The article explores the formative years (1948–1953) of Stavoprojekt, the largest state design institution in state-socialist Czechoslovakia. As part of an ongoing research project, it traces organizational changes using the previously inaccessible archive of the Stavoprojekt Directorate, now held in the National Archives of the Czech Republic. The research is based mainly on the analysis of this fund, which contains fragmentary documents of Stavoprojekt’s operations. The state of the fund itself reflects the early development of the Stavoprojekt organization: inconsistent, ambiguous and haotic. This article aims to clarify the milestones of this development by relating this material to the contemporary literature, periodicals, and legal changes in the fields of architecture and construction.

Much like in other countries of the Eastern Bloc, the post-war political situation in Czechoslovakia gradually evolved towards nationalization and establishment of a centrally planned economy. The construction sector was no exception. The structure of hundreds of private firms and architectural offices proved incompatible with the nature of a planned economy – something Czechoslovak construction experienced firsthand during the two-year economic plan in 1947–1948.**key=1** This very situation created the conditions for realizing long-held visions of industrialized construction, the rationalization of architectural design, and the introduction of scientific methods to architectural practice. This paper brings preliminary findings from the ongoing research “Stavoprojekt 1948–1953. Collectivisation of Architectural Design and its Imprint in the Memory of Czech Landscape and Cities,”**key=2** and follows the organizational changes of the Stavoprojekt state design institution. It is based primarily on materials from Stavoprojekt’s Directorate stored in the National Archives in Prague**key=3** and works with the heuristic method of archival research analysis and interpretation of archival sources. The archive fund consists mainly of fragments of administrative documents, including internal directives, circulars, correspondence, and project evaluation reports. Preservation of the material has been highly disorganized and inconsistent; the most coherent units include internal bulletins and assessments of housing-estate designs. For the purposes of this article, we drew primarily on the administrative documents and correspondence. Their analysis enables a reconstruction of the institutional transformations of the organization during the early years of its existence, which constitutes the main objective of this study.

This paper provides insight into the unprocessed archival collection without claiming to offer a comprehensive overview of its contents. Instead, it uses the available materials to trace the early development of the Stavoprojekt enterprise and open the archival fund to further analysis and interpretation. The timeframe of this overview corresponds to the scope of the collection: it begins in 1948, the year the enterprise was established as part of the Czechoslovak Building Works, and extends to 1954, when the central Stavoprojekt Directorate was dissolved. The paper situates these transformations within the broader context from which Stavoprojekt emerged and subsequently evolved, and it follows the changes in its internal structure along with the accompanying circumstances in a chronological order.

Generally, the topic of architecture and construction in Czechoslovakia during this period has been addressed by numerous monographs and articles in various disciplines, ranging from history,**key=4** art history,**key=5** architectural history,**key=6** to urban studies.**key=7** The topic was also examined from various perspectives, including the socialist city**key=8** the Stalinist transformation of nature,**key=9** building typology,**key=10** scientization in architecture,**key=11** or socialist realism in architecture.**key=12** To date, the institutional background of Stavoprojekt has been addressed in detail primarily by Kimberly Elman Zarecor in her book Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity.**key=13** One of the aims of the present paper is to build upon her work.

Detailed analysis of the institutional beginnings of the enterprise that laid the foundations for state design institutes – institutions significantly shaping the built environment we inhabit today – is itself a significant contribution. In turn, it may also contribute to the broader discussion seeking a more nuanced understanding of the history of the Stalinist period in Czechoslovakia at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s, an era marked by strong contradictions. In this respect, Stavoprojekt can be understood as an institutional framework within which these tensions were manifested in the field of architecture. Understanding its origins and initial transformations can help clarify why the period associated with the historicist-minded idiom of socialist realism in architecture can also be interpreted as a radical modernization project.**key=14**

The Postwar Path towards Collective Design Work

The transformations that occurred after 1948 in architecture and construction were not abrupt; rather, they were the culmination of developments already underway in the immediate postwar period. As early as the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, there was a widespread expectation that “planning would contribute to the comprehensive reconstruction not only of the economy but of society as a whole.”**key=15** After the war, industrialized construction was considered a “rescue” means for mitigating war damage (whether caused by destruction or stagnation), and simultaneously a path to increase efficiency and performance in the construction sector.**key=16** Many avant-garde architects, however, had hoped already in the interwar period that the creation of a new system of organization of architectural design could genuinely resolve many of the problems faced by the construction industry at the time. In 1932, the Congress of Left Architects was held in Prague, resulting in a collection of works entitled Za socialistickou architekturu [Toward a Socialist Architecture], edited by Karel Teige in cooperation with other congress speakers: Adolf Benš, Karel Honzík, Karel Janů, Jaromír Krejcar, Jiří Kroha, Jiří Štursa, Jiří Voženílek. Many of these figures came to play a significant part in shaping the post-war architectural and construction practice,**key=17** which largely represented the fulfillment of their visions.**key=18** Subsequently, in 1933, the Union of Socialist Architects was established with Jiří Kroha as its chairman, and a year later the Block of Progressive Architectural Associations [Blok architektonických pokrokových spolků – BAPS] was established, bringing together several societies.**key=19**

In the post-war period, the work of architects was determined by the idealistic vision of “building a welfare state and, by extension, a better society,”**key=20** and the role of BAPS became crucial. In the summer of 1947, the official BAPS statement On the Cooperation of Architects [O spolupráci architektů] was published. was published. It dealt with the organization of the construction industry, architects’ mission and work, and architecture’s involvement in politics, housing, and planning, as well as other topics addressed already in the pre-war period. Many of these resolutions were published in the revived journal Architektura ČSR, with BAPS taking over its publishing.**key=21**

Following the events of February 1948, a political mandate was now present for the execution of the project of industrialization on an unprecedented scale, with modernization goals no less ambitious than to “fundamentally transform the work and administrative methods.”**key=22** Until then, architectural design was carried out in the offices of private construction companies (94%) or freelance architects (6%).**key=23** This figure was soon to change shortly after the 1948 elections, when Act no. 121/1948 initiated the second and comprehensive round of nationalization, concerning not only companies with more than 50 employees, but also smaller ones.**key=24** The act also established a special department within the Ministry of Technology to prepare for the nationalization of the construction industry.**key=25** Already in February, a national conference of Communist construction workers was convened, which on 29 February 1948 approved the nationalization of construction enterprises. Subsequently, based on a decree from the Ministry of Technology, the Czechoslovak Building Works were established, with the purpose of encompassing virtually all nationalized construction activity in the country. **key=26**

In March, the Action Committee of Czechoslovak Architects [Akční výbor architektů ČSR] was established. established. In its declaration, the committee demanded the dissolution of all architectural associations and institutions, and the creation of a “single cultural, professional, and ideological base for further common activity.”**key=27** Following discussions, several proposals for a solution were drafted based on their objectives. After the Congress of National Culture [Sjezd národní kultury] in April 1948, the architects present supported the proposal for organization of architectural work in geographically dislocated “national ateliers.”**key=28**

