The aim of this paper is to provide a comprehensive view of the development of ring boulevards in Košice, to relate their emergence to the expansion of urban planning in the broader European region, and to explain why these boulevards do not fulfill the functions held by ring streets in the cities that served as models for Košice. The topic of the ring boulevard and the growth of the city of Košice has already been addressed by several authors in the past, who primarily focused on the social and political conditions of the creation of ring boulevards1. While their sociological perspective on the topic is undoubtedly significant, the present text, by contrast, focuses more on research from the perspective of urban planning and architecture, emphasizing the role of the often obscure local builders whose contributions remain overshadowed by the works of well-known architects. And yet it was precisely these builders who determined the character of the city at the turn of the century. The text of this article is primarily based on the author’s current research and findings acquired in connection with their dissertation.

Introduction

The second half of the 19th century was a period of unprecedented growth in all areas of life in the Habsburg empire: first in the neo-absolutist period from 1849 to 1867, then even more so after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise. It was a long period of peace and an incomparably more dynamic development of all sectors of the economy than ever before. The differences between the Austrian and Hungarian sections of the Dual Monarchy began to level out, and the Kingdom of Hungary became competitive on a global scale. Along with the development of the economy, science, culture, and more, society also changed. Feudal conditions gradually disappeared, and a modern civil society of the type we know today began to develop. Additionally, demographic growth accelerated. The population of Hungary grew from 13.2 million in 1870 to 20.9 million by 19102. Population growth and the concentration of industry in cities accelerated urbanisation processes.

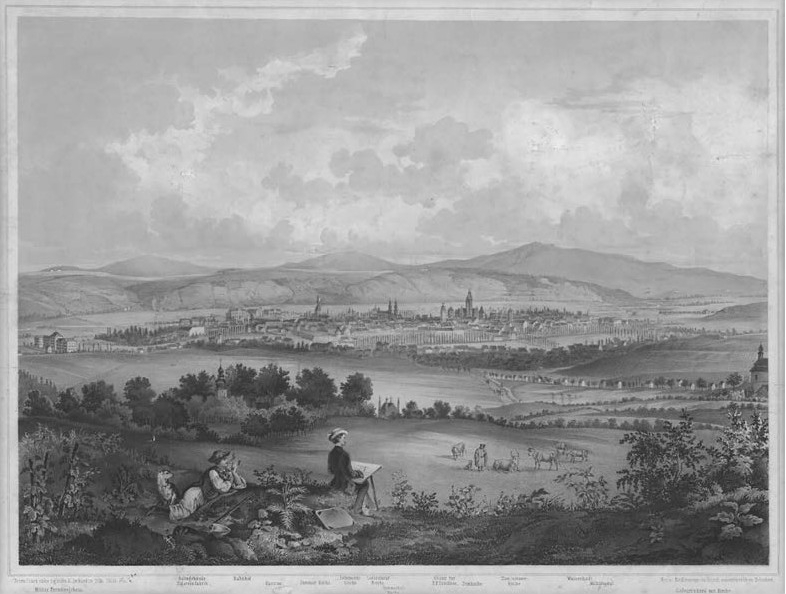

This development did not bypass one of the most significant cities in the country – Košice; indeed, the Gründerzeit period essentially shaped the central part of the city as we perceive it today. The population of Košice grew from 13,700 in 1846 to 44,200 in 19103, a 3.2-fold increase. Košice was connected to the rail network,

and capital both foreign and domestic stimulated industrial development. Funding from the state and the city furthered the opportunities for culture, education, and healthcare. No less, building activities were intensive, and the city expanded.

In political terms, matching the dual structure of the Habsburg state, Vienna’s influence weakened, and Budapest, a rapidly developing capital city competing with Vienna, came to the forefront.

In 2013, the East Slovak Museum and the Budapest History Museum organised a joint exhibition titled “Parallel Histories”4 in Košice. The extensive material convincingly demonstrated the parallels between Budapest, as the capital setting the trends of development, and Košice as a regional centre. Practically, Košice reflected all the leading trends in society, architecture, urbanism, and culture then emerging in Budapest. Of course, the economic conditions in Košice were more limited, and therefore the ring roads modelled on Budapest’s impressive körút boulevards, along with the city’s architecture, green spaces, and the resulting social life in them, are simpler and less developed.

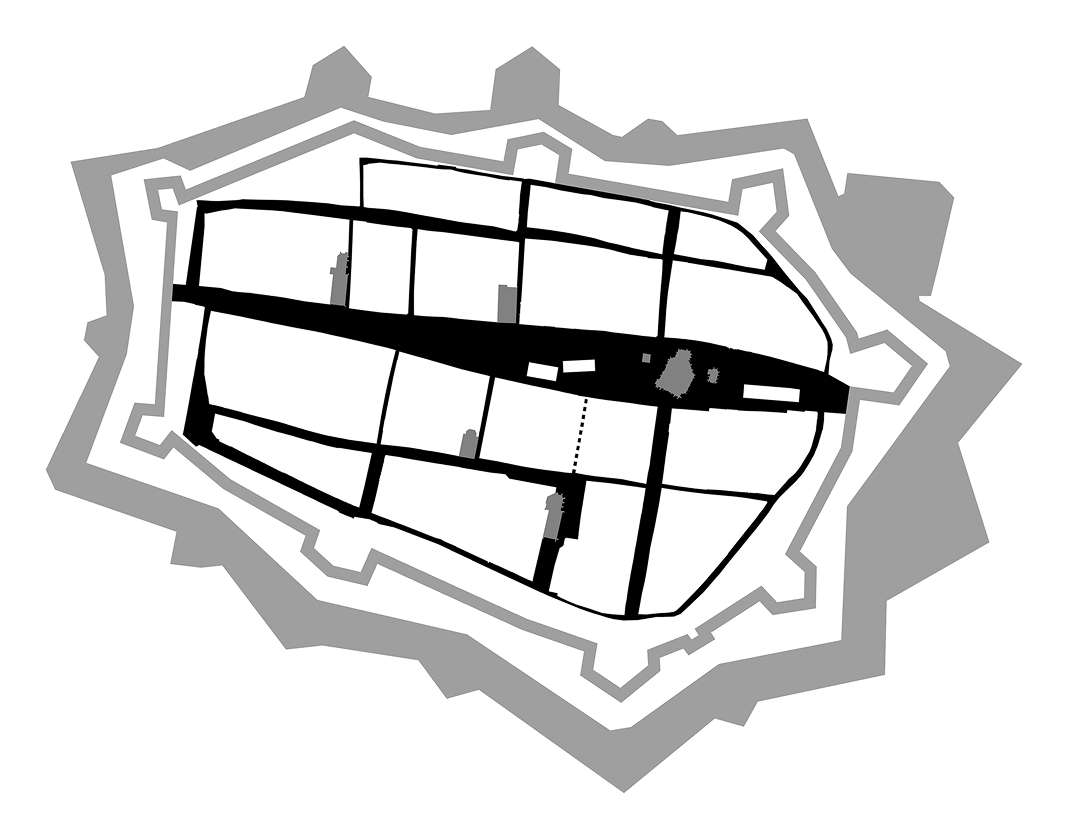

The conditions for the creation of a ring road were set by Košice’s earlier history as a powerful anti-Turkish fortress. During the 150 years of Turkish occupation of the central area of Hungary, even the northern parts of the traditional Hungarian kingdom, under Habsburg rule, were open to military threat. Košice lay in the contact zone, which stretched roughly just above today’s Slovak-Hungarian border. It was here that the Habsburg rulers built a line of fortifications to counter further Ottoman expansion, in a program that involved strengthening existing medieval fortresses, reinforcing existing city walls, and raising new modern fortresses or new fortified towns such as Leopoldov and Nové Zámky. During this time, Košice gained new modern bastion-type fortifications around its entire perimeter, surrounding the existing medieval fortifications. Later, the fortifications were strengthened even further with the construction of a new star-shaped citadel below the southern gate. The three most significant anti-Turkish strongholds in this region were Komárno – Nové Zámky / Leopoldov and Košice, yet the last-named town was never attacked by Ottoman forces.

After the Turkish threat passed, the walls gradually began to deteriorate, and the city started to expand into areas beyond the walls. Occurring in several phases, this development emerged at the end of the 18th century, once the fortifications had lost their military significance. In 1783, Austrian military authorities abolished the status of “Festung Kaschau,” a move that opened the possibility for the gradual dismantling of the once-modern bastion-type fortifications to allow the city to expand. The first step was to break a new gate through them at the end of Alžbetina Street to connect the city with the western glacis.5 While the fortifications of Košice still stood, with the suburbs separated by the glacis, the city’s layout closely resembled that of Vienna. By the beginning of the 1840s, the fortifications had almost entirely been dismantled. This period formed the first phase of development, which also created new street connections to the glacis and further into the suburbs by breaking through the old fortification structures, followed by the modification of the glacis, the razing of earthworks and levelling of ditches, the regulation of various watercourses, and the planting of trees. However, the area of the glacis remained undeveloped at that time The final phase involved construction development within the glacis and the creation of ring roads. However, the city’s spatial growth remained directed not outward into the countryside but, by contrast, inward into the open glacis that surrounded the fortifications, with the outer suburbs of medieval origin lying beyond it.

Košice had ideal conditions for the creation of a ring road around the demolished fortifications. With their oval perimeter, the outline of the fortifications naturally lent itself to the creation of a ring. Moreover, the city was situated on the ideal flat terrain of the Hornád floodplain, bordered to the eastern side with a marshy area of water-meadows and side tributaries of the Hornád.

Planning the Ring Roads

The Premodern Era – Squaring the Circle

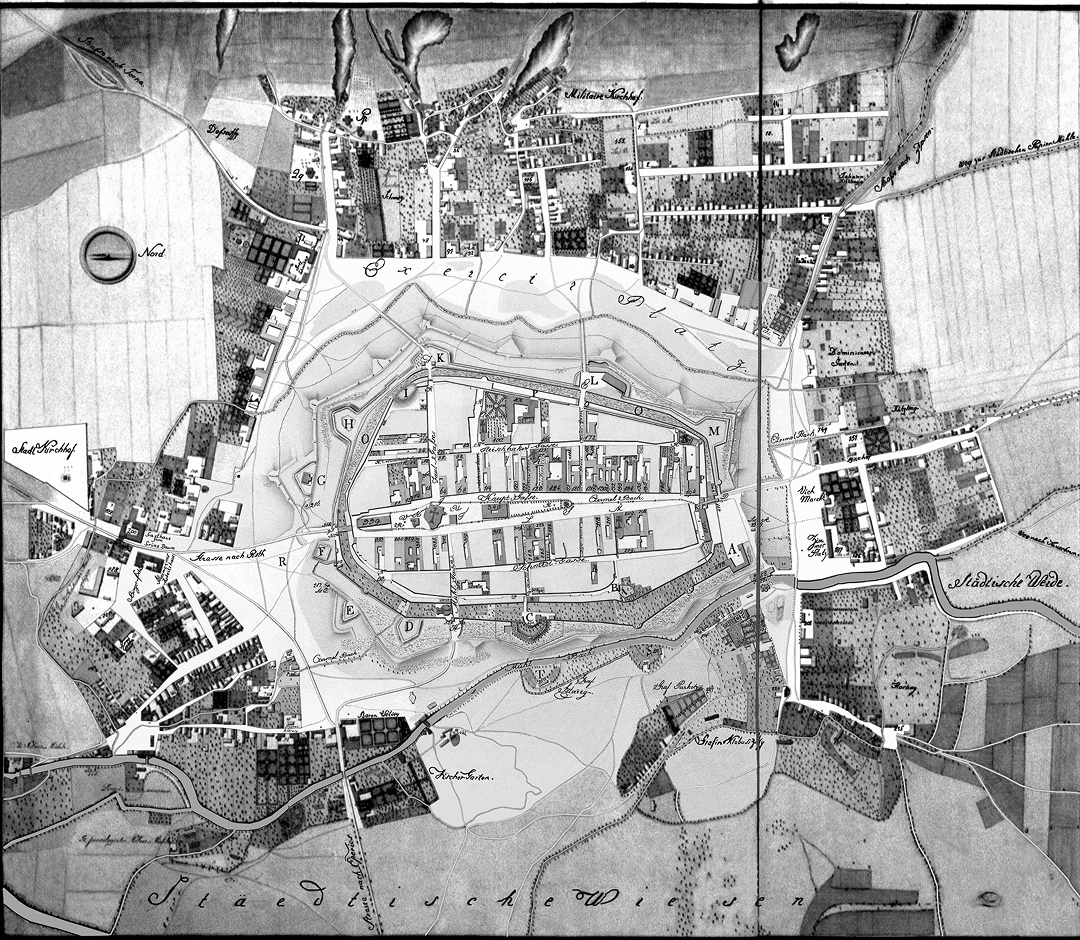

Košice entered the 19th century with its fortifications still standing, albeit now unnecessary, and moreover significantly dilapidated and partially demolished. Surrounding them was an undeveloped glacis, with the suburbs spreading beyond it. However, the city itself still extended only to the line of the fortifications. On the Chunert plan of Košice6, we see the state of the city in 1807. The basic street network of the suburbs, apart from the eastern ones, was already established and, particularly in the west, remained largely unchanged until the second half of the 20th century. On the eastern side, interlaced with branches of the Hornád river and marshy areas, lay mainly meadows and gardens.

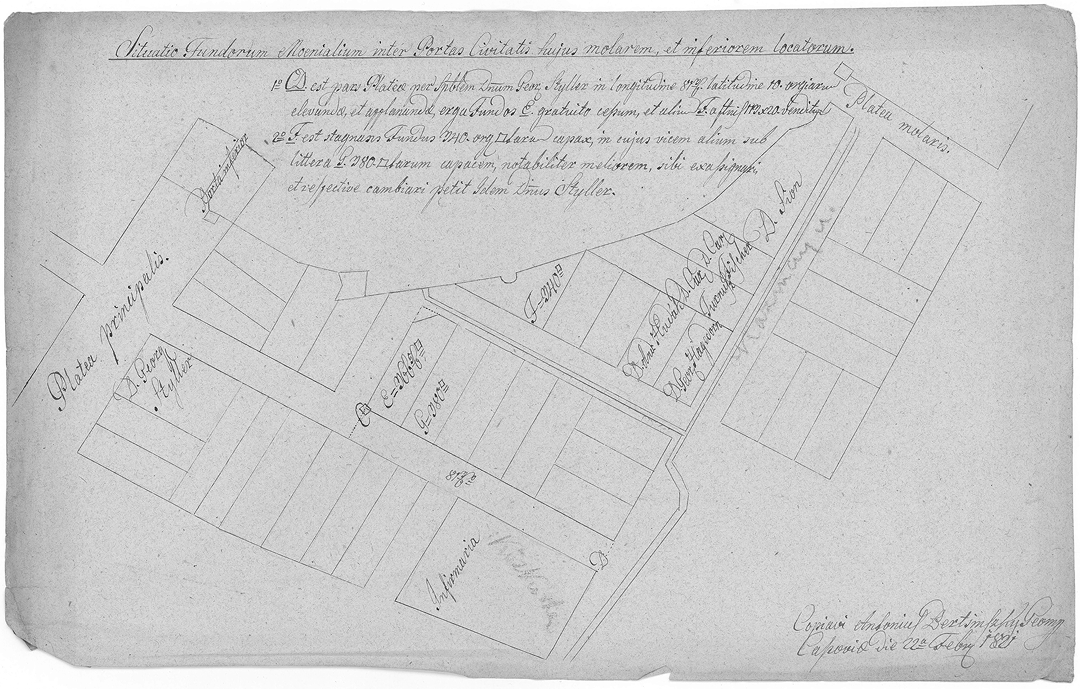

In the so-called Ott plan of Košice7 from 1832, we observe that in the intervening quarter-century, most of the fortifications, including the earthworks and moats, had disappeared. However, the city had not expanded significantly in area. A few new streets were laid out in the first and second quarters, linking the old town to the western glacis, yet with only modest development in that area. Notably, Ott’s plan also depicts a proposal for development of the western glacis: outlining today’s Moyzesova Street, connecting the northern and southern glacis, and suggests its subdivision with streets extending from the old town in a rectangular grid. On the western side of the new street, generous space is reserved for Plätze zu projectirten Gebäuden [sites for projected buildings], with open areas behind them.

The plan ignores the oval shape of the medieval town and straightens it to form a direct, 1.1 km-long avenue. The orthogonal arrangement is a significant design element, as this method of street layout and subsequent parcelling was later applied to extensive areas of development. Ultimately, this led to the circular route being arranged in an orthogonal formation along its entire length. Ott’s plan of Košice is the oldest known document regulating such a large area of the city.

Expanding an oval-shaped city with an orthogonal grid layout may appear a questionable choice. However, if we examine the city’s layout, we see that the orthogonal system within the city’s perimeter was already established in the Middle Ages, formed by the intersection of two streets at the site of St. Elizabeth’s Cathedral, two other streets running in parallel, and several short interconnecting streets at right angles to the main street. Hence, within the oval perimeter of the city, we do not find an organic network of randomly arranged plots, blocks, and streets, organized in the manner of a clustered village – Haufendorf – as in e.g. Nördlingen in Bavaria, nor in concentric circles as e.g. in Eguisheim in Alsace. Consistently, medieval Košice was arranged as an orthogonal grid bounded by an oval perimeter of walls.

Along the inner side of the fortifications, narrow streets emerged, containing the houses of the less affluent citizens. These curved streets, with their houses built directly adjoining the fortification wall, appear less systematic compared to the strictly orthogonal layout of the city.

Today, it is impossible to state definitively why Ott chose a straight avenue and an orthogonal street network. He could have opted for a different solution, such as developing the city in a radial-circular system. However, the major Austro-Hungarian examples of circular systems, such as Vienna’s Ringstrasse or Budapest’s Nagykörút, only emerged decades later, nor he could have been unaware of Europe’s most salient example of orthogonal-grid urban expansion – Barcelona. However, older examples from the late 18th and early 19th centuries did exist. Early instances of city expansion on an orthogonal grid system date to the Baroque period, such as Mannheim and Berlin-Friedrichstadt. And other early examples of circular routes replacing demolished city walls include the Promenadenring in Leipzig. Interestingly, the original name of Moyzesova Street was Sétány [Hungarian: promenade], while many circular routes themselves spontaneously developed around fortifications, such as the Kiskörút [Small Boulevard] in Pest. As such, it is most likely that Ott took his influence from patterns within the German-speaking region.

