In 1872, the municipal authorities of Budapest decided that the city should have three ring roads. Of these three, the outermost suburban ring took 120 years to complete, during which time urban concepts changed significantly. The original idea was an urban promenade surrounded by apartment and public buildings in a green environment. When the northern section of the road was realised by the middle of the 20th century, the intention was to develop the surrounding territory into a housing estate with a public centre around its main traffic junction. In the late 1960s – affected by motorisation – engineers worked out a highway concept for the ring road. Finally, the southern section of the ring was built in a single impulse, bringing together functions especially adapted to car-dependent consumerism.

The official intention to create the Hungária Ring Road [Hungária körút] of Budapest emerged about 120 years ago. Since a period of over a century represents a considerable time in the development of a city, we should consequently turn to urban morphology to reveal and explain what has changed in the interval. Although there are several schools for this discipline, we prefer the recent concept of Karl Kropf.1 However, we follow his method only in analysing the road in its political and urban intentions, along with the constraints through the architectural remains of the different periods up to the present characteristic sections. As our focus is on history, we do not include the analysis of stocks and flows, which would help improve the present urban situation.

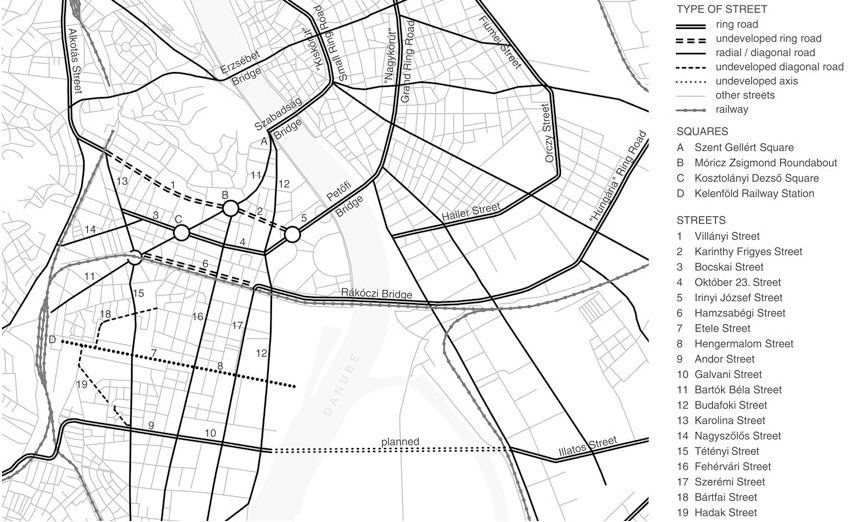

As originally intended and currently realised, the line of the Hungária Ring Road runs from the Northern bank of the Danube up to the Southern bank. The present course of the ring hardly changed during its implementation. However, its development can be divided into four phases following the main political and urban intentions: the promenade, the north bridge connection, the unrealised idea of a highway, and the south bridge connection.

