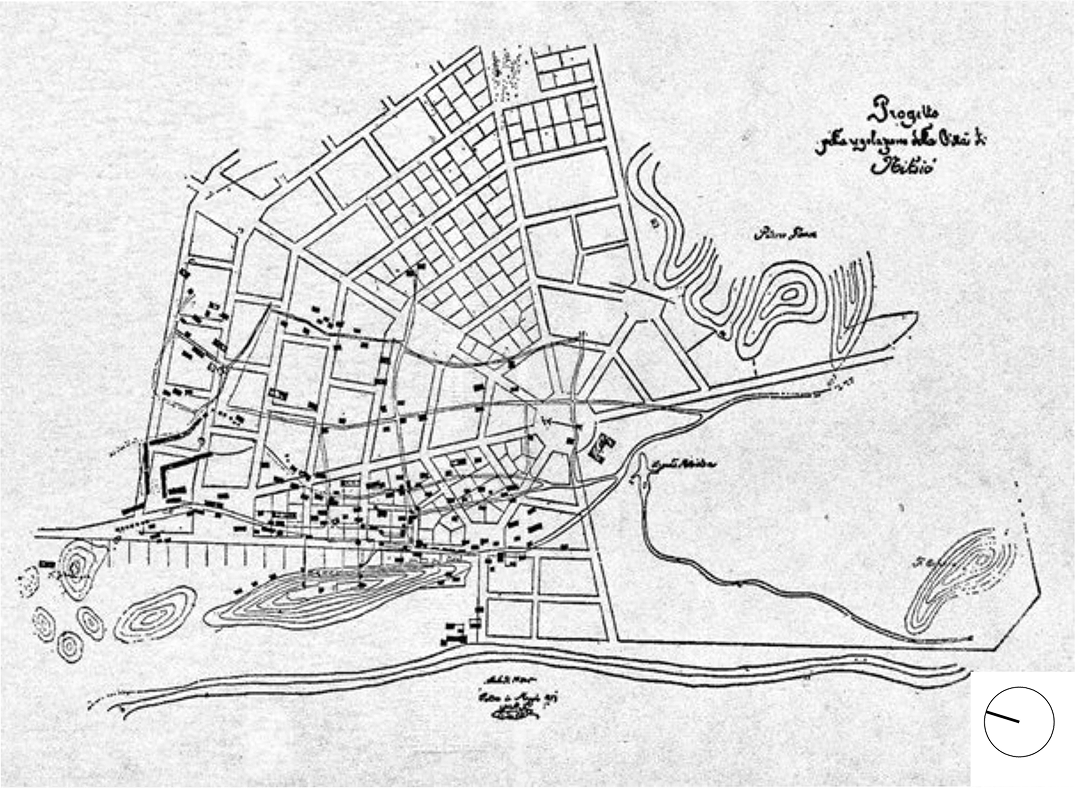

After liberation from the Ottoman Empire in 1877, Nikšić became part of Montenegro, a sovereign and internationally recognized state after the Berlin Congress in 1878 became. With the permission of the Austro-Hungarian authorities, Croatian architect Josip Šilović Slade (1828–1911) was invited by Prince Nikola Petrović (1841–1924) to Montenegro, where he designed a series of significant buildings and infrastructure facilities. One of his most important achievements is the First Regulatory Plan of the City of Nikšić, created in 1883, which draws its roots from the large-scale reconstruction of European cities in the late 19th century.

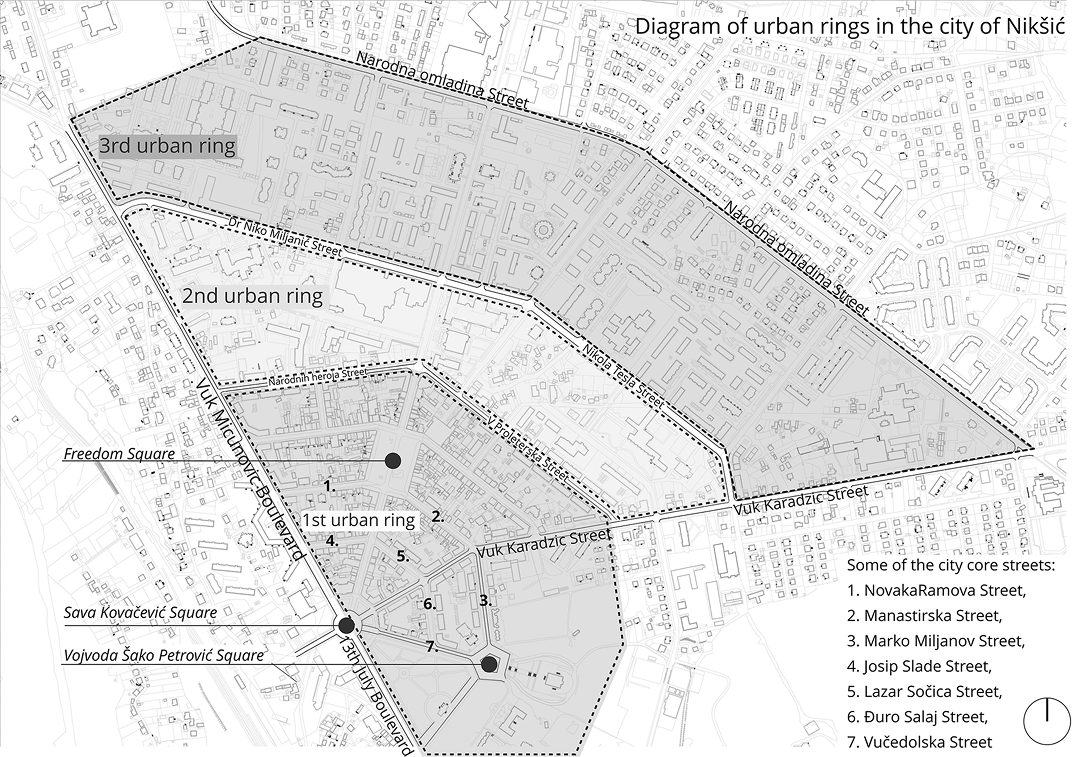

The first regulatory plan of Nikšić was modeled after ideal Renaissance cities, with a clear geometric layout consisting of five squares and an interconnected system of streets. From the central city square, seven primary streets extend in all directions. These primary streets are connected by secondary streets, forming a radial urban matrix that allowed for the city’s development in concentric urban rings. The main focus of this paper is the urban matrix of Nikšić, a rare typological example of radial city organization.

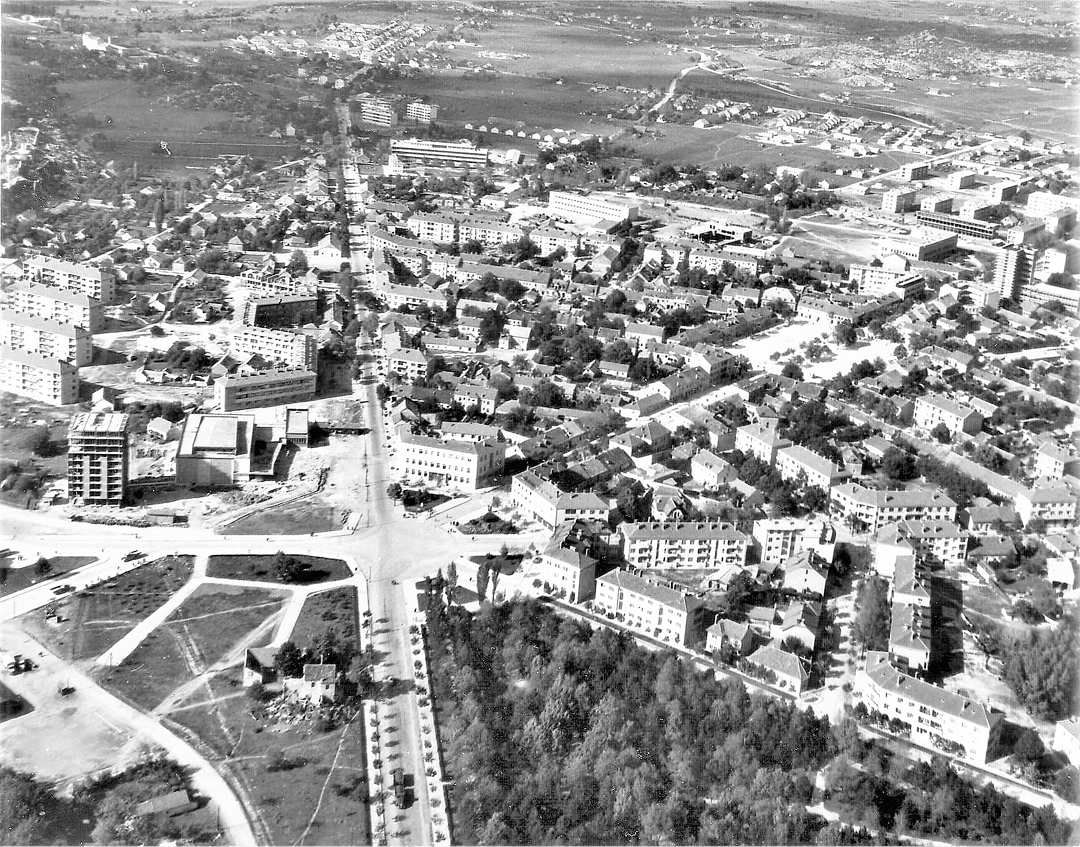

From the end of the 19th century until the mid-20th century, Nikšić’s growth was slow. After World War II, when Montenegro became part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Nikšić experienced rapid urbanization, becoming one of the most rapidly expanding cities in the region. This period of industrialization led to the development of new urban plans which, thanks to the existing urban matrix, were able in turn to define additional urban rings. Today, Nikšić’s urban composition consists of several rings: the city core, public buildings, multi-apartment housing, and individual housing.

The primary aim of this paper is to explore the urban transformation of Nikšić, focusing on the formation of distinct urban rings that have contributed to the unique urban and architectural identity of the city.

Introduction

When discussing the development of settlements in Montenegro, it is important to consider several factors that predominantly influenced their degree of development. Historical circumstances did not allow towns in Montenegro to develop with the same dynamics and in the same manner as in other European countries during any observed time period. In every aspect, historical circumstances, most notably the continuous struggles for liberation and the inability to develop the economy, caused urban settlements to remain undeveloped.

