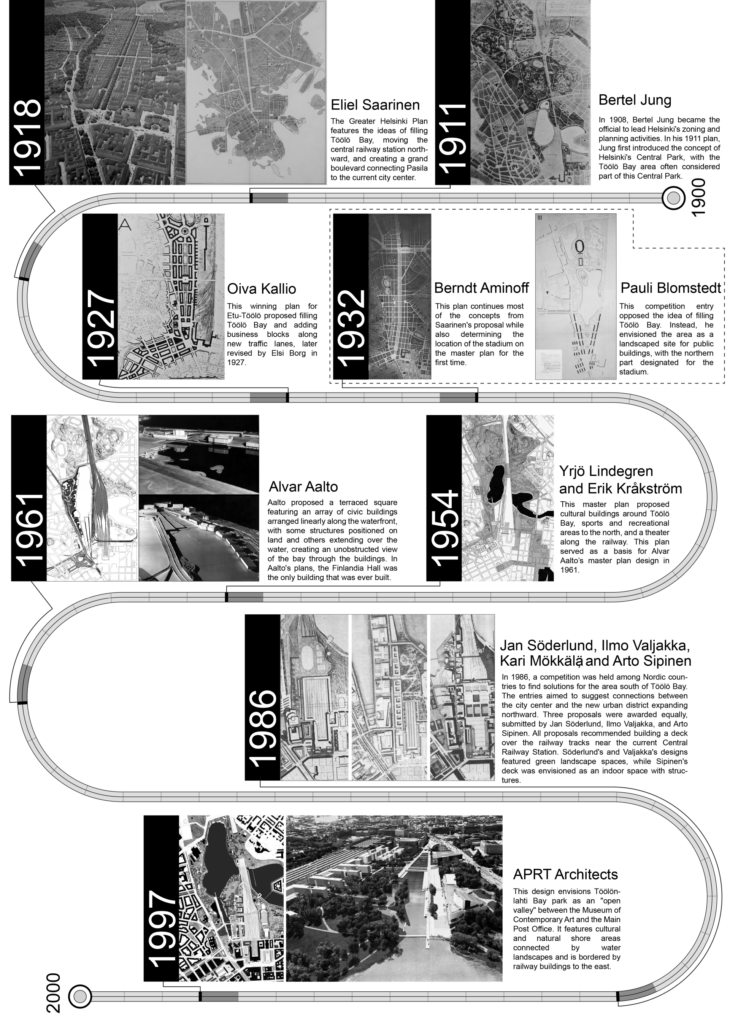

In the decades following Saarinen’s departure from Finland, the area where he had envisioned his grand boulevard became the focus of numerous urban plans. This section explores eleven pivotal planning proposals, presenting them in chronological order and analyzing them within their broader historical and social contexts. These plans illustrate the evolving rationale behind urban design choices, as the initial support for Saarinen’s boulevard concept gradually adapted to changing societal demands and urban dynamics.

Following Saarinen’s introduction of his boulevard concept, the Finnish national railway company strongly opposed his proposal to relocate the existing station. In response, a planning competition for Etu-Töölö, the residential area on the west side of Töölö Bay, was held in 1924. One of the key requirements of the competition was to preserve the station in its original location.30 Oiva Kallio won the master plan competition. As in Saarinen’s plan, Kallio’s proposal included filling Töölö Bay and lining the new traffic lanes with business blocks. In the location of Saarinen’s boulevard, Kallio developed a monumental axis that served as both an administrative center and a business hub, while the station and its surroundings remained separate and intact.

In 1932, town planning architect Berndt Aminoff developed a new master plan that also followed Saarinen’s guidelines. In this plan, the grand boulevard was no longer straight but featured a bend to the north at the Töölö Bay area. The new railway station was once again situated in Pasila, though significantly enlarged and detailed. Additionally, Aminoff determined the location of the Olympic stadium. In a sense, this concept marked the beginning of several public venues built in the following decades along the axis of the envisioned boulevard, even though the boulevard itself was never realized.