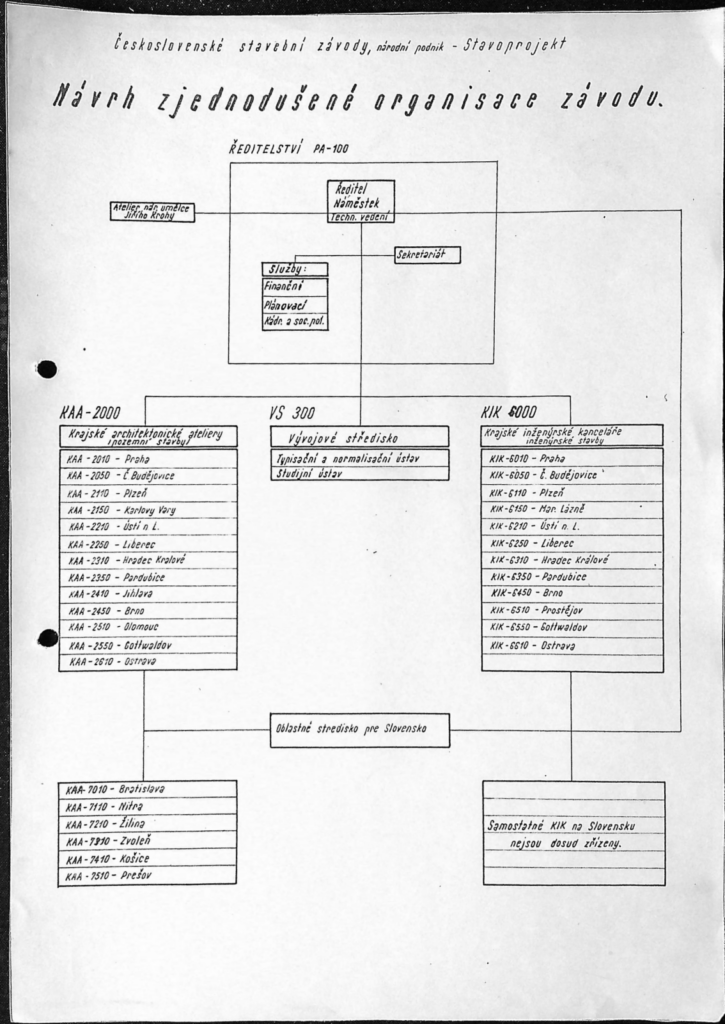

The state design enterprise implementing these demands along with the endeavor for collective work, was established as part of the Czechoslovak Building Works [Československé stavební závody] in September 1948 and called “PA 100 – Stavoprojekt”.**key=29** One of Stavoprojekt’s aims was to separate architectural design from construction work.**key=30** As a subordinate to the directorate of the Czechoslovak Building Works, this objective was partially fulfilled, since the design work was supposed to be handled by Stavoprojekt offices, while construction was carried out by the Building Works’ other subsidiaries. Among practicing architects, however, this solution was not automatically perceived as the only possible or exclusively positive alternative. This lack of consensus is documented not only in the papers from the first national conference of architect delegates of the Union of Czechoslovak Artists [Ústřední svaz československých výtvarných umělců], held later in 1953,**key=31** but also in the words of Stavoprojekt founder Otakar Nový, spoken when recalling the early days of the institution.**key=32** According to Nový, architects were primarily concerned about the excessive subordination of the broader social mission of architecture to the goals of industrial production.**key=33** As subsequent developments have shown, their fears were not unfounded.**key=34** However, other proposed forms of architectural work, such as cooperatives, failed to materialize in 1948.**key=35** Stavoprojekt – along with the design institutes controlled by industry-oriented ministries**key=36** – therefore became the largest enterprise employing most of the professionals involved in architectural design.

Stavoprojekt as Instrument and Object of Central Planning

Stavoprojekt was firmly embedded in the mechanism of the central planning system. The basic concept of economic planning in Czechoslovakia was partly adopted from the procedures of Gosplan, the Soviet state planning authority, as early as 1946.**key=37** However, it was not until 1948 that the construction industry and other sectors in Czechoslovakia began to be governed by centrally issued production plans. From 1945 onwards, an important role in the centrally managed system was played by the Economic Council [Hospodářská rada], an auxiliary body of the government which other planning institutions were part of, including the State Planning Office [Státní úřad plánovací].**key=38** The main advisory body and link between Stavoprojekt and the Economic Council was the Stavoprojekt Architecture Council [Architektonická rada Stavoprojektu].**key=39** In this respect, it may have been inspired by the Soviet model of the Committee for Architectural Affairs [Výbor pro architektonické záležitosti] under the Council of Ministers of the USSR.**key=40** The tasks of the Stavoprojekt Council included overseeing the quality of architectural design and “ideological education.”**key=41** However, according to criticism raised at the 1953 conference of architect delegates of the Union of Czechoslovak Artists, the council’s members**key=42** did not fully exercise their powers, and the council ceased to meet altogether in 1951.**key=43** Thus, this early model of Stavoprojekt’s direct connection to supra-ministerial bodies was unsuccessful.

A different issue was the internal organization of the design company itself. Jiří Voženílek was appointed head of Stavoprojekt in 1948, with Otakar Nový as the first deputy. The choice of Voženílek as director was closely related to the formation of the organizational structure of the newly established enterprise. According to Kimberly Elman Zarecor’s research, Voženílek’s vision and the creation of Stavoprojekt’s institutional model were influenced by his years of previous work experience in the construction department of the Baťa shoe corporation in Zlín, nationalized in 1945.**key=44** Although Voženílek studied Soviet architectural and urban theory since the 1930s and applied it in his work,**key=45** neither Zarecor’s previous research**key=46** nor archival evidence suggests that he was directly inspired by the Soviet institutional basis when creating the organizational structure of Stavoprojekt. Rather, he drew on the local tradition, i.e., the Baťa system.