The key aspects of this study are delineated through the methodological framework of the research, the definition of the concept of urban rings in the city of Nikšić as the central focus of the research, as well as the examination and analysis of urban development in Montenegrin cities, with particular emphasis on Nikšić, through the influence of urban planning documentation on the development of urban areas (or rings), as well as the general plan of the city and the documentation on territorial planning. The mentioned urban documentation is arranged to provide a chronological description of the genesis of the city and lead us towards better and more responsible management decisions.

Methodological Framework

This research is designed as a qualitative study, focused on the analysis of the phenomenon of ring-road transport infrastructure within the urban matrix of Nikšić, Montenegro, diagnosing matrix of urban development by an indicator system, analysis and methods.

The primary aim of the study was to identify the key factors that influenced the formation of urban rings over different historical periods, as well as to analyse their specific spatial and functional characteristics.

For the purposes of this research, secondary source analysis and spatial-planning analysis were employed to ensure the collection of relevant and reliable data:

- Historical-analytical method – Data on the historical, political, social, and economic conditions under which cities in Montenegro developed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries were collected and analysed, with a particular focus on the city of Nikšić.

- Analysis of spatial planning documentation – Key urban planning documents of the city were examined in detail, specifically: the first regulatory plan from 1883, which represents the initial urban framework and the core of the city, urban planning documents from the post-World War II period, which facilitated the expansion of the urban matrix and the formation of new urban rings.

- Analysis of indicators of urban transformation – The study also involved the analysis of significant architectural structures and their interrelationships, as well as the analysis of the relationships between different urban rings, which provided insights into the evolution of urban zones over time.

The collected data were analysed using thematic and comparative analysis, which allowed for the precise identification of the forms and characteristics of the urban rings. Thematic analysis focused on identifying the specific identifying traits of the observed rings. It was determined that three main rings can be confirmed in Nikšić:

- The first ring: the central core of the city, with the oldest urban characteristics.

- The second and third rings: formed as a result of the gradual expansion of the city through the implementation of new urban plans.

Comparative analysis focused on spatial characteristics and comparison of the architectural structures within each ring, enabling the examination of spatial continuity and the evolutionary development of the city of Nikšić.

The Concept of Urban Rings in the City of Nikšić

Observing the current urban morphology of the city of Nikšić, the noticeable trait is a diversity of urban forms, consisting of a combination of linear, orthogonal, and radial layouts of the city’s urban blocks. However, it is visibly evident that the city developed concentrically, starting from the urban core that developed according to the first regulatory plan, with sporadic interpolation of individual buildings, mainly after World War II.

The term urban rings, as used in this work, refers to the concentric development layers of the city, each with distinct characteristics and functions. However, it is important to clarify that in the case of Nikšić, these “rings” are not synonymous with districts but instead represent specific urban zones defined by their spatial and functional attributes.

The First Urban Ring

In this context, the old urban core of the city can be considered the first urban ring. This urban ring developed specific spatial characteristics resulting from the synthesis of the urban layout of streets, urban blocks, and unique architecture, forming a distinct urban identity. It should be noted that, in a morphological sense, the urban rings in the city of Nikšić have a limited radial form, as the streets that delimit them are not continuously radial but linear and intersect at certain angles. Also, the city was not developed fully to match the original regulatory plan, which envisaged the expansion of the city in concentric directions relative to the centre. The centre of this urban ring, as well as all subsequent ones, is located in the centre of the roundabout at Save Kovačević Square.

Two significant city roadways converge and diverge from Save Kovačević Square. From the southwest direction, Boulevard 13th July converges into the square, while Boulevard Vuk Mićunović diverges from the square and extends northwest. These roads mark the boundary between the linear layouts of the city’s urban blocks and the part of the city that developed within urban rings according to the first regulatory plan and post-war urban plans. On one side, these two boulevards form the boundary, while on the other side, the boundary of the urban rings is represented by Vuk Karadžić Street, which starts from the centre of Save Kovačević Square and extends northeast.

The Second Urban Ring

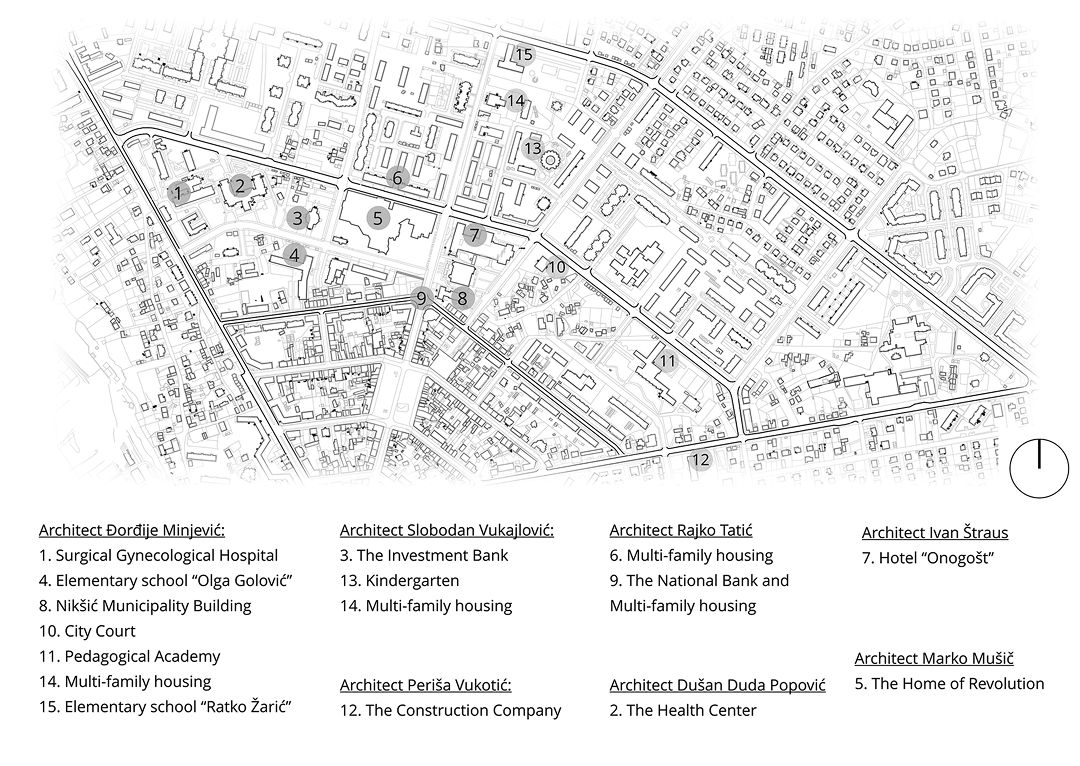

The second urban ring stretches from Boulevard Vuk Mićunović to Vuk Karadžić Street. On the southern side, it borders the first urban ring via Narodnih Heroja Street and 5. Proleterska Brigada Street [Pete Proleterske Brigade]. On the northern side, this urban ring borders the third, via Dr. Niko Miljanić Street and Nikola Tesla Street. The main characteristic of this urban ring is the distribution of facilities of significance to the city, which are provided in the form of public buildings such as a hospital, city hotel, bank, court, faculty, and student dormitory, designed by some of the most prominent Montenegrin and Yugoslav architects of the 20th century.

The Third Urban Ring

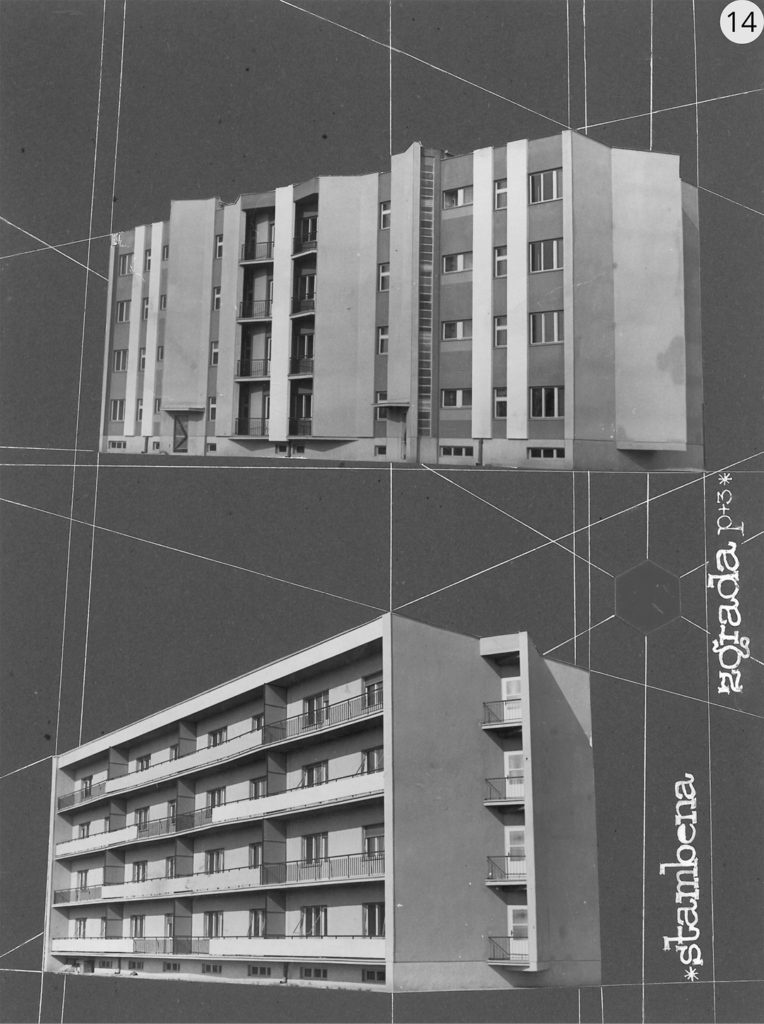

The third urban ring is bordered on the south by the second urban ring via Dr. Niko Miljanić Street and Nikola Tesla Street. On the northern side, it is bounded by Narodna Omladina Street. This ring also stretches from Boulevard Vuk Mićunović to Vuk Karadžić Street. The third urban ring is designated for multi-family housing, which is provided through buildings of various typologies. This ring also includes kindergartens and primary schools. Beyond the third urban ring lies the zone of individual detached housing.

In summary, the urban rings in Nikšić illustrate the city’s concentric development, with each ring representing a different phase of urban growth and serving various functions within the urban matrix. It is important to note that these rings are defined by the streets that surround them, such as Josip Slade Street, Lazar Sočica Street, Đuro Salaj Street, Novak Ramov Street, Manastirska Street and Marko Miljanov Street, which exhibit certain ring characteristics.