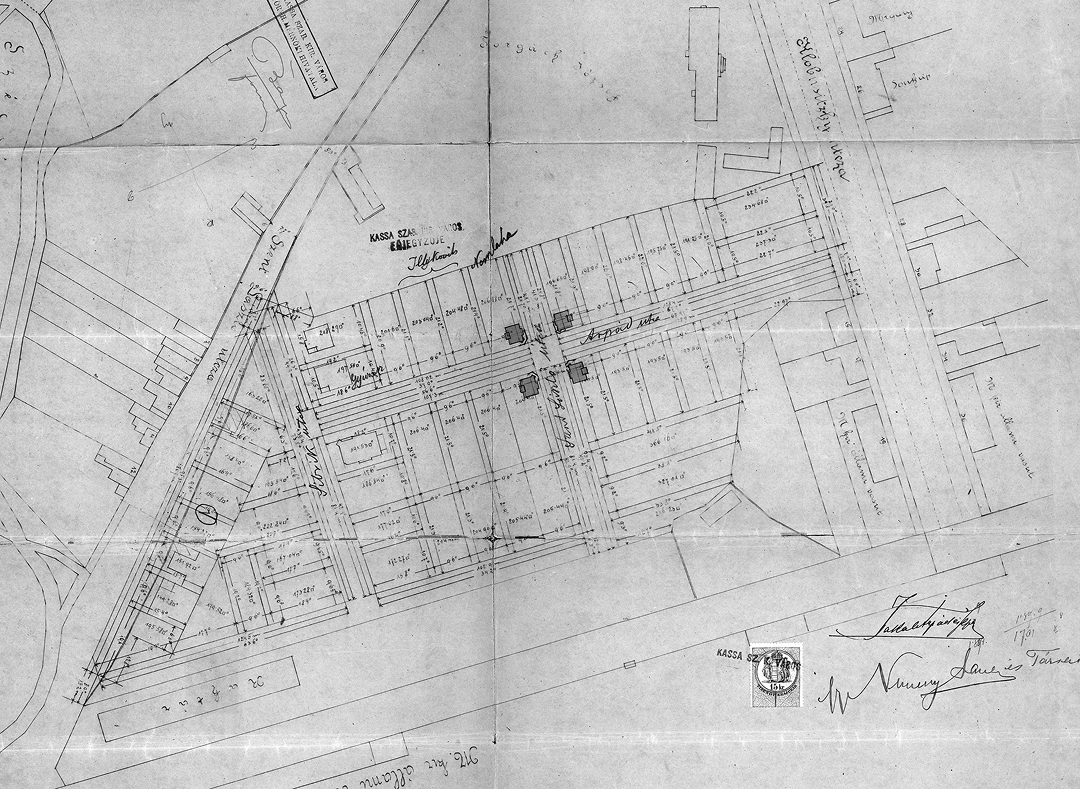

The effort to expand the city along an orthogonal grid of new streets can be discerned as it emerges in all directions outward from the medieval town. In addition to Ott’s plan, this tendency is confirmed by other contemporary documents of urban planning regulation, long unknown until recently: e.g., the proposals for new streets and parcelling on the fortifications site, prepared by Antonius Bertsinszky, and parcelling plans for development areas made accessible by the ring road.

In the end, it remains unclear whether the circular route was the result of a deliberate long-term effort – or, more likely, the outcome of many successive, interconnected decisions, without the route being planned as a single entity.

The Era of Modernization

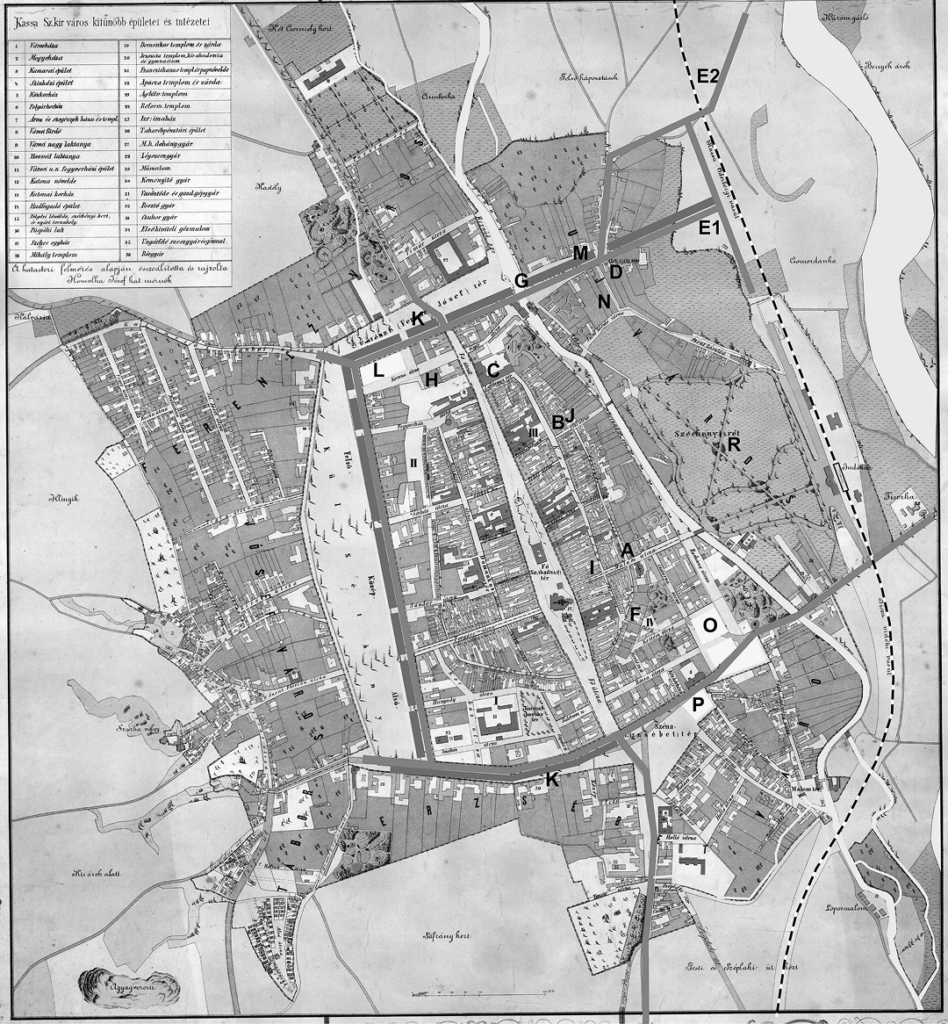

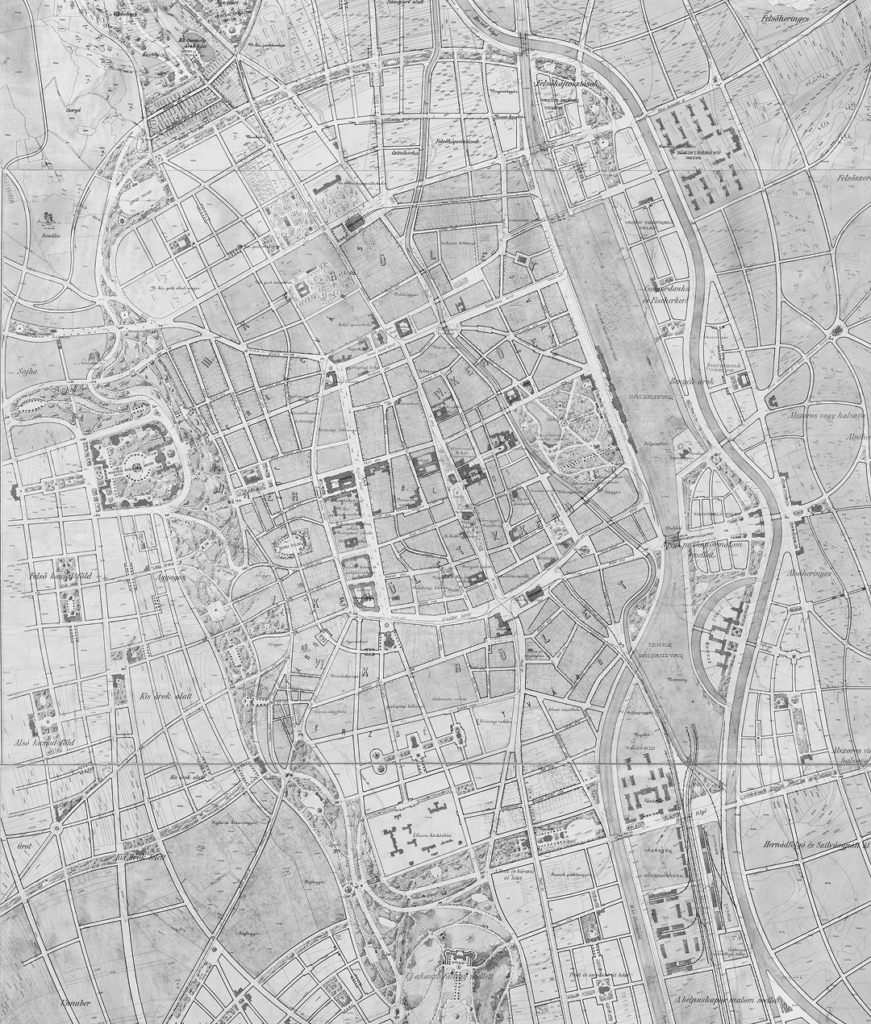

The only evidence from the 19th century supporting the existence of a deliberate effort to regulate the city as a whole or to create a strategic urban plan is the course of action taken by the city administration in 1869, when it set up a commission to identify the urban problems of long-term development, describe them, and propose solutions. The importance of this task is underscored by its being headed directly by the officiating mayor, Gyula Éder; the names of the other members have yet to be uncovered. In the conclusions of the commission’s work, published in 18708, various aspects of urban development were addressed, yet the general conclusion was the urgency of adopting a building code and prepare a regulatory plan. While the building code was completed within four years, the regulatory plan was not forthcoming for another half-century. Here, we will focus only on those proposals of the commission that concern the use of circular outer roadways. The text refers to the attached drawings: though the originals have not survived, the graphics can be reconstructed based on their relatively precise description using the Homolka plan of Košice.9

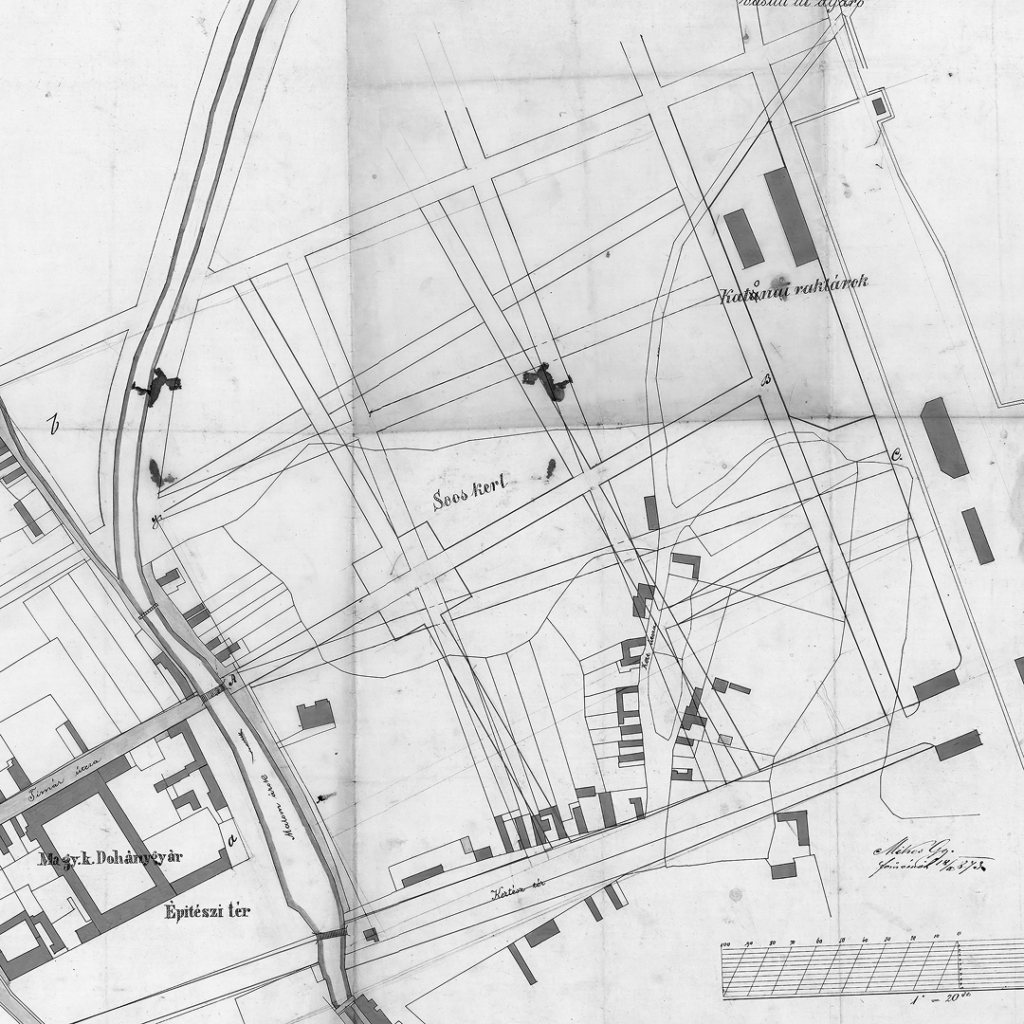

The solutions the commission proposed were indeed ambitious. By the time the commission began its work, a four-row tree avenue already existed along the entire western outer promenade. On the eastern side, there was a well-dimensioned carriageway, while on the western side of the avenue, the Čermeľ stream flowed through a newly straightened channel. Further to the west were additional areas for future development. This arrangement was in line with Ott’s long-extant plan; what the commission now proposed was to extend this urban situation to the northern and southern outer promenades. The northern one was to be created by transforming the square in front of the northern gate into a street (K) and extending it to the railway. This ambition involved breaking through the so-called Mouse Corner (M) and subsequently leaving the railway warehouses and the area of Újváros [New Town] open for development. With this project, the northern segment of the ring road was created – today’s Masarykova Street, which in turn made extensive areas available for new construction.

In the future southern segment, the situation was different. For today’s Štúrova Street, then the national roadway from Budapest to Dukla; the commission proposed development with public buildings and the creation of a unified street profile with a row of trees and a promenade, paralleling the western and northern sides. The unified profile of the space would begin with a 1-fathom-wide sidewalk on the side adjacent to the city, next to a 9-fathom-wide paved roadway, and then a 10-fathom-wide avenue formed by four rows of trees. In the remaining space behind the avenue, there would be room for new construction, markets, and so on. The commission described their proposal as follows: “Apart from beauty, promenades have other advantages; all modern cities of our time have realized their favourable impact on public health and strive to equip their spaces with vegetation. Our outer promenades meet this goal, and therefore we propose that they be extended to the northern and southern parts of the city, so that, as if embracing the city centre, they create a pleasant place for walks around it.”

In this way, the old town would be surrounded by a green ring, with a large city park to be integrated into it. Nor would the circle lack a water element, with the inclusion of the Čermeľ stream (K) and the Mlynský náhon [Millrace]. As such, the commission’s proposal of a ring road would both transportation and the health of the city, while the promenade also enhanced the social life of the city. It is surprising that the term “körút” [ring road] does not appear even once in the entire text. Instead, the term “sétány” [promenade] is consistently used. At that time, Košice already had two promenades on Hlavná [Main] Street – above and below the Cathedral.

The period concludes with the approval of a new regulatory city plan. The first regulatory plan for Košice, it emerged from a nationwide competition held in 1917, while the winning team of architects, László Warga and Jenö Lechner, submitted their preliminary plan to the city7 in the summer of 1921, based on the jury’s comments. Without specifying strictly functional areas, the plan simply identified various spatial types of buildings without functional specifics, industrial and railway areas, and the locations of significant public institutions. This plan confirmed the existing route of the ring road and highlighted its presence in the city by proposing its completion and modifications. Most notable among the interventions was the removal of the barracks from Moyzesova Street and its vicinity, replaced by dense, compact development. The proposed public building at the site of the riding school created a small square at the bend of the ring, while the site of the hippodrome was proposed for a new building for the Festivity Hall with a new post office nearby. To the south, judicial buildings were proposed at the site of the sports facility, and a church was to be placed at the southern end of the axis of Moyzesova Street to mark the street’s dignified end. Interventions also extended to the southeast sector of the ring, where a reconstruction was proposed of Elisabeth Square. Instead of the open market space, a covered market was proposed, and the connection between Masarykova Street and the southern sector of the ring was to be expanded to close the entire ring system. Here, the unattractive section of railway warehouses would be aesthetically balanced with the rest of the ring by constructing a new railway station aligned with the park axis and establishing a new park entrance opposite.

The new plan did not radically alter the ring, already mostly completed. However, from the perspective of emphasizing its ring-structure, the creation of a prominent transverse axis leading from the western slopes of Terasa across the medieval town to the new station is counterproductive. This axis was to be formed by widening the narrow medieval streets Poštová and Biela and breaking through a new street, thereby adding new spaces at the expense of historic streets, which detracts attractive buildings from the ring. Continuing the old trend of turning curved streets into straight ones, the closure of the outlets of Vrátna and Zvonárska Streets into Hlavná Street can be seen as a step that deprives the Old Town of its “inner ring” along the inner side of the medieval fortification line. Going still further, an additional outer ring was introduced, which, besides transportation, also served as a green belt around the city. To the north, a wide communication route with a massive green belt connected the Hornád River waterfront and the slopes under today’s Terasa housing estate to a proposed large park on Šibena hora [Gallows hill], and from there, it turned back to the Hornád River. This ring avoided strict geometric shapes to follow the terrain morphology organically. For Košice, no other plan of the 20th century placed as much emphasis on the city’s aesthetic values as this one, with its strongly evident application of the principles advocated by Camillo Sitte.

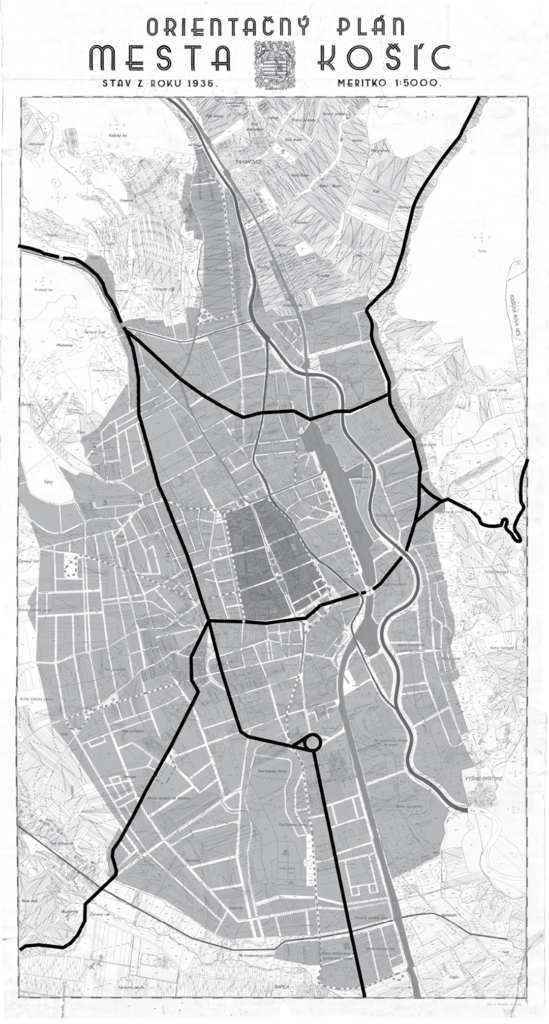

Era of the First Czechoslovak Republic

Despite its notably preliminary character, the plan essentially remained in effect during the First Czechoslovak Republic, though architects frequently deviated from it. When these diversions were necessary, new proposals were compared with Warga’s design, and drawings were made that resemble today’s practice of changing land use plans.

It took nearly 20 years for the next plan to be developed, the 1938 proposal of the Prague architect Dr. Josef Chochol, known primarily for his buildings designed in Cubist style. Itself a preliminary plan, it survives only through Chochol’s hand-drawn sketches10 in coloured pencils on tracing paper, and only the first 11 pages of the text are known. Based on this material, we have reconstructed Chochol’s proposal. His plan paid more attention to the precise localization of specific functions and less to aesthetic considerations. Like Warga and Lechner, his attitude to the ring roads is equally doubtful. Excluding the tram lines from Hlavná Street and placing new lines as close as possible to the edges of the medieval city, he made the line run along Moyzesova Street and the Mlynský náhon waterfront and, of course, in a transverse direction on the north and south. Consequently, the result was a new ring road much smaller than the existing one at the time, though perfectly accessing the center and creating conditions to eliminate vehicle traffic from Hlavná Street. On the other hand, the transverse breakthrough through the Old Town, involving the radical widening of Poštová and Bielá streets, was itself adopted from the plan by Warga and Lechner, thereby denying the very principle of the ring – to bypass the Old Town. Since this plan already had to confront the development of private car ownership, he proposed an outer traffic ring connecting intercity bus terminals, invariably located at the exit from the city towards the bus route’s destination. The green belt around the city was absent from his proposal, with the proposed greenery taking the form of scattered patches. However, Chochol submitted his plan to Košice only shortly after the First Vienna Arbitration of November 1938, which ceded the city to Hungarian control, and the authorities subsequently ended cooperation with him.

The Post-War Period and Today

The post-war plan by Bohuslav Fuchs survives only as a physical model11, which does not provide enough information for analyzing the central part of the city. However, it is possible to discern an intent to create a ring road around the city, primarily running through undeveloped areas, which relieves the city of through traffic but does not significantly impact the city’s appearance.

František Kočí’s plan12 was a product of Socialist Realism, which viewed the ring roads modelled after Vienna and Budapest as a product of monarchy and capitalism. However, the existing ring road was largely preserved, though the architect’s chief focus lay on creating direct streets – distinct urban axes ending with tower-like landmarks – and designing various monumental squares for massive public gatherings.

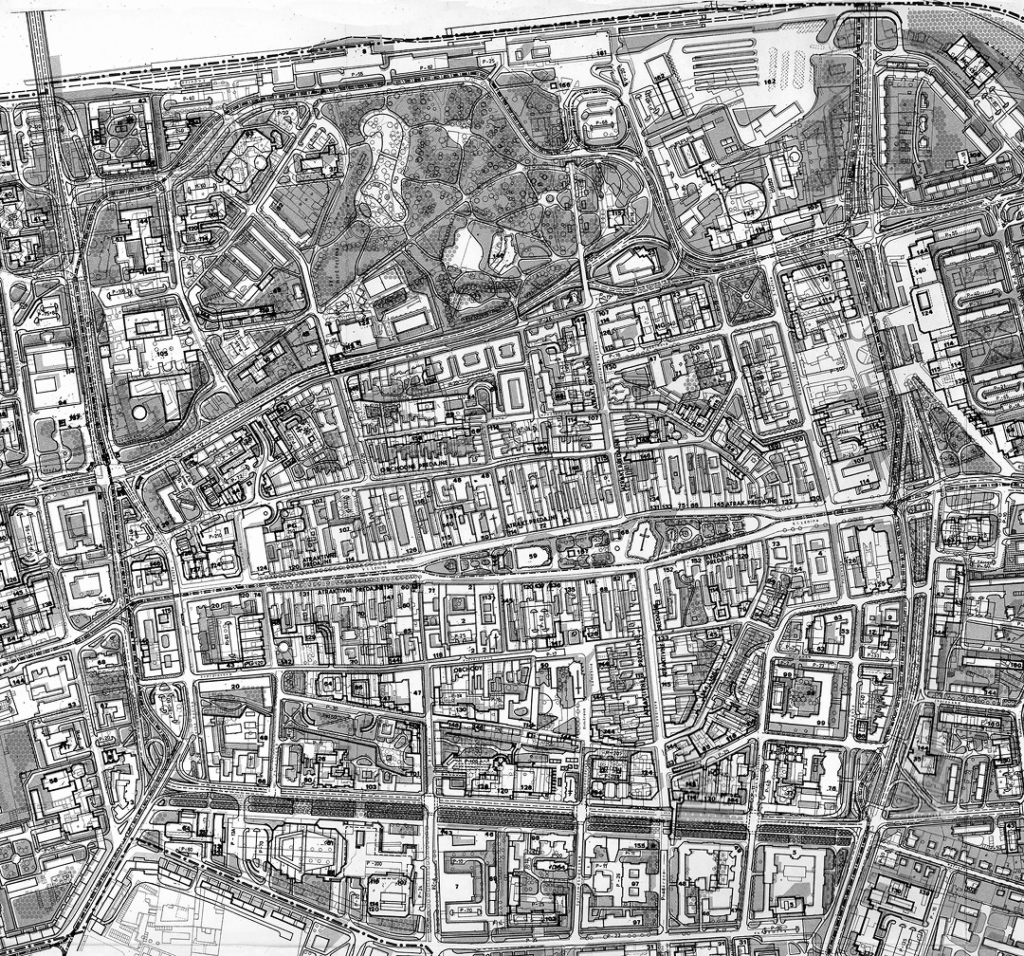

The next plan was prepared in Košice by the architect partnership of Hladký, Kurča, and Bányai,13 followed by the 1972 plan by Vlasta Michalcová.14 Both plans addressed primary attention to the dramatic increase in the city’s population as a result of the construction of the steelworks and other industries, and the integration of surrounding municipalities into the Košice agglomeration. Largely implemented, these proposals led to the redevelopment of significant areas of the old city and the transformation of Košice into a city for automobiles – as such, additionally affecting the ring roads and their adjacent areas. We will examine these proposals through the detailed regulatory plan of the central zone15, as the city-wide plans are notably sparse in detail. Bringing radical change to the appearance of the ring roads, this plan suggested extending Masarykova Street to the new Furča housing estate, where it would provide access to the city centre for the estate’s 30,000 residents. The traditional burghers’ houses on Masarykova were all planned to be demolished and replaced with large new public buildings as isolated volumes amidst greenery. Similarly, Moyzesova Street saw the demolition of the barracks for a new theater, with only two blocks remaining on the opposite side. New buildings were proposed from Poštová Street to the synagogue, each individually designed, while for Štúrova Street, only a few old buildings would be. Most significantly, the entire ring was designed for automotive traffic. Major intersections had multi-level crossings, while simpler cases featured underpasses, with ample parking spaces along its sides; pedestrians were consigned to underpasses and overpasses. Almost nothing from this project concerning the ring road was realized.

This proposal is a significant representative of the irresponsible application of the principles of the Athens Charter for city centers – which, as we know, failed to recognize the urban core as a functional zone. Additionally, this design is characterized its strong disrespect for cultural heritage, and its failure to recognize or ignore the genius loci.