Kallio and Aminoff’s designs reflected the evolution in Saarinen’s Greater Helsinki Project roughly a decade after its inception. The emergence of new, prominent public buildings during this period notably influenced the direction of urban planning. A key development was the completion of the Parliament House in 1923, designed by Johan Sigfrid Sirén. This building firmly established the area around the Central Railway Station as the symbolic heart of a democratic Finland, highlighting the importance of preserving open spaces and maintaining the natural landscape around Töölö Bay.31 In response, both Kallio and Aminoff incorporated a parliamentary plaza into their plans. Despite these modifications, the essence of Saarinen’s design remained perceptible. Even after Saarinen had emigrated to the United States, he remained involved as a consultant on Helsinki’s urban planning and expressed strong approval of Aminoff’s approach.32

In 1931, architect Pauli Blomstedt published a compelling three-part series in the Finnish Architects’ Association (SAFA) magazine, Arkkitehti. These articles boldly challenged the prevailing visions of planning authorities and sharply criticized the landfill proposal for Töölö Bay.33 Blomstedt argued that Helsinki could expand in multiple directions rather than the northern development direction shown in Saarinen’s plan. Blomstedt had already anticipated that Helsinki would reach a population of one million, hence the focus of urban development was not on continuously increasing the density of the inner city, but on suburban clusters in the archipelago around Helsinki and along the shoreline.34 With the development of automotive roadways and bridges, Blomstedt believed, Helsinki could expand to the east and west.

Blomstedt’s vision was further articulated in his 1932 master plan for the Olympic Stadium area, which largely overlapped with the site of Saarinen’s boulevard proposal. In contrast to the plans of Kallio and Aminoff, Blomstedt’s proposal marked a shift towards modernism, utilizing free-standing buildings instead of traditional block divisions. He positioned two rows of buildings along the railway and another two rows along Mannerheim Avenue [Mannerheimintie]. As Helsinki prepared to host the 1940 Olympics – ultimately delayed by twelve years due to World War II – the city intensified its efforts to construct sports venues and public recreation spaces, leading to an increased demand for parkland and landscaped areas in its city center.

The completion of the Lauttasaari Island bridge in 1935 was a notable step in Helsinki’s urban expansion. Located on the west side of the city and close to the city center, Lauttasaari gradually evolved into a populated residential area and remains one of Helsinki’s most sought-after neighborhoods. This development contrasts with Saarinen’s original vision for the island, which primarily designated it as a port in his Greater Helsinki Project. Additionally, on the eastern side of the city, the Kulosaari bridge, completed in 1919, connected Helsinki’s main peninsula to Kulosaari Island, further facilitating the city’s expansion. Together, these infrastructural advancements enabled Helsinki to extend its urban footprint both eastward and westward, reshaping the city’s spatial layout.

After World War II, Helsinki’s population almost doubled in 20 years, and several surrounding towns were incorporated into the Helsinki metropolitan area, which increased the city’s size fivefold.35 In 1949, Erik Kråkström and Yrjö Lindegren won the town planning competition for Helsinki’s central area.36 Their proposal, which honored the original terrain, effectively marked the end of Saarinen’s boulevard concept. Instead, the two architects proposed several cultural buildings around Töölö Bay, with sports and recreational areas to the north. Lindegren and Kråkström emphasized the area’s role as a city park, transport hub, and cultural gathering space. Additionally, a site for a possible theater was secured near the railway north of Töölö Bay. The City Theater, later designed by Timo Penttilä and completed in 1967, became the only public building realized from this plan.

Upon his death in 1950, Saarinen was strongly praised by Alvar Aalto. In Saarinen’s eulogy, Aalto remarked, “For the first time, Finland appeared on the continent with tangible, materialized forms as a source of culture that might influence others, rather than simply being on the receiving end.”37 A decade later, in 1961, Aalto was entrusted with the task of designing the urban plan for Helsinki’s core area. However, Aalto’s plan largely built upon the earlier proposals by Kråkström and Lindegren, as he found Saarinen’s grand boulevard concept reminiscent of a “Champs-Élysées in Helsinki,” marked by the archaic aesthetic characteristics of Haussmann’s Parisian architecture.38

Recognizing that the advent of motorized traffic made such a long boulevard impractical in an era dominated by cars, Aalto’s 1961 plan addressed this demand by proposing extensive parking areas and elevated motorways along the existing railway. Aalto also planned a triangular area he called the “Central Open Place,” extending from the Post Office and the square in front of the Parliament towards Töölö Bay. He arranged a series of public buildings along the western edge of this triangular open space and the western shore of Töölö Bay. However, Aalto’s monumental and formalist concepts, along with his revised plans in 1964 and 1972, never received official approval. The only realized element of his master plan was Finlandia Hall, the conference center he had envisioned for the Töölö Bay area. The triangular open place, initially proposed for parking and commercial functions, was eventually realized as a landscaped space.