The development of these urban rings and their key characteristics can be observed through the genesis of the city of Nikšić and the implementation of urban plans.

The Historical and Political Context of Urban Development of Montenegrin Cities at the End of the 19th and the Beginning of the 20th Century

In the development of Montenegrin urban settlements, we distinguish two stages: stagnant and dynamic. The stagnant stage encompasses the centuries-long Ottoman presence and the struggle for liberation from it. The more dynamic stage includes the period after 1878, marked by the Berlin Congress, which is traditionally considered the chronological turning point for the observable urban development of settlements in Montenegro.1

In the first half of the 20th century, Montenegro, whether as an independent state or later as part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, remained an underdeveloped area. The Balkan Wars and then the First World War affected the fragile economy. Although the period between the two world wars was somewhat favourable for the country’s development, Montenegro remained underdeveloped and insufficiently urbanized. Urban settlements in Montenegro still could not be called cities in the true sense of the word; they were towns and small towns.2

After World War II, there was a change in the political and social system, and Yugoslavia became a socialist federation (in which Montenegro was first called the People’s Republic of Montenegro, and later the Socialist Republic of Montenegro). Due to the different levels of economic development among the republics, one of the main goals of socialist governance was to ensure balanced economic and social development of all areas. This goal resulted in rapid economic development of the less developed republics, especially Montenegro. Economic development also influenced the urban development of settlements, which can best be observed through the degree of urbanization.

There are two periods in which we can observe the shifts of the urbanization level in Yugoslavia: the period from 1921 to 1953 and the period after 1953. The urbanization level is expressed by the urbanization coefficient, which represents the percentage of urban population in the total population. If the urbanization coefficient ranges from 0–20, we speak of low urbanization. The urban population in Montenegro in 1921 was only 6.5%, and in 1953 it was 10.2%.3

According to the 1971 census data, the urbanization rate in Montenegro increased almost threefold to 29.5%. The greatest impact on urbanization in the post-war period was the economic, particularly industrial, development.4

Another pivotal moment in the context of urbanization and the development of urban settlements is certainly the end of World War II and the post-war economic development of socialist Yugoslavia. The period from the Berlin Congress to the end of World War II witnessed Montenegro, despite its first regulatory plans, undergoing only slow urbanization due to its small economic base and lack of skilled personnel. After World War II, rapid industrialization led to dramatic urbanization of the country, accompanied by urban planning.

The development of Montenegrin cities largely depended on historical and political circumstances that dictated economic development, which in turn influenced both urbanization and the construction of cities. Through the aforementioned aspects, it is possible to examine the urban development of the city of Nikšić, with particular focus on urban planning documents and the formation of urban rings as their specific manifestation.

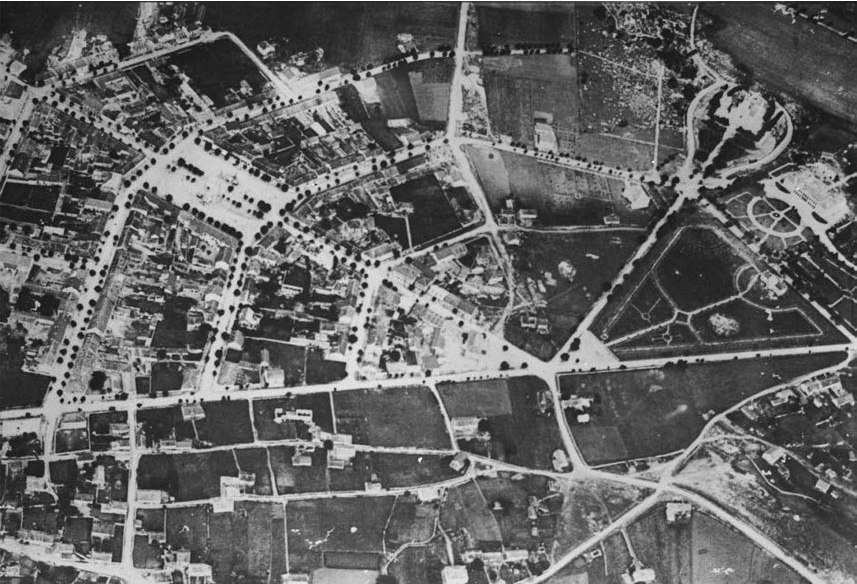

Urbanization of Nikšić from the Late 19th Century to the End of World War II

In the genesis of the city of Nikšić, the year 1877, marking the end of Ottoman rule, can be considered the beginning of the city’s modern development. Unquestionably, the key role in modernizing the city was played by the First Regulatory Plan of the city from 1883, created by architect Josip Šilović Slade (1828–1911). The urban scheme, which represents a combination of the ideal Renaissance city with certain Baroque principles, provided precise guidelines for the development and construction of the city.

However, the process of building the city progressed quite slowly for several reasons. The first reason was economic. Montenegro, after constant warfare for its national liberation, was quite impoverished. Hunger, disease, and poverty were the most urgent threats, hence the mere survival of the population was a higher priority than the construction of new buildings and infrastructure. Finally, the lack of an educated workforce affected the speed of modernization, specifically the speed of city construction.

The period after liberation is characterized by significant changes in the structure and life of the city. In addition to the physical changes in the city, which are reflected in adopting the morphology envisaged by the first regulatory plan, there were also demographic and cultural changes.

Before liberation, Nikšić had about 2,500 inhabitants. After the liberation in 1877, significant changes occurred in the population, reflected in the mass emigration of Muslim families, who until then constituted the majority of the population. Of the 410 Muslim households that dwelled there before the war, by 1882 there were only 19 still remaining in Nikšić.5

Although the Orthodox Christian population began to settle in Nikšić, a certain number also left the city due to poverty and hardship. According to one statistical finding, Nikšić had 1,976 inhabitants as a result of these migrations, which clearly indicates that the population declined compared to the period before liberation.6

Clearly, considering its small population and unfavourable economic conditions, much time was needed for the city to start developing in terms of physical construction and infrastructure. In the period after liberation until the end of World War II, modest industrialization began. These were small-capacity factories whose production mainly met local needs. The first guild associations also emerged, with the First Nikšić Craft Association being formed in 1906, and the Industrial-Shareholding Association being established in 1908.7

The general conclusion is that Nikšić, in the period from 1877 to the end of World War II, was not a city in the true sense of the word, but rather functioned as a commercial and economic centre of this part of Montenegro. Nikšić was a small town whose existence was based on the income from agriculture, trade and craftsmanship.

Formation of the First Urban Ring through the First Regulatory Plan of the City (1883)

A few years after 1877, the city largely retained the same appearance it had during the Ottoman period. New residents from various parts of Montenegro began to settle in Nikšić, creating a need for new houses, territorial expansion, and new city organization. At the suggestion of the citizens to designate a place for the construction of the new town, Prince Nikola came to Nikšić in the spring of 1884 and brought the plan for the New Town, which had been created the previous year by Josip Šilović Slade. At that time, Slade was one of the most engaged architects in Montenegro. With the permission of the Austro-Hungarian authorities, Slade, who was from Dalmatia (then a province of Austro-Hungary), accepted the invitation from Prince Nikola. The plan by Josip Slade from 1883 served as the foundation and basis for the development of the modern city of Nikšić.

On the open, spacious field east of the Turkish casaba, surrounded by rivers and wooded hills, Slade had an ideal opportunity to realize the regulatory plan for the new city. The plan featured simple, clear forms, open to the sun and nature, providing optimal living and working conditions for the anticipated future population of approximately 10,000 inhabitants.8

With the street development system, it was entirely possible to expand the city several times with appropriate modifications while maintaining a modern city in terms of organization and traffic. This enlargement potential is certainly aided by the initial organization and urban matrix of the city, which spreads seamlessly across the terrain.

The core of the future city consisted of a large quadrangular square and four smaller ones in other areas, connected by wide straight streets radiating outwards. The plan included the construction of green spaces, necessary city infrastructure, sewage and water supply systems, as well as the peripheral construction of single-story and two-story buildings.9

As the population grew and the economy improved, further development and construction in Nikšić became necessary, leading to the opening of new streets and a small square. Fourteen streets and the eastern circular square were built, either completely or partially, bordered by the cathedral, the prince’s new palace, the church building (the consistory), the cemetery, and green areas. Additionally, two new streets connected the square with the city centre and the carriage road towards Podgorica. In a very short time, as the city developed and expanded, the concept of the regulatory plan began to be fulfilled exactly as architect Slade had envisioned.

The regulatory plan envisaged a total of five squares, one octagonal, one pentagonal, and three rectangular. Only three squares from this plan were eventually built. The central square, which was created at the start of construction of the new town, is rectangular in shape and has retained the same shape to this day. Today, this first square is called Freedom Square [Trg Slobode].

Situated 180 meters to the southwest, there is a second octagonal square, also realized according to Slade’s plan, now called Save Kovačević Square. The third pentagonal square is located in front of the Cathedral Church and is called Vojvoda Šako Petrović Square. In these squares, Slade aimed to achieve new visual effects with a stronger emphasis on the main monumental building. The result is the enhancement and magnification of aesthetic effects when approaching and viewing the main and central building (the Cathedral Church and Prince Nikola’s Palace).

To realize the idea of an ideal city, which Slade presented only schematically, would have been very difficult even for much wealthier and more organized countries than Montenegro, war-torn and deeply impoverished. It was a true feat that it was even carried out. Behind this had to stand the monarch, the army, and the people. The construction was carried out without mechanization, practically with bare hands and without detailed plans and projects. The unique case of the construction of Nikšić, both in terms of the type chosen and the time and manner of execution, deserves further study.

Elements of the Spatial Identity of the Urban Core of Nikšić

The urban core of Nikšić, considered as the first urban ring of the city, has developed a distinct spatial and urban identity over time. Among the most significant elements that have formed this identity are:

- morphology of the urban core and public spaces,

- architecture of the townhouses,

- architecture of significant landmark buildings.

Morphology of the Urban Core and Public Spaces

The morphology of the urban core of Nikšić is predominantly determined by the network of streets, city squares, and the city park. Streets, as a basic element of spatial identity, crucially influence the formation of the city’s image and its identity. Depending on the space they form, two types of streets can be observed.

The first type of street creates a sense of enclosure, similar to a room, courtyard, or square. Buildings and streets are inseparable and interdependent elements of the urban fabric, creating enclosed spaces with a specific atmosphere. This type of street is usually associated with settlements and cities formed before modern urbanism, and can be applied to all the streets of the narrower urban core: Marko Miljanov Street, Manastirska Street, Novak Ramov Street, Josip Slade Street, Lazar Sočica Street, Njegoševa Street, and Ivan Milutinović Street.

The second type of street features free-standing buildings and structures that lack a strong connection with their surroundings, resulting in a disrupted sense of spatial continuity. This street design is often linked to modern urbanism principles. Positive examples of such streets include Vuk Mićunović Boulevard and Vučedolska Street.

In addition to streets and the city park, the public spaces of the urban core of Nikšić also include three squares: Save Kovačević Square, Vojvoda Šako Petrović Square, and the largest city square, Freedom Square. These squares are connected by a network of streets, creating a unique urban composition as envisaged by the first regulatory plan.

A park, as a human creation with aesthetic qualities derived from the appropriate use of materials and the use of composition as a design method, can be viewed as an artificial space just like a city. The city park in Nikšić is a good example of the polyvalence of urbanism and architecture composition, because the city park extends to the edge of Sava Kovačević Square, an “extension” that appears neither forced nor pretentious. As a result, Sava Kovačević Square can also be viewed as a park square. The example of park squares demonstrates the unity and indivisibility of urbanism from park architecture, as well as the mutual complementarity and interweaving of ideas and forms.10

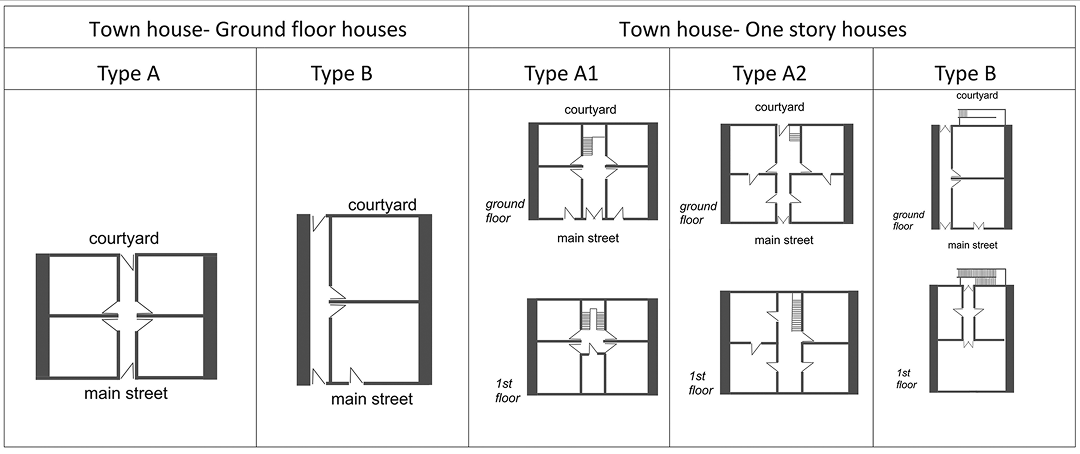

Architecture of the Townhouses

Architecture in the urban core of Nikšić mainly refers to typical single-family townhouses. These urban houses have a clear concept expressed through a simple form, restrained openings, and the use of materials. Townhouses were usually built at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. We distinguish between single-story and two-story houses.

Since these houses were made of stone, the facade treatment distinguishes between those with visible jointed stone and those that were plastered. The facades were usually painted white or in a light pastel colour, with fenestration were made of high-quality wood. Wealthier houses had specific ornamentation related to the treatment of window frames, lintels, and most often balconies and balcony railings.

The beginning of the construction of the new town in Nikšić attracted a large number of masons and other craftsmen from Herzegovina, Boka, Dalmatia, and Italy, who despite the absence of professional designers, limited financial resources, and time, were able to recognize the needs of future owners.

The buildings are simple, modest, and closely resemble each other. On the ground floor of the single-story houses, there were shops and a side passage through which a horse loaded with agricultural products and firewood could pass. In single-story houses, there were also shops with cramped rear sections for goods or living, or just apartments.

Architecture of significant landmark buildings

Prominent architecture in the urban core of Nikšić refers to buildings for purposes of culture, various state organizations, and associations, often with notable visual prominence due to their ornamentation and the design of their details of windows, balconies, railings, and doors. There are also residential buildings of some wealthy families who, in accordance with their status at the time, erected larger structures. Here, special attention is given to the entrance doors, which are usually made of high-quality, carved oak. Above the doors of wealthier families, there was a balcony with a richly decorated railing, which also served as a canopy and protection from rain or snow during winter.

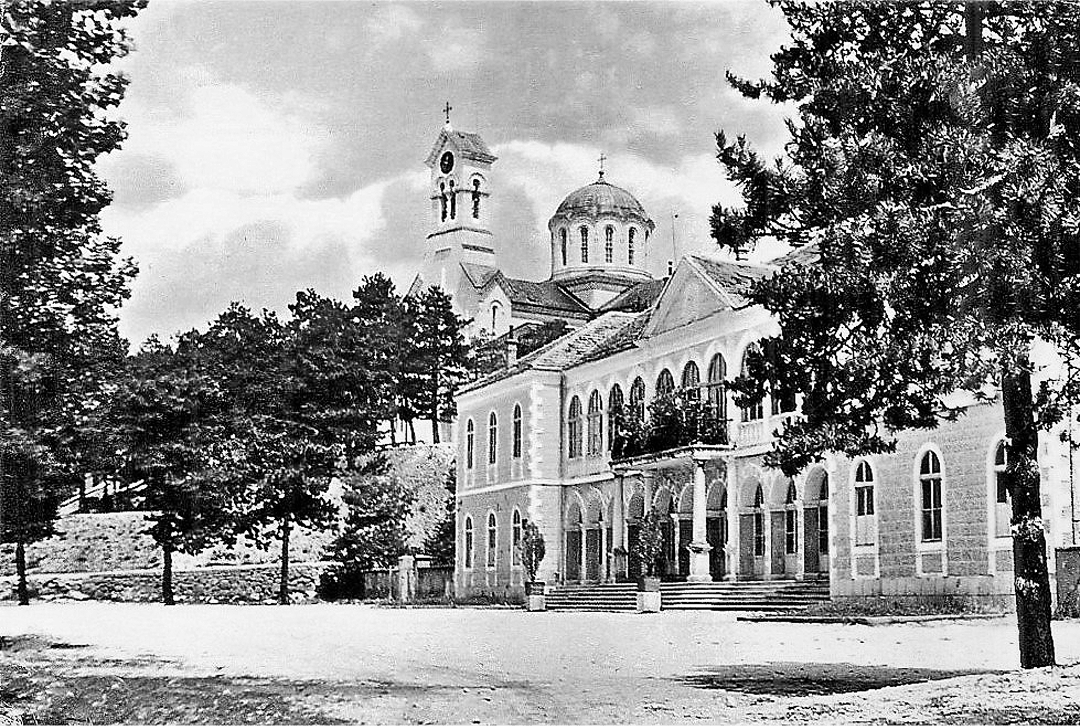

Among the visual and symbolic elements, the most significant is unquestionably the cathedral church dedicated to St. Basil of Ostrog, designed by the Russian architect Mikhail Timofeevich Preobrazhensky (1854–1930) in 1891 at the request of Prince Nikola. In the immediate vicinity of the cathedral church is King Nikola’s Palace, built in 1900 according to the design of Josip Slade.

Perhaps the most pronounced form of the city’s physical structure is the urban silhouette, forming its most visible representation, and as such, a particularly significant part of the urban image and spatial identity. The silhouette of the city’s physical structure is primarily an expression of a series of individual and visually dominant elements, which combine with the terrain morphology in each given example of the city. The focal central units, grouped or individually distributed across the terrain of the agglomeration, give the macro-shape of the urban fabric, the silhouette.11

The Cathedral Church significantly contributes to the silhouette of the urban core, serving in a way as its spatial symbol and a key point in the urban silhouette of this part of the city.

Construction of the Second and Third Urban Rings of Nikšić through Urban Planning after World War II

Thanks to the socialist system, which required balanced economic and industrial growth across all regions of the country, Montenegro had a particularly favourable opportunity after 1945. Nikšić emerged as the city that would spearhead the industrial development of the republic, due both to its geographic location and its natural resources.

After the war, Montenegro focused on rebuilding its cities: severely damaged buildings were demolished and replaced, while minor damage was repaired. As after the Berlin Congress, a lack of skilled professionals slowed reconstruction efforts post-World War II. Urban planning and architecture departments were underdeveloped, lacking trained architects and engineers. Montenegrin architects, mostly educated in Zagreb or Belgrade, primarily worked on public buildings, while complex urban plans were often handled by experts from more developed regions like Belgrade and Zagreb, especially noticeable in Nikšić.

The initial urban plans created by experts from outside Montenegro generally lacked precise guidelines for future development, lacked thorough programmatic elaboration, and failed to assume a regional perspective on the development concept of the area.12