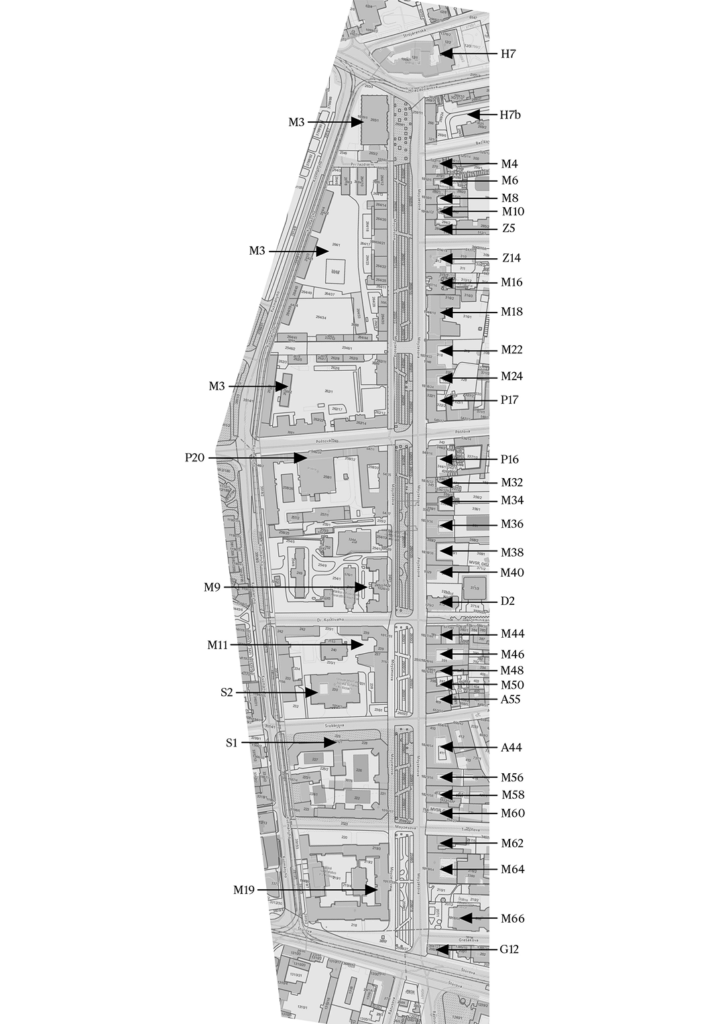

Building the Ring Roads on the Western Glacis

Each of the three segments of the ring road had a different character, lacking the stylistic unity seen in Vienna and Budapest. The most cohesive image was provided by the solution for the western glacis – Moyzesova Street. In the mid-19th century, a four-row linden avenue – a promenade – was planted on its western half. This avenue – promenade became a pride of the city. The fact that the term “ring road” was only introduced around the 1880s indicates the ambiguous contemporary vision of the city’s future image and functionality.

It was this exclusive are where the city directed its most important investments for state institutions, designed by leading Budapest architects within the blocks delineated by the Ott plan. However, the first complex to arise on the western glacis was that of the artillery barracks (Adolf Soukup16). For financial reasons, the city was strongly supportive of the construction, but it also elicited protests from residents17. After the barracks were built, complaints continued as residents were bothered by the stench and insects from the stables. Eventually, even the chief engineer of Košice had to admit that the construction of barracks in this location should not have occurred and was unsatisfactory from a hygienic perspective.18 The newspaper Kaschauer Zeitung criticised the construction in Košice, where instead of public buildings surrounded by parks, the new construction consisted of barracks, stables, and riding tracks, while even the sidewalks were used by the military for exercises. Vienna’s Ringstrasse and Budapest’s Körút were cited as positive examples.19 The concentration of various barracks on the ring road and in its immediate vicinity was not only bothersome but indeed overwhelming: up to half of the avenue’s length was occupied by the barracks, the covered riding track, and the open hippodrome.

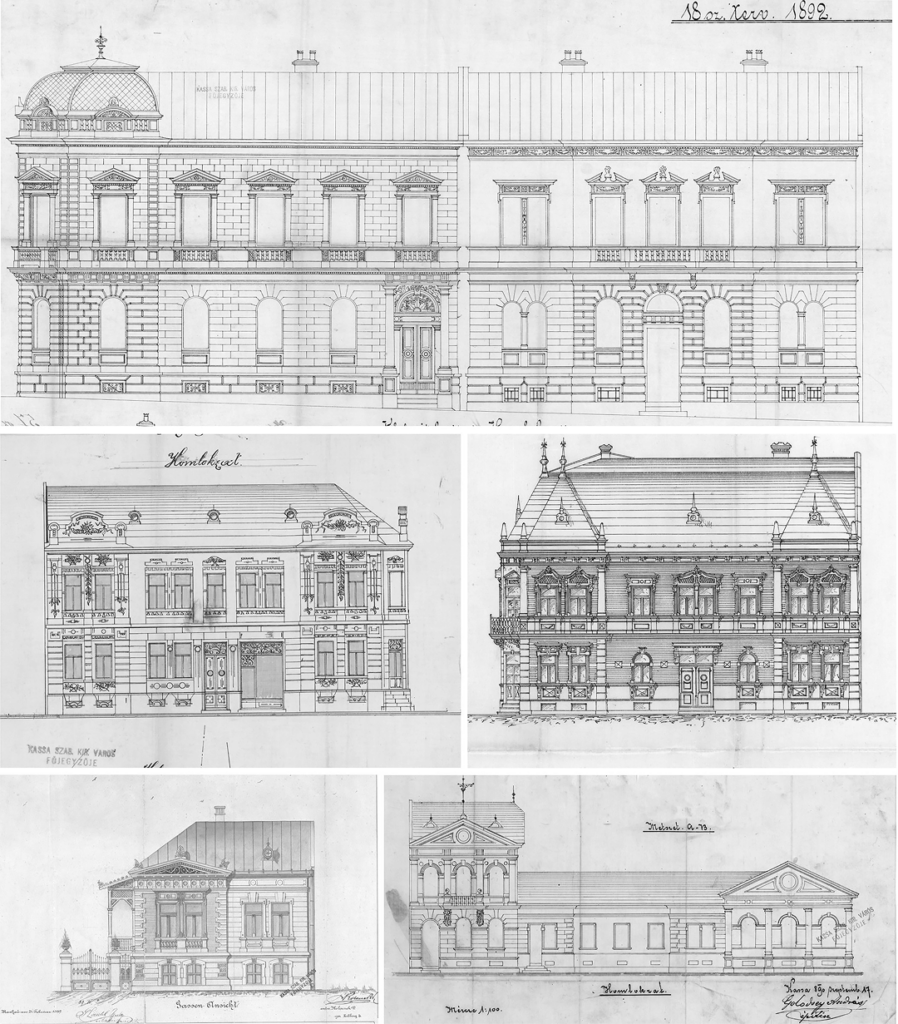

Among the significant public buildings later completed, one notable instance is the grand historicist building of the Hungarian Royal Court of Justice by Budapest architect Gyula Wagner. Other buildings on the ring road included more modern Secessionist architecture: the Higher Girls’ and Boys’ Schools and dormitories by Gyula Pártos, and two buildings by Sándor Baumgarten – the Higher Commercial School (Baumgarten and Herczeg) and the adjacent Hungarian Royal School of Midwifery, along with an orphanage in the courtyard (designed by Lajos Ybl). Visually, the composition at the northern end was completed by the axial bay of the Notary training building and dormitory by architect György Kopeczek (1912). Contributions from the interwar period include the Police Headquarters (František Sander) and the Main Post Office (Bohumír Kozák, 1931); additions from the socialist period are less pronounced. Although Košice’s Secessionist buildings were designed by prominent Budapest architects, these buildings are among their lesser-known works, and Košice’s fin-de-siecle heritage does not match the level of cities like Szeged (HU) and Kecskemét (HU) or Subotica (SRB) and Oradea (RO) in the territory of pre-1920 Hungary. The arrangement of the street shows a dichotomy. While the western side was used for significant public buildings representing the state, the eastern side adjacent to the city is almost exclusively occupied by private and ecclesiastical buildings. While the western side was built mainly by Budapest and later Czech architects, the eastern side was constructed by local architects and primarily local master builders. These were entrepreneurs focusing on both the execution and design of buildings, lacking formal university education. Despite this, many left valuable works. These were not pioneering works, but their efforts shaped the character of streets and squares not only in Košice’s ring road but across the entire Monarchy. The following text by Ákos Moravánszky also relates to Košice’s builders:

“It is not the singular outstanding achievement but the typical everyday architecture that makes a former kaiserlich und königlich garrison town in western Ukraine appear familiar to a visitor from Lower Austria. The railway station with its restaurant, the tree-lined main street leading to the market square with its town hall, savings bank, post office, and theatre can be easily recognised, even if some of them have changed functions several times. The place of these buildings in the hierarchy of the city – the familiarity of their inner disposition, the stucco ornaments on the façade, and even the colours (if the originals remain) – contributes more to the identity of the region than the masterworks of the famous architects. This building stock physically forms and formally expresses the unified infrastructure of the Habsburg Monarchy; this brick-and-plaster substance proved more resistant to historical erosion than the modernism of the 1920s and 1930s.”20

On the eastern side, noteworthy structures included the now-vanished Neolog synagogue with school (Mihály Répászky, addition by Otto Sztehlo, demolished 1958), the Greek Catholic church (Kolacsek and Schmiedt), the apartment building at the corner of Alžbetina (András Golodzsey) and the Tost house (Dénes Györgyi). The remaining buildings were rental apartment blocks for middle-class tenants, mostly designed by master builders rather than architects.21 From the period of the First Czechoslovak Republic on this side of the street, the Neolog synagogue (1926) is a noteworthy landmark; incidentally, its design by Lajos Kozma only received third place as a competition entry.22 In the courtyard of the Dominican Sisters stands a hidden functionalist church (Rudolf Brepta). Throughout the existence of the First Czechoslovak Republic, political rivalry between supporters and opponents of Czechoslovakism remained a persistent force. The opponents, often advocated for regional or ethnic distinctiveness. From an urban planning perspective, this rivalry manifested as an effort to visually dominate public space, evident in the language of inscriptions, street names, and the symbolism of artworks in public areas.23 Architecture, too, became a crucial tool in this ideological struggle, serving as a medium for expressing ideas of statehood and national identity. Three prominent public buildings on Moyzesova Street stand as witnesses to these efforts.

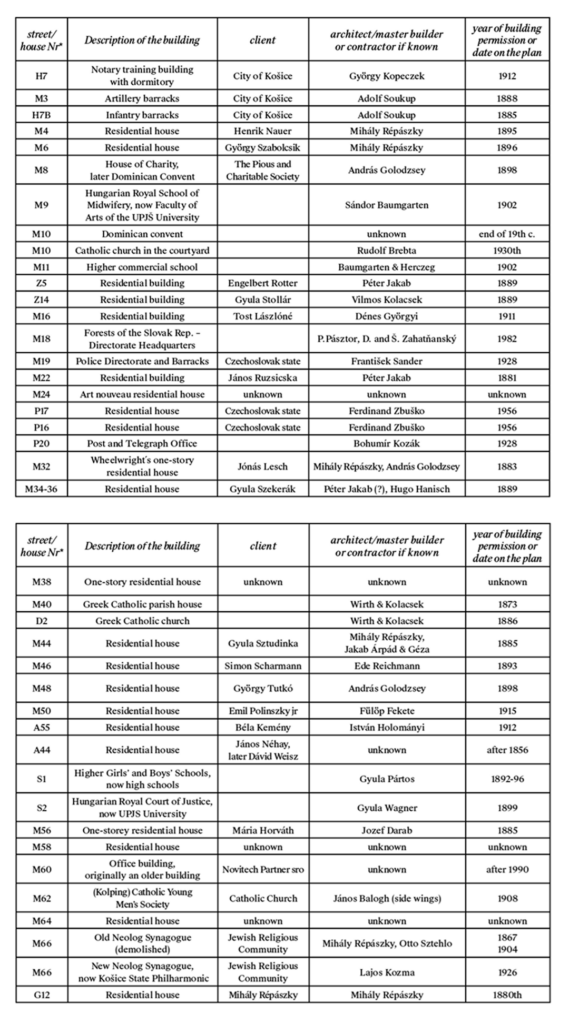

The Police Headquarters building embodies the National Style characteristic of the First Czechoslovak Republic during the 1920s. However, this style quickly lost its momentum, and by the 1930s, functionalism emerged as the defining symbol of the modern Czechoslovak state, exemplified by the Main Post Office building. In contrast, on the other side of the ideological spectrum, the synagogue designed by Budapest architect Lajos Kozma represents a Neobaroque form enriched with oriental decorative elements, reflecting a distinct cultural and artistic perspective. The socialist era of the 1950s includes the reconstruction of the Neolog synagogue into the State Philharmonic building (Leopold Czihal), two apartment buildings from the 1950s forming the entrance to Alžbetina Street (Ferdinand Zbuško), and an administrative building from 1982 (P. Pásztor, D. and Š. Zahatňanskí). However, the character of this side of the street is defined by the Gründerzeit period and the work of local master builders provides an overview of the buildings and their builders.

Who Who Were These Master Builders and Their Clients?

The social structure of the residents of the suburbs and inner city of Košice was studied by sociologist Gábor Czoch24.Moyzesova Street, as Czoch’s research reveals, marked the boundary between these two parts of the city, which in social composition differed quite dramatically. While the largest group of inner-city residents consisted of craftsmen (70%), followed by merchants (12%) and professionals (5%), in the suburbs, these same groups accounted for only 51%, 1.4%, and 2.7%, respectively. Meanwhile, agricultural workers made up nearly 30% of the suburban population, compared to a mere 4% in the inner city. In the inner city, Hungarian and German predominated, whereas Slovak was the dominant language in the suburbs; nonetheless, statistics show a gradual trend toward reduction these differences over time.

Czoch also cites older descriptions of the city. For example, Imre Henszlmann wrote in 1846: “With the exception of the farmsteads of the well-to-do burghers and the gardens of the nobility, the outer city consists of miserable thatch-roofed houses made of clay…”

The works of Budapest architects in Košice are well known, but the work of local builders has not yet been comprehensively mapped, and their contributions remain overshadowed by those of their architect colleagues. Among them were prominent entrepreneurs, such as Péter Jakab, the founder of the largest construction company in Košice, which also operated a brick factory, and Mihály Répászky. István Holományi built a beautiful Art Nouveau apartment house for lawyer Béla Kemény on the corner of Alžbetina and Moyzesova streets, while Fülöp Fekete built one for city engineer Emil Polinszky Jr. (no. 50). Other notable builders who constructed remarkable buildings along the ring road include András Golodzsey, Vilmos Kolacsek, István Forgács, János Balogh, and Béla Martoncsik. Research into their work would undoubtedly yield fascinating insights.

The social status of the residents of Moyzesova Street is reflected in their houses. Wealthy individuals commissioned homes on this street, corresponding in size to their affluence. One owner even had two large apartment buildings constructed on the street. The most famous resident was László Tost25, mayor of Košice, politician, secretary of the Christian Socialist Party, and member of parliament, who was murdered by Hungary’s fascist Arrow Cross forces at the end of the war.

On the Northern Glacis

Similarly, the northern sector is far from uniform. In its western part, a series of representative public buildings were erected, starting with the already mentioned notary course building, sided by the primary school (Karol Bayer), followed by the Neo-Renaissance building of the Museum of Upper Hungary (Répászky, Jakab). On the eastern side are two large-scale buildings: the military command building (József Kauser and Adolf Soukup, 1908) and the Košice-Bohumín Railway Directorate (József Hubert, 1915). Beyond the Millrace brook, the straight avenue, lined with private houses, continues towards the railway, an urbanistic achievement opening for new construction previously undeveloped areas of Újváros [New Town]. Again, we can observe an effort towards the previously mentioned grid arrangement of streets. As with the western glacis, the character of the broad street here is also determined largely by local master builders. During the First Czechoslovak Republic, Functionalist architecture also made its appearance (Pál Gyulai, Alois Novák). Far more radical changes, though, were imposed through post-war development. More than half the length of the northern side was demolished and replaced by a massive trade union building with a large open space in front of it (Miloš Chorvát, 1974). On the opposite side, the unremarkable building of the railway hospital resulted in the loss of several beautiful earlier historicist buildings. However, the double row of trees preserved from the original concept partially conceals these interventions.

On the Southern Glacis

While the northern and western glacis were developed in an elegant style, the southern part of the ring road remained a busy national roadway. Adjacent to the city, residential buildings arose, while in front of the former southern gate was an irregularly shaped large square serving as a bustling market. The southern side of the street, by contrast, was predominantly occupied by industrial buildings: a sharp dichotomy that significantly formed the street’s character. On the north side were tenement houses in a historicizing style, joined during the First Czechoslovak Republic by several functionalist buildings. On the southern side stood premises of industrial enterprises. While the facades of these businesses resembled ordinary residential buildings, containing apartments, offices, and shops, behind them, in the rear courtyards, lay manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and wholesale businesses. The pride of the industrialists were the factory chimneys, indicating that the enterprise had steam power. Businesses came and went, moved to different locations, and new ones arrived. Among the changing manufacturing facilities of the street were several distilleries, the Sztudinka furniture factory, the Siposs weaving company, the Poledniak machine factory, and the Fiedler sugar refinery. On the western side, the view was closed off by the massive volume of the Bauernebl brewery’s malt house.

A critical point was the market square, a space filled with unattractive shanties and vendor stalls; moreover, the farmers arriving via Pest Street on market days caused traffic jams with their carts. On the square stood the Uránia cinema (Gyula Sándy), after which the street then continued northward out of the city, passing other industrial facilities, a machine shop, the tram depot, and the municipal gasworks towards Prešov. The elegance of Moyzesova and Masarykova streets was entirely absent here. When Košice was part of Hungary during World War II, the city’s significance increased as a sought-after tourist destination and winter sports center. Correspondingly, the city council considered the state of the square embarrassing and proceeded with its reconstruction. By the end of the war, a section of the road to Prešov was built, the square was paved, and a new attraction – an illuminated fountain – was installed. At the same time, a row of trees was planted on Štúrova Street, not as a pedestrian promenade like Moyzesova, but in the middle of the roadway within the tram tracks. Unfortunately, the new architectural plan for the square is unknown: a possible reconstruction of its appearance might be deduced from the simple scheme published in a tourist guide26. This space, though, was no longer meant as a public square created by autonomous citizens, the outcome of their individual taste and financial possibilities. The liberal period during the war had ended: now, it was to be a square representing the idea of the resurgent Hungarian state, expressed among other things by a statue of Hungary’s then ruler Regent Miklós Horthy and an equestrian statue of the anti-Habsburg rebel Ferenc Rákóczi. As planned, the square would be outlined by buildings representing state and municipal institutions.

In the post-war period, many plans were created for the redevelopment of the square, each reflecting the current state idea, and the basic rectangular shape of the square defined during the war years. Today, after the construction of a large shopping mall, only a small portion of the square remains. The southern part of the ring road has been the most redeveloped since 1945 and is the most burdened with traffic and noise; for the purpose of promenades, as planned by the commission in 1870, it is unusable.

Conclusion

When we trace the development of the Košice ring road on historical maps, we must note the uncertainty in designating streets as ring roads, which can be attributed to the long-term lack of a clear concept for planning the ring and the fact that no street had a definitive ring shape. While on Homolka’s plan (1869), none of the Košice streets were marked as “körút” [ring road], by a map published in 189627 and by 1906, there were two streets identified as such.

In the local press, we recorded the first occurrence of the word körút in connection with Košice as late as 189128 (Kaschauer Zeitung).

By the 1912 plan29, there were seven ring roads forming a genuine traffic circle. Trams ran along its entire perimeter, and the ring connected the city’s most important buildings. During the First Czechoslovak Republic, the designation “ring road” appeared on maps published in 1925 and 193830 for the same streets as in 1912. On the Hungarian map issued in 194231, an eighth ring road was added along the Millrace. In the post-war period, the 194932 map still used the term ring road, but by 1951, only one ring road was indicated. After this period, with the renaming of streets and the advent of the new regime, the term “ring road” disappeared in Košice.

We did not find the use of the term Ring or Ringstrasse in the local German-language newspaper, Kaschauer Zeitung (1841–1914). They used the same terms, Gasse or Strasse, e.g., Klobusitzky Gasse, for ring roads as for regular streets. More frequently, however, in German texts, the Hungarian term, e.g., Rákóczi körút, was used. The Slovak and Czech terms okružná/í are known only from the First Czechoslovak Republic and a few early post-war years.

This linguistic evidence indicates that the Košice ring roads never formed as prominent a part of the city’s image or genius loci as in other similar cities. Ring roads in Vienna, Budapest, Brno, Szeged, and many other cities are integral to the city’s genius loci and, unlike the Košice ring roads, significantly shape the city’s image.

Physically, the Košice ring roads unquestionably exist and play an irreplaceable role in the city’s transportation system. However, their other functions, such as commerce or providing spaces for social life, are fulfilled only to a limited extent. The length of the Košice ring, if we consider it from the north from the railway, through Moyzesova and Štúrova Streets to the station, is 4.4 km. The “reduced” ring, i.e., Moyzesova – Štefánikova along the former Millrace and their connection to the north and south, is 3.6 km long. Comparing this with Budapest’s Nagykörút at 4.7 km and Vienna’s Ringstrasse at 4.1 km, we understand that a city the size of Košice, moreover over a century and a half ago, could not cover such a long stretch with attractive buildings or fill the space with commercial and social life. Yet even beyond the length of the ring, the absence of such an urban formation is the outcome of inadequate planning and the placement of functions unsuitable for the site, such as military barracks.

As we have seen, none of the city’s previous urban plans assigned the ring road its appropriate significance. Their designs even included controversial solutions, such as transverse axes that, in addition to disrupting the unified appearance of Hlavná Street, directed social and commercial life away from the ring. Even further, the socialist era significantly harmed the ring roads. The emergence of ring boulevards is a hallmark of urbanism associated with rising capitalism and the liberal society of today’s type. In our part of Europe, this was also a product of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, from whose heritage the regime distanced itself.

But the most crucial factor diverting the city’s social life away from the ring is the presence of the unique kilometre-long Košice Square, or Hlavná Street with its marvellous architecture, numerous public buildings, and centuries-old traditions. These are the reasons that prevented Košice’s ring boulevards from developing into attractive areas and gaining a more prominent position in the city’s image – and equally provide explanation for the title of this article.

This paper was supported by the VEGA agency

(Grant no. 1/0371/22), and a fellowship

of the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2020. Little Vienna – Little Budapest: Ring Boulevards of Three Midsized Towns in the Habsburg Empire, 1848–1920. In: Thomas, A. et al. (eds.). Yearbook of Transnational History 3. Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, pp. 33–54; EKLER, Dezsö and TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2016. Ringstraßen im Vergleich: Varianten auf eine städtebauliche Idee in Wien, Budapest und Szeged. In: Hárs, E. et al. (eds.). Ringstraßen: Kulturwissenschaftliche Annäherungen an die Stadtarchitektur von Wien, Budapest und Szeged. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, pp. 25–62.

HUNGARICANA – KÖZGYŰJTEMÉNYI PORTÁL. 2024. A magyarországi népszámlálások adatai 1784 és 1990 között [online]. Available at: https://library.hungaricana.hu/hu/collection/ksh_neda_nepszamlalasok/ (Accessed: 12 August 2024).

LAHMEYER, Jan. 2003. SLOVAKIA historical demographical data of the urban centers [online]. Available at: http://populstat.info/Europe/slovakit.htm (Accessed: 12 August 2024).

SZABÓ, J. B. et al. 2013. Parallel Histories – Budapest and Kassa/Košice: The Capital and Center of Region in the second half of the 19th Century. Budapest: Budapesti Történeti Múzeum.

DUCHOŇ, Jozef. 2022. Naše mesto v 18. storočí POSLEDNÝ TEREZIÁNSKY PLÁN. Košice online [online]. Available at: https://www.cassovia.sk/sk/nase-mesto-v-18-storoci-posledny-tereziansky-plan (Accessed: 12 August 2024).

BAUER, Juraj. 2016. Svedectvo starých máp mesta Košice. Košice: published by the author at their own expense.

DiFMOE. 1832. Plan der königlichen Freistadt Kaschau: Aufgenommen und gezeichnet von Joseph Ott, Privat Ingenieur. Bibliothek des Digitalen Forums Mittel- und Osteuropa [online]. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y96y2lcw (Accessed: 18 July 2018).

A Kassa szab. kir. város fejlődési érdekeinek előmozdítása tekintetében kiküldött u. n. 30-as bizottság pénzügyi és építészeti albizotságainak jelentéseik. 1870. Kassán: Nyomatott Werfer Károly akad. könyvnyomdájában.

HOMOLKA, Jósef and MYSKOVSZKY, Viktor. 1870. KASSA Szabad királyi városának térképe 1869 [online]. Buda. Available at: www.slovakiana.sk (Accessed: 12 August 2024).

CHOCHOL, Josef. 1938. Upravovací plán Košice [scale 1: 5000]. Fond 94 – Josef Chochol. Archives of the National Technical Museum Prague.

FUCHS, Bohuslav. Model smerného plánu [scale 1: 10 000]. 1950(?). Private archives of architect Marek Merjavý, Košice.

KOČÍ, František et al. Smerný plán Košíc, základný výkres [scale 1: 5 000]. 1953(?). Private archives of architect Dušan Hudec, Košice.

HLADKÝ, Milan et al. SÚP Košice, základný výkres [scale 1: 5 000]. Private archives of architect Alexander Bél, Košice.

MICHALCOVÁ, Vlasta. Smerný územný plán hospodársko-sídelnej aglomerácie Košice: Materiál na rokovanie vlády SSR. Bratislava: VsKNV a Min. výstavby a techniky SSR, 1974. Archives of ÚHA Košice.

BÉL, Alexander et al. Územný plán celomestského centra, Stavoprojekt Urbanistické stredisko Košice. Urbanistický návrh, výkres. č. 2. Private archives of architect Dušan Hudec, Košice.

Adolf Soukup was a military engineer, also serving as the Chief City Engineer of Košice, and a specialist in military constructions. His work spanned the entire Kingdom of Hungary; besides the barracks and the Military Command Headquarters in Košice, military barracks of his design are attested in the cities of Tolna (H), Osijek (HR), Užhorod UA), Nyíregyháza (H), and Subotica (SRB).

Kaschauer Zeitung. 1885. Stimmen aus dem Publikum. Kaschauer Zeitung: Kassa-Eperjesi Értesitö, 48(29), p. 3.

Abauj-Kassai Közlöny. 1908. A városrendezés kérdéséhez. Abauj-Kassai Közlöny: politikai és vegyes tartalmú hetilap, 37(68), p. 1.

Kaschauer Zeitung, 24 january 1895, 57(11).

MORAVÁNSZKY, Ákos. 1998. Competing visions: Aesthetic invention and social imagination in Central European architecture, 1867–1918. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. x–xi.

Kolacsek & Schmiedt, András Golodzsey, Árpád a Géza Jakab, István Forgách…

Kassai Ujság. 1926. Az új zsidó templom tervpályázatának nyertesei. Kassai Ujság, 88(45), p. 4.

FICERI, Ondrej. 2017. Czechoslovakism in Mentalities of Košice’s Inhabitants and Its Implementation in the Public Space of the City in the Interwar Era. Mesto a dejiny, 6(2), pp. 22–47.

CZOCH, Gábor. 2012. The Transformation of Urban Space in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century in Hungary and in the City of Kassa. Hungarian Historical Review, 1(1–2), pp. 104–133.

SZEGHY-GAYER, Veronika. 2022. László Tost: mešťanosta Košíc. Košice: Fórum Maďarov v Košiciach.

SCHERMANN, Szilárd. 1944. Kassa és a Kassai hegyek kalauza. Budapest: A Magyarországi Karpát Egyesület.

KOGUTOWICZ, Manó. 1896. Kassa sz. Kir. Város térképe [no scale]. Budapest: Kogutowicz és társa Magyar Földrajzi Intézete.

Kaschauer Zeitung, 1891, 53(121), p. 4.

Kassa törv. hat. jog. fel. szab. kir. város belsöségének és környékének átnézeti térképe [scale 1:10000]. 1912. Budapest: M. kir. 1. felmérési felügyelöség Kassán.

Orientačný plán mesta Košíc [no scale] [papier]. 1938. Košice: Litografia WIKO.

Kassa thj. sz. kir. város átnézeti térképe [1:10000] [papier]. 1942. Budapest: M. kir. Honv. Térk. Int.

Plán mesta Košíc [no scale] [papier]. 1943. Košice: Litografia WIKO.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2024.58.3-4.8

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License