In 1986, a competition was held again among the Nordic countries to find solutions for the same area. Three proposals were awarded equally, submitted by Jan Söderlund, Ilmo Valjakka, and Arto Sipinen. All proposals recommended building a platform over the railway tracks near the current station. Söderlund and Valjakka’s designs featured green landscape spaces, while Sipinen’s platform was envisioned as an enclosed space with buildings. Like several grandiose master plans before them, these three proposals were never thoroughly studied by the Helsinki planning department.39 Nonetheless, this concept of vertical integration, placing urban public and landscape spaces above the city’s rail lines, once again echoed Saarinen’s boulevard proposal.

As the 20th century drew to a close, APRT Architects won the 1997 master plan competition with a proposal that, like many of its predecessors, sought to reshape the urban landscape along the railway. While Aalto’s 1961 proposed elevating the ground through terracing, APRT Architects chose to lower the terrain, aiming to expand the water surface. Even if the goal of integrating more water into the urban core was not realized, the plan nevertheless led to the development of corporate offices on the western side of the railway tracks. A particularly noteworthy aspect of the plan was its attempt to convert portions of the railway tracks into underground spaces. This vision was exemplified near the Helsinki City Theater, where a landscaped green space, as proposed by the architects, connected both sides of the existing tracks, enhancing the surrounding environment and fostering a more cohesive urban experience.

In summary, none of the plans for the original boulevard location proposed after Saarinen’s Greater Helsinki Project were fully realized. Over time, the urban fabric envisioned for the area evolved, moving away from the rigid grid layout towards a more flexible and free-standing form. Similarly, the function of the area shifted from the commercial hub Saarinen had planned at the start of the century to a space dedicated to culture, sports, and recreation. Throughout this transformation, landscape design emerged as a key element in shaping the area’s development, reflecting a broader trend towards integrating natural elements into urban spaces.

Mapping Transformation:

The Historical Evolution of Saarinen’s Boulevard Area

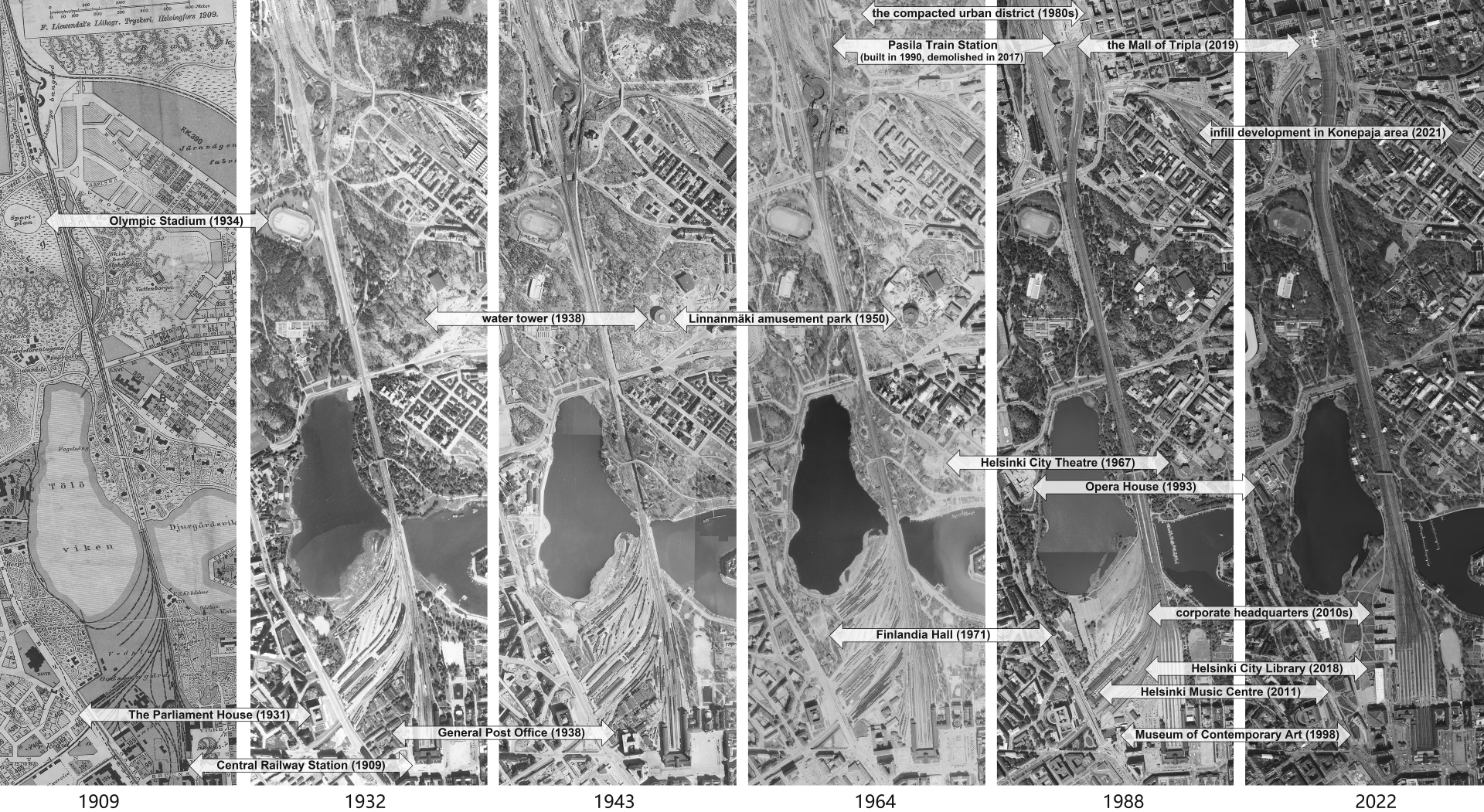

Following the examination of the urban, this section shifts to the empirical evidence provided by the historical map and the aerial orthophotos spanning from 1909 to 2022. These images offer a visual record of the city’s transformation over the past century, allowing us to assess how closely the realized urban landscape aligns with the visionary plans.

Over the decades, the areas initially designated for railway use around the Central Railway Station and Töölö Bay have gradually been repurposed into urban spaces. Since its completion in 1862, the west side of the railway tracks adjacent to the station remained largely inaccessible to the public for over a century, serving primarily as a site for workshops, maintenance, and railway yard operations.40 However, this once-industrial railway yard has been transformed into a vibrant urban space featuring public buildings and landscaped areas. The construction of prominent buildings, including Finlandia Hall (1971), the Museum of Contemporary Art (1998), the Helsinki Music Centre (2011), and the Helsinki Central Library (2018), has added significant public spaces to the area, transforming it into a popular destination for local residents. In a way, this transformation of the railway yard into urban space ultimately fulfills the vision that Saarinen sought to achieve with his boulevard concept in 1918. Additionally, this development in the city center has spurred the northward expansion of scattered buildings along the railway line. Around Töölö Bay, a similar transformation is marked by the construction of several significant public venues, including the Olympic Stadium (1934), the Helsinki City Theater (1965), and the Opera House (1993). The concept of a boulevard endures as an invisible axis connecting these key cultural venues, which strategically capitalize on the open spaces and scenic waterfront views.