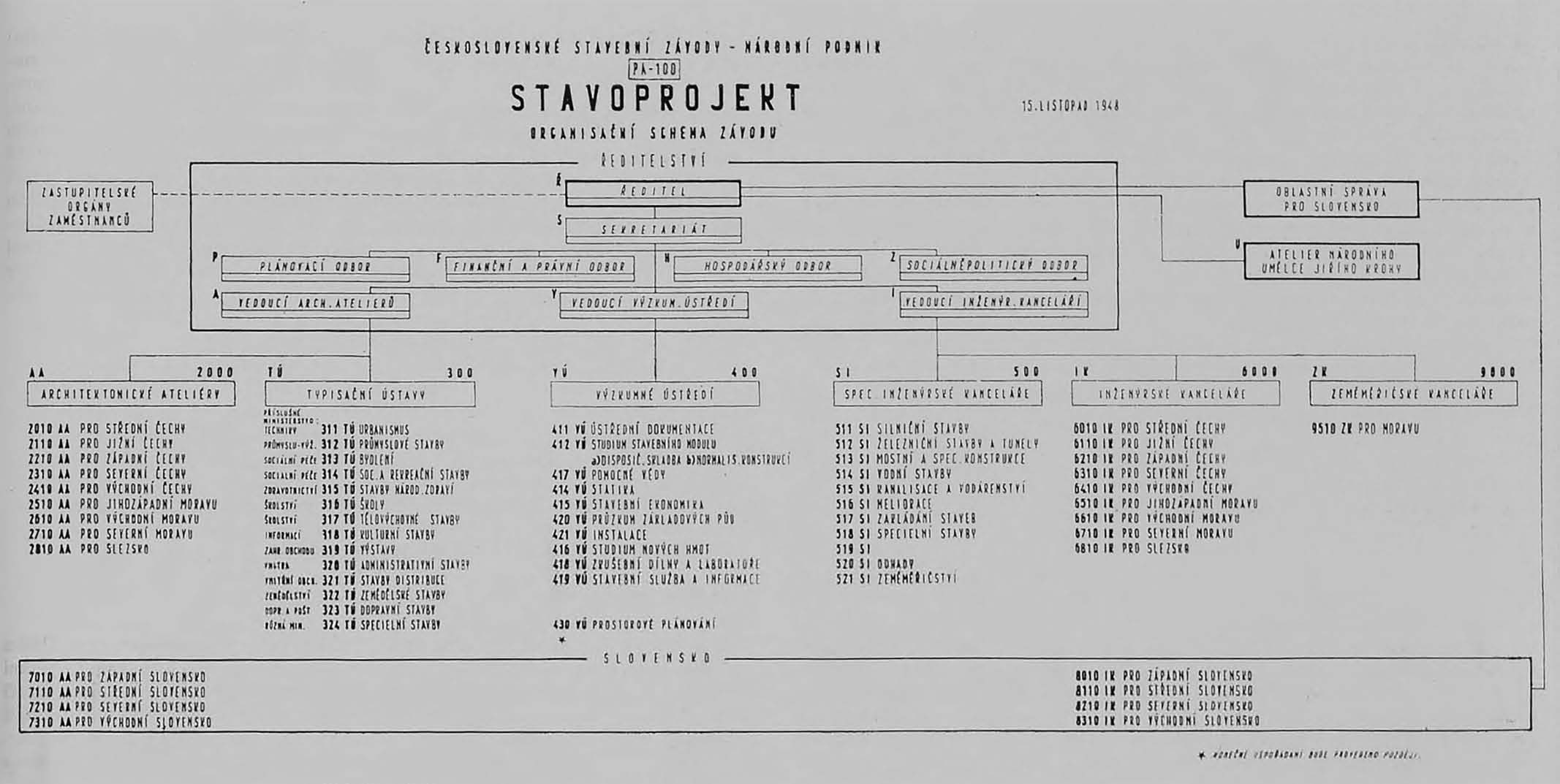

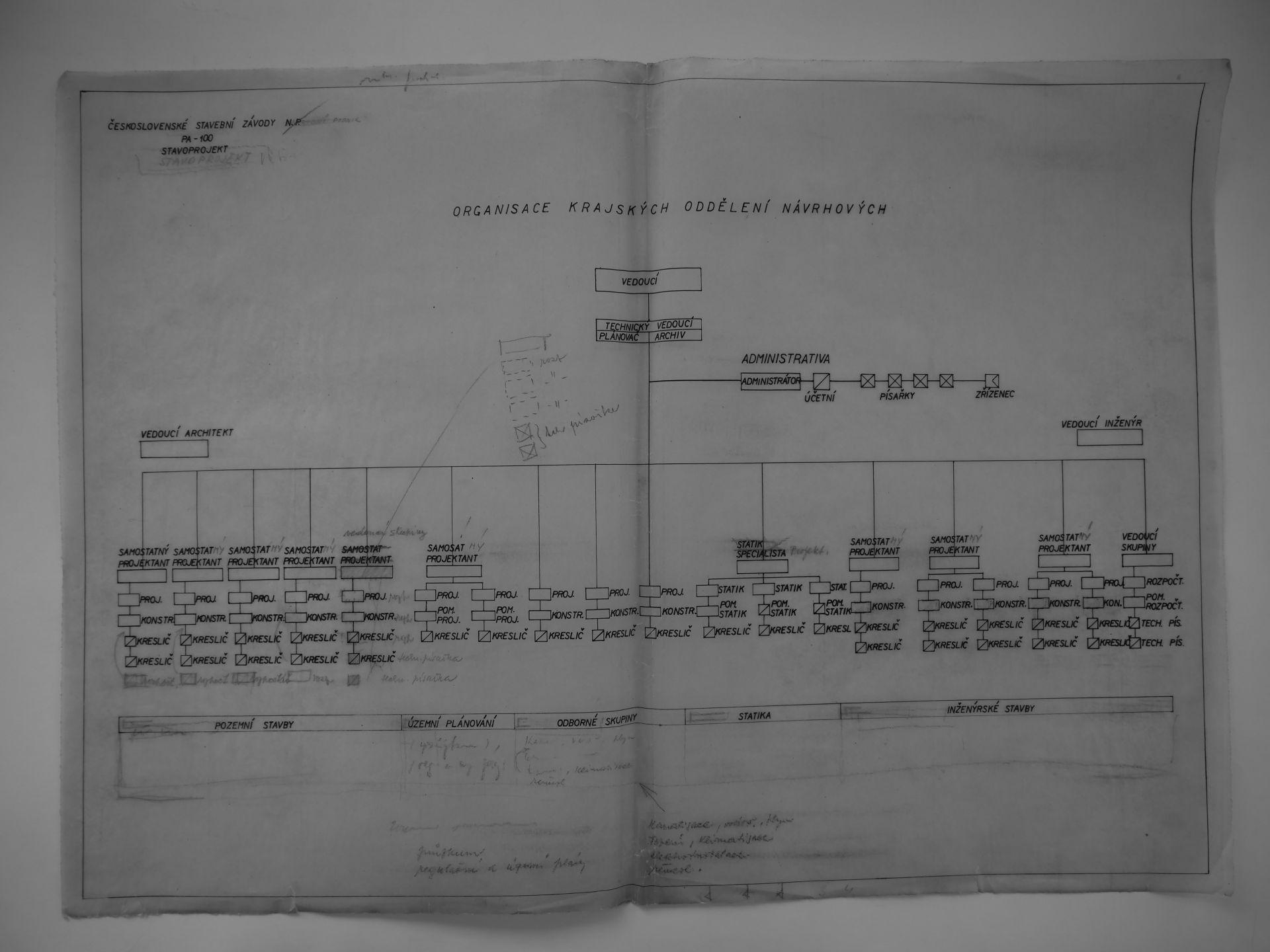

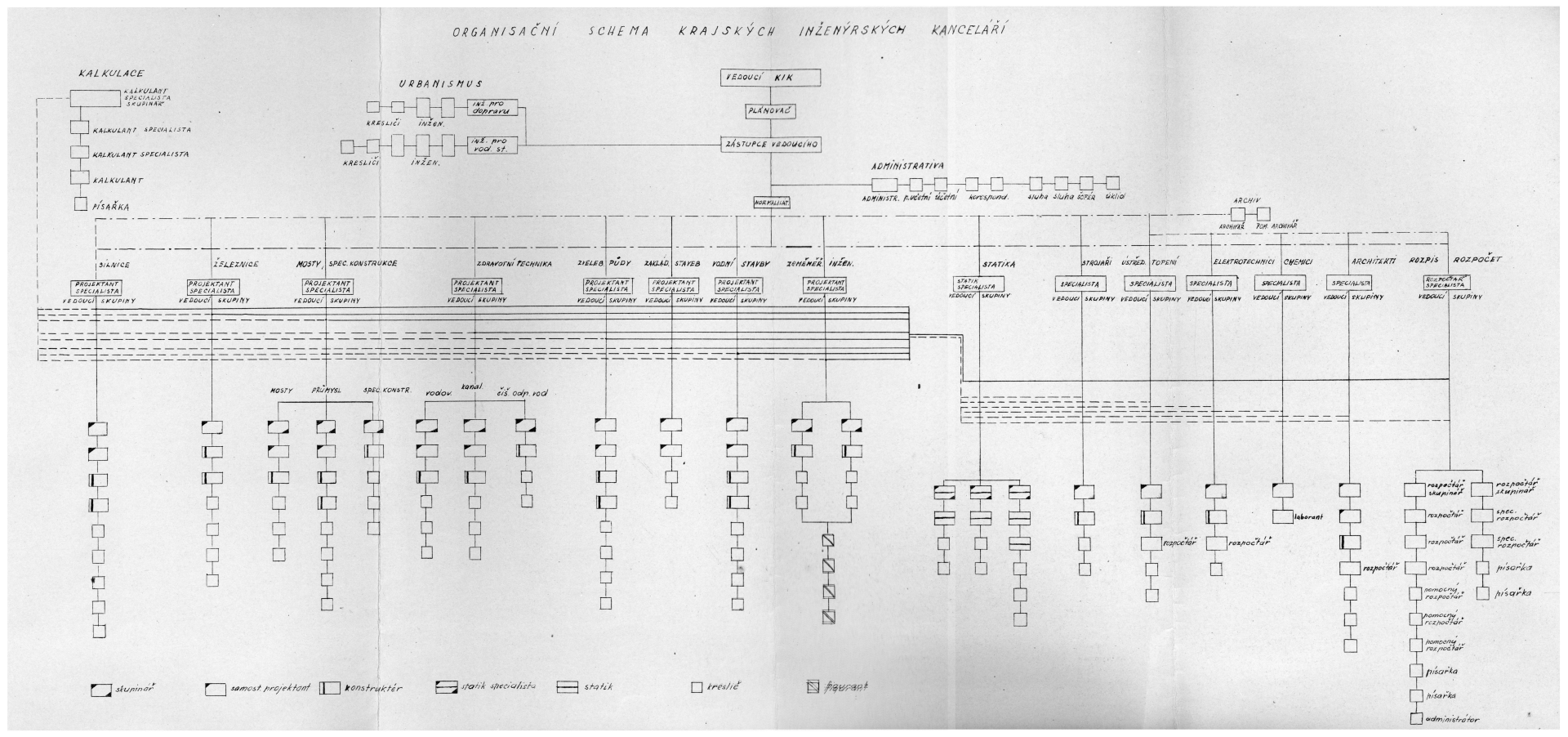

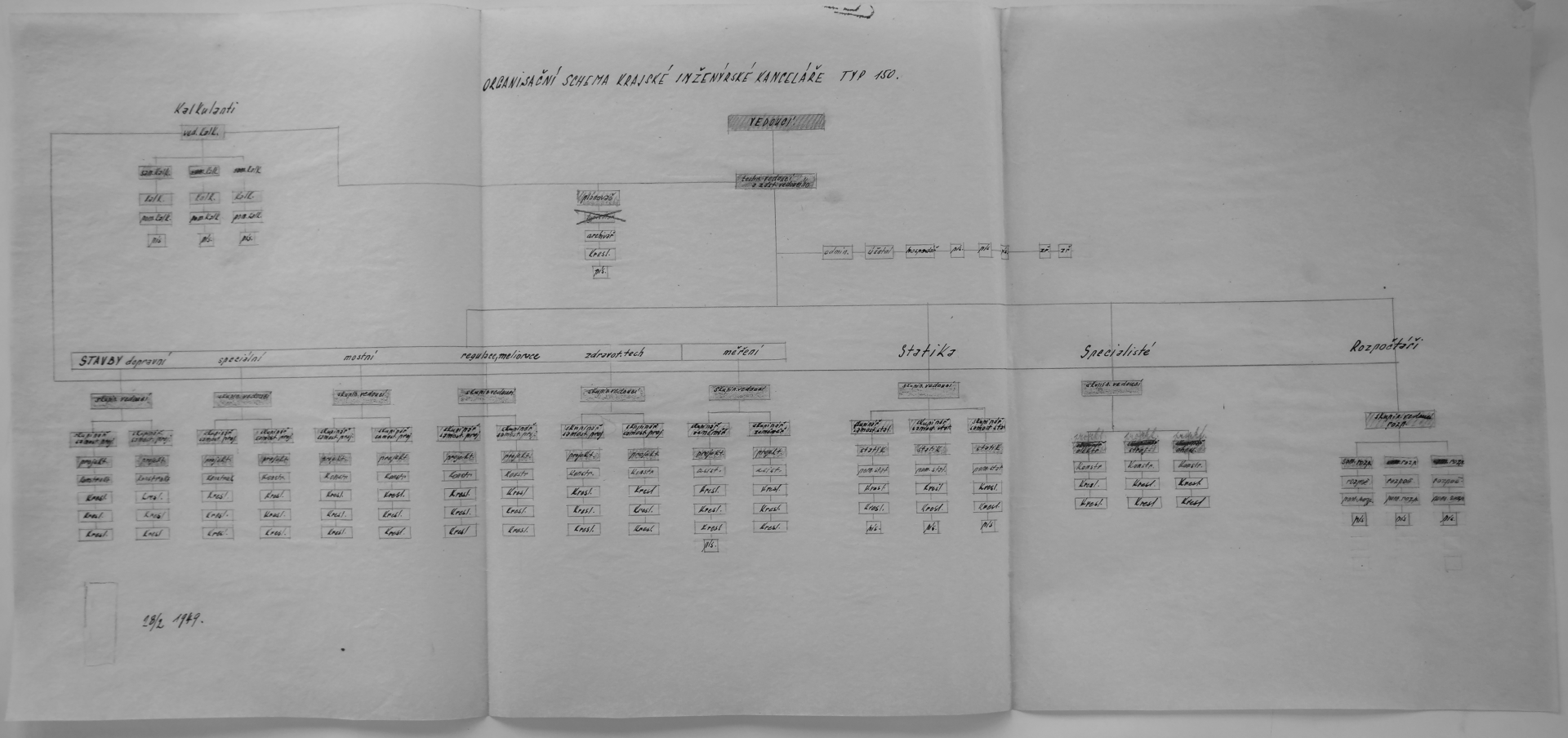

According to the first directive for the establishment of Stavoprojekt, the enterprise was divided into a civil engineering section, known as the “architectural ateliers”, and an engineering department, known as the “engineering offices”.**key=47** This division indicated an initial effort to grant autonomy to both architects and engineers. At the same time, the ateliers and offices were supposed to be equal in status, since, according to Otakar Nový, “the work of an engineer is as creative and cultural as that of an architect.”**key=48**

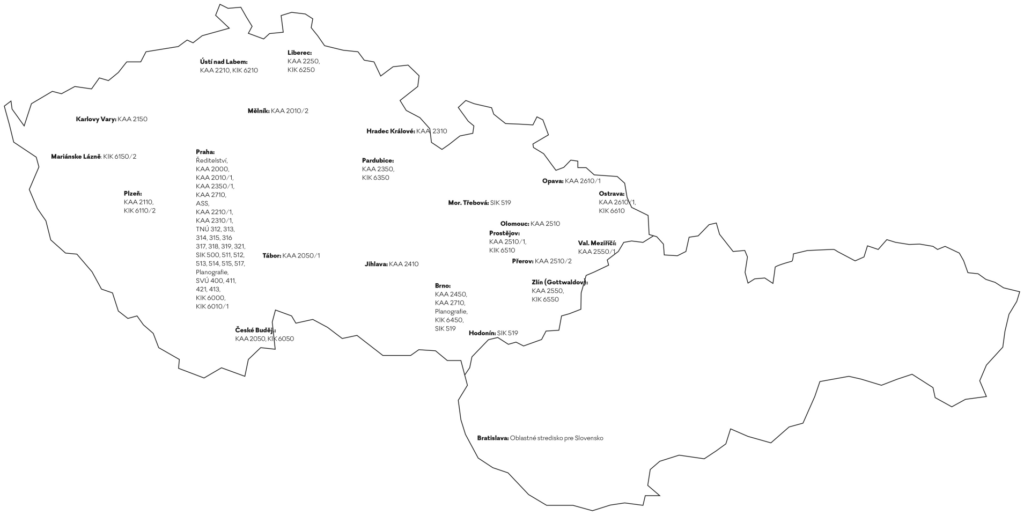

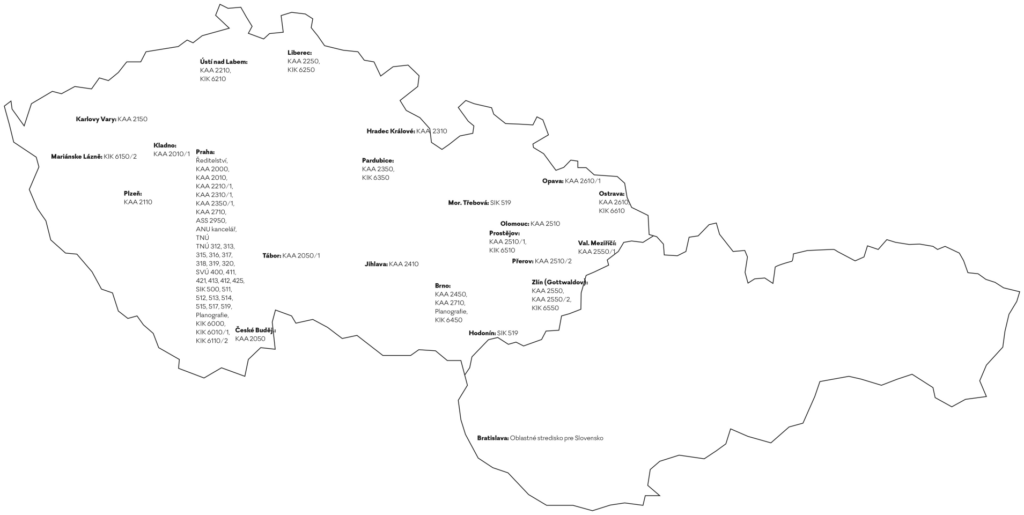

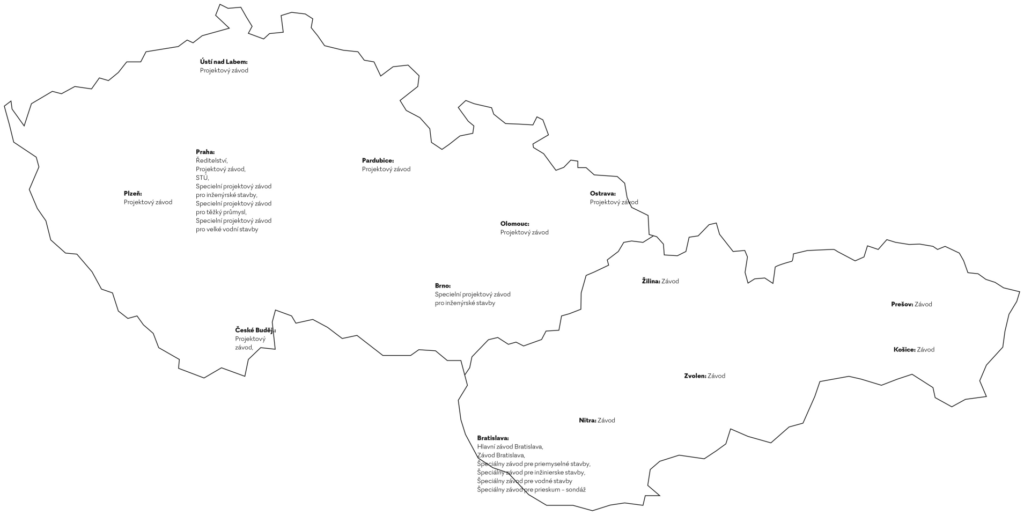

The long-standing ambition to integrate research into architectural design and construction**key=49** materialized in the establishment of the “research section”, common to both the departments of both civil engineering and engineering. In turn, the architectural ateliers were themselves divided into “standardization institutes” and “regional architectural studios”, name that indicates their responsibility for carrying out design work in their respective regions. The structure thus mirrored the new administrative division of Czechoslovakia, introduced at the end of 1948.**key=50** The intention was that projects would be allocated solely on the basis of the location of each studio, but this was never realized.**key=51** Standardization institutes (later merged into a single “Typification and Normalization Institute” were tasked with the “determination of operational and ground plan schemes, standardization of spatial and construction schemes, and standardization of furnishings”, with the plan to publish the produced types and standards as nationally binding or guiding documents for design in regional studios.**key=52** Engineering offices were also further divided into “special engineering offices and regional engineering offices”. The regional architectural studios and regional engineering offices were supposed to be equipped to enable them to independently develop projects ranging from budgets, detailed designs, to production plans. Stavoprojekt in Slovakia was a separate unit directly reporting to the central Stavoprojekt Directorate: the Territorial Stavoprojekt Administration, based in Bratislava and headed by Martin Kusý.**key=53** Regional studios and engineering offices in Slovakia were formed gradually, albeit with a delay due to problems securing enough qualified staff.**key=54**

In accordance with the five-year plan, Stavoprojekt worked on tasks assigned by the national design-work production plan, which it prepared based on directives issued by the State Planning Office every six months.**key=55** From 1948 to 1951, the entire Stavoprojekt was subordinate to the Czechoslovak Building Works, which placed the same legal requirements on it as on any industrial manufacturing enterprise.**key=56** The first directive also prescribed collaboration with the planning department of the relevant construction company, particularly when preparing the site plan, the detailed designs, or the plan for the usage of construction materials.**key=57** The heads of the design studios were required to apply “progressive methods of work, standardization and normalization”, and if these were adhered to, then also to “respect the individual character of the work of independent designers.”**key=58**

In November 1948, Jiří Voženílek published an article in the journal Architekt on the organization of architectural design in the enterprise, also including the first publication of the Stavoprojekt organizational chart.**key=59** This diagram conformed in principle to the structure defined in the first internal directive, with one exception, namely the Atelier of National Artist Jiří Kroha [Ateliér národního umělce Jiřího Krohu – ANU]. Jiří Kroha’s atelier was subordinate only to the Directorate, and his privileged position as the sole “national artist” among architects along with his longstanding Communist views allowed him access to exclusive designs after 1948.**key=60** The atelier was involved in projects such as the redesign of the Strahov Stadium, the design of the new socialist city Nová Dubnica, and other politically significant projects.**key=61**

From the outset, it was clear that the issue of providing suitable offices for the growing number of Stavoprojekt employees would need to be addressed. According to correspondence from September 1948, finding suitable premises in the regions was not an issue; however, Prague lacked the capacity to accommodate departments of between 50 to 120 people working together.**key=62** Meanwhile, Stavoprojekt staff were under great pressure as they had to prepare plans and designs for the first year of the first five-year plan, worth 24 billion crowns.**key=63** Moreover, definitive plans for 1949 in the construction sector were not finalized until November 1948. Therefore, plans for work due to commence in spring 1949 had to be prepared within an exceptionally short timeframe of four months. Stavoprojekt prepared these plans in decentralized studios in the regions, but the design of standardized buildings and elements needed to be concentrated in Prague, for purposes of inspection by the relevant ministries.

Consequently, the greatest demand for premises suitable for design work was in the capital. The Czechoslovak Building Works did not want to solve this problem by commissioning new buildings for the designers, as construction funds were intended primarily for workers’ accommodation.**key=64** In 1948, Stavoprojekt representatives considered Prague’s cafés (such as the Louvre, Valdek and Svět) as the “only option” for immediately locating design offices, drawing rooms and the research and standardization service in Prague. It is unclear whether this option was ultimately pursued and if architects and engineers ever worked in these spaces.**key=65** However, many studios, not only in Prague but also in regional capitals, found premises in residential buildings or the offices of former freelance architects.**key=66** Apparently, the fragmentation of studios and offices into multiple locations, even within a single city, made it difficult to follow prescribed design procedures.**key=67**

The First Year in Operation:

Between Transformation and Stabilization

By the beginning of 1949, Stavoprojekt employed a total of 1820 people in its Czech offices and 161 in its Slovak ones. According to the Situational Report [Situační zpráva o Stavoprojektu] of 18 March 1949, 18.5% of these employees had been transferred to Stavoprojekt from nationalized construction firms, 13% from other national enterprises (besides the Czechoslovak Building Works), and 18% were former civil servants. A further 42.5% were freelance designers (and their employees) whose practices had been nationalized. The remaining 8% were university students and graduates.**key=68** The majority of employees worked in regional architectural studios (1094) and regional engineering offices (436) in Prague and other Czech regions.**key=69**

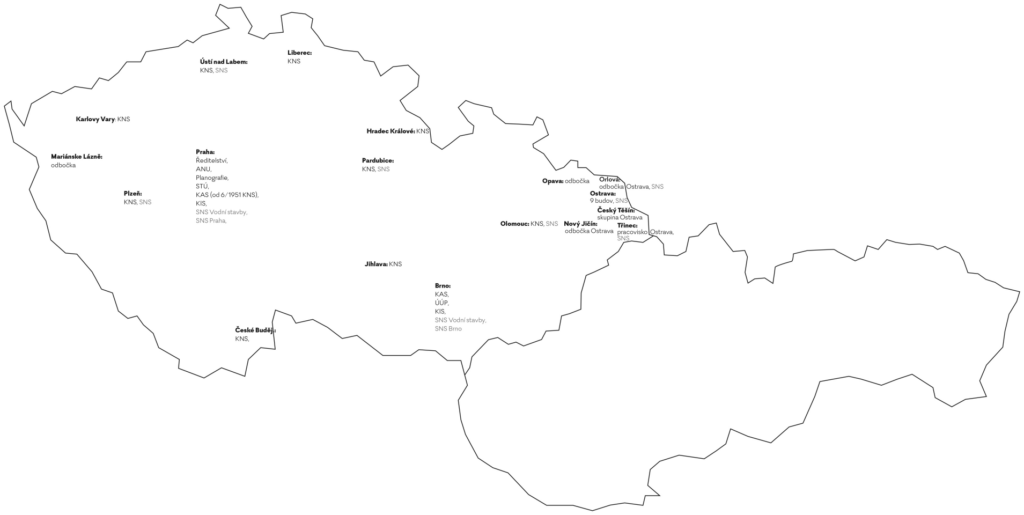

At the beginning of 1949, Stavoprojekt issued a new organizational directive which already reflected the experience of the first months of operation.**key=70** Minor organizational changes to the structure of Stavoprojekt occurred as early as May 1949.**key=71** In regional capitals besides Prague and Brno, architectural studios and engineering offices were merged into “regional design centers”. This change was probably an attempt to reduce the administrative apparatus,**key=72** but it also reflects the efforts to integrate the work of architects and engineers more closely.**key=73** The Typification and Normalization Institute was renamed the Study and Typification Institute [Studijní a typisační ústav]. Stavoprojekt established an Institute of Spatial Planning [Ústav územního plánování] in Brno,**key=74** and two “special design centers” in Prague and Brno, most likely taking on the role of designing large engineering and industrial structures.**key=75** Furthermore, plans for the location of studios in Slovakia, which were only taking shape at the beginning of 1949, were revised. Instead of the intended four locations (western Slovakia, central Slovakia, northern Slovakia and eastern Slovakia), they were placed in six regional cities: Bratislava, Nitra, Žilina, Zvolen, Košice and Prešov.**key=76**

The number of employees at Stavoprojekt increased steadily as a result of the gradual expropriation and closure of private practices, rising in July 1949 to 2436 people.**key=77** In 1950, the Directorate issued a new organizational code.**key=78** The introductory passage states that, unlike the design departments of enterprises or ministries, Stavoprojekt ensures “by its organization and facilities the design tasks in their entirety and across the entire state”, while emphasizing regional decentralization. The structure below, as depicted in the 1950 organizational code, shows also the importance of auxiliary departments that support the design offices, such as print and model shops, as well as departments collecting source materials, literature, and documentation.

- Stavoprojekt Directorate

- Territorial Stavoprojekt Administration Bratislava

- Specialized units:

- Study and Typification Institute Prague

- Institute of Spatial Planning Brno

- Special Design Centers

- Ateliers of National Artists

- Regional units:

- regional design centers

- regional architectural studios in Prague and Brno

- regional engineering offices in Prague and Brno

- Auxiliary units:

- Planography, library, model shop, photo reproduction, kitchen.

Since 1950, the enterprise had to respond to several legislative changes. Following the ratification of Act no. 103/1950, national industrial enterprises became “an exclusive legal and industrial form of production completely subject to state plans” and to the respective ministry.**key=79** This act was subsequently extended to cover enterprises in the construction industry as well.**key=80** At the end of 1950, the government Decree no. 159/1950 abolished the Ministry of Technology and established the Ministry of Construction Industry in its place.**key=81** The activities of the Czechoslovak Building Works, and therefore Stavoprojekt, were transferred to the new ministry. In response to these developments,**key=82** several new “special design centers” dealing specifically with heavy industry were established by Stavoprojekt in Prague, Brno and Ostrava in June 1951, along with divisions in Plzeň, Ústí nad Labem, Pardubice, Olomouc, Třinec and Orlová.**key=83** These offices and their detached working groups were located in industrial centers and focused on designing for the mining, metallurgical, energy, chemical, and heavy and light industry sectors.**key=84** Furthermore, a special design center dealing with engineering was established, comprising departments, branches, and working groups focusing on designs such as roads, railways, cableways, bridges, airports, sewerage systems and treatment plants, water networks, or drainage systems.

No institutional changes in Stavoprojekt relating to the legislative status of national enterprises in the construction industry reached culmination until October 1951. This time, however, it was not just a new internal directive, but a new status for the enterprise as such. On 29 October 1951, Stavoprojekt became an independent national enterprise, now being separated from the assets of the Czechoslovak Building Works.**key=85** Simultaneously, the Czechoslovak Building Works were dissolved, and their liquidation continued for several more years.**key=86** From that moment on, Stavoprojekt was subordinated directly to the Ministry of Construction Industry.**key=87** This also marked the end of Voženílek’s tenure as director of Stavoprojekt. Bohumil Vondráček was appointed in his place,**key=88** after which Voženílek moved to manage Stavoprojekt’s Institute of Architecture and Spatial Planning [Ústavu architektury a územního plánování] in Brno. Two years later, this became the independent Research Institute of Construction and Architecture [Výzkumný ústav výstavby a architektury – VÚVA].**key=89**

Reorganization as a Reflection of Power Transitions

Further organizational changes within Stavoprojekt can be linked to the broader shifts in cultural policy in Czechoslovakia following the arrest of Rudolf Slánský, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, at the end of 1951.**key=90** The arrest and subsequent conviction of the “Slánský Group” for an alleged anti-Party conspiracy in a show trial in 1952 was used, among other ends, to criticize the policies of the Culture and Propaganda Department of the Communist Party Central Committee, and the previous direction of the cultural sphere in general.**key=91** The term “slánština”, or “Slánský-ism”, an ideological label derived from Slánský’s name and generally associated with “bureaucratic management at all levels of decision-making,”**key=92** was then used to denounce previous methods at the second conference of the Union of Czechoslovak Artists in June 1952,**key=93** attended also by representatives of the Union of Architects.**key=94**

Thus, the transformation of cultural political discourse was also reflected in developments in architecture,**key=95** including Stavoprojekt’s structure and internal documents. The change in interpretation of the enterprise’s origins by its own representatives is reflected in the Provisional Statute of National Construction Enterprises [Prozatímní statut národních podniků stavebních] documentfrom late 1952. According to the document, in 1948, “it was necessary to organize more than 1100 nationalized private construction firms under a unified management in a short period …” Consequently, “the organization was carried out as quickly and uniformly as possible without disturbing the design and building projects by administrative work. Therefore, a single national enterprise – the Czechoslovak Building Works – was established, covering the entire sector and country.”**key=96** This stage was intended to lead to the formation of “a greater number of smaller organizational units” and “lay the foundations for the transition from handcraft to industrial production.”**key=97** The document describes these methods as outdated and inadequate for the task at hand, criticizing the hierarchical organizational structure of management. The document denounced “the inflexibility of management, leading to the application of bureaucratic office methods and irresponsibility”,**key=98** which echoes contemporary criticism of “slánský-ism”.

Efforts were made to resolve these perceived shortcomings through change at the supra-ministerial level. On 8 July 1952, Government Resolution no. 28/1952 was issued, which established the Government Committee for Construction as the supreme body responsible for managing all construction in Czechoslovakia.**key=99** Among other things, the Committee took over the assessment of investment tasks, initial designs and investment budgets, as well as the registration of approved investment items, initial design of supra-limit investments and approved standard designs.**key=100**

The last major formal transformation of Stavoprojekt during its existence as a single organization was also related to these national-level changes. On 1 January 1953, the Stavoprojekt national enterprise changed its legal status by decision of the Minister of the Construction Industry to the “State Institute for Housing Estate Design and Civil Engineering – Stavoprojekt.”**key=101** The national enterprise thus formally became a state institute whose name now reflected the focus on residential buildings; the design of other building typologies was later gradually taken over by the respective ministries.**key=102** Bohumil Vondráček remained director of the institute, and Jiří Vohrna was appointed director of the Branch Institute for the Management of Slovak Centres [Pobočný ústav pro řízení slovenských středisek].**key=103** This branch was the superior body of all the Institute’s design centers in Slovakia.**key=104** On 1 July 1953, Stavoprojekt state institute was transferred from the Ministry of Construction Industry to the Ministry of the Interior.**key=105** According to the then Minister of the Interior, Václav Nosek,**key=106** the aim was “… to bring the matters of construction in the regions, from planning documents to individual projects, together in one place.”**key=107**

In 1953, the first nationwide conference of Czech and Slovak architects from the Union of Czechoslovak Artists took place. The conference materials confirm the critical tone with which the official discourse perceived the first years of design practice formation after the cultural policy change in 1952; the critique was used to justify changes.**key=108** Prior to the conference, Václav Hilský published the article “Reflection on the Architects’ Conference”,**key=109** in which he not only describes expectations, but also calls for the conference to be used to take a critical look at post-war architectural work and its organization: “It is convenient to understand architecture as the economic production of design drawings … The formation of our socialist design sector was guided by an attitude of hatred towards architecture, and even towards creative architects themselves, who were already drawing attention to this mistake at that time.”**key=110** One of the documents circulated at the conference was the “Document on the Establishment and Development of the Socialist Design Sector”, which, echoing Hilský’s words, expressed dissatisfaction with the diminishing importance of the creative component of architectural work in the current practice.**key=111**

Dissolution of the Central Directorate

Stavoprojekt’s existence as a state institute under the Ministry of the Interior was short-lived. On 23 June 1953,**key=112** the Minister of Local Economy Jozef Kyselý ordered the dissolution of the Stavoprojekt Directorate with effect from 1 January 1954.**key=113** Its activities were taken over by the Main Administration of Design Institutes under the Ministry of Local Economy, with Otakar Štaudigl becoming its head.**key=114** Each regional design center both in the Czech and the Slovak territory thus became an autonomous state institute. Altogether, 19 regional state design institutes emerged, now operating under the name State Institute for Urban and Rural Construction [Státní ústav pro výstavbu měst a vesnic].**key=115** This essentially fulfilled the initial demands raised by part of the architectural community at the beginning of 1948 for the establishment of dislocated national ateliers as an independent body.

The regional design institutes underwent several organizational changes after 1954,**key=116** but despite the changing designations, their structure remained essentially unchanged until 1989.**key=117** Alongside the regionally affiliated ones, further design institutes were established within the industry-oriented ministries or became independent of the formerly statewide Stavoprojekt institute. One significant example was for instance the State Institute for the Reconstruction of Historic Towns and Buildings in Prague [Státní ústav pro rekonstrukce památkových měst a objektů – SÚRPMO], which seceded from Stavoprojekt in 1954.**key=118**

Conclusion

Stavoprojekt represents an attempt to create a centrally managed design enterprise on a national scale – an ambition of enormous proportions. In retrospect, the former deputy director, Otakar Nový, believed that Stavoprojekt was probably “before 1954, the largest [single] design organization in the world, with 11,000 employees.”**key=119** However, from the outset, its various components began to split up geographically and by specialization, although all its parts were at least in theory supposed to cooperate closely. The end of central management by the Prague-based Directorate was probably also related to the rapidly changing cultural-political milieu in Czechoslovakia at the beginning of the 1950s. The process of Sovietization**key=120** was accompanied by instability and was not exclusive to Stavoprojekt – rapid change was also taking place at the level of state authorities.**key=121** However, the extent to which the organizational changes marking the beginnings of Stavoprojekt were reflected in everyday architectural work remains a question for further research, which this paper aims to facilitate.

Based on the analysis of archival materials and literature, this text outlines the first stage of the institute’s existence, which laid the foundations for the next four decades of architecture and centralized planning. Although Stavoprojekt existed as a single joint institution for only a short time, it established the institutional foundations of design, building research, and standardization for the entire post-war period. Following the dissolution of its Directorate in the mid-1950s, the centrally planned economy and rampant bureaucracy and technocracy were only just beginning. As they grew to larger proportions, architects gradually resorted to seeking alternative ways to express their creative ideas.**key=122** The legacy of Stavoprojekt and other design institutes operating in the former Czechoslovakia between the 1940s and 1989 lies not only in their material manifestation in the built environment, but also in how they shaped the self-perception of the architectural profession.

This paper was written as the outcome of the grant Stavoprojekt 1948–1953. Collectivization of Architectural Designing and Its Imprint in the Memory of Czech Landscape and Cities (Project no. DH23P03OVV004, principal investigator: Petr Vorlík) supported by the NAKI III programme of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic

Mgr. art. Lucia M. Tóthová, PhD.

orcid: 0009-0001-4108-4357

Klára Ullmannová, MA

orcid: 0009-0009-5813-1533

Faculty of Architecture

Czech Technical University in Prague

Thákurova 9

166 34, Prague 6

Czech Republic

lucia.mlyncekova@fa.cvut.cz

klara.ullmannova@cvut.cz

ZIKMUND, Jan. 2019. Co je to? Má to dvě kola a dvě brzdy a přece včas dojede. In: Dvořáková, D., Guzik, H. and Zikmund, J. Architektura v přerodu: 1945–1948, 1989–1992. Prague: Czech Technical University (hereinafter CTU) in Prague, Faculty of Architecture, pp. 16–33.

Project MK ČR NAKI III DH23P03OVV004 Stavoprojekt 1948–1953. Stavoprojekt 1948–1953. Collectivization of Architectural Designing and its Imprint in the Memory of Czech Landscape and Cities. Principal investigator Prof. Ing. arch. Petr Vorlík, Ph.D., Faculty of Architecture, Czech Technical University in Prague, Department of Theory and History of Architecture.

Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

KNAPÍK, Jiří. 2004. Únor a kultura: sovětizace české kultury 1948–1950. Prague: Libri; KNAPÍK, Jiří. 2006. V zajetí moci: kulturní politika, její systém a aktéři 1948–1956. Prague: Libri.

RUSINOVÁ, Zora (ed.). 2000. Dejiny slovenského výtvarného umenia: 20. storočie. Bratislava: Slovak National Gallery; PETIŠKOVÁ, Tereza. 2002. Československý socialistický realismus 1948–1958. Prague: Galerie Rudolfinum; ŠVÁCHA, Rostislav and PLATOVSKÁ, Marie (eds.). 2005. Dějiny českého výtvarného umění V. 1939–1958. Prague: Academia.