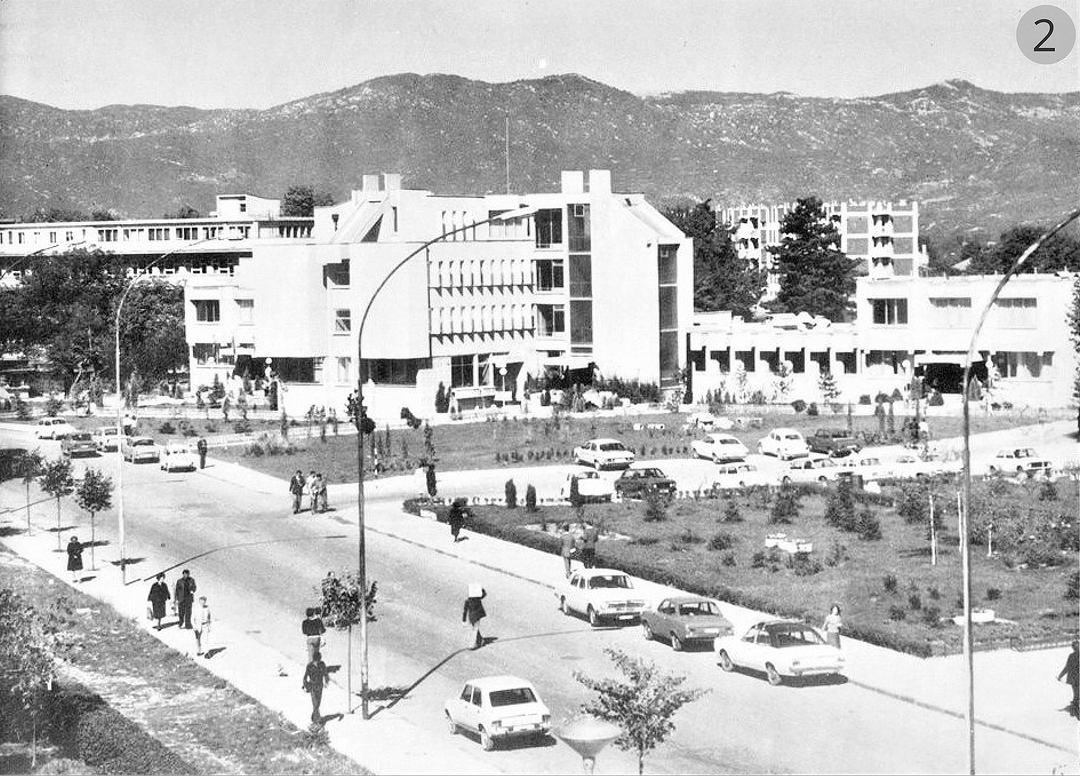

Heavily damaged, Montenegrin cities now largely lost their original appearance, creating a contrast between modernist layouts and remnants of earlier construction. In some cases, this contrast is sharp, while in others, a continuity of development can be seen from old to new urban layers. New infrastructure like asphalted streets, water and sewage systems, electrical installations, and parking spaces shaped a modern city morphology, with new buildings redefining urban identity.

The rapid economic growth in Nikšić caused a population increase, necessitating significant changes in the city’s structure. A major need was housing, leading to the design and construction of many multi-family residential buildings. These buildings were to be constructed in new urban blocks and equipped with facilities essential for quality living, such as kindergartens, schools, healthcare institutions, retail stores, and cultural facilities.

The full scale of the economic and physical transformation of Nikšić is best seen through the fact that before the war Nikšić was a small town with just over 4,500 inhabitants. In the post-war period, it began developing at a rate surpassed by only a very small number of cities in Yugoslavia. In the period from 1921 to 1941, the population growth was only 20%, while the increase in the period from 1941 to 1961 was 338% or more precisely it increased 17 times. The degree of urbanization of Nikšić correlates with population growth, so in 1953, it was 22.1, in 1961, it was 35.1 and in 1971, it was 49.5.13

Two urban plans placed special emphasis on the placement of public buildings, multi-family housing, and related amenities by forming the second and third urban rings, which physically reflect the population growth and the expansion of new urban areas.

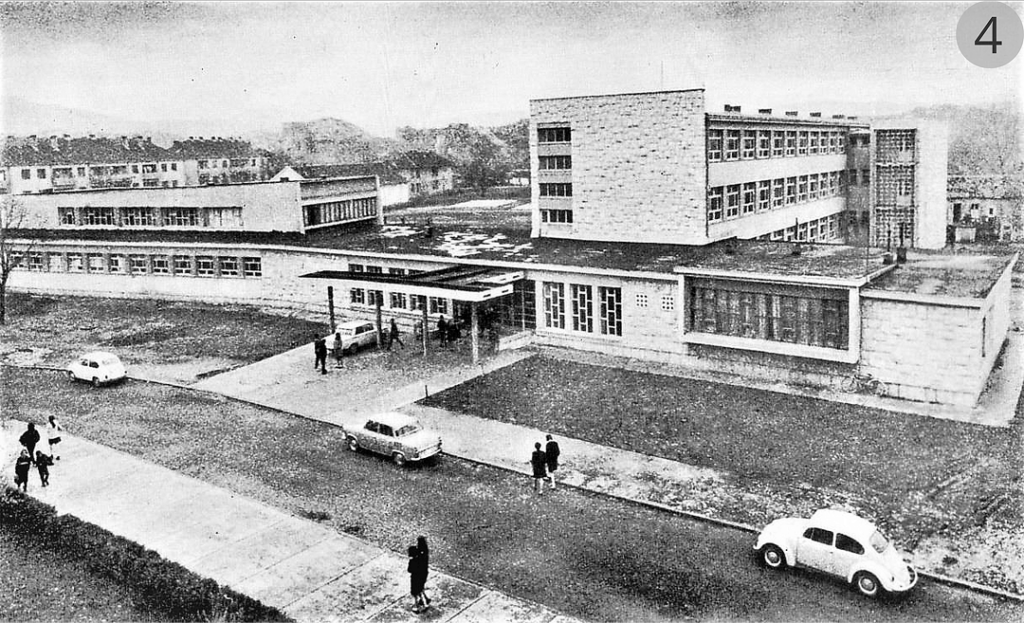

General Plan of Nikšić, 1954–1958: the Basis of the Second and Third Urban Rings

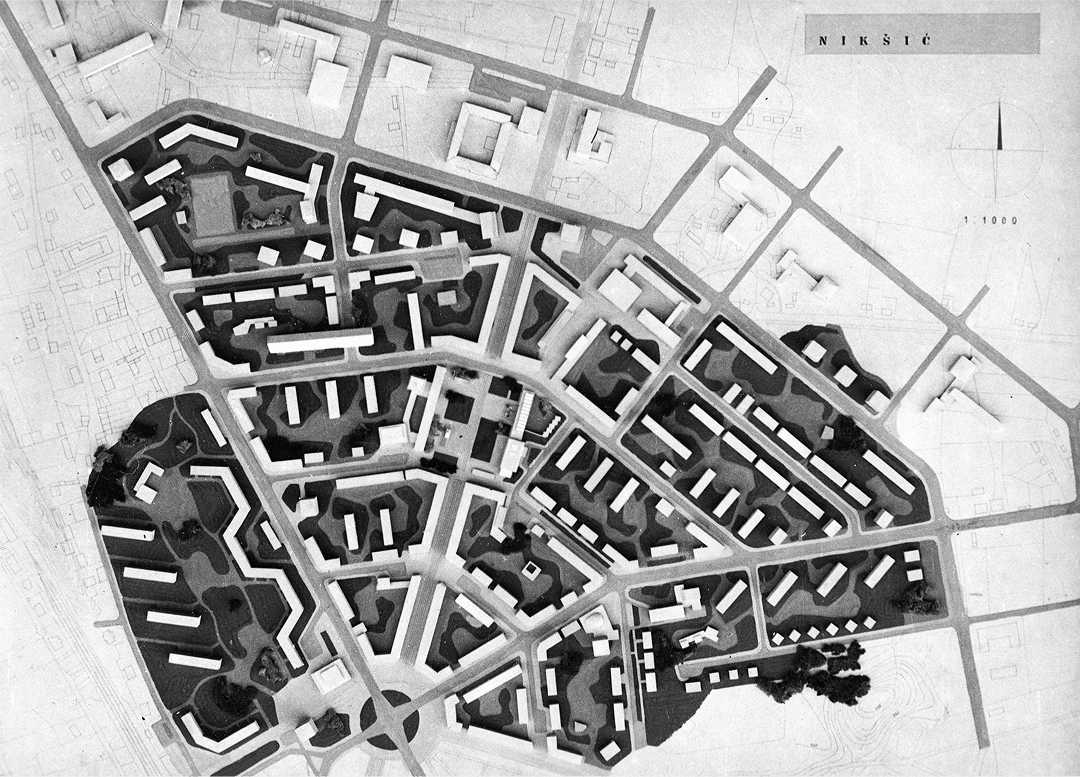

The first post-war general urban plan of Nikšić was created in 1954 by the Institute of Urbanism of the Faculty of Architecture, Civil Engineering, and Geodesy in Zagreb, with the designers being Josip Seissel (1904–1987), assisted by architects Dragan Boltar (1913–1988), Boris Magaš (1930–2013) and Bruno Milić (1917–2009). It is important to note that this urban plan was the first that clearly defined and delineated the broader and narrower construction zones of the city.14

Seissel’s plan bears similarities with Slade’s plan regarding the central green belt, designated for social, public, and representative buildings. It also maintains the central part of the city as per Slade’s plan. Additionally, Seissel’s plan includes a high-rise zone for multi-family housing, featuring block-type buildings with spacious streets and tree-lined avenues, designed to accommodate workers from the industrial zone.

After the mixed-use zone, which includes both collective and individual housing, there are individual, peripheral, satellite, and suburban settlements. The industrial zone is located outside these settlements but closely connected to the city and transit routes. The city’s territorial expansion is planned towards the Bistrica River to the north, northeast, and east, maintaining peripheral development with business and commercial buildings.

A clear indicator of the urban plan’s quality is its full adoption of the principles from Slade’s regulatory plan, ensuring continuity in the city’s development. Additionally, the plan successfully positions its socially significant buildings along a strip next to the historical core. The urban plan’s significance lies in its logical design, which allowed the city to expand concentrically through the formation of urban rings, a structure that future masterplans would continue to reinforce. Although the plan envisioned buildings as being two or one-story, city planners later incorporated a number of three- or four-story buildings, and even five or six-story buildings into the city fabric, which was in complete contradiction to the plan.

General Urban Plan of Nikšić, Urban Planning Institute of Croatia, Zagreb, 1984–1986: the Upgrade of the Second and Third Urban Rings

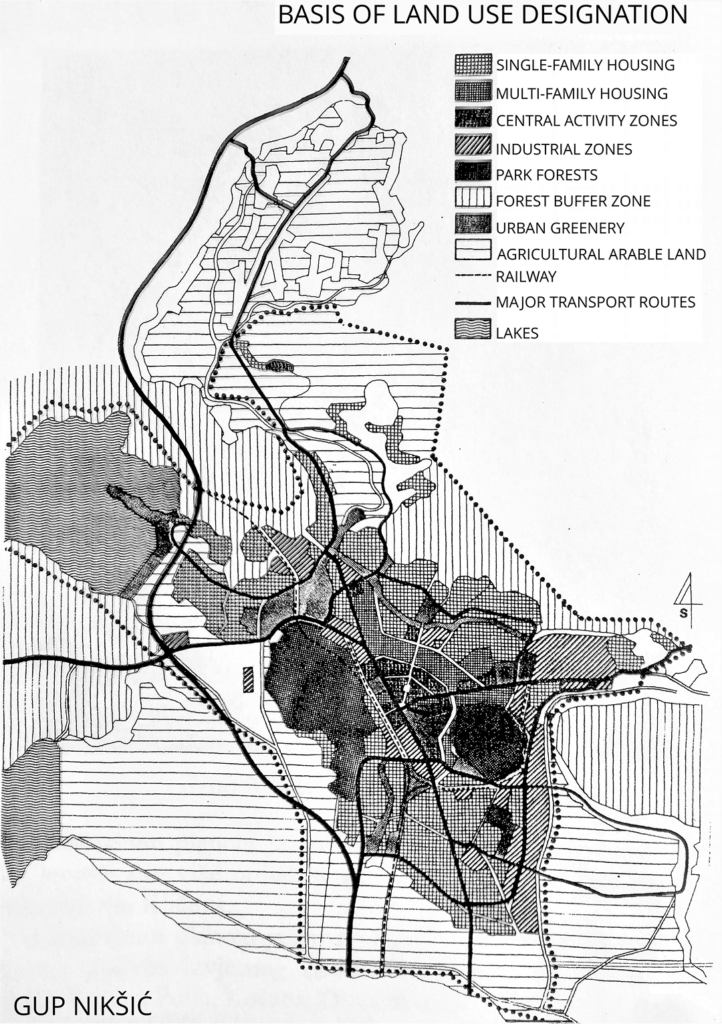

In 1984, the Urban Planning Institute of Croatia in Zagreb prepared the Spatial Plan and General Urban Plan for Nikšić, which was adopted in 1986. The General Urban Plan proposed a division into four areas: the central area, the northern area, the southern area, the western area, and the industrial zone.15

The central area is a fully urbanized zone that aims to preserve authentic, inherited urban patterns. Single-story houses would be replaced with multi-story buildings designed to maintain the existing ambiance, while the extant street and square system would be completely retained. The importance of the General Urban Plan lies in its protection of the city’s historical core and in the protection, expansion, and enhancement of green spaces, especially the city park, Trebjesa Forest, Studenačka Glavica, Uzodmir, the Bistrica and Zeta rivers, and the Krupac and Slano lakes. The plan also emphasizes the preservation of cultural heritage sites. The northern area is planned for the development of green spaces along the Bistrica River and designated for individual residential development. The southern area is set to develop suburban settlements, particularly in the local communities of Kličevo and Straševina, and includes designated industrial areas. The western area, as in the northern area, is also intended for individual residential development. Additionally, a green belt is planned along the Zeta River, alongside the reconstruction and enhancement of existing traffic infrastructure.

The General Urban Plan further solidified the spatial structure and contents of the second and third urban rings, formed previously during the implementation of the 1958 urban plan.

Relationship between Postwar Urban Plans and the First Regulatory Plan

An examination of the post-war urban plans for Nikšić reveals its strong foundation in Slade’s plan. The authors aimed to facilitate the city’s expansion logically, building upon the first regulatory plan as the groundwork. This initial plan not only established the dominant urbanistic form and elements but also introduced specific architectural styles that evolved from it. The post-war plans incorporated solutions that honoured this architecture, infusing it with new vitality.

The 1958 plan allocated ample space for individual construction and provided flexibility for the construction of public buildings of various sizes, designating areas for block-type planning, suitable for both individual and public buildings. Moreover, the General Urban Plan of 1958 established the first urban ring of Nikšić, further differentiating its spatial characteristics. In parallel, this plan facilitated the city’s logical expansion radially from the centre of the existing urban matrix through the formation of new urban rings with clearly defined functions.

The 1984 General Urban Plan of Nikšić reinforced the principles of the 1958 plan, facilitating city expansion through newly defined urban locations. In this context, the second and third urban rings became significant in shaping Nikšić’s recognizable urban identity. The application of post-war plans directly relates to the continuity of the city’s development.

It should be emphasized that the development of urban planning documents was, among other factors, influenced by changes in the city’s population. For instance, the urban plan from 1958 was created when the city had 57,399 inhabitants. By the late 1970s, just before the development of the General Urban Plan in 1984, Nikšić had a population of 71,299. In the early 1990s, the population stood at 74,706, while at the beginning of the 21st century, it slightly increased to 76,677. Currently, due to depopulation, the city has a population of 65,705.16

Architecture of the Second and Third Urban Rings of Nikšić

Following the end of the Second World War, Nikšić experienced a period of intensive construction and rebuilding of its war-damaged areas. Prominent Yugoslav architects, including Rajko M. Tatić, Ivan Štraus, Marko Mušič, Đorđije Minjević, and Slobodan Vukajlović, played a significant role in shaping the city’s architectural landscape. In addition, Montenegro’s first formally trained architects, such as Petar Vukotić and Vujadin Popović, made substantial contributions, with Đorđije Minjević notably completing the landmark Onogošt Hotel.

These cited architects designed significant architectural works within the second and third urban rings, further solidifying the urban composition of these areas. This architecture can be examined chronologically by decade, spanning the period from 1950 to 1990.

Architecture of the Second and Third Urban Rings in the Period 1950–1960

The most significant architectural achievements in the second and third urban rings of Nikšić during the period from 1950 to 1960 were designed by architects Periša Vukotić and Rajko M. Tatić.

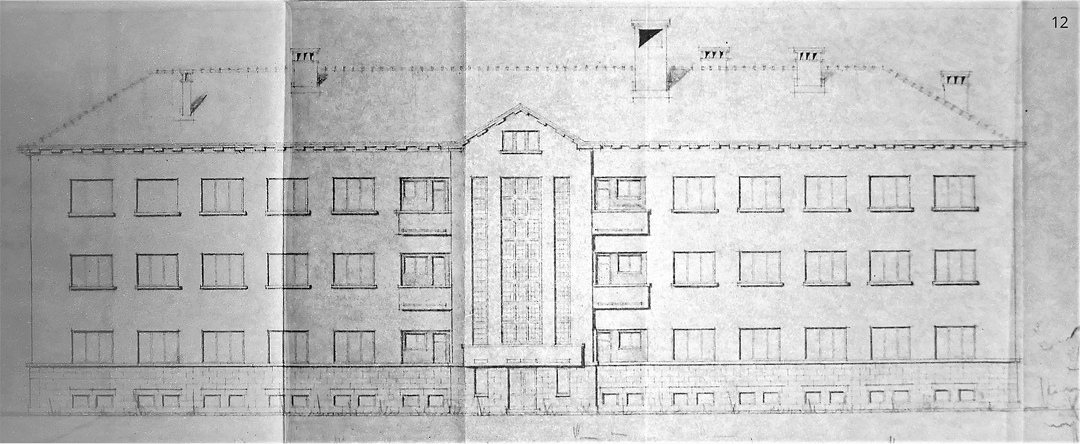

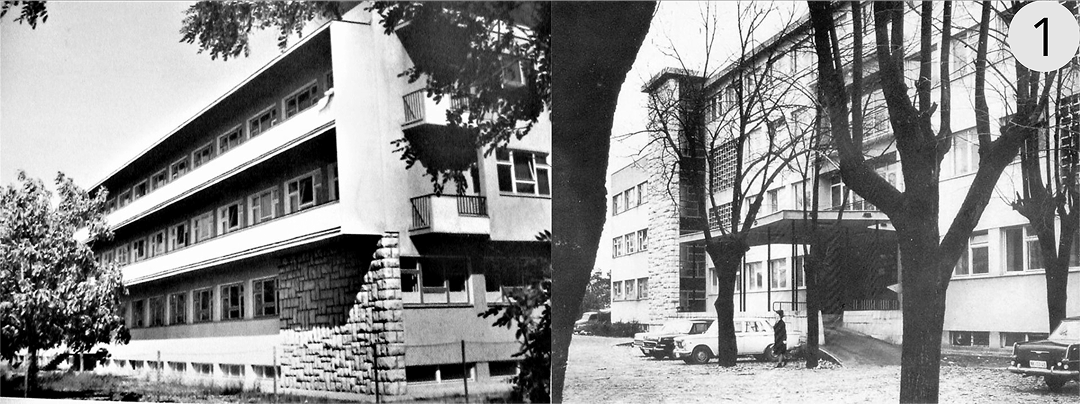

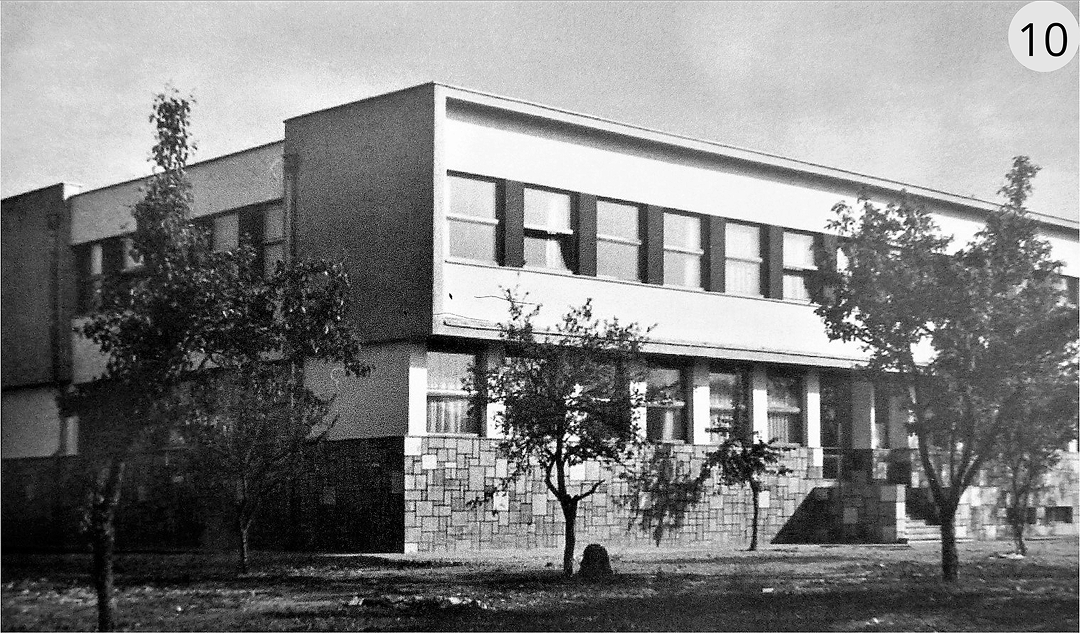

Periša Petar Vukotić (1899–1988), one of the first formally educated architects in Montenegro, designed two significant buildings in the second urban ring of Nikšić: the Elementary School (1947–1948) and the Administrative Building for the Construction Company (1955–1958). These buildings represent the first public post-war structures in the city. A key characteristic of Vukotić’s architectural style is the simplicity and predominantly symmetrical design of his buildings, often constructed atop foundations of dressed stone blocks.

Rajko M. Tatić (1900–1979), a prominent Serbian and Yugoslav architect, is the author of four buildings in Nikšić. Among these are a residential building with offices on the ground floor and the National Bank building, both located on Njegoševa Street in the second urban ring. The residential building was completed in 1955, while the National Bank building was finished in 1956. Both structures are situated at the boundary between the part of the city developed according to the first regulatory plan and the part earmarked for modern construction to meet contemporary needs. Through these two buildings, Tatić succeeded in creating one of the most recognizable parts of Nikšić.

The other two buildings are identical residential structures located in the third urban ring, on Dr. Niko Miljanić Street, completed in 1956. The architecture of these buildings is calm and unpretentious yet still engaging, particularly in the rhythm of the design, with the southern façades being dominated by balconies.

Architecture of the Second and Third Urban Rings in the Period 1960–1970

The most valuable architecture in the second and third rings of Nikšić was created by architect Đorđije Minjević, who applied the principles of the international style in harmony with local conditions.

Đorđije Minjević (1924–2013) is one of the most prominent Montenegrin architects, whose work had a profound impact on the city of Nikšić after the Second World War. During the period from 1953 to 1963, Minjević worked intensively in Nikšić, designing around thirty structures for various purposes, including schools, hotels, recreational and cultural facilities, as well as industrial and administrative buildings.

The fundamental characteristics of the buildings designed by Minjević were shaped by several factors. First, the era in which these buildings were constructed was marked by a strong desire to rebuild the war-torn land and cities, and to do so in accordance with contemporary architectural trends. However, this period, despite the great drive for progress, also faced significant challenges, particularly in terms of both professionally trained personnel and available materials. The interplay of these factors nonetheless acted as a stimulus to the architects’ enthusiasm, allowing them to present the profession of architecture in its most refined and optimal form. Minjević designed a wide range of functionally diverse buildings, actively incorporating advancements in technology, functional processes, and the specific needs of each project. The result was a clear and efficient functional organization. Minjević replaced the lack of modern materials, especially for finishing, with the use of local materials, which in the era of modernism nevertheless achieved an associative connection with traditional construction.17

In his writings, Minjević most clearly articulates the fundamental criteria in design by stating that, in almost all cases, his approach to buildings began with the integration of two key principles of modern architecture: function and design. In terms of the building’s physiognomy, particular attention is given to the following elements: the entrance, corridors with staircases or other means of communication, windows, attics, and the roof. In the second urban ring, Minjević designed several notable buildings, including the Surgical and Gynaecological Hospital (1960), the Olga Golović Elementary School (1955–1957), the City Hall of Nikšić (1962), the City Court (1963), and the Pedagogical Academy (1962). In the third urban ring, he designed the Ratko Žarić Elementary School (1961) and a multi-family residential building, in collaboration with architect Slobodan Vukajlović.

Architecture of the Second and Third Urban Rings in the Period 1970–1980

Among the most prominent Montenegrin architects who designed in the second and third urban rings of Nikšić between 1970 and 1980 are Slobodan Vukajlović and Dušan Duda Popović.

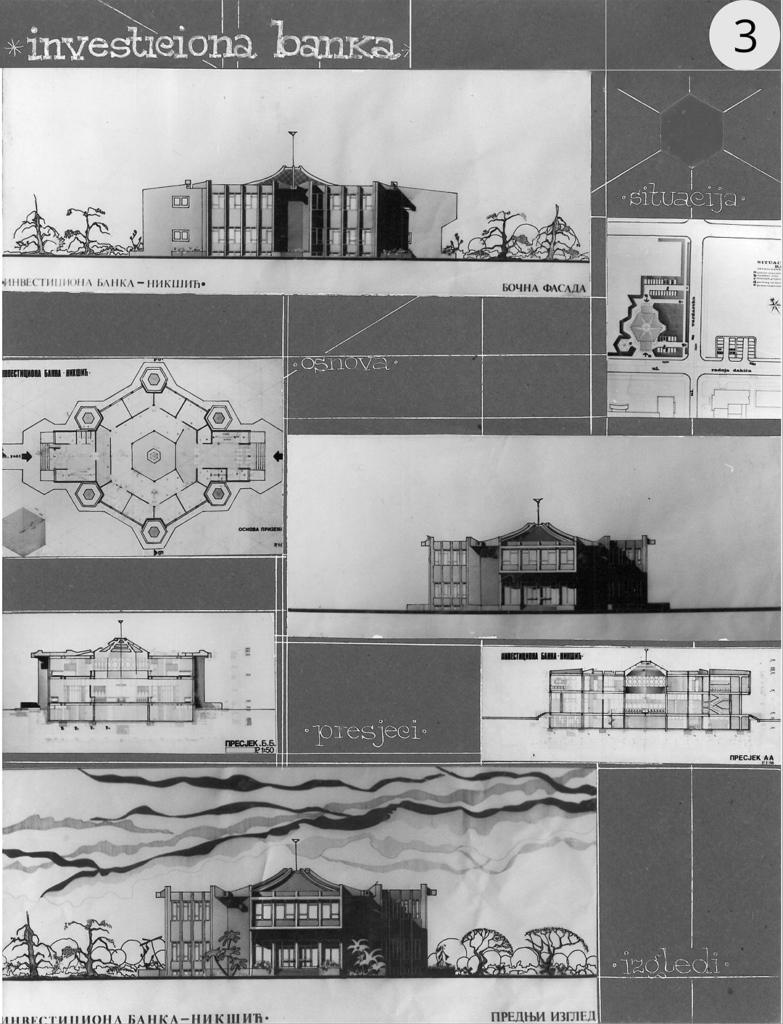

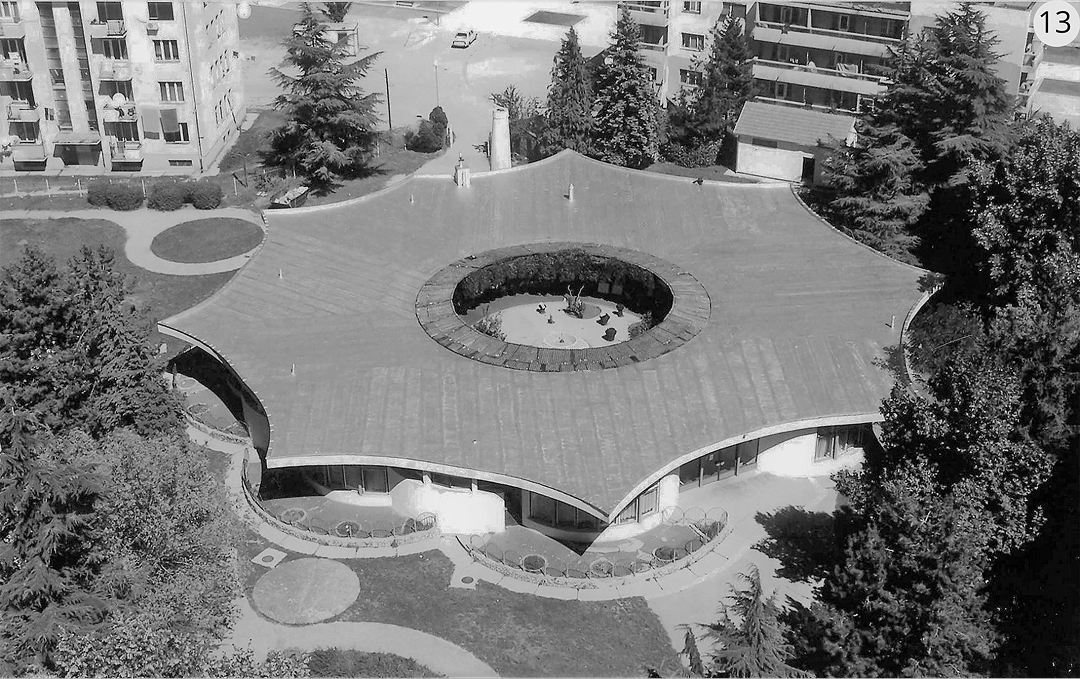

Slobodan Vukajlović (1934–2006) was the first Montenegrin architect to earn a PhD in the fields of architecture and urbanism in Krakow. Through a Polish government fellowship, Vukajlović pursued doctoral studies in architecture from 1974 to 1978, when he defended his thesis titled “Hexagonal Systems in Architecture,” under the mentorship of Professor Tomasz Mankowski (1926–2012).

It is noteworthy that Vukajlović designed the majority of his projects in Nikšić and its surrounding areas. Several of these buildings were designed using typologies previously never applied in the city, thus contributing to the positive transformation of its spatial identity.

Considering the extensive typology of projects designed by Slobodan Vukajlović, it can be categorized, broadly speaking, into urban planning solutions, reconstructions of existing buildings, memorial-monumental architecture, and architectural designs. The stylistic characteristics of Vukajlović’s work are as diverse as they are difficult to define, making it challenging to pinpoint a single pattern or set of stylistic principles that he consistently applied. Although his work has recently been described as “hexagonal architecture” – in which the form of the building is defined by various combinations of volumes based on the hexagon – such interpretations are overly simplistic. Vukajlović’s oeuvre is far more complex, and it is impossible to reduce his approach to just one method or style.18

In the second urban ring, Vukajlović designed the Investment Bank (1974), while in the third urban ring, he was responsible for the design of a kindergarten (1971) and a multi-family residential building, developed in collaboration with architect Đorđe Minjević.

Architect Dušan Duda Popović (1944) is the author of the winning design for the new Health Centre building in Nikšić, which was selected through a design competition in 1972 for the second urban ring. Construction of the building commenced in the same year and was completed in 1976. The Health Center stands as one of the finest examples of Brutalism, not only in Nikšić but in Montenegro as a whole. Popović adhered to the global architectural trends of the time, interpreting them in a distinctive and contextually appropriate manner, resulting in a harmonious and elegant solution. The building’s plasticity, complemented by discrete abstract ornamentation in the form of circular motifs and concrete lines, creates a unique visual experience, further enhanced by the interplay between the individual components and the overall structure, the intensity of texture, and the visual qualities of concrete and glass, as well as the relationship between light and shadow on the façades.

Architecture of the Second and Third Urban Rings in the Period 1980–1990

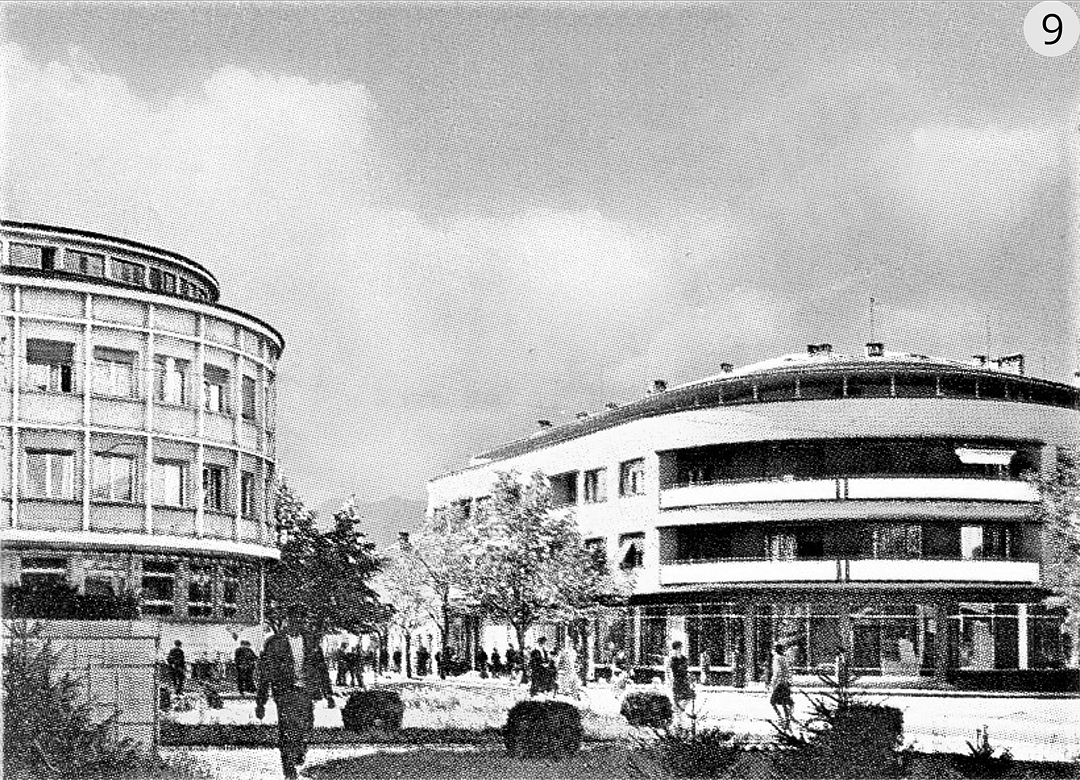

Two of the most prominent Yugoslav architects in the second urban ring of Nikšić during the late 1970s and mid-1980s were responsible for designing two of the city’s most renowned architectural works, among the most significant not only in Montenegro but also in the former Yugoslavia. These architects are Ivan Štraus, with his design of the Onogošt Hotel, and Marko Mušič, with his design of the House of Revolution.

One of the most iconic buildings in Nikšić is the Onogošt Hotel, which serves as both a symbol and a benchmark of the city. It holds significant value as a key part of the urban and collective memory of Nikšić for various reasons.

The current Onogošt Hotel consists of two distinct sections: the original building and the newer addition. The original hotel was designed by Vujadin Popović (1912–1999), a pioneering figure in modern architecture in Montenegro. Significantly, Popović was unable to complete the project due to his emigration to Australia: the task of finishing the design, based on Popović’s initial plans, was undertaken by architect Đorđe Minjević. The old part of the hotel is built in a modernist manner, with clear and legible form. The building has a ground floor with a spacious terrace and three floors with the rooms. The uppermost fourth floor has the hotel’s management, offices and accompanying facilities. The main feature of the old hotel is the stone terrace as one of the favorite places of all Nikšić citizens.

Architect Ivan Štraus (1928–2018) designed the new section of the Onogošt Hotel, following the winning proposal from the 1976 Architecture Contest. The construction of the new part took place between 1977 and 1982. The design of the new hotel is rationally and functionally integrated with the ground floor of the original building, which was a key objective of the project, alongside the introduction of new accommodation units and facilities. The form of the new structure, which evokes various associations and is rich in meaning and architectural expression, represents one of the main values of this building.

In the former Yugoslavia during the 1970s, it was common to construct memorial monuments and buildings dedicated to commemorating the victims of the liberation struggles during World War II, as well as the victories over Fascists and Nazis. One of the most significant memorial structures in Montenegro, the House of Revolution, which remains unfinished to this day, began construction in 1977 in the city of Nikšić. The project was the result of a Yugoslav competition, won by Slovenian architect Marko Mušič (1946) in 1976. Construction ceased in 1989, and in 1992, the building was preserved in its incomplete state. This building serves as a symbolic synthesis of memorial and cultural elements. Memorial aspects are integrated throughout the structure, positioned along corridors and halls, almost as if to remind the visitors, as they moved toward the cultural spaces, that their ability to engage freely with culture was made possible by the sacrifices and lives of the liberators. Furthermore, through its memorial function, the building also honors the victims of other Yugoslav nations, promoting the ideas and values upon which Yugoslavia was founded. In this way, the building functions as a guardian of memory.

The original plan for the House of Revolution envisioned a total area of 7,000 square meters. However, due to requests from the political authorities, the building’s size was expanded to 22,000 square meters. The building was planned to include a variety of facilities, such as a large amphitheatre with 1,200 seats, a summer amphitheatre, a cinema, conference halls, radio and television centres, libraries, educational centres, art studios, galleries, a youth centre, and a national restaurant, among others. Notably, the memorial section of the building occupied only 250 square meters.

With the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991, construction of all federal projects, including the House of Revolution, was halted. Today, the building stands abandoned, left to the ravages of time. It remains unfinished and has never been utilized. Over the years, the building has come to symbolize the antithesis of the ideals it was originally meant to represent.19

Conclusion

Nikšić holds significant importance in the fields of architecture and urbanism for several reasons. Its development was shaped by a unique urban plan based on a radial matrix designed in 1883 by architect Josip Šilović Slade, which remains an exceptional example of urban planning. In the aftermath of the two World Wars, the city underwent profound formal and functional transformations, emerging as a remarkable case of spatial evolution. These changes were driven by the contributions of some of the most prominent Yugoslav and Montenegrin architects, solidifying Nikšić’s place as a notable study in architectural and urban development not only within Montenegro but also across the former Yugoslavia.

A particularly compelling aspect of Nikšić’s urban and architectural character lies in its spatial organization, defined by distinct urban rings. The first regulatory plan established the city centre as the initial urban ring, with its spatial characteristics serving as the basis for subsequent urban plans, particularly those of 1958 and 1984. These post-war plans introduced additional layers to the city’s structure: the second ring, which incorporated significant public buildings, and the third ring, characterized by multi-family residential architecture accompanied by essential amenities.

The interplay between these urban rings has resulted in a unique urban fabric that reflects a distinctive architectural and spatial identity. Nikšić thus represents a vital example of how historical, cultural, and architectural influences can converge to create a singular urban

Environment.

Further research into this unique urban development can provide valuable insights for contemporary urban planning, particularly in the context of preserving cultural heritage and adapting to modern urban needs.

IVANOVIĆ, Zdravko. 1976. Urbanizacija SR Crne Gore. Geografski glasnik, 38(3), p. 177.

IVANOVIĆ, Zdravko. 1979. Razvoj nekih urbanih naselja u SR Crnoj Gori. Geographica Slovenica, 10(1), p. 85.

VOGELNIK, Dolf. 1961. Urbanizacija kao odraz privrednog razvoja SFRJ. Belgrade: Savezni zavod za statistiku.

Spisak gradskih naselja prema popisu stanovništva i stanova. 1973. Belgrade: Savezni zavod za statistiku.

PEJOVIĆ, Đoko. 1969. Naseljavanje Nikšića poslije 1878. Nikšić: Univerzitetska riječ.

Onogošt, 1899, (13), p. 4.

Glas Crnogorca, 1909, (50), p. 13.

ŠAKOTIĆ, Veljko. 1996. Nikšić u njaževini kraljevini) Crnoj Gori. Nikšić: Centar za informativnu djelatnost.

MAKSIMOVIĆ, Maksim. 1961. Prvi regulacioni plan Nikšića. Komuna, 9(17), p. 15.

ŠĆITAROCI OBAD, Mladen and ŠĆITAROCI OBAD BOJANIĆ, Bojana. 1996. Parkovna arhitektura kao element slike grada. Prostor, 4(1), pp. 79–94.

RADOVIĆ, Ranko. 2009. Forma grada, osnove, teorija i praksa. Belgrade: Građevinska knjiga.

Ivanović, Z., 1979, p. 85.

BOJKOVIĆ, Vladimir. 2019. Arhitektura i urbanizam Nikšića nakon Drugog svjetskog rata. Belgrade: Zadužbina Andrejević.

BOJKOVIĆ, Vladimir. 2024. Development of the City of Nikšić through the Planning Documentation of Croatian Architects. Prostor, 32(1), pp. 156–167. doi: 10.31522/p.32.1(67).13

RADOJIČIĆ, Branko. 2010. Opština Nikšić, priroda i društveni razvoj. Nikšić: Faculty of Philosophy, p. 554.

MIĆKOVIĆ, Biljana. 2014. Analiza kretanja broja stanovnika opštine Nikšić u period 1948–2011, korelacija sa procesima industrijalizacije i tranzicije. Tehnika, 69(4), p. 702.

BOJKOVIĆ, Vladimir. 2018. Architecture that brings urban transformation, the case of two buildings in the Montenegrin city of Nikšić. In: CHANCES, Practices, spaces and buildings in cities’ transformation. Bologna, 24 October 2019. Bologna: Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, 419 p.

BOJKOVIĆ, Vladimir. 2018. Hexagonal Architecture of Slobodan Vukajlović: An Example of the City Chapel in Nikšić City, Montenegro. Histories of Postwar Architecture, 1(2), p. 167. doi: 10.6092/issn.2611-0075/7887

BOJKOVIĆ, Vladimir. 2017. Edificio commemorativo La Casa della Rivoluzione, un indicatore della trasformazione dell’identità urbana a Nikšić. IN_BO Ricerche e progetti per il territorio, la città e l’architettura, 8(12), pp. 100–108. doi: 10.6092/issn.2036-1602/7853

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2024.58.3-4.11

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License