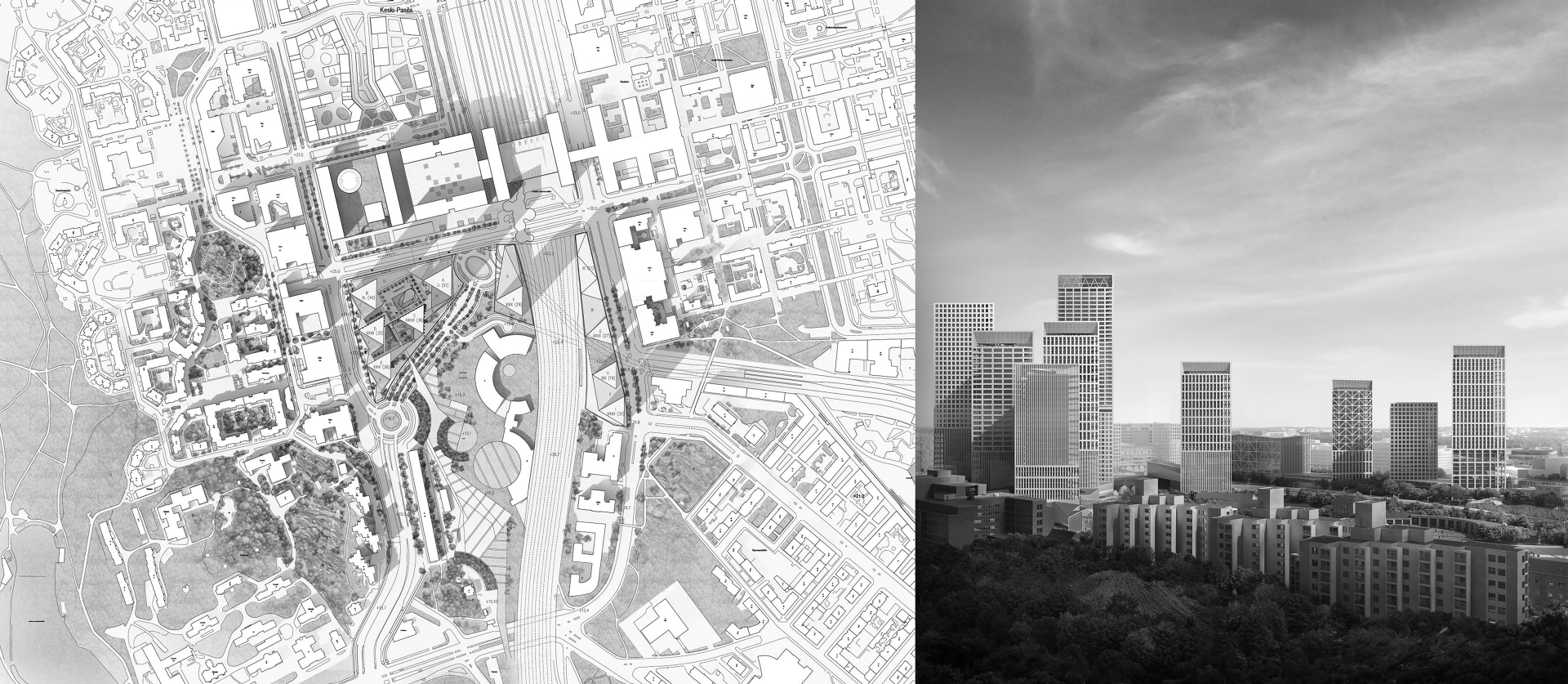

The Pasila area at the northern end of Saarinen’s boulevard has undergone dramatic changes over time. At the beginning of the 20th century, Pasila contained mostly the small wooden station building and was primarily occupied by railway facilities. However, since the 1970s, the area has undergone significant changes. During the 1970s and 1980s, Eastern Pasila [Itä-Pasila] transformed into a high-density, multifunctional urban neighborhood with office, residential, and commercial spaces. The construction of the modern Pasila Railway Station, completed in 1990, further solidified the area’s role in Helsinki’s urban fabric. Throughout the 20th century, Pasila evolved from a peripheral transportation node to a key railway hub with integrated commercial functions.

Vuosaari Harbor, which opened in 2008 at the easternmost end of Helsinki, became the city’s main port, significantly reducing the pressure on the Pasila railway freight operations. The relocation of the railway depot for goods transport to a more northern location freed up land in Pasila, opening substantial opportunities for redevelopment. This newly available space set the stage for a series of major urban development projects in the vicinity of Pasila, spearheaded by the City of Helsinki. Beginning in 2006, the Konepaja area, once home to the railway locomotive sheds, was transformed into residential units, with infill development attracting new urban functions to the site.

In 2014, an ambitious urban plan was unveiled to establish Pasila as Helsinki’s “second center.” Hannu Penttilä, the deputy mayor of Helsinki at the time, remarked that the plan would “open the gate” to realizing Saarinen’s vision from a century earlier.41 The previous station building near the bridge was demolished in 2017, making way for the Tripla complex, which opened in 2019 and became one of the largest buildings in Finland in terms of floor area.42 However, Pasila’s development is far from complete; its significance within Helsinki’s urban framework continues to grow. In 2017, the Finnish Architects’ Association organized a competition that proposed several high-rise towers for the Pasila area, located near where Saarinen’s envisioned boulevard would have ended. Nevertheless, as with many of the urban plans mentioned earlier in this article, questions remain about how many elements of this proposal will ultimately be realized.