The Promenade

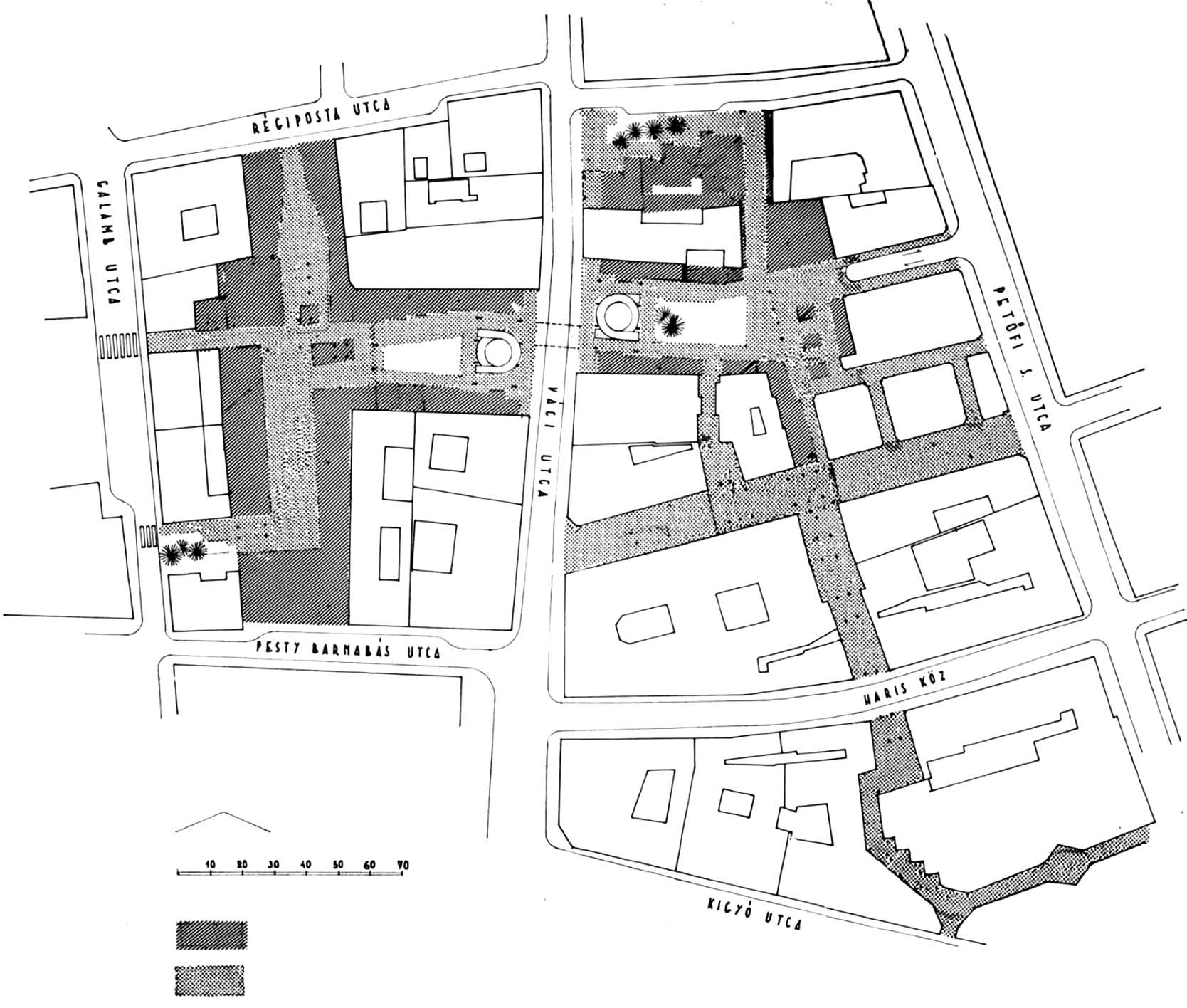

In March 1871, the newly established Metropolitan Public Works Council [Fővárosi Közmunkák Tanácsa] announced an international competition for the regulatory plan of Budapest. The task was comprehensive, and the material to be submitted was enormous. Though the main structure of the city was already prepared and suggested to the participants, adherence to the set format was optional. The jury expected to establish the position for the squares, the parks, the main roads, and the city’s water and sewerage system.2 Additionally, the tender listed all the public buildings for which the applicants had to find the ideal situation in the interest of beautifying the city. Not surprisingly, only ten submissions were received by the deadline of November 1871, and as announced in advance, only the first three applicants were awarded. The tender result showed that the jury preferred the proposals that accepted the suggested urban structure.3 As such, the entry that received second prize approached the proposed ring road – avenue system with a plan for four ring roads, three of which were connected to the river Danube at both ends.4 In turn, the final city plan was based on an almost identical concept, while the residential zone assignment of 1873 used the four ring roads to mark the borderline between the different building ratios.

In the following years, the city authorities concentrated on developing the two inner boulevards (the Small and the Grand Boulevards), but the municipality also assumed the future construction of the two other ring roads. The Metropolitan Public Works Council presented their concept to the Town Public Architecture Commission

[Városi Középítészeti Bizottmány], which the city accepted in 1872.5 The authorities quickly welcomed the decision on the third and fourth ring roads. While the third ring was never completed, realising the fourth one took an extremely long time. Formally, the period from original concept to completion took 132 years, while the road’s physical development spanned about 120 years. One partial explanation is that Budapest suffered from a lack of money, for example, compared to Vienna in the case of its own ring system, as the city had to pay for almost every suitable site.6 From another aspect, this time spans several generations, over which the political situation and urban concepts changed repeatedly and significantly.

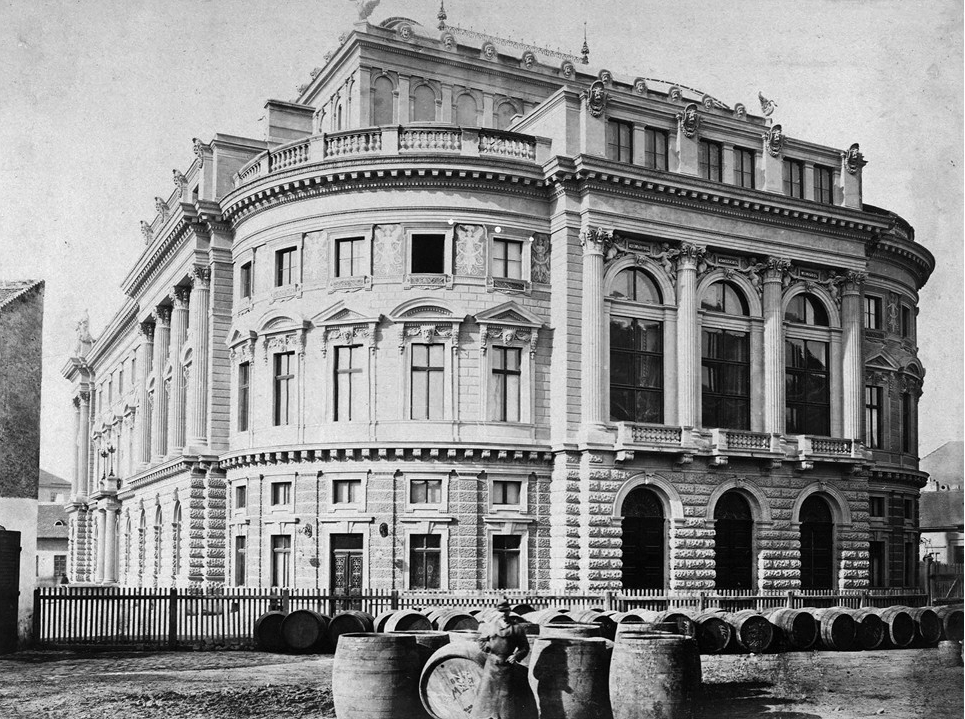

Compared to the inner-city rings, the territory of the planned suburban ring ran through an almost undeveloped area. Its line was marked with a street only at its middle section, while it avoided intersection with the roads towards the river Danube in both directions. Indicative of its physically peripheral position is the very name of the street that formed its core: Hajcsár [Hungarian: drover, herdsman] Street. The road’s connection to the town was the City Park [Városliget], created and developed during the first part of the 19th century. However, the park also marked the border between the city and the outskirts, as the Pest-Cegléd railway line, created in 1846, ran parallel to Hajcsár Street, while also closing the street leading towards the North. The development of the ring road started with the construction of a tunnel under this railway in 1875.7 Though narrow and intended only for pedestrians, it opened a connection to the rest of Hajcsár Street. Then, road construction soon began on the still unbuilt territory. In 1883, the Budapest press reported on two almost-finished developments.8 One was the military complex of the artillery barracks, and the other was the Hungarian Royal Mental Hospital on the opposite side of the street.9 Both functions needed a relatively large area, as they consisted of physically separated pavilions.