AMAN, Anders. 1992. Architecture and Ideology in Eastern Europe During the Stalin Era: An Aspect of Cold War History. New York: Architectural History Foundation; DULLA, Matúš and MORAVČÍKOVÁ, Henrieta. 2003. Architektúra Slovenska v 20. storočí. Bratislava: Slovart; MILJAČKI, Ana. 2017. The Optimum Imperative: Czech Architecture for the Socialist Lifestyle, 1938–1968. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; SKŘIVÁNKOVÁ, Lucie, ŠVÁCHA, Rostislav and LEHKOŽIVOVÁ, Irena (eds.). 2018. The Paneláks: Twenty-Five Housing Estates in the Czech Republic. Prague: Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague; HALÍK, Pavel. 2022. Česká architektura 50. let: studie o střetu funkcionalismu a konstruktivismu s ideovými východisky socialistického realismu. Prague: Pulchra.

MAIER, Karel and ŠLEMR, Jan. 2016. Theory and Reality of Czech and Slovak Urban and Spatial Planning since 1945. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 50(3–4), pp. 164–179.

KURZ, Michal. 2023. Vize a budování socialistických měst v období stalinismu (Praha 1948–1956). PhD thesis. Charles University, Faculty of Arts.

OLŠÁKOVÁ, Doubravka and JANÁČ, Jiří. 2018. Kult jednoty. Stalinský plán přetvoření přírody v Československu 1948–1964. Prague: Academia.

GUZIK, Hubert. 2014. Čtyři cesty ke koldomu: kolektivní bydlení – utopie české architektury 1900–1989. Prague: Zlatý řez; ZIKMUND, Jan. 2020. Hledání univerzality: kontexty průmyslové architektury v Československu 1945–1992. Prague: CTU in Prague, Research Center for Industrial Heritage of the Faculty of Architecture.

JANEČKOVÁ, Michaela. 2020. Energetismus jako prostředek zvědečtění architektury v knize Karla Janů Socialistické budování. Sešit, (28), pp. 37–55.

VYMĚTALOVÁ, Martina and GORYCZKOVÁ, Naďa (eds.). 2002. Poválečná totalitní architektura a otázky její památkové ochrany: sborník příspěvků: mezinárodní seminář. In: Poválečná totalitní architektura a otázky její památkové ochrany. Státní památkový ústav, Ostrava 18–19 September 2002. Ostrava: State Heritage Institute Ostrava; SEDLÁKOVÁ, Radomíra. 1994. Sorela – česká architektura padesátých let [exhibition catalogue]. Prague: National Gallery Prague.

ZARECOR, Kimberly Elman. 2015. Utváření socialistické modernity. Bydlení v Československu v letech 1945–1960. 1st edn. Prague: Academia; originally ZARECOR, Kimberly Elman. 2011. Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity: Housing in Czechoslovakia, 1945–1960. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

KOTKIN, Stephen. 1997. Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zikmund, J., 2019, p. 21.

STORCH, Karel. 1945. Cesta k zprůmyslnění stavebnictví. Architektura ČSR, 5(2), pp. 40–46.

See e.g. HONZÍK, Karel and HAVLÍČEK, Josef. 1930. Odpověď na anketu Tvorby. Tvorba, 5(24), pp. 374–375, 383; and further ZUZAŇÁKOVÁ, Martina. 2006. Utopie avantgardy. Kolektivní dům v meziválečném Československu. Master’s thesis. Masaryk University, Faculty of Arts. Available at: https://is.muni.cz/th/oq043/diplomova_prace.pdf (Accessed: 18 February 2025).

BAPS and the architectural situation in the immediate post-war period are discussed in detail in: Zarecor, K., 2015, pp. 45–53.

GUZIK, Hubert. 2019. Plánovači, sociologové a průzkumy veřejného mínění. In: Dvořáková, D., Guzik, H. and Zikmund, J. Architektura v přerodu: 1945–1948, 1989–1992. Prague: CTU in Prague, Facuty of Architecture, pp. 34–61.

STARÝ, Oldřich. 1945. Spolupráce architektů na výstavbě státu. Architektura ČSR, 5(1), p. 2; Architektura ČSR. 1947. Návrh BAPS na vymezení působnosti ministerstva techniky a organisace jeho jednotlivých oborů. Architektura ČSR, 6(3), p. 67.

NOVÝ, Otakar. 1949. Nová organisace projekční práce. Architektura ČSR, 8(1), pp. 53–56.

“Situační zpráva Stavoprojektu”, 21. 1. 1949, s. 5. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

PAVEL, Miroslav. 2025. Mezi státem a institucí. In: Vorlík, P. (ed.) Stavoprojekt 1948–1953 / praxe [manuscript in preparation]. Prague: CTU Prague, Faculty of Architecture; Act no. 121/1948 coll., on the nationalization in the construction industry.

Act no. 121/1948 coll., on the nationalization in the construction industry.

Decree of Ministry of Technology no. 1166/1948 (Úřední list), on the establishment of “Czechoslovak Building Works, a national enterprise” with its registered office in Prague.

Ústřední akční výbor architektů ČSR. 1948. Prohlášení ústředního Akčního výboru architektů ČSR. Architektura ČSR, 7(3), p. 42.

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. architektů. 1955. Prague: Union of Czechoslovak Artists – Union of Architects, Czech Fund of Visual Arts, p. 262.

“Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p.”, STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague); “Zápis z druhé porady vedoucích všech oddělení Stavoprojektu v Čechách, konané dne 7. 10. 1948 v Praze”, p. 5. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

“Zápis z druhé porady vedoucích všech oddělení Stavoprojektu v Čechách, konané dne 7. 10. 1948 v Praze”, p. 4. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. architektů. 1955. Prague: Union of Czechoslovak Artists – Union of Architects, Czech Fund of Visual Arts, p. 265–274.

NOVÝ, Otakar. 1973. Čtvrtstoleté jubileum založení Stavoprojektu. Architektura ČSR, 32(10), pp. 483–490.

Nový, O., 1973, p. 488.

Already in internal documents from 1949, greater emphasis was placed on subordinating the coordination of design ateliers to the needs of “construction production”. Organisační směrnice Stavoprojektu, účinnost 1. 5. 1949, s. 3–5. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. architektů. 1955. Prague: Union of Czechoslovak Artists – Union of Architects, Czech Fund of Visual Arts, p. 263.

Stavoprojekt was never the sole design organisation in the country. Even in the years 1948–1953, several other design offices operated alongside it, primarily within large industrial enterprises or ministries (e.g. Energoprojekt, Chemoprojekt, Kovoprojekta). Návrh státního katalogu prací technických pro projekční službu, s. 2. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Zikmund, J., 2019, p. 22.

Pavel, M., 2025; Decree no. 63/1945 coll. Decree of the President of the Republic on the Economic Council.

KOUŘIL, Miroslav. 1948. Architekti a sjezd národní kultury. In: Kouřil, M. (ed.). Sjezd národní kultury 1948. Sbírka dokumentů. Prague: Orbis, pp. 44–45.

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. Architektů, 1955, p. 268. The Soviet system of architectural institutionalization was published in Czechoslovak periodicals e.g. in: ARKIN, David. 1948. Organisace architektonické činnosti v SSSR. Architektura ČSR, 7(3), p. 82.

Architektura ČSR. 1948. Architektonická rada Stavoprojektu. Architektura ČSR, 7(9),

[not paginated].

The members of the Stavoprojekt Architectural Council were: Jiří Kroha, Ferdinand Balcárek, Adolf Benš, František M. Černý, Bohuslav Fuchs, Kamil Gross, Josef Grus, Václav Hilský, Jaroslav Pokorný, Václav Roštlapil, Karel Štorch, Jiří Štursa, Jiří Voženilek. Seznam členů architektonické rady. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. Architektů, 1955, p. 272.

For further context, see: Zarecor, K., 2015, pp. 126–131.

A detailed account is provided for instance by DVOŘÁKOVÁ, Dita. 2017. The Czech Discourse on Regional Planning Between 1945 and 1948. Architektúra & urbanizmus, 51(3–4), pp. 144–161.

Zarecor, K., 2015, p. 126.

Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

“Zápis porady vedoucích arch. atelierů na Moravě a zástupců ředitelství Stavoprojektu, konané dne 22. října 1948 v Ostravě”, p. 5. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

See e.g. Storch, K., 1945, pp. 40–46; see also “Zápis z porady vedoucích arch. atelierů na Moravě a zástupců ředitelství Stavoprojektu, konané dne 22. října 1948 v Ostravě”, p. 4. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Act no. 280/1948 coll., on the establishment of regions.

Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

“Zápis z porady vedoucích arch. atelierů na Moravě a zástupců ředitelství Stavoprojektu, konané dne 22. října 1948 v Ostravě”, p. 4. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Státní úřad plánovací, Směrnice pro vypracování návrhu výrobního plánu projekčních prací stavebních na II. pololetí R. 1950, Praha 1950. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

However, even at this time the ambition was that the merger would be temporary, just as the absolute centralization of the enterprise. See ZELINKA, Rudolf. 1948. Organisace znárodněného stavebnictví. Stavebnictví, 4(4), pp. 49–52.

Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Směrnice č. 1 pro vybudování oddělení Stavoprojektu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, září 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

VOŽENÍLEK, Jiří. 1949. Zásada a organizace urbanistické práce ve Stavoprojektu. Architekt: měsíčník pro architekturu a urbanismus, 46(10), pp. 162–164.

See ZARECOR, Kimberly Elman. 2007. Stavoprojekt a Ateliér národního umělce Jiřího Krohy v 50. letech 20. století. In: Dvořáková, D. and Macharáčková, M. (eds.) Jiří Kroha (1893–1974) architekt, malíř, designér, teoretik v proměnách umění 20. století. Brno: Brno City Museum, pp. 328–365; and Zarecor, K., 2015, pp. 232–289.

Zarecor, K., 2007, pp. 328–365.

Dopis Doručený: sekretariát kraj. Výboru Praha, k rukám s. Vomastka, tajemníka NHK, Praha Hybernská ul., 21. 9. 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dopis Doručený: sekretariát kraj. Výboru Praha, k rukám s. Vomastka, tajemníka NHK, Praha Hybernská ul., 21. 9. 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dopis Doručený: sekretariát kraj. Výboru Praha, k rukám s. Vomastka, tajemníka NHK, Praha Hybernská ul., 21. 9. 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dopis Doručený: sekretariát kraj. Výboru Praha, k rukám s. Vomastka, tajemníka NHK, Praha Hybernská ul., 21. 9. 1948. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

For example, the office of the Prague regional architectural atelier was at the same address as the apartment of its director Josef Havlíček (Šmeralova 21); the same principle applies to the Prague branch office of the Ústí nad Labem regional atelier (located the address of architect Václav Hilský at Tychonova 10). Adresář ředitelství a všech oddělení Stavoprojektu. 12. 1. 1949. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

See e.g. Stavoprojekt. 1952. Zdokonalená spolupráce vedoucího s oddělením. Stavoprojekt – závodní časopis závodu Stavoprojekt v Ostravě, 1(6), 12 November, [no pagination].

Stav projekční činnosti v okamžiku znárodnění, 18. 3. 1949. s. 1. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Stav projekční činnosti v okamžiku znárodnění, 18. 3. 1949. s. 2. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Návrh zjednodušené organisace závodu, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, nedat. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Organisační směrnice (účinnost od 1. 5. 1949), Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Situační zpráva Stavoprojektu, 6. 7. 1949, Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Nový, O., 1949, p. 54.

It probably continued the work of the Moravian-Silesian Provincial Institute of Planning and Studies. See e.g. MRKOS, Josef and HRUŠKA, Emanuel (eds.). 1946. Přehled grafických prací Zemského studijního a plánovacího ústavu v Brně zpracovaných do konce roku 1946. Zprávy Zemského studijního a plánovacího ústavu v Brně, 1(1), pp. 5–7.

Organisační směrnice (účinnost 1. 5. 1949), Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

At this point, there was also consideration of a studio in Zvolen (in archival documentation, it is repeatedly referred to as Zvoleň), despite Banská Bystrica being the regional capital (where the studio was established later). Organisační směrnice (účinnost 1. 5. 1949), Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Stav zaměstnanců k 2. 7. 1949. Československé stavební závody, n.p., STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Organisační řád STAVOPROJEKTU, STAVOPROJEKT ředitelství, Praha, prosinec 1950. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Pavel, M., 2025.

Government decree no. 60/1951 coll., extending the validity of the Act on National Industrial Enterprises to national enterprises in the field of the construction industry.

Government decree no. 159/1950, decree of 19 December 1950 changing the number and scope of ministries.

Pavel, M., 2025.

Organizační řád – Směrnice č. 3, platí od 13. 6. 1951. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Organizační řád – Směrnice č. 3, platí od 13. 6. 1951. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Zřizovací listina národního podniku, 22. 10. 1951. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Zprávy a pokyny pro likvidaci ČSSZ. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Act no. 58/1951 coll., amending and supplementing the Act on nationalization in the construction industry. Act no. 121/1948 coll. on the nationalization in the construction industry.

Pověření vedením, v Praze dne 22. 10. 1951. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

See e.g. NOVÝ, Otakar and PROCHÁZKA, Vítězslav. 1987. VÚVA – Výzkumný ústav výstavby a architektury, 1952–1987. Brno: VÚVA Brno.

On Rudolf Slánský, see e.g. TOMEŠ, Josef et al. 1999. Český biografický slovník XX. století. Prague, Litomyšl: Paseka, 649 p.

KNAPÍK, Jiří. 2011. Slánština. In: Knapík, J. and Franc, M. (eds.). Průvodce kulturním děním a životním stylem v českých zemích 1948–1967. Vol. II. Prague: Academia, pp. 831–832. See also KNAPÍK, Jiří. 2006. V zajetí moci: kulturní politika, její systém a aktéři 1948–1956. Prague: Libri, p. 153.

Knapík, J., 2011, p. 831.

Knapík, J., 2011, p. 832.

Nový, O., 1973, pp. 488–489.

Official architectural periodicals also published speeches from a conference of architects’ delegates in which the “Slánský clique” was even blamed for shortcomings in the construction industry and delays to the investment plan. STARÝ, Oldřich. 1953. Kupředu za socialistickou ideovost, za umělecké mistrovství, za vyšší ekonomii české a slovenské architektury. Architektura ČSR, 12(5–7), pp. 107–137.

Prozatimní statut národních podniků stavebních (vydaný v příloze výnosu ministra stavebního průmyslu ze dne 22. 11. 1952 čj. 720.9/16-Koord. l/Zu-52). Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Prozatimní statut národních podniků stavebních (vydaný v příloze výnosu ministra stavebního průmyslu ze dne 22. 11. 1952 čj. 720.9/16-Koord. l/Zu-52). Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Prozatimní statut národních podniků stavebních (vydaný v příloze výnosu ministra stavebního průmyslu ze dne 22. 11. 1952 čj. 720.9/16-Koord. l/Zu-52). Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Government Decree no. 28/1952 coll., decree of 8 July 1952 on project and budget documentation of investments.

Government Decree no. 28/1952 coll., decree of 8 July 1952 on project and budget documentation of investments.

Sdělení střediskům: reorganizace Stavoprojektu n. p. v Praze na Státní ústav pro projektování sídlišť a pozemních a inženýrských staveb „Stavoprojekt“, 12. 1. 1953. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Pavel, M., 2025.

Jmenování ředitele, 30. 6. 1953. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Stavoprojekt n. p., nová organizace, 13. 1. 1953. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Převod Stavoprojektu z resortu MSP do resortu MV, 2. 7. 1953. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague); Národní archiv ČR. Státní projektový ústav Stavoprojekt – převedení do působnosti ministerstva vnitra, 25. 7. 1953. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Replaced by Rudolf Barák in September 1953. See NIKLÍČEK, Ladislav. 1994. Rudolf Barák. In: Churaň, M. et al. (eds.). Kdo byl kdo v našich dějinách 20. století. Prague: Libri, pp. 16–17.

Referát k celostátní konferenci funkcionářů Státního projektového ústavu Stavoprojekt dne 24. 7. 1953 v Národním klubu. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. Architektů, 1955.

HILSKÝ, Václav. 1953. Úvaha o konferenci architektů. Architektura ČSR, 12(1–2), pp. 20–21.

Hilský, V., 1953, pp. 20–21.

Dokumenty I. celostátní konference delegátů čs. Architektů, 1955, pp. 257–275.

Government Decree no. 57/1953 coll., decree of 23 June 1953 on the competence of the Ministry of the Interior in the field of spatial planning and construction of municipalities and in the field of care for technical services of national committees.

Příkaz ministra místního hospodářství k záhájení reorganizace projektových ústavů v resortu ministerstva místního hospodářství, 21. 12. 1953, Věstník Hlavní správy projektových ústavů, č. 1, 1954. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

Věstník Hlavní správy projektových ústavů, č. 1, 1954. Fund ČSSZ – Stavoprojekt [unprocessed]. National Archives (Prague).

KUNA, Zdeněk et al. 1978. Vznik a 30 let práce socialistických projektových organizací v ČSSR, 1948–1978. Prague: The Federal Union of Architects of Czechoslovakia, p. 14.

See e.g. TÓTHOVÁ, Lucia. 2023. (Vý)Stavoprojekt Trnava, Trenčín, Piešťany. Trenčín: Projekt Hlava V.

Tóthová, L., 2023, p. 31.

NĚMEC, Josef. 1984. Třicet let práce SÚRPMO 1954–1984 [exhibition catalogue]. Brno: SÚRPMO and Brno Technical Museum, [no pagination].

Nový, O., 1973, pp. 488–489.

KNAPÍK, Jiří. 2004. Únor a kultura. Sovětizace české kultury 1948–1950. Prague: Libri, 360 p.

Nový, O., 1973, pp. 488–489.

See e.g. KRAJČI, Petr and VORLÍK, Petr. (eds.) 2020. Navzdory: architekti 1969–1989–2019. Prague: Grada; VORLÍK, Petr and ZIKMUND, Jan. (eds.). 2021. Improvizace / Architektura osmdesátých let. Prague: CTU in Prague, Faculty of Architecture.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2025.59.1-2.8

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License