Discussion

Saarinen’s boulevard proposal, conceived with a holistic vision for the city, reflects his ambition to transform Helsinki into a modern metropolis, embodying the aspirations of a newly independent nation. This comprehensive approach distinguishes Saarinen’s Greater Helsinki Project from the later plans, which were more narrowly focused and often defined by specific boundaries. While subsequent plans had their own merits, they tended to address partial issues rather than the city in its entirety. Saarinen’s boulevard proposal sought to integrate all the critical elements of the area – important buildings, urban landscapes, transportation hubs, pedestrian spaces, and more – into a cohesive and powerful form as a grand boulevard. However, the course of history did not provide the conditions necessary for Saarinen to realize his vision, leaving these elements in a fragmented state.

Nevertheless, the area has continued to evolve over the past century through successive planning efforts. Key public venues, including a library, art museum, concert hall, conference center, theater, and opera house, have gradually been established, reflecting the ongoing development of the site. Additionally, the reduction of the railway area and the emergence of large commercial complexes in Pasila represent significant changes that align with Saarinen’s original intent. In the early 20th century, Saarinen envisioned Pasila as a commercial hub with spaces lining his grand boulevard. Today, Pasila’s commercial spaces have evolved into a transportation-commercial complex, capitalizing on the high foot traffic generated by the station. This modern adaptation, while diverging from Saarinen’s original concept of boulevard-lined shops, reflects contemporary urban planning’s emphasis on maximizing the utility of transport hubs. The transformation of Pasila illustrates how urban structures adapt over time, balancing visionary plans with the practical demands of development.

The urban plans analyzed in this article also illustrate the challenges of implementing and executing large-scale projects in the core area of Helsinki. Despite the visionary proposals put forth by influential architects such as Saarinen and Aalto, achieving consensus among multiple stakeholders has proven difficult. These challenges often resulted in the realization of only a few specific buildings from the planning proposals, rather than the comprehensive urban-scale developments originally envisioned. This difficulty in executing large-scale plans reflects broader issues within urban planning, where the complexity of navigating public opinion and institutional bureaucracy often impedes progress. As Saarinen himself observed, the combination of entrenched public sentiment and bureaucratic inertia can cause even the most promising designs to “hit the wall.”43

The expectations for the functions of Saarinen’s boulevard area have evolved over time, reflecting broader changes in urban planning priorities. The construction of key buildings and the hosting of the Olympics heightened the importance of preserving the natural landscape of the Töölö Bay area and responding to the growing demand for outdoor recreational spaces. These developments made it increasingly challenging to implement Saarinen’s vision of a boulevard dominated by commercial and residential uses, with its accompanying dense urban neighborhoods. Consequently, more landscape-oriented visions gained favor, focusing on preserving Töölö Bay as a water feature and developing the site into green spaces for leisure and sports. This vision ultimately shaped the area’s development in the ensuing decades, prioritizing nature over extensive urbanization, and eventually led to the creation of a beloved park in the center of Helsinki.

The evolution of these plans reflects broader shifts in Finnish society and changes in social lifestyles. Helsinki has transformed from a city with many manufacturing industries into one dominated by the service industry, with a focus on quality-of-life improvements. This transition is mirrored in the shift from a car-dominated urban environment to one that increasingly values wellbeing and walkability. The development of urban spaces has become more inclusive, addressing the diverse needs of various social groups. These changes underscore a broader trend toward sustainable urban development, where ecological considerations and the enhancement of public spaces are integral to city planning.

Concluding Remarks

Eliel Saarinen’s 1918 Greater Helsinki Project, with its visionary boulevard proposal, stands as a seminal moment in the urban planning history of Finland. His plan, which sought to extend the city center and reposition the railway transport hub, was not merely an urban planning endeavor but a strategic attempt to dictate the trajectory of Helsinki’s future development. Over the ensuing decades, this corridor, stretching from the Central Railway Station through Töölö Bay to Pasila, has been a focal point for numerous urban planning initiatives. While these proposals have varied in their specifics and many have remained unrealized, each has left its mark on the city’s physical landscape, creating a historical cross-section that reflects the evolving priorities and visions of Helsinki’s urban identity.

When we juxtapose historical urban schemes with the current fabric of the city, the enduring influence of Saarinen’s ideas becomes apparent. His strategic positioning of the train station and his vision for the area’s primary buildings and landscape have, in many respects, foreshadowed the region’s contemporary development trends. Although the social and economic shifts of the past century have precluded the full realization of Saarinen’s grand plan, the foresight embedded in his boulevard proposal remains profoundly relevant. The corridor he envisioned, which now forms the city’s “backbone,” continues to serve as a vital axis that shapes the city’s public realm. This thoroughfare, extending from the Central Railway Station to Pasila, has evolved into a dynamic landscape, hosting key cultural institutions and defining the urban experience at the heart of Helsinki. While the spatial reality diverges from Saarinen’s original boulevard proposal, the essence of his vision endures, underscoring the continued importance of this area in Helsinki’s ongoing urban evolution.

This paper was supported by the STU Scientific

Research Initiation Grant (STF24007T).

Yizhou Zhao

orcid: 0009-0009-2283-5408

Cheung Kong School of Art and Design

Shantou University

243, University Road

515063 Shantou

China

1 KOLBE, Laura. 2006. Helsinki: From Provincial to National Centre. In: Gordon, D. (ed.). Planning Twentieth Century Capital Cities. London: Routledge, pp.73–86.

2 KARPPINEN, Emilia. 2018. Collective Expertise behind the Urban Planning of Munkkiniemi and Haaga, Helsinki (c.1915). In: Hochadel, O. and Nieto-Galan, A. (eds.). Urban Histories of Science: Making Knowledge in the City, 1820–1940. New York: Routledge, pp.164–185.

3 HELSINKI REGION INFOSHARE. 2014. The Statistical Yearbook of Helsinki 2013 [online]. Available at: https://hri.fi/data/en_GB/dataset/helsingin-tilastollinen-vuosikirja/resource/4e178f1a-ceef-4cd0-aaa1-35060e529a4e (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

4 ARCHITECT OFFICE R SCHNITZLER, et al. 2020. Environmental History Report on Asema-aukio and Elielinaukio [online]. Available at: https://www.hel.fi/hel2/ksv/liitteet/2020_kaava/6284_1_RHS_Varastomakasiini.pdf (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

5 Although Saarinen and his partners Herman Gesellius and Armas Lindgren had a common office, he basically worked independently on his urban planning projects. Saarinen’s first phase as an urban planner spanned from 1910 to 1918. During this period, he studied the Budapest master plan, created master plans for Canberra and Tallinn, and developed the Munkkiniemi-Haaga district plan in Helsinki, as well as the Greater Helsinki Project. These major urban plans coincided with the design and construction of the Central Railway Station in Helsinki. Following this intensive urban planning period, Saarinen’s next major project was the Chicago Lakefront Plan in the United States, which began in 1923.

6 In 1911, Saarinen was invited by István Bárczy (1866–1943), the mayor of Budapest at that time, to visit the city and meet with Hermann Jansen and other planning experts. Saarinen drew up his commentary on the Budapest master plan in 1912. See: GANTNER, Eszter. 2018. Linking Emerging Cities – Exchange between Helsinki and Budapest at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century. Journal of East Central European Studies, 67(4), pp.507–521.

7 Karppinen, E., 2018, p. 165.

8 NIKULA, Riitta. 1989. 20th Century Urban Design Utopias for the Centre of Helsinki. Architecture & Comportement / Architecture & Behaviour, 5(1), pp. 29–39.

9 Nikula, R., 1989, pp. 30–31.

10 Nikula, R., 1989, pp. 30–31.

11 MIKKOLA, Kirmo. 1990. Eliel Saarinen and Town Planning. In: Hausen, M., Mikkola, K., Amberg, A. and Valto, T. (eds.). Eliel Saarinen Projects 1896–1923. Helsinki: Otava, pp. 187–220.

12 The primary purpose of the Munkkiniemi-Haaga Plan was to create a new urban district, but its significance lay in how it foreshadowed Saarinen’s vision for the entire metropolitan area. The plan reflected Saarinen’s concepts of decentralized planning, demonstrating his forward-thinking approach to urban development and articulating his vision for the metropolitan area’s growth. See: Nikula, R., 1989, p. 30.

13 JUNG, Bertel and SAARINEN, Eliel. 1918. Pro Helsingfors: Suur-Helsingin Asemakaavaehdotus. Available at: https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/134917 (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

14 Jung, B. and Saarinen, E., 1918, pp. 4–7.

15 Several months later, the Finnish parliament ratified a new constitution establishing Finland as a republic, leading to its name being changed to Nation Street (Valtakunnankatu).

16 Nikula, R., 1989, pp. 30–34.

17 Mikkola, K., 1990, p. 214.

18 Mikkola, K., 1990, p. 196.

19 Jung, B. and Saarinen, E., 1918, p. 12.

20 Mikkola, K., 1990, p. 204.

21 Mikkola, K., 1990, p. 216.

22 Carolus Lindberg (1889–1955) was a distinguished Finnish architect and academic, known for his expertise in town planning and his doctoral dissertation on medieval church restoration. See: LINDBERG, Carolus. 1918. Pro Helsingfors, Arkkitehti, pp. 33–39.

23 KOLBE, Laura. 2016. In the aftermath of Civil War in Helsinki 1918: Eliel Saarinen’s Pro Helsingfors – General Plan and “Fantasizing” the Great City. In: Meller, H. and Porfyriou, H. (eds.). Planting New Towns in Europe in the Interwar Years: Experiments and Dreams for Future Societies. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 145–177.

24 Kolbe, L., 2016, pp. 146–147.

25 Nikula, R., 1990, p. 32.

26 Mikkola, K., 1990,

pp. 218–220.

27 FROSTERUS, Sigurd. 2000. Architecture: a challenge to our opponents by Gustaf Strengell and Sigurd Frosterus. In: Norri, M., Standertskjöld, E. and Wang, W. (eds.). 20th-century Architecture: Finland. Helsinki: Museum of Finnish Architecture / Frankfurt am Main: Deutsches Architektur-Museum, p.125. (The original text “Arkitektur en stridskrift våra motståndare tillägnad af Gustaf Strengell och Sigurd Frosterus” was published in the newspapers Hufvudstadsbladet and Helsingfors-Posten in 1904).

28 SAARINEN, Eliel. 1923. Project for Lake Front Development of the City of Chicago. American Architect – The Architectural Review, 124, 5 December, pp. 487–514.

29 SAARINEN, Eliel. 1943. The City: Its Growth, Its Decay, Its Future. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corp.

30 Kolbe, L., 2006, p. 164.

31 TÖRMÄ, Ilkka. 2020. The Monumental Alliance of Finnish Government and Civilization. Arkkitehti, (5), pp.16–23.

32 VESIKANSA, Kristo and BERGER, Laura. 2024. The Olympic gap: planning and politics of the Helsinki Olympics. Planning Perspectives, 39(3), pp. 501–530. doi:10.1080/02665433.2024.2340639

33 BLOMSTEDT, Pauli. 1932a. Helsingin tulevaisuus I. Arkkitehti, (4), pp. 49–55; BLOMSTEDT, Pauli. 1932b. Helsingin tulevaisuus II. Arkkitehti, (9), pp.134–137; BLOMSTEDT, Pauli. 1932c. Helsingin tulevaisuus III. Arkkitehti, (11), pp.163–169.

34 Blomstedt, P.,1932a, 1932b, 1932c.

35 Kolbe, L., 2006, pp. 169–170.

36 After Lindegren’s death in 1952, Kråkström completed the plan.

37 AALTO, Alvar. 1997. Eliel Saarinen. In: Schildt, G. (ed.). Alvar Aalto in His Own Words. Helsinki: Otava, pp. 243–246.

38 AALTO, Alvar. 1961. Helsingin Kaupungin Uusi Keskusta. Arkkitehti, (3), pp. 33–44.

39 MUROLE, Pentti. 2013. Töölönlahti kierroksessa: osa 3. Pentti Murole blogi [online]. Available at: https://penttimurole.blogspot.com/2013/07/toolonmlahti-kierroksessa-osa-3.html (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

40 Architect Office R Schnitzler, et al., 2020, pp. 20–22.

41 CITY OF HELSINKI. 2013. Pasila: A Second Center for the City [online]. Available at: https://www.hel.fi/static/liitteet/kanslia/helsinki-info/arkisto/2013/Supplement/4_13/pasila.html (Accessed: 15 August 2024).

42 SAVELA, Mika. 2020. Interview: The Many Makers of a Monument. Arkkitehti, (5), pp. 62–79.

43 Mikkola, K., 1990, p. 217.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.6

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License