Hajcsár Street, following the line of the City Park, received its new name of Hungária Boulevard in 1881.10 The paving of the road was completed a year later, in 1882.11 However, the following years did not radically change the story of the newly named boulevard until a new concept put development back into motion. By the end of the decade, the pressures on the City Park had risen drastically because of the different functions the city’s growing population intended for it. Initially, it acted as a park, a piece of nature, and a place for appointments, like the Bois de Boulogne in Paris. However, soon, the park included a zoo, restaurants, and an amusement park, even serving as the site of a national exhibition in 1885. This overuse led the city, especially its Promenade Committee [Sétányügyi Bizottság], to accept the proposal to create another city park in the southern part of the town.12 The future People’s Park [Népliget] was planned on a pasture between a city-owned forest and a private tree nursery. Beyond its consisting of unbuilt land, it had another advantage, namely that the city had already developed a residential area in that direction. The Association of House Building Officials, founded in 1883, completed 202 houses between 1886–189013 and were moreover the owners of the land extending up to the nursery. And indeed, the street between the colony and the nursery garden largely overlapped with the planned routing of the ring road. Quite soon, the authorities decided to develop the People’s Park, adding to it the territory of the former tree nursery.14

This decision offered a major stimulus to the development of Hungária Boulevard, specifically the practical advantages of connecting the People’s Park with the City Park. Keeping the previously planned line of the outer ring was possible because the capital still owned the land under consideration.15 Yet even after the official decision, some questions still emerged. In 1872, the width of the ring road was fixed at 33 meters.16 Two decades later, the authorities had ceased to discuss it in terms of an urban ring road from the Danube to the Danube but instead a promenade between these two large city parks. The new approach also stimulated reflections on the possibility of using the planned People’s Park as an exhibition site. By 1891, it was already agreed that a huge exhibition would be organised in 1896 to celebrate the thousandth anniversary of the arrival of the Hungarian people to the Carpathian basin, yet the authorities had yet to resolve its site. Among other proposals, the People’s Park was suggested. However, it turned out that completing the People’s Park in due time would be impossible, and the Millennial Exhibition would be organised in the City Park. However, this change did not override the idea of building a connection between the People’s Park and the City Park; instead, a demand arose that the road be completed by 1896, for the opening of the Millennial Exhibition. The following years were spent discussing the proposed road’s width, with the Municipal Public Architecture Commission proposing different widths for the various sections17 and the Metropolitan Public Works Commission insisting on keeping the same scale. Namely, the road would be widened to 45.5 m and be conceived as a promenade, in which pedestrian, equestrian, and carriage traffic would have separate lanes. As the two commissions could not agree, the minister of interior affairs finally decided on the broader version, though applied only to the section between Stefánia Street and People’s Park.18

The design of the People’s Park and the Millennial Exhibition in the City Park forced the development of the Hungária Boulevard before the decade’s end. However, further changes also had their place in making it necessary. In 1894, the city administration laid claim to four military barracks in the inner city, plus the Citadel at the top of Gellért Hill.19 Budapest paid the army compensation, but also had to find an appropriate area for new military barracks in the outskirts. One army barrack was already positioned at the upper (Northern) part of the Hungária Boulevard, and an army hospital was under construction on the opposite side of the street.20 Soon, the new military barracks arose along the southern section of Hungária Boulevard; since a cavalry regiment was also housed there, it was expected that the equestrian promenade would also serve them. Additionally, the combination of a completed public road and sizeable unbuilt sites along it became attractive to the city council, hence the city settled its new Institute of Bacteriology opposite Stefánia Street in 1898–1899.21 The pavilion system of the buildings was consistent with the function.

In 1895, the decision on the width of the Hungária Boulevard was fixed only for the individual section between Stefánia Street and People’s Park. As mentioned above, the middle section of the road ran along the City Park, with small plots on both sides, all on a scale defined by the planned function, namely summer cottages amid natural vegetation. The question of the width of the Hungária Boulevard emerged when a public building was proposed for one of the larger plots: this was the National Institute for the Blind, which was not a new initiative but rather an existing institution planned for relocation outside the city centre. The design also included the Erzsébet Girls’ School, so the mass of the whole complex was enormous.22 And even when the problem of the building mass was rapidly solved, the positioning of the complex – namely the width of the Hungária Boulevard – led to a dispute between the authorities. In this case, the city council took a position of 44.5 meters, while the Metropolitan Public Works Council and the Minister of Culture wished to keep the figure of 33 meters. Finally, it was the minister for interior affairs, once again, that decided on 44.5 meters. He also established that the whole of Hungária Boulevard would adhere to the now-set width, except for the tunnel below the rail line at Hajcsár Street.23

The Northern Bridge

The Elizabeth Bridge [Erzsébet híd], running from the old urban core of Pest and leading to Gellért Hill, was completed in 1903. This development directed the attention back to the uncompleted Hungária Boulevard, which still lacked any connections to the Danube. It appeared easier to complete its northern section: the military barracks, the hospital and the mental asylum were already standing, while the rest of the territory of the planned ring road was almost unbuilt. However, another decisive aspect lay on the opposite side of the river: the settlement of Óbuda, literally “Old Buda”, was undergoing considerable development, including industrial structures. A law for the planned bridge at this point was passed as early as 1908.24

Compared to the southern bridge possibilities, this connection seemed more important and, at the same time, cheaper to implement, though it still required significant investments. Not long after, World War I harshly cut off all new construction. Although the city had no wish to abandon the project – even preparing several versions for the alignment of the bridge – it is not surprising that the Metropolitan Public Works Council announced the architectural competition for the Óbuda bridgehead only in 1937.25 Almost parallel with the competition came the decision for the new names of the planned ring road, calling them Róbert Károly, Hungária and Könyves Kálmán Ring, representing the seriousness of the builders’ intention.26 Since the architectural planning of the bridgehead at the Pest side seemed more straightforward, its preparation was assigned to the Metropolitan Public Works Council, which planned a circular square with a roundabout for intersection of the ring road with the radial Váci Street while assuming a residential area on both sides of the bridgehead.27 Work began on construction of the bridge, but was soon interrupted due to World War II.

In 1947, after the war, the Metropolitan Public Works Council prepared a new version for the bridgehead of the Pest side.28 The city authorities stressed that the Hungária Ring Road should be completed and a tramline laid along it, hence the new plan incorporated these requirements. The road connecting the bridge with the ring was now elevated, while Váci Street crossed it from below. According to the plan, both corners of Váci Street and the ring road would be assigned for public facilities, while apartment blocks of 6–8 storeys among open green spaces would arise on both sides of the bridgehead. The newspaper announced the construction of the first public building on the southern corner of the junction in 1949. Functionally, it combined a district cultural centre and a housing block due to the requirements of its architectural competition.29 In August 1950, following the Communist seizure of power, the public building began to be presented as the District Headquarters of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, including a ceremonial hall with a stage for celebrations.30 Completed on time, the new bridge was named after Joseph Stalin, not surprisingly considering that Hungary was undergoing its period of strongest Communist rule. However, except for the building mentioned above and the bridge itself, nothing was realised from the announced housing estate intended to follow “the principles of Soviet urban architecture.”31

The public authorities returned to the development plans only after the defeat of the revolution of 1956. Since socialist realism had already fallen from favor in the architectural sphere, the proposals submitted for the new competition for the area already represented conventional modernist architecture.32 The complex design program included the traffic junctions, a local city centre with public buildings, and large-scale housing estates at both sides of the bridgehead. Here, the proposals for the local city centre and public buildings were granted significantly greater roles than in the previous settlement plans. And it must be said the Árpád bridge (which regained its original name) and especially its bridgehead had a particular position in the late-socialist Kádár era. Always a workers’ district, including Váci Street as its main radial road, the junction between Váci Street and the Hungária Ring Road was thus politically important. The eight award-winning projects displayed standard features. All the applicants connected the bridge and the ring road with an elevated roadway with the trajectory of Váci Street routed beneath it. Public facilities were, in turn, invariably concentrated on the street level around the Váci – Hungária intersection. The jury also concluded that the position of the district centre should be at the crossing. However, in the following years, construction works concentrated on housing. The estate north of the bridgehead developed slowly and was completed – along with smaller-scale public facilities like schools and kindergartens – by 1965. Some public functions were later situated on the ground floor of the apartment blocks along Váci Street, but the formal district centre was developed only later.

The 1957 architectural tender already assumed the presence of high-rise buildings. Their number, though, would be few, and the proposals positioned them at different parts of the territory. Even the jury evaluated the high-rise as more of an architectural gesture calculated for later implementation. As it happened, the first high-rise building was realised more than fifteen years later, in 1973.33 By then, it was evident that the district centre would be created at the Váci Street – Hungária crossing. Arguments in favour for the final positioning of the high-rise cited the vital traffic junction, the (still planned) express tram along the ring road and the planned metro line under Váci Street. Built as headquarters for the Hungarian trade union, the structure included offices and additional functions, with the usual arrangement of a combination of tower and flat mass. At 72 meters high, then the highest building in Hungary, the office building was the first element of a planned district centre. The subsequent addition would be a catering complex, including a self-service cafeteria, a beer hall, and a large self-service supermarket.34 Unfortunately, the territory became too valuable, so a new office was built on the plot instead of the restaurant complex. Completed in 1979, it served as the district headquarters of the Hungarian Socialist Workers Party.35 The overpass leading from the ring road to the Árpád bridge was still not built when a new transport development changed the concept. Since 1970, the Budapest north-south metro line had been under consideration, and the plans involved its reaching the Hungária Ring Road and the Váci Street crossing by 1984. This fact forced the rethinking of the junction arrangement. At first, the traffic engineers intended to route the tramway from the ring road to the Árpád bridge using an overpass; eventually, the overpass created along Váci Street was for cars while the tramline was kept at street level. Due to the underpass network built for the metro station, they could keep the pedestrian connection.

The improved traffic junction, the north-south metro line and the ring road with the tramline radically increased the value of the territory. However, developments started only after the change in the political system after the first multi-party elections in 1989. First, the site at the corner of the ring road was slated for further high-rise construction. The two existing buildings (the trade union and the party headquarters) were assigned to new governmental offices, while new state office structures were planned. However, completion took a long time: the National and Budapest Police Headquarters building was completed in 199736, while the Archives of the City of Budapest, situated behind the police block, were finshed only by 2004.37

The concept of high-rise buildings near the Árpád bridgehead, as first discussed in the urban planning tender of 1957, emerged again in 1992 when the completion of the bridge over the Danube at the southern end of the Hungária Ring became a reality.38 With this realization, completion of the ring road appeared as a viable goal. In parallel with the enthusiasm from the political change and the assumed economic development, heated debates arose over more high-rise buildings along the Hungária Ring Road. As a starting point for the high-rise program, the Árpád bridgehead naturally appeared the best positioned. The former Trade Union Headquarters building was 72 meters high, and though the Police Headquarters’ mass was lower, its antenna tower reached 93 meters. The district and the capital municipality announced an invitational design competition where they “expected building and environmental design concepts that emphasised the importance of the area in the settlement structure.”39 The published six projects all involved high-rise buildings placed at one, two or even each one of the four corners of the Hungária Ring and Váci Street junction. The height of these buildings ranged between 90 and 150 meters. Only one of the price-winning proposals brought forth a differing solution: the architects created an “elevated life space” without high-rise buildings but placing a pedestrian structure at the foliage level. The entries to the 2006 competition reflected the architects’ optimism and the public hope of Budapest’s rapid catching up to the rank of world cities. However, it failed to note that two almost high-rise towers were already under construction at the time of the competition, positioned at the bank of the Danube, on both sides of the Árpád Bridge. These buildings were explained as forming a gate to the district. Due to the previously introduced height limit, they were lower than the former Trade Union Tower: rising only 17 storeys, but extended horizontally, as the real estate developers wanted to regain the cubic meter in the width of the building, which they lost in its height. It is worth mention that neither building won the critics’ approval.40

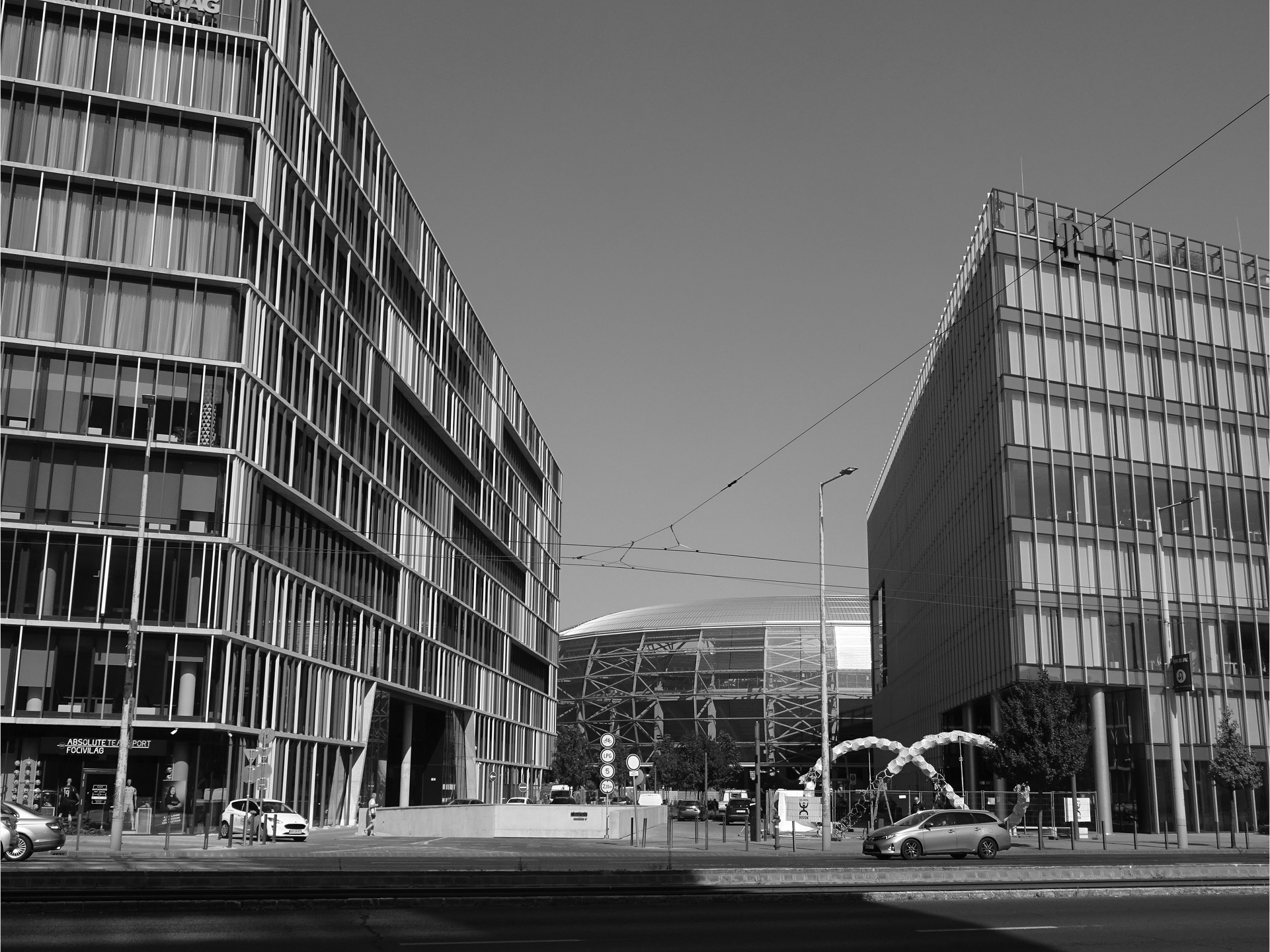

Today, north of the Árpád bridgehead, we find the housing estate built during the 1960s, while to the south are the office buildings built in the 2000s. The last empty building site appeared when the council sold the bus terminal at the corner of Váci Street and Hungária Ring. Though the various development companies and the municipality calculated 90-meter-high towers there, both sides finally accepted the height restriction. The first phase of the project ran between 2017 and 2020. The Agora project currently includes four office buildings – the tallest one has 16 stories – arranged around a deck with greens, benches and a small pool. At the lower levels of the offices, there is a restaurant, a coffee shop, a gym, a newsstand, a pharmacy and a grocery shop.41 Though residents can also use all these services, the employees of the nearby offices are their most frequent users. The deck of the Agora project is connected through a pedestrian underpass to the opposite area, one of more offices but with governmental functions. Today, the territory, especially the Váci Street and Hungária Ring junction, functions as a local office centre, , though in 2016 it was named Árpád Göncz City Centre [Göncz Árpád városközpont], after Hungary’s first post-Communist prime minister.42

The Highway

Urban designers and authorities never gave up the idea that the Hungária Ring Road should be completed as a major traffic artery along its entire length. After World War II, the first new Budapest masterplan appeared in 1949. At that time, the Árpád Bridge was already under construction in the North, and the idea that the planned southern bridge should be built connected to the existing rail bridge also seemed realistic.43 Though this bridge still had not been completed by 1960, the Hungária Ring project was again included in the city’s general layout plan from this year. However, by that time, the function of the road changed, with rising population and the associated traffic growth forcing the road to expand into an expressway, mainly for car and bus transport. As the leading author of the plan described, all the crossings of the ring and the radial roads should be rebuilt as intersection-free junctions. He also mentioned that all the railway barriers within the city should be eliminated.44 It was an ambitious and optimistic plan.

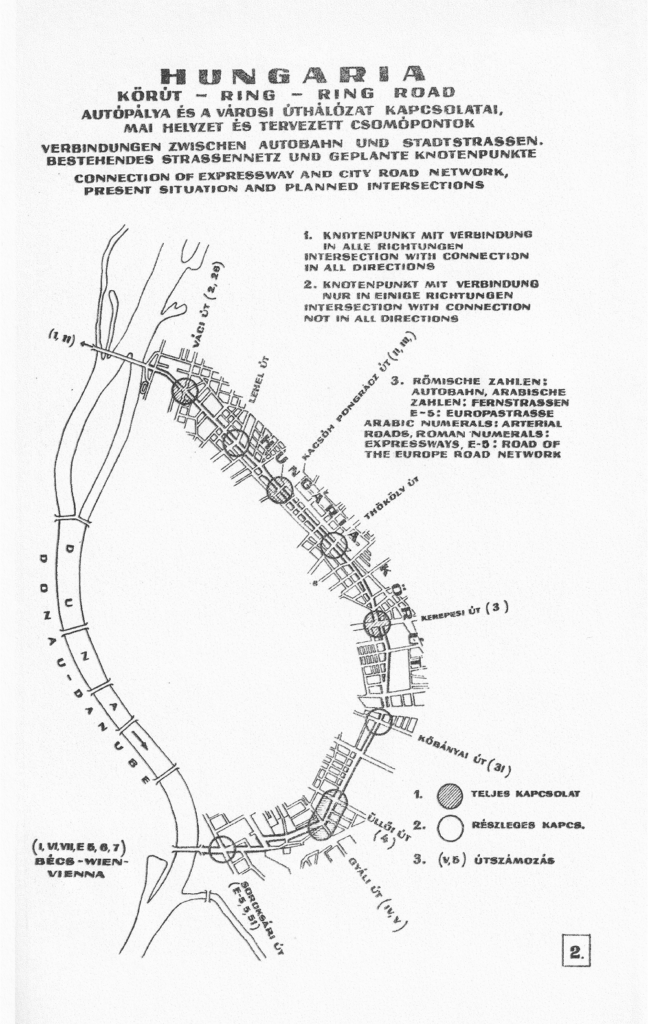

By the middle of the decade, though the southern part of the Hungária Road was still missing, a new concept emerged: how to solve the city’s growing traffic problems. The country’s number of private cars tripled between 1960 and 1965.45 In parallel, the first section of divided highway was handed over in 1965: the M7 from the capitol to Lake Balaton. In this situation, Budapest’s Civil Engineering Company prepared a proposal for the capital to improve Hungária Road in 1966.46 The engineers proposed a triple function for the road: a highway, an expressway and a tramway. “The highways to be built will connect to the Hungária Ring Road and its Buda extension, and at the same time, this road will establish a connection with the city’s road network.”47 The plan proposed building an elevated roadway along the Hungária Ring for the highway function and a ground-level expressway, with public transport provided by the tramline in the middle. All along the ring road, the engineers calculated eight main traffic junctions. Four of them were planned as highway connections, but even in the other cases, the engineers intended to solve the junctions at different levels. In the end, only one of the highway junctions was completed, designed to serve as the arrival of the highway M3 at the Kacsóh Pongrác crossing. Within the same project – as an extension – an overpass was completed, crossing the two railway lines, which had been the main obstacle since the beginning of the idea of the Hungária Ring Road.

The Kacsóh Pongrác junction was completed between 1967 and 1970, and in the next five years, transport and urban planners still assumed the function of the Hungária Ring as a highway within the city. As part of the five-year plan, they also hoped to extend the road to the Danube, including the construction of the southern bridge.48 Yet due to constantly growing motorisation on the one hand and the oil crisis on the other, the latter with a strong impact on the Hungarian economy, the government soon had to rethink the national highway structure. The OMFB (National Technical Development Committee) developed

a new concept for a national highway network, which opted for a highway ring running around Budapest, mainly following its administrative border.49 The Metropolitan Council accepted the new version in 1975: without abandoning the project of widening and fully opening the Hungária Ring, they now assumed it to consist of a motorway with four automotive lanes in both directions and a tramline in the middle. However, due to the north-south metro line, then already under construction, the authorities gave priority to the development of the northern section of the ring road (between the Árpád Bridge and the Kacsóh Pongrác junction).50 These works were planned to be completed by 1986.51 The next phase followed the same road orientation up to the Kerepesi Street junction, where the Budapest Sports Hall was erected in 1982. The planned deadline for this phase was 1989.52

The South Bridge

Though the city prepared the improvement of the Hungária Ring only along two-thirds of its course, after the widening of the Árpád Bridge was completed in 1984, heated discussions started on the southern bridge, referred to as Lágymányosi Bridge for a long time, after the name of the area on the opposite riverbank in Buda.53 Though the bridge and its preference had priority, the Hungária Ring was still incomplete. It was only after Hungary undertook the organisation of EXPO 2005 in Budapest that the completion of the construction work was finally forced through. In fact, the bridge was completed by 1995, although it had only two traffic lanes per direction.54 There was a place left for the tramline in the middle, though still without rails, because the missing phases of the Hungária Ring were not fully developed either. Completion of the whole Hungária Ring Road (including the under- and overpasses) took place in 2000,55 while tram No. 1 was able to complete the road circuit and cross the two bridges leading from Buda to Pest and back to Buda only in 2015. The completion of the road radically changed the urban function: the whole built environment of this new section, leading from the Üllői Road to the former Lágymányosi, now Rákóczi Bridge, was developed mainly in a single impulse of the 1990s. Only a few buildings are left from the past. Walking along the street, we pass a bus station, a business centre, a sports hall, offices, car dealerships, and empty plots. We hardly see any pedestrians on the streets because the parking places are underground or behind the buildings. Completing the picture of the automotive landscape are the car dealerships and shopping centres lining the road toward the bridgehead.

Conclusion

Tram No. 1 crosses the Hungária Ring in a 50-minute span from one bridge to the other. The traveller’s impressions vary greatly, closely depending on the period when the surrounding environment was formed. When the idea of the Hungária Ring Road was born, the architects and urban planners imagined a traditional 19th-century urban structure consisting of boulevards and avenues. Placed at the very outskirts of the city, the designated line of the Hungária Ring followed this outer periphery, with its main core sited parallel to the City Park and sided with holiday homes. Even now, we find a few villas that survive, due to their small plots. In the section leading up to the People’s Park, the ring has still managed to retain traces of its promenade character. A few turn-of-the-century public buildings were settled along with the green environment, since as the ring road spread out from the middle in both directions, it offered large, still unbuilt plots for the preferred pavilion layout of such facilities as military barracks and hospitals. As settlement expanded, apartment buildings and non-polluting factories similarly arose.

The city of Budapest never gave up the idea of developing the Hungária Road into a ring road leading from the Danube to the Danube. Urban concepts changed over time, though not only shifting fashions in urban design necessitated these changes. At the Árpád bridgehead, a housing estate was planned, with adequate space and vegetation. However, the junction of the Hungária Road and the radial Váci Street soon became not a public but a political centre: a perfect location for state institutions due to the excellent traffic position. After the political changes of 1989, the area attracted more private offices. Their immediate environment has an international flavour: green vegetation and a shallow pool, cooling the air in the summer heat between the offices. We find cheap shops and bakeries only in the underpass leading to the subway station, as well as homeless people.

Though the capital never realised the elevated highway over the Hungária Road, the motorway with the tramline attracts heavy traffic. When taking the tram, we experience the architecture of 120 years within a 50-minute journey. Travelling towards Buda, near the Danube, a vast building appears on the right, below the road. It is the MÜPA cultural centre, which includes the Béla Bartók National Concert Hall, the Ludwig Museum, and the Festival Theatre concert hall. Unfortunately, the tram door has closed, so getting off and walking down to the complex is no longer possible – hopefully, next time, walking on foot.

KROPF, Karl. 2017. The

Handbook of Urban Morphology.

Chichester: John Wiley & Sons,

248 p.

Official report of the Met-

ropolitan Public Works Council

on its activity in 1870 and 1871;

Annex of the Budapesti Közlöny,

25 April 1872, p. 114.

A detailed analysis concerning

the three entries’ urban concepts

is presented in PREISICH, Gábor.

2004. Budapest városépítésének

története: Buda visszavételétől a II.

világháború végéig. Budapest: Terc,

pp. 138–156.

The architect was Frigyes

Feszl.

A Hon, 5 October 1872, p. 2.

PREISICH, Gábor. 1979.

A körutak jelentősége Bécs

és Budapest számára. Műem-

lékvédelem, 23(2), pp. 141–145.

The tunnel crossed two

railway lines, so it was long, but

was rather narrow with its 2.85 m

width; Magyar Mérnök és Építész

Egylet közlönye, 1875, 9(4), p. 195.

Pesti Napló, 17 February

1883, p. 2.

The Hungarian Royal

Mental Hospital was completed

between 1880–1884, by architect

Antal Wéber. In: MARÓTZY,

Katalin. 2009. Wéber Antal

építészete a magyar historizmus-

ban. Budapest: Terc, pp. 108–110.

Budapesti cím és lakjegyzék,

1881, p. 2.

Az Építési Ipar, 1883, 7(18),

p. 162.

Nemzet, 23 January 1887, p. 3.

KÖRNER, Zsuzsa. 2004.

A telepszerű lakásépítés története

Magyarországon 1850–1945.

Budapest: Terc, p. 179.

Nemzet, 28 January 1888, p. 3.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 29 May

1891, p. 5.

A Hon, 5 October 1872, p. 2.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 9 January

1894, p. 6.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 23 July

1895, p. 7.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 16 January

1894, pp. 1–2.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 19 June

1894, p. 3.

VADAS, Ferenc. 2010. MTA

Állatorvos-tudományi Kutatóintézet.

In: Épített örökség a magyar

tudomány szolgálatában.

Budapest: Magyar Tudományos

Akadémia, pp. 132–135.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 7 July

1899, p. 7; The school com-

plex was designed and built by

Sándor Baumgarten, Sándor and

Herczeg, Zsigmond between 1899

and 1904.

Fővárosi Közlöny, 10 April

1900, p. 473.

Law No XVIII of 1908 on

the development of the capital

city of Budapest.

Fővárosi Közlöny,

18 December 1936, p. 1912.

Fővárosi Közlöny. 1937.

Új utcaelnevezések. Fővárosi

Közlöny, 22 October 1937, pp.

1795–1796. In addition to the

official name to this day, the

common language still uses the

name Hungária Ring or Ring

Road. I will also prefer this from

now on.

Vállalkozók Lapja,

17 November 1938, p. 4.

ZÖLDY, Emil. 1947. Az

Árpád-híd pesti hídfőjének és

környékének rendezése. Tér és

Forma, 20(10), pp. 215–218.

Világosság, 23 April 1949, p. 2.

Appendix of the daily

Szabad Nép, 27 August 1950.

The public part of the building

changed its profile and is used as

a theatre till now.

MERFY, István. 1950.

A Sztálin híd két hídfője körül.

Világosság, 27 April, p. 2.

GRANASZTÓI, Pál. 1957.

A budapesti Árpád-híd pesti híd-

főjének városrendezési tervpályá-

zata. Magyar Építőművészet,

6(5–6), pp. 126–132.

DUL, Dezső. 1970. Szaksze-

rvezeti nyomda és irodaház. Mag-

yar Építőipar, 19(9), pp. 532–536;

DUL, Dezső. 1976. A magasházak

tervezési és szerkezeti problémái

a SZOT Budapest, Váci úti

irodaházával. Magyar Építőipar,

25(3), pp. 132–137.

Magyar Építőművészet.

1972. Korszerű vendéglátóipari

együttes tervpályázata. Magyar

Építőművészet, 21(6), pp. 2–8.

Magyar Építőművészet.

1980. Budapest, XIII. kerületi

MSZMP székház. Magyar

Építőművészet, 29(2), pp. 46–49.

FINTA, József. 1996.

Rendőrségi székház, Buda-

pest – az ORFK, BRFK, TOP új

irodaháza. Magyar Építőipar,

46(1), pp. 6–10.

KÉSZMAN, József. 2004.

Ninive örökösei. Budapest

Főváros Levéltárának új épülete.

Régi-új Magyar Építőművészet,

2(4), pp. 3–7.

FINTA, József. 1992. Az

ORFK – BRFK és az Országos

Tűzoltó Parancsnokság új

székháza, Budapest. Magyar

Építőipar, 42(10–11), pp. 356–357.

BUGYA, Brigitta. 2006.

Angyalföldi csomópont.

Városépítészeti tervpályázat.

Régi-új Magyar Építőművészet,

4(5), pp. 26–27.

PRAKFALVI, Endre. 2005.

Welcome to the future: Két

torony az Árpád hídnál. Régi-új

Magyar Építőművészet, 3(6), pp.

36–38; VARGHA, Mihály. 2006.

Roncsoló derbi. Budapest, 29(4),

pp. 28–29.

HB REAVIS. 2024. Agora

Budapest [online]. Available at:

https://www.agorabudapest.com/

(Accessed: 2 November 2024).

Árpád Göncz (1922–2015),

President of the Republic of

Hungary 1990–2000.

Új Építészet. 1948.

Nagy-Budapest általános ren-

dezési terve. Új Építészet, 3(8),

pp. 279–296.

PERÉNYI, Imre. 1961.

Budapest és környékének általános

városrendezési terve a nagyvárosok

fejlesztési problémáinak tükrében.

Településtudományi közlemények,

13, pp. 3–16.

The number of private cars

in the country was 31,268 in 1960,

while it grew up to 99,395 by 1965.

See: KSH. 2024. Szállitás (1960–)

[online]. Available at: https://

www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xstadat/

xstadat_hosszu/h_odme001.html

(Accessed: 2 November 2024).

A Hungária körút fejlesz-

tése. 1966. Tanulmányok Buda-

pest közlekedéséről. 3. Füzet.

Budapest Főváros Tanácsának

Végrehajtó Bizottsága.

A Hungária körút fejlesz-

tése. 1966. Tanulmányok Buda-

pest közlekedéséről. 3. Füzet.

Budapest Főváros Tanácsának

Végrehajtó Bizottsága, p. 2.

GYŐRFFY, Lajos. 1971.

Budapest és környéke általános

városrendezési terve III. Útháló-

zat és közúti létesítmények. Buda-

pest, 9(1), pp. 7–9; Lajos Győrffy

was the department head at the

Budapest City Planning Company.

A közúti közlekedés infra-

struktúrája. 1973. Budapest:

Országos Műszaki Felügyelőség.

Hungária körút beruházási

programja. 1983. Budapest Főváros

Tanácsa Végrehajtó Bizottságának

Közlekedési Főigazgatósága.

Hungária körút beruházá-

si programja. 1983. Budapest

Főváros Tanácsa Végrehajtó

Bizottságának Közlekedési Fői-

gazgatósága, p. 4.

Hungária körút beruházá-

si programja. 1983. Budapest

Főváros Tanácsa Végrehajtó

Bizottságának Közlekedési Fői-

gazgatósága, p. 9.

The Lágymányosi Bridge was

renamed for Rákóczi Bridge in 2011.

SCHULEK, János. 1992.

A lágymányosi Duna-híd és

kapcsolódó úthálózata. Magyar

Építőipar, 42(3–4), pp. 74–76.

FÁBIÁN, András, RÉKASI,

József and VARGA, Csaba. 2001.

A Hungária körúti körgyűrű és

az 1-es villamospálya kiépítése

Budapesten. Közúti és Mélyépíté-

si Szemle, 51(6), pp. 231–238.

DOI: https://architektura-urbanizmus.sk/2025/03/19/the-hungaria-ring-road-of-budapest/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License