The legacy of Hungarian historicist architecture has only attracted the attention of researchers in the past few decades. Although the Renaissance and Baroque Revival were the dominant architectural styles of the Habsburg era, historicism was long seen as an architecture copying the past using cheaper materials. Characterized by the reinterpretation of historical styles with contemporary materials, the use of classical architectural details, and sculptural ornamentation, historicism defines the image of Budapest’s city center, including the Grand Boulevard of the Pest side, which was built in the last three decades of the 19th century.

The urban significance of the Grand Boulevard is unquestionable, creating a whole new urban structure worthy of a metropolis. In my study, I intend to examine the urbanistic significance of the historicist architectural heritage of the Grand Boulevard, and how these imposing buildings affect the urban landscape. To find the answers, I will look at the most important public buildings on the Boulevard, including the Nyugati pályaudvar [Nyugati Railway Station], the Vígszínház [Comedy Theatre], and the Népszínház [People’s Theatre] – later Nemzeti Színház [National Theatre] – on Blaha Lujza Square. I would also like to discuss the less prominent historicist apartment palaces, their typical ground plans and architectural characteristics, which equally contribute to the image of the Boulevard and the Hungarian capital.

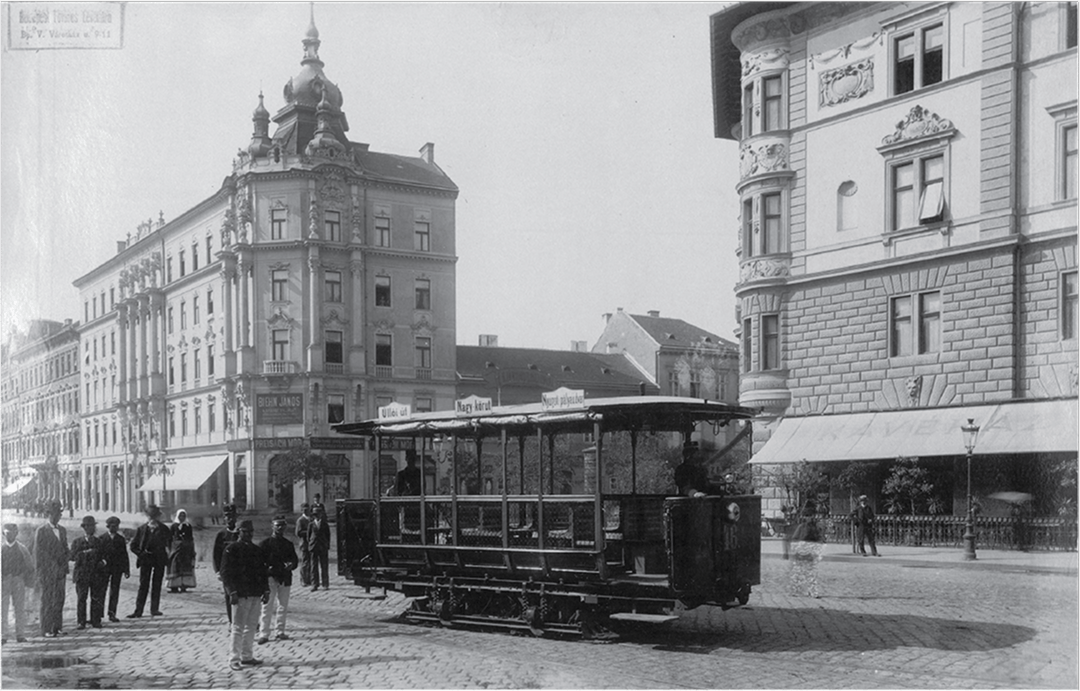

The construction of the Nagykörút [Grand Boulevard] – is the most significant element of 19th-century urban planning in the newly united Budapest. Replacing the capital’s previous cramped street structure with a clearer, transparent one, it paved the way for the development of urban landscape and infrastructure in the same way as Paris and Vienna, among other European metropolises. The boundaries of the urban core were extended further, and redevelopment began of the once-suburban, industrial areas affected by the boulevard. Several public buildings were erected along the route, which raised its status, and the Pest side of the boulevard was built up with four- and five-storey apartment blocks.

The image of the Hungarian capital is still largely determined by the urban planning ideas of the 19th century, just as the typical building of Budapest has remained the historicist urban apartment block, where the individual units are accessed from an open corridor running along the courtyard façades.

This study focuses primarily on the urban significance and historicizing architecture of the Nagykörút, but also examines what patterns are manifested, whether international or specifically Hungarian.

The Grand Boulevard in the Urban Structure of Budapest – Research History

The Nagykörút is one of the most important elements of Budapest’s urban structure and has therefore played a significant role in the research and literature on urban planning of the capital. In this context, it is worth mentioning the works of engineer Aladár Edvi-Illés (1858–1927) and architect Gábor Preisich (1909–1998). The technical guide by Edvi-Illés was an early treatment of the history of urban development, completed to mark the millennial anniversary of the Hungarian state’s founding in 1896.1 In the middle of the 20th century, Preisich reviewed the urban architecture of Budapest from the recapture of Buda from Ottoman rule in 16862 up until the 1990s3 in a series of volumes. In the second volume of the series, he dealt with the development of the urban fabric of the post-1867 period of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, of which the construction of the Grand Boulevard in Budapest was a significant development.4 His volumes have also been published in new editions by the publisher TERC,5 and several researchers have worked on the subject. Among them, the studies of Péter Hanák6 and Ferenc Vadas7 are worth highlighting, the latter writing on the urban development of Budapest in a volume published jointly by the Viennese and Budapest archives, which analyses the structural and infrastructural developments of the two cities in parallel. For further research, it is worth highlighting the works of Máté Tamáska8 and Dezső Ekler, who analysed the boulevards of various cities, including Vienna, Budapest and Szeged.9 The names of Judit N. Kósa10 and Rezső Ruisz11 are worth mentioning in connection with research on the Nagykörút.

In addition to the works mentioned above, there are several others that deal with the architectural significance of the boulevard. These include monographs of architects, in which several buildings are described, or the presentation of building types, for example Mihály Kubinszky’s volume on railway stations in connection of the Nyugati Railway Station,12 Zsuzsa Körner’s,13 or Éva and Miklós Lampel’s volume on tenement houses.14 However, the subject deserves further research, as it has a rich architectural heritage, many details of which remain unexplored.

Urban Development in Budapest in the 19th Century

Although urban planning efforts were already underway in the second half of the 18th century, with the creation of the new suburbs of Terézváros and Józsefváros, named in 1777 after Maria Theresia and Josef II; later, in 1792, the part of Józsefváros closer to the Danube became an independent district, Ferencváros, named after Francis II.

The regulation continued in the early 19th century. It was primarily marked by Archduke Joseph (1776–1847), Palatine of Hungary between 1796 and 1847, who, with the architect József Hild (1789–1867), prepared the regulatory plan for the Pest side.15 This plan mainly focused on the old city center, Lipótváros, but not as generously as later designs. The inventions of Hild, in addition to the aesthetic plan agreed upon in 1808, also included creation of a sewage system and road paving.16

Reconstruction after the great flood of 1838 brought more new buildings than significant changes to the urban structure, and the turbulent political situation between 1848 and 1867 temporarily halted major urban development. In 1846, the first Hungarian railway line opened and the Indóház – the classicist railway station building designed by Wilhelm Paul Eduard Sprenger (1798–1854) and Mátyás Zitterbarth (1803–1867)17 – was built in Pest on the site of today’s Nyugati Railway Station.18

Larger-scale town-planning plans had already been drawn up in the years before Hungary achieved meaningful autonomy after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, as the engineer Ferenc Reitter (1813–1874) had already come up with a plan for a circular canal in 1865, which would have offered an alternative to the future boulevards.19 Together with Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy (1823–1890, in office: 1867–1871), Reitter also drew up the program of the Public Works Council [Közmunkatanács], which was established in 1870 specifically to plan urban regulation. The plans, which would be adapted at a later phase, were to be procured through an international design competition in 1871. Already included in the call, the boulevards and avenues were mainly inspired by the urban planning of Georges Eugène Haussmann (1809–1891) in Paris, realized between 1853 and 1870. The first prize was won by Lajos Lechner (1833–1897), the second by Frigyes Feszl (1821–1884), and the third by Klein and Fraser. In the end, the Közmunkatanács drew up the final plan in 1872.20

The largest-scale reorganization of the former urban structure took place after the unification of Pest, Buda, and Óbuda in 1873. Terézváros, Józsefváros, and Ferencváros, the suburbs founded in the 18th century, were elevated to the level of central districts, and subjected to further division, with the 7th District – named in 1882 Erzsébetváros after Empress Elisabeth –separated from the 6th District, Terézváros. However, larger-scale works were somewhat hampered by the stock exchange crisis of the year 1873.

Meanwhile, the Sugárút, or Avenue, now Andrássy Street, was built, with the Avenue Construction Company [Sugárúti Építő Társaság] in charge of the works. The old houses on the route were demolished between 1871 and 1875, but the company went bankrupt during the economic crisis and from 1876 the Közmunkatanács took over the route, which opened that year. This was the most exclusive of the new roadways of the capital. In addition to the avenue, the construction of three boulevards was a central element. The shorter, the Kiskörút [Little Boulevard] is situated in the old city center of Pest, though built along existing routes; it consisted of the Károly körút, Múzeum körút, and Vámház körút. The largest and outermost, the Hungária körgyűrű, was only completed in a later phase.21

The most significant boulevard is the Nagykörút, linking the former suburbs. It also took longer to build, as it was only opened in 1896 on the Pest side, and took ten more years to complete with buildings. Additionally, the construction of the boulevard required numerous expropriations and demolitions. It has 253 buildings, mostly residential, though with several public buildings. Apartment buildings were built on the re-parceled plots, less elegant compared to Andrássy út, but of greater commercial importance. Cafes and shops opened at the bottom of the buildings, while theaters, hotels, and banks were built for the cultural, financial, and touristic life of the capital. The route was characterized by significant pedestrian traffic and economic activity. From this point of view, it is similar to the Grand Boulevard of Paris; contrastingly, the Ringstraße in Vienna provides a more elegant route, like Andrássy út in Budapest.

Each section of the boulevard is named after the part of the city where it is located, hence Ferenc körút, József körút, Erzsébet körút, Teréz körút and Lipót körút, though the last section now bears the name of Szent István körút, after Stephen I of Hungary.

Although the continuation of the boulevard into Buda was also on the agenda at the same time as the side of Pest, the two roadways were able to develop at different rates. Largely following the route of the former Országút but of later construction, it consists of the sections Margit körút and Krisztina körút. Still, the latter is more of an avenue, as it connects Margit körút diagonally with the Elisabeth Bridge, whose predecessor was built in 1903. Likewise, the style of the buildings is different on the Pest side and the Buda side corresponding to their different ages. While on the Buda side trends following the turn of the century are typical, the Nagykörút in Pest shows a completely historicist picture, apart from a few examples built in the 20th century.

Historicist Architecture in Hungary and Its Appearance on the Nagykörút

Before turning to the historic buildings of the Nagykörút, it is important to clarify the concept of historicist architecture in Hungary.

The earlier architectural trends of the 19th century, such as classicism and romanticism, were themselves inspired by historical styles – ancient and medieval. The Neo-Renaissance, which appeared in Hungary in the 1860s following the work of Miklós Ybl, equally fit into this line. Ybl’s early Neo-Renaissance buildings were the Savings Bank Palace in Buda (Budapest I. Fő utca 2, 1860–1862, demolished) and the palace of György Festetics (Budapest V. Ötpacsirta utca 17, 1862–1865) behind the National Museum, in the Palotanegyed [Palace District] adjoining the old city center.

The Neo-Renaissance movement drew upon on the Italian Renaissance, primarily Venetian and Florentine architecture. The phenomenon was born from the rediscovery and research of architecture of earlier ages, in which France was at the forefront, and thus the originator of the trend. Indeed, it is through to the work of French researchers like Antoine-Nicolas Dezallier d’Argenville (1723–1796) that we use the French word “Renaissance” instead of the Italian “Rinascimento”.22 In the mid-19th century, French and then German albums of the architecture of the Italian Renaissance were published, providing architects with models.23 The study of Renaissance buildings was also served by the study trips to Italy made by most of the qualified architects of historicism.24

In the early 1880s, Neo-Baroque architectural influence arrived from Vienna, mostly through Arthur Meinig (1853–1904), a former colleague of the architectural office of Ferdinand Fellner (1847–1916) and Hermann Helmer (1849–1919), credited with one of the first Neo-Baroque buildings in Vienna, the Sturany Palace (1878–1880).25 Meinig came to Budapest in connection with the construction of the Károlyi-Csekonics Palace (Múzeum utca 17, 1881–1883), an early Neo-Baroque building in Budapest by Fellner and Helmer, and later followed the same line himself.26 Like the Neo-Renaissance, the emergence of the Neo-Baroque is the result of research and reassessment of the architecture of the 19th century. Its most important personalities were the German-speaking art historians Albert Ilg (1847–1896), Cornelius Gurlitt (1850–1938), August Schmarsow (1853–1936), and Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945). Gradually, the Neo-Baroque style assumed national status within Austria, given that the castles of the ruling family were largely built in this epoch, with the Baroque given special preference Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand (1863–1914).27 Hence it is no surprise that the Neo-Baroque spread throughout the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

As the Neo-Baroque became integrated, in turn, into Hungarian historicism, from then on appeared on buildings in parallel with the Renaissance, or more frequently mixed with it, forming a style often referred to as eclecticism.28 In addition to Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque, the evocation of medieval, Gothic, Romanesque, and Byzantine forms was also present, primarily in church buildings. Some artists, such as Imre Steindl (1839–1902), Frigyes Schulek (1841–1919), and Samu Pecz (1854–1922), applied medieval motifs to a wider spectrum of buildings, and others, such as Henrik Schmahl (1849–1912), were also fond of using elements of Moorish architecture.29

Historicism was an international tendency in the second half of the 19th century, so it was not only in Hungary, but in all the countries of Central and Western Europe, where a remarkably similar approach to architecture dominated. However, temporal differences were evident in the chronology of the appearance of the styles. Then, from the 1890s onwards, individual, and national architectural movements began to emerge, which wanted to break away from historical forms. Nonetheless, historicism long continued to play a leading role and even returned in the years following the First World War.

While Austria and the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy generally followed the Neo-Baroque style, Hungary also sought the historical style that best suited the nation. Although this was mostly seen in a medieval-inspired, especially neo-Gothic, direction, it was eventually Neo-Renaissance and (a little less) Neo-Baroque that became the dominant architectural style in the country. These idioms were most in keeping with the taste of the liberal governing party ruling for most of the late Habsburg era. Representative thoroughfares, such as the Nagykörút, and major public buildings of Budapest were given special attention, with the government party adhering consistently to its stylistic ideas. In 1902, for example, Gyula Wlassics (1852–1937) rejected Ödön Lechner’s (1845–1914) experiments in national style and demanded their omission from state buildings.30 Despite its lack of popularity among the government and the architects with conservative taste, among the innovative movements the Viennese Secession achieved its place in the oeuvre of the supported architects of the period, for example, Ignác Alpár (1855–1928) and Győző Czigler (1850–1905).

In line with the tendencies outlined above, the buildings of the Nagykörút are also mostly Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque. Among the innovative trends, the Viennese Secession – inspired by the works of Otto Wagner (1841–1918) – was able to play a role in a few buildings, for example, the Amon (Szent István körút 12, 1900) and Weiss apartment blocks (Szent István körút 4, 1904) by Géza Aladár Kármán (1871–1939) and Gyula Ullmann (1872–1926). Influences of Viennese Secessionism or Art Nouveau are most prevalent on Szent István körút, while the dominance of historicism, with a few exceptions, is almost unanimous in the other sections.

The architecture of the boulevard essentially covers almost three decades of Hungarian historicism and turn-of-the-century architecture. The first buildings – the house of István Mendl by Alajos Hauszmann (48 József körút 48) and the house of Karolina Hebelt-Deák by Antal Dörschung (József körút 50) – were constructed in 1872–1873 and in the age of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy the last building, already discernibly Secessionist, is the house of Sándor Pollák by Dávid Jónás (Ferenc körút 19–21) from 1905–1906.31 In between, the styles range from Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, Eclectic, and Art Nouveau. Later periods have also left their mark on the buildings, so the remodeling of the portals and the arcading of the ground floor of some buildings reflect the taste of the 1950s. More recent buildings have also been added, such as the building of the Madách Theater, designed by Oszkár Kaufmann (1873–1956) and built in 1961, and the office building at Teréz körút 50 by József Finta (1935–2024) in 2009. However, these exceptions do little to shift the image of the boulevard as essentially historicist.

Historicist Public Buildings on the Nagykörút

Several public buildings are located along the Nagykörút, of which the Nyugati Railway Station and two theatres, the Népszínház [People’s Theatre], and the Vígszínház [Comedy Theatre] date back to the Dual Monarchy.

A common feature of the public buildings on the Nagykörút is that they are all the work of internationally renowned architecture studios, and belong to important trends of historicism. The Nyugati Railway Station was built by the firm of Gustave Eiffel (1832–1923) from Paris, and the two historicist theatres, the Népszínház and the Vígszínház were designed by the Viennese architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, who designed nearly fifty theatres in Europe.32 In Hungary, Fellner and Helmer’s works are the Somossy Orfeum (1893–1894), now the Budapest Operetta Theatre [Budapesti Operettszínház] the theatres in Szeged (1882–1883), and Kecskemét (1895–1896), and the former Castle Theatre in Tata (1888–1889, demolished in 1913). They designed the Károlyi-Csekonics Palace (Múzeum utca 17, 1881–1883) and the Rothberger Warehouse in Budapest (Váci utca 6, 1909–1910, highly modified), and the Solymosy-Gyürky Castle in Szőny (1911–1913). Their architecture is characterized by elements of Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, and, thanks to Fellner’s son, Ferdinand Fellner Junior, who once worked for Victor Horta, even a certain influence of the Belgian Art Nouveau. Although Hungarian architects also added very prestigious and valuable buildings to the route and Budapest in general during the late Habsburg era, the involvement of international stars rendered the character of the Nagykörút truly worthy of European metropolises. However, the demand for foreign experts – in particular the firms of Austrian architects – did not always win clear success in the domestic press and opinion, believing there to have been Hungarian experts who could have done the work.33

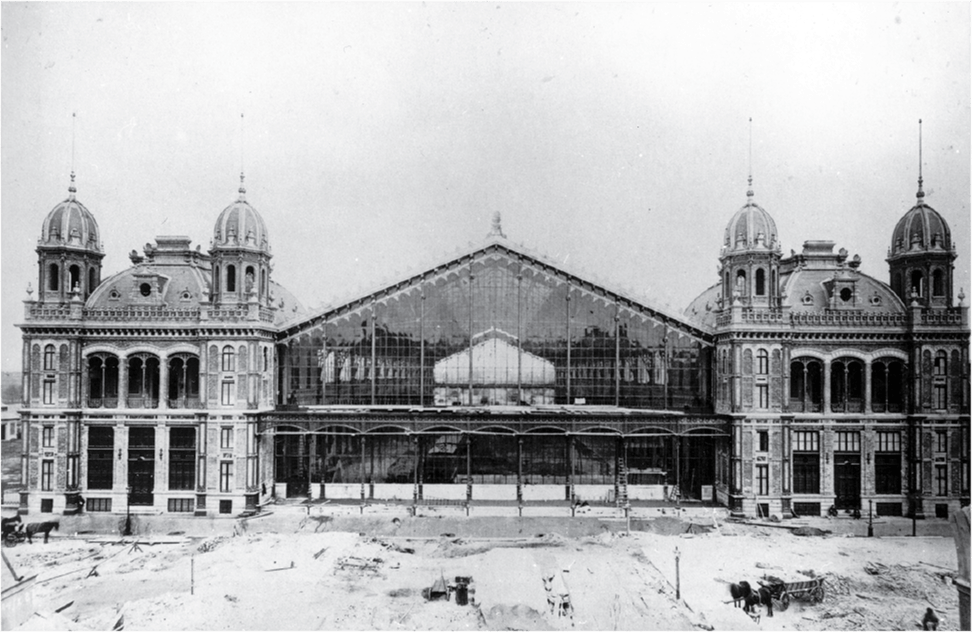

Of all the public buildings, the Nyugati Railway Station has the longest history. A railway station occupied this site since 1846, when the first Hungarian railway line opened between Pest and Vác.34 With the expansion of the railway network, the old station proved insufficient. The new, iron-and-glass station hall was built with the old building still standing underneath, a solution that cleverly allowed the rail traffic to run smoothly.35 It was the widest iron-framed square in Hungary at the time, at 42 meters. Thanks to the transparent structure, the sight of the trains was also allowed to become part of the streetscape of the boulevard.36

The building consists of a symmetrical arrangement of two brick volumes and a monumental iron-and-glass hall, which was a brilliantly original solution for the time. The brick sections, which house the waiting rooms, restaurants, post office, ticket offices, and other services, were built by the Austrian State Railways Company [Österreichische Staatseisenbahn-Gesellschaft], with Auguste Wieczffinski de Serres, Head of the Directorate for Construction as the lead designer. The design and construction of the hall structure was carried out by the Parisian Eiffel Company, under the engineer Theophil Seyrig (1843–1923).37

Overall, the railway station building has a strong French character.38 The arched mansard of the roof of the iron-framed brick wings, the small turrets, and the mansard windows at the corners, are associated with certain buildings of the French Renaissance, such as some of the pavilions of the Louvre. Also typical of French architecture are the segmental-arched façade openings. The wide iron-glass structure stands without intermediate vertical support. Its modernity, however, blends with the classical elements of historicism, as the ornately crafted columns and lacework iron brackets enhance the aesthetic of the engineering.

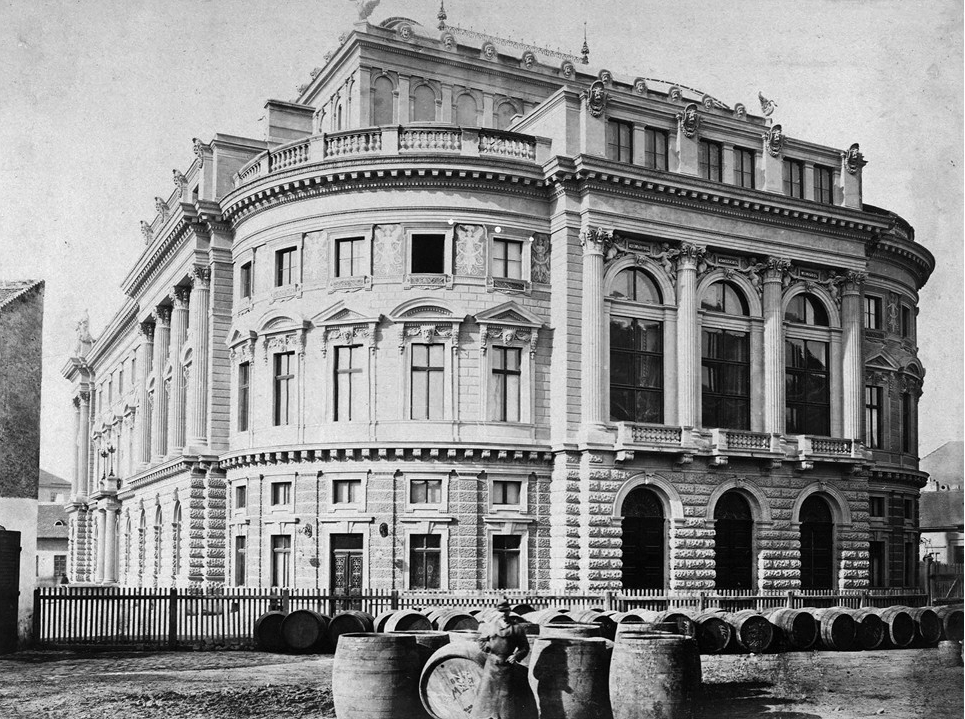

The historicist theaters of the Nagykörút were designed by the Viennese architecture office of Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer. The Népszínház was among the first public buildings of the Nagykörút, built between 1874 and 1875 when the first steps of the boulevard’s construction were taken. It operated as the National Theatre from 1908 to 1964, before being demolished in 1965 because of metro construction.39 This theatre was built in Neo-Renaissance style with a portico front at the façade opposite the Nagykörút. Originally, the building was designed for the site of Hermina tér on the Sugárút, but the Budapest Opera House by architect Miklós Ybl was built on that site. In turn, a plot on the boulevard was then designated for the building, which was reversed during a design modification, as earlier plans would have had the main façade facing the boulevard.40 The reason for the modification was that the building committee wanted the building to face the city center. As there still stood single-storey buildings of a village-like character on the opposite side of the theatre, the committee planned to create a square with a nice view and convenient access to the main entrance.41 The design already took into account the contours of the boulevard, with particular attention paid to the sophisticated design of the rear façade, which was architecturally as valuable as the main façade. Although the façades followed the traditional Neo-Renaissance with their angular shapes, classic columns, classic window frames, tympanum, and attic decorated with sgraffito work, the rounded corners of the rear façade foreshadow the Neo-Baroque style that Fellner and Helmer’s architecture soon revealed. The same tendency can be seen in the interiors, where classical forms were more prevalent than in Fellner and Helmer’s later theatres, though the strong gilding and decoration of the auditorium also foreshadowed the Neo-Baroque.

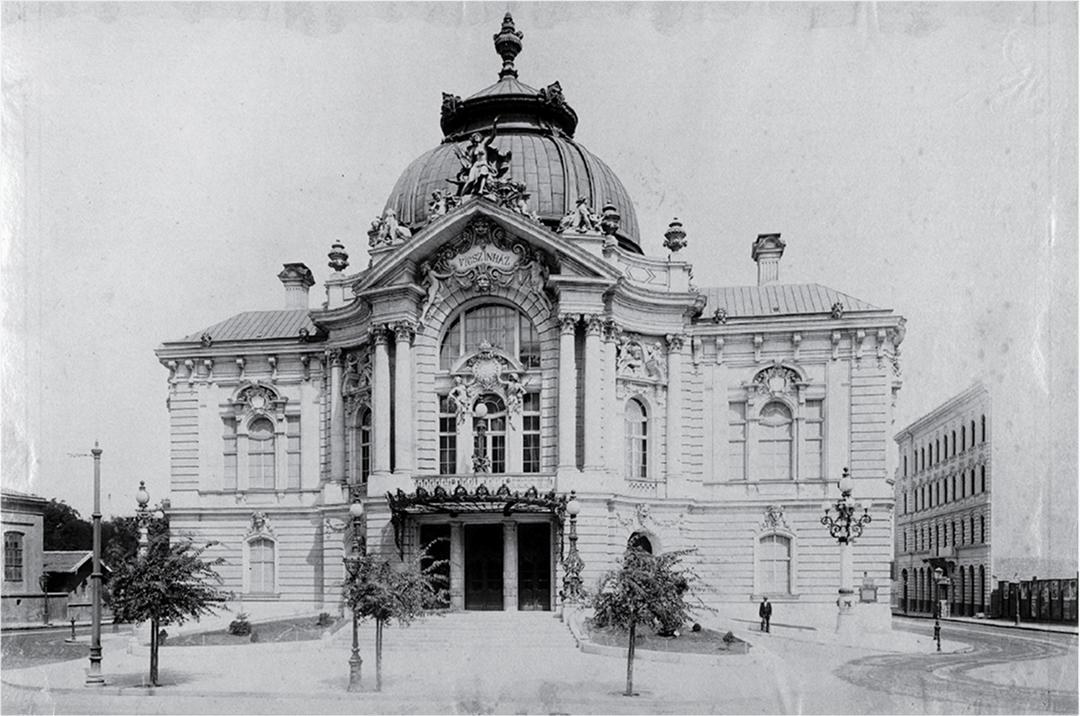

The subsequent theatre building designed for the Nagykörút, the Vígszínház was built in the golden age of the two architects’ Neo-Baroque period. The façade is characterized by a more dynamic design, with rounded and polygonal forms. Instead of the classic porticoed driveway, there is a wrought-iron-and-glass marquee, and the tympanum follows the curve of the façade’s protruding bay. In the case of this theatre, it was clear that it had to face the boulevard, as the city core lay in this direction. A small square was created in front of the building for the driveway, but it is much smaller than the one facing the Népszínház. The interiors and the auditorium have the same undulating shapes as the façade, though the inside is differs somewhat today, as the building was bombed during World War II and subsequent rebuilds did not fully follow the original design.

At the time when the Vígszínház was under construction, this section of the boulevard was still largely undeveloped and occupied by industrial buildings, for example, the steam mills of the Haggenmacher family and the Király Brewery. In fact, the site of the Vígszínház was initially the beer hall of the brewery.42 The construction of a public building of such prestige undoubtedly formed a major positive contribution to the development of the area, making it more attractive to investors and property owners. Just as the construction of the earlier presented Népszínház brought with it the improvement of its area, with the small buildings around it demolished to create a suitable space and making the location worthy of an elegant public building of cultural institution in the capital, the construction of the Vígszínház also gave a significant boost to the development of Lipót körút, at a later stage in the construction of the boulevard.

Historicist Residential Buildings on the Nagykörút

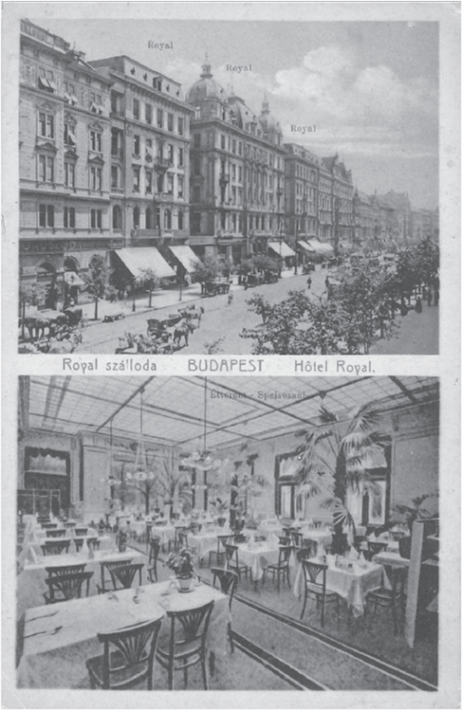

The above-mentioned public buildings are freestanding volumes and have an enclosed, separate building envelope. By contrast, the residential buildings on the boulevard are all built in a closed row, with the apartment block as the most common building type. Typically, these buildings are not purely residential, since shops, restaurants, cafés, and offices can be found on the ground floor, or sometimes even on the upper floors. There are also buildings designed for short-term residence, namely hotels, for example, the Rémy Hotel by the architect Ernő Schannen (József körút 4, 1894–1895), and the Royal Hotel by Rezső Lajos Ray (Erzsébet körút 42–49, 1895–1896). Both buildings are fine examples of Neo-Baroque architecture. The Rémy Hotel has a richly decorated façade, with giant pilasters and ornate window surrounds. The Royal Hotel is architecturally quite varied, with its mansard domed central pavilion and two side pavilions separated by a French courtyard.

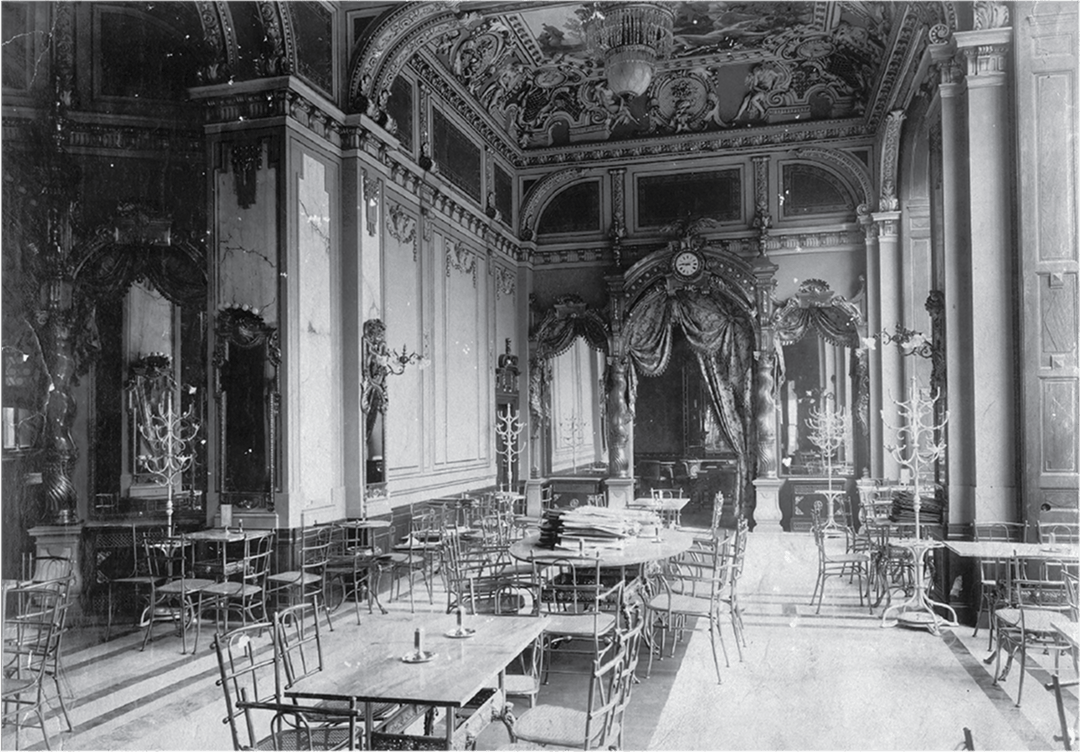

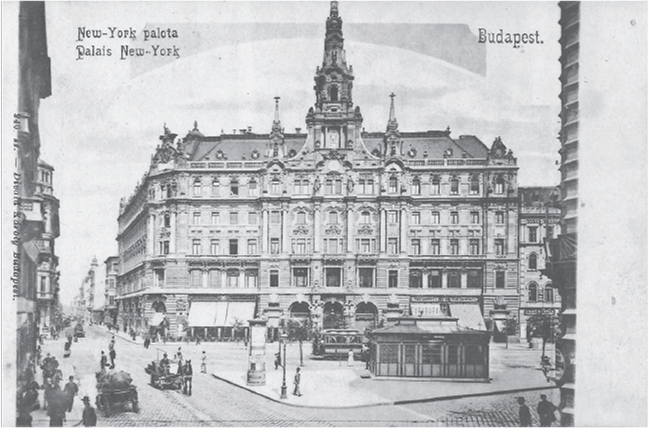

Among the commercial spaces located on the ground floor of apartment buildings, hospitality facilities, most notably cafés, should be highlighted. The historicist cafés – for example, the Café of the New York Palace by Alajos Hauszmann (9–11 Erzsébet körút, 1891–1894) –played a significant role in the community life of the boulevard and were architecturally remarkable interior designs of historicism. Major artists of the time worked on its decoration: ceiling paintings by Károly Lotz (1833–1904), Ferenc Eisenhut (1857–1903), and Gusztáv Magyar-Mannheimer (1859–1937), and sculptural ornaments by Károly Senyei (1854–1919). It is worth mentioning the ceiling fresco depicts features a miniature version of the Statue of Liberty in New York, along with allegorical figures.43

The New York Palais and the Café on its ground floor are notable examples of the Hungarian Neo-Baroque style. The building was designed for the New York Insurance Company by a much-employed, prominent architect of the epoch, Alajos Hauszmann (1847–1926), and his young colleagues Flóris Korb (1860–1930) and Kálmán Giergl (1863–1954). It has an exceptionally richly ornamented stone façade, highlighted by a tall complex tower in the center and two smaller towers. Not coincidentally, there are visible similarities with Korb and Giergl’s later work, the Klotild Palaces (1899–1902) in Ferenciek tere, which make use of a similar high tower and rich decor of stone ornaments. The New York Palace originally housed the offices of the insurance company and rental apartments but is now also an upscale hotel.

Close to the New York Café was another significant one: the EMKE (Transylvanian Hungarian Cultural Association [Erdélyi Magyar Közművelődési Egyesület]) Café on the corner of Erzsébet körút and Rákóczi út, which operated between 1893 and 1993 and was – similarly to the New York Café – a favorite place for artists.44 According to the Budapest Register of Addresses and Residences [Budapesti Czím- és Lakjegyzék], in 1898 the boulevard had several cafés, for example the Árpád (Erzsébet körút 8), Baross (József körút 45), Commerce (József körút 55), Edison (Teréz körút 24/a), Elevator (Ferenc körút 1), Franczia (Erzsébet körút 17), Hazám (József körút 3), Merán (Teréz körút 1/c), Nyugati (Lipót körút 34) and Vígszínház (Lipót körút 32).45 These have all disappeared, their interiors all lost.

Furthermore, it should be noted that it is impossible to describe all the residential buildings along the boulevard satisfactorily in the scope of this study. In addition, since some of the archival plans do not mention the name of the architect, but only that of the constructor, who may not have been involved in the construction of the building as a designer, it is complicated to establish the exact architectural history of certain buildings.

Turning to the buildings themselves, it is worth outlining the features that characterize their layout in general. The ground floor of the houses, all built around an open inner courtyard, is occupied by shops or restaurants, with rare exceptions, and the courtyard wings by apartments. The upstairs apartments can be accessed from an open corridor or loggia, with a maximum of one or two apartments per level from the main staircase. Following the tradition of urban architecture in the Habsburg era, servants had to use separate staircases. The majority of the apartment blocks accommodated a broader section of society, as they accommodated smaller apartments as well as large four- to five-room flats. Not every home had a private bathroom, but as time went on it became more and more common. An unfortunate feature of the open corridor-courtyard system is that the apartments on the lower floors tend to be darker, especially those with windows facing the courtyard. In some narrow courtyards, the trapped air became quite stagnant, and this was not beneficial for the health. As time has gone by, elevators have appeared on an increasing scale. They made the lighter upper flats more comfortable, through greater ease of access, but they are not yet widespread in the buildings on the boulevard.

The early construction phase of the Nagykörút saw the completion of Antal Szkalnitzky’s (1836–1878) four houses at the Oktogon (Andrássy út 48, 49, 50, 51), the octagonal square formed by the intersection of Teréz körút and Andrássy út. The four nearly identical houses are remarkable examples of splendid Neo-Renaissance urban mansions. Shaped to fit the octagonal square, that their main facade is the 11-axis corner side, where the central five axes form a protruding volume continuing to the fourth floor of the building. The side facades, which face the boulevard and Andrássy út, are similar. Employment of such a raised central volume, possibly with corner bays, is a form repeated in several of Szkalnitzky’s works, such as the Hungaria Grand Hotel (1868–1871) in the row of hotels facing the Danube, destroyed in the Second World War. Szkalnitzky was also the supervising architect for construction of the design by Friedrich August Stüler (1800–1865) for the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (1860–1865),46 hence this form is probably a recollection of that building, but also recurs in the architecture of other contemporaries, such as the Danish architect Theophil Hansen (1813–1891), professor of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and his students. Historically, the buildings of the Oktogon are more in keeping with Andrássy út, as they were built by the Avenue Construction Company [Sugárút Építő Vállalat], which was placed in charge of development of the new avenue.47

In the case of the buildings on Erzsébet körút, there exists a complete list of the architects who designed the houses and were the most frequently employed. As a result, we know that 49 houses existed on the boulevard by the time of the 1895 article in the Építő Ipar journal which published the list.48 An earlier building was still standing at number 31, on the site of which the Royal Orfeum was built in 1908, which then gave way to the present Madách Theatre in 1952–1953.49 There are 1 three-, 30 four-, and 18 five-storey buildings. The most employed architect was Zsigmond Quittner (1857–1918) with seven buildings, the second was Rezső Lajos Ray (1845–1899) with four, and the third was Győző Czigler with three. Quittner had recurring clients who commissioned him for repeated residential blocks on the boulevard. He designed two houses for Zsigmond Deutsch (Erzsébet körút 39, 1886–1888; Erzsébet körút 37, 1888),50 one for Sándor Deutsch (Erzsébet körút 7, 1886)51 and Zsigmond Reiner (Erzsébet körút 50, 1887), along with two for Károly Baumgarten (Erzsébet körút 44-46, 1898–1899;52 Erzsébet körút 41, 1890–1891)53 and for a member of the Hungarian Parliament, Lajos Csávolszky (Erzsébet körút 6, 1890–1891),54 the last now serving as the building of the 7th District Municipality. Most of his Nagykörút buildings are Neo-Renaissance, some with Northern Renaissance gables (7, 41, 44–46, 50) or angular bay windows (39, 44–46). Although the Northern Renaissance gable can also be seen in the Csávolszky House, the segmental-arched windows, the non-Classical window gable forms, and the rounded bay window can be considered as more Neo-Baroque.

Rezső Lajos Ray tended as an architect to favor the Neo-Baroque, and his works are therefore also associated with this style. The gently articulated façade of the house of József Gallitzenstein (Erzsébet körút 32, 1890),55 its slightly projecting first-floor bay windows, and its evocation of Palladian motifs are notably Neo-Baroque features. Ray also designed the previously presented three-pavilion building of the Royal Hotel.

In general, Győző Czigler’s architecture is characterized by an adherence to the Neo-Renaissance style, which can also be seen in his boulevard buildings, with a frequent use of brick façades given details in stucco and paintwork. The Korányi house (Erzsébet körút 56, 1885–1886),56 the first floor of which was the home of the famous professor of internal medicine Frigyes Korányi, and the house ordered by the widow of the confectioner Pál Kehrer (Erzsébet körút 4, 1887–1888)57 were built with unambiguously Renaissance brick façades. The ground and upper floors are separated from the other floors by a definite, plastered cornice, and the window framings are classic. Czigler’s most unique building on Erzsébet körút is the savings bank tenement house of the Pesti Hazai Első Takarékpénztár, at the corner of Rákóczi út. In this building, the offices and apartments of the savings bank were located along separate staircases. Although the side façades also have the typical Neo-Renaissance brickwork, the rounded corner with its giant columns and the crowning onion dome transform it into one of the most distinctive buildings on the boulevard. On the exterior and interior façades, some attributes refer to the financial institution’s function: beehives, bees, and the statue of Hermes by the sculptor Antal Szécsi (1856–1904) which formerly stood atop the dome, but was destroyed in the Second World War. On the other side of Rákóczi út, another key radial avenue, stands another corner building, the Zsigmond László House (József körút 2, 1897) with a mansard dome, designed by István Kiss (1857–1902). Together, the two buildings form an attractive feature at the intersection of the main routes.

In the 1950s, major changes were made to the buildings, especially on the ground floor, most often for several buildings around the Blaha Lujza tér, so the tenement palaces designed by Czigler, István Kiss, and the house of the EMKE café were partitioned off to create open arcades.

Returning to Győző Czigler’s work on the Nagykörút, it is worth mentioning the tenement house of Jenő Rákosi (József körút 5, 1889–1890, demolished), where the Neo-Renaissance brick façade was crowned with frieze paintings by Károly Lotz. The building was demolished, along with the rear wing (Rökk Szilárd utca 4, 1892–1893), which was the printing house of the daily newspaper Budapesti Hirlap, operated by Jenő Rákosi (1842–1929). Czigler’s building on Teréz körút, the tenement palace of the Károlyi Nemzetségi Alapítvány (Teréz körút 41, 1891–1892) has a red-brick façade whose frieze, rich in plastic decoration, is sheltered by a wide cornice. Czigler also designed Pál Luczenbacher’s apartment building (Teréz körút 49, 1886–1887) on the corner of Podmaniczky utca. On the corner of the large mansard dome of the house, putti bear aloft the heraldic crest of the Luczenbacher family.

Displaying family crests is a form of self-representation for the owner, along with monograms on balcony balustrades, door grilles, stucco ornaments, and other ornaments for representational purposes. It is typical that instead of signs and plaques with the name of the architect, it was the owner who wished to show the passers-by that he could afford to build a palace on the Nagykörút. More indirect self-representation was provided by towers, sculpted ornamentation, and ornate corner design. Even if the building did not have the most elegant apartments inside, the external appearance was very important: the exterior and the location of the building made the apartments more attractive, and, in some cases, even a smaller apartment was more expensive to rent than in other locations. For this reason, some of the buildings were mocked as “háziúr stílus”, in English landlord style.58 The towers with their variously shaped helmets and domes, or the ornate gables, defined not only the boulevard but the whole of Pest. However, in many cases, they were not restored to their original form after the Second World War.

In connection with the question of domes, steeples, and gables, it is worth mentioning the house of Henrik Schossberger (1885–1886) by the architect Henrik Schmahl.59 The apartment building, with its long rounded Northern Renaissance-inspired façade and three internal courtyards, has eight gables, two corners, and two main façade bay windows. The corner bay windows with a finial on their top mark the most elegant, four- to five-room apartments. Most of the other apartments have two or three rooms and they – except for the smallest apartments on the side streets – were equipped with en-suite bathrooms.

One Neo-Baroque example of ornate complex corner structures was the house designed by József Hubert (1846–1916) and Károly Móry (1845–1921) on the corner of Ferenc körút and Üllői út. (Üllői út 43, 1890, demolished).60 The giant columns with sculptural decoration, the complex, stretched corner cupola that surpasses the steeples of the Baroque church towers, and the rich decoration of the building made it divisive in the public eye. Architect Gusztáv Nendtvich (1854–1891) presented it in the journal Építő Ipar as the “unbridled fantasy” of otherwise talented architects who “had strayed into the impossible”.61 Irreparably damaged during the fighting against Soviet troops in 1956, it was finally decided to demolish it.

Besides Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque, there was also a tendency of historicism that drew on medieval styles. One of its masters was Samu Pecz, who also designed an apartment building for the Nagykörút. Another two houses were designed by him for the Wirnhardt family facing József körút. The first one (József körút 62, 1889–1892)62 was designed in Neogothic style, with a façade decorated with carved stone, and two triangular gables at the ends. Pointed-arched windows and Gothic-inspired carvings are the most distinctive elements. The style is also reflected in the interiors, with ribbed vaults in the staircase and pointed-arched windows on the courtyard’s brick façades. Yet Pecz’s architecture was not only influenced by the Middle Ages, as the second house (József körút 64, 1892),63 inspired by the Florentine Renaissance, shows.64

As previously noted, historicism drew on historical styles. In most cases, this means the transposition of architectural elements, gable forms, window framing types, and other design features into a new architectural task. However, there were other examples where the owner directly commissioned a copy of a specific building. Such is the case of Count Géza Batthyány’s palace (Teréz körút 13, 1884–1885) designed by Alajos Hauszmann.**key=65** Its model was the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, a work of Benedetto da Maiano, built 1489–1538. All the same, it is not a direct replica, since while the original building is situated at the corner and its main façade is nine axes wide, the Batthyány Palace has seven axes and is built in a closed row. The positioning of the entrance is also different, with the Florentine palace in the center and the Hungarian palace on the first axis on the left. Despite the dimensional shift and the subtle differences revealing a slight degree of contrast, the architect even copied the rings for tethering horses on the ground-floor façade. The ground floor and first floor of the palace were occupied by Batthyány’s elegant apartment, with a small apartment downstairs for the younger Batthyány. Interior walls and ceilings were decorated with sculpted and painted ornaments. The top floor was used for rental purposes.

Evaluation of the Historicist Architecture of the Nagykörút

Predominating on the Pest side of the Nagykörút was the stylistic trend of historicism, including Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, and the eclectic idiom created by their mixing. This trend was an international architectural tendency of the period, based on the evocation of historical styles. Most of the historic buildings are residential, but there are three significant public buildings too.

The Nyugati Railway Station can be regarded as belonging to the international canon, thanks to the work of the world-famous French company of Eiffel. The pioneering iron-framed hall building is a tribute to the technical achievements of the 19th century. Another internationally important but less widely known architectural office, Fellner and Helmer, designed the theatres known as the Vígszínház and Népszínház, later the National Theatre. This firm was a specialist in theatre architecture at the time, designing theatres to meet the needs of the time. Given the Austrian repression and the Hungarian national awakening, and the fact that other architects were not invited to tender, Fellner and Helmer’s work was not welcomed by the Hungarian architectural community. None of their works on the boulevard have survived in their original state, as the Népszínház was demolished in 1965, and the interior of the still-standing Vígszínház is still visible in a reconstructed form, with changes to the original structure and appearance.

The boulevard was the center of the capital’s commercial and tourist life, and an important place for artists, who enjoyed visiting its cafés, including New York and EMKE. The Grand Boulevard of Paris, with its similarly bustling life, was the model for this, while the Viennese boulevard, with the imperial-royal residence of the Hofburg, was more of an elegant, representative route. Hotels, like Rémy and Royal were built in an enclosed row, and many restaurants, cafés, and shops could be found on the ground floor of residential buildings. The boulevard was also an attractive residential area for Budapest’s citizens, who found it a matter of prestige to rent apartments in the palatial-looking tenements, let alone to buy land and build houses along the route. Decorative, although in comparison with the Andrássy út somewhat less elegant buildings were erected here. Instead of stone facades, brick or painted stucco facades are typical. Smaller and larger apartments occupy each floor of the buildings. However, there are also buildings, like the Korányi house and the Batthyány Palace, where the first floor was occupied by a large apartment used by the owner. This division has disappeared nowadays, as the apartments in the buildings have long been divided into smaller units.

The aesthetically innovative architectural movements of the turn of the last century also made appearances along the route, but the most internationally prominent of these was Viennese Secessionism. Such apartment buildings mostly arose along the most recent part of the road, Szent István körút.

Although the buildings have undergone significant changes – the ground floor was arcaded in some places, after the Second World War and the Revolution of 1956 several gables and corner domes were removed, or several buildings entirely destroyed – the overall picture shows the dominance of historicism even today.

Besides the buildings presented in the study, others could have been mentioned, as the boulevard has a notably rich historicist heritage. Even if not all buildings are of outstanding architectural importance, the overall visual effect of the boulevard is, at the same time, an important architectural legacy that must be preserved for posterity.

EDVI-ILLÉS, Aladár. 1896. Budapest műszaki útmutatója. Budapest: Pátria.

PREISICH, Gábor. 1960. Budapest városépítésének története I. Buda visszavételétől a kiegyezésig. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó.

PREISICH, Gábor. 1969. Budapest városépítésének története III. A két világháború közt és a felszabadulás után. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó; PREISICH, Gábor. 1998. Budapest városépítésének története 1945–1990. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó.

PREISICH, Gábor. 1964. Budapest városépítésének története II. A Kiegyezéstől a Tanácsköztársaságig. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó, pp. 25–82.

PREISICH, Gábor. 2004. Budapest városépítésének története Buda visszavételétől a II. világháború végéig. Budapest: Terc.

HANÁK, Péter. 1984. Polgárosodás és urbanizáció. Történelmi Szemle, 27(1–2) pp. 123–144.

VADAS, Ferenc. 2005a. Városrendezés Budapesten a 19. században. In: Csendes P. and Sipos A. (eds.). Bécs – Budapest. Műszaki haladás és városfejlődés a 19. században. Vienna, Budapest: Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna and Budapest City Archives, pp. 21–34.

TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2020. Little Vienna – Little Budapest: Ring Boulevards of Three Midsized Towns in the Habsburg Empire, 1848–1920. In: Thomas, A. et al. (eds.). Yearbook of Transnational History 3. Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, pp. 33–54.

EKLER, Dezső and TAMÁSKA, Máté. 2016. Ringstraßen im Vergleich.: Varianten auf eine städtebauliche Idee in Wien, Budapest und Szeged. In: Hárs, E., Kókai, K. and Orosz, M. (eds.). Ringstraßen: Kulturwissenschaftliche Annäherungen an die Stadtarchitektur von Wien, Budapest und Szeged. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, pp. 25–62.

N. KÓSA, Judit. 2022. Nagykörút – Történelmi séta Pest főutcáján. Budapest: Városháza Kiadó.

RUISZ, Rezső. 1960. Nagykörút. Budapest: Képzőművészeti Alap Kiadóvállalata.

KUBINSZKY, Mihály. 1983. Régi magyar vasútállomások. Budapest: Corvina Kiadó.

KÖRNER, Zsuzsa. 2010. Városias beépítési formák bérház és lakástípusok. Budapest: TERC.

LAMPEL, Éva and LAMPEL, Miklós. 1998. Pesti bérházsors. Budapest: Argumentum.

Vadas, F., 2005a, p. 22.

Vadas, F., 2005a, p. 23.

GYENGŐ, László. 1981. A Rigler, Seidl és Zitterbarth család genealógiája. Levéltári Szemle, 31(1), p. 167.

VADAS, Ferenc. 2005b. Budapest vasúti hálózata és pályaudvarai. In: Csendes P. and Sipos A. (eds.). Bécs – Budapest. Műszaki haladás és városfejlődés a 19. században. Vienna, Budapest: Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna and Budapest City Archives, pp. 143–144.

TÓTH, Mihály. 1966. Hajózó csatorna Budapesten – egy terv a múlt századból. Közlekedéstudományi Szemle, 16(1), pp. 40–42.

Vadas, F., 2005a, pp. 27–28.

More about the Hungária körgyűrű: BERCZIK, András, HUPFER, Rezső and NAGY, Ervin. 1967. A Budapesti Hungária körút múltja és jövője. Városépítés, 3(1), pp. 14–19.

DEZALLIER D’ARGENVILLE, Antoine-Nicolas. 1787. Vies des Fameux Architectres Depuis la renaissance des Arts avec la déscription de leurs ouvrages. Paris: Debure, p. 1.

For example: LETAROUILLY, Paul. 1840. Édifices de Rome moderne 3. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères; LÜBKE, Wilhelm. 1855. Geschichte der Architectur von den ältesten Zeiten bis zur Gegenwart. Leipzig: Graul; GAILHABAUD, Jules. 1852. Denkmäler der Baukunst. Hamburg: Ludwig Lohde.

SISA, József. 2009. A neoreneszánsz Európában és Magyarországon – Vázlatos áttekintés. In: Csáki T., Hidvégi V. and Ritoók P. (eds.). Budapest neoreneszánsz építészete. Budapest Főváros Levéltára, 2018. Budapest: Budapest City Archives, p. 11.

21 Schottenring. It was previously considered to be the first Neo-Baroque building in Vienna. Although the claim has been disproved, further research suggests that it was one of the first ones. More about it: TÓTH, Enikő. 2019. Neobarock und Luxusgefühl. Das Palais Sturany in Wien. Steine Sprechen, 58(154), pp. 42–51.

ROZSNYAI, József. 2018. Meinig Arthur. Budapest: Holnap Kiadó, pp. 19–21.

ROZSNYAI, József. 2011. Neobarokk építészet Magyarországon az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia idején, különös tekintettel Meinig Arthur építész munkásságára. PhD thesis. Faculty of Humanities, Eötvös Loránd University, pp. 7–8.

Rozsnyai, J., 2011, pp. 53–57.

KELECSÉNYI, Kristóf. 2020. Schmahl Henrik. Budapest: Holnap Kiadó, pp. 127–152.

SISA, József. 2014. Lechner az alkotó géniusz. Budapest: Iparművészeti Múzeum, MTA BTK Művészettörténeti Intézet, p. 28.

Land register file, parcel no. 37553, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.37.c.9297 – 37553. Budapest City Archives.

More about Fellner and Helmer’s theatres: HOFFMANN, Hans Christoph. 1966. Die Theaterbauten von Fellner und Helmer. Munich: Prestel-Verlag.

A Magyar Mérnök- és Építész-Egylet Heti Értesítője. 1893. A budapesti Vígszínház-egylet. A Magyar Mérnökés Építész-Egylet Heti Értesítője, 12(1–40), p. 206.

Vadas, F., 2005b, p. 143.

VADAS, Ferenc. 1998. Az első nagyvárosi pályaudvar: a Nyugati. In: Gyáni, G. (ed.). Az egyesített főváros. Pest,

Buda, Óbuda. Budapest: Budapest Főváros Önkormányzata Főpolgármesteri Hivatala, pp. 304–308.

Vadas, F., 2005b, p. 148.

BURJÁN Balázs. 2017. A Nyugati pályaudvar építő- és díszítőkövei. Építés – Építészettudomány 46(1–2), pp. 59–60. doi: 10.1556/096.2017.010

Vadas, F., 2005b, p. 149.

Budapest Főváros Tanácsa Végrehajtó Bizottsága üléseinek jegyzőkönyvei. Records of the meetings of the Executive Committee of the Budapest City Council, 6 January 1965, inv. no. HUBFL.XXIII.102.a.1. Budapest City Archives.

Fellner, Ferdinand: Projekt fur das Volks-Theater in pest: Project-Skizze. Wien, 1872. Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár, Budapest Gyűjtemény. Inv. Nr.: AN061749. Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library.

Magyarország és a Nagyvilág. 1875. A budapesti Népszínházról. Magyarország és a Nagyvilág, 11(43), p. 539.

ARCANUM. 2020. Budapest topográfiai térképsorozata, 1882, 1895 [online]. Available at: maps.arcanum.com/hu/browse/city/budapest/ (Accessed: 26 June 2024).

KONRÁDYNÉ GÁLOS, Magda. 1981. New York kávéház. In: Tóth, E. (ed.). Budapest Enciklopédia. Budapest: Corvina Kiadó, pp. 263–266.

MUSKÁT, Péter. 2015. EMKE kávéház [online]. Available at: https://emkekavehaz.hu/ (Accessed: 16 July 2024).

Anonym. 1898. Kávésok és kávéházak. In: Budapesti Czim- és Lakjegyzék 10. Budapest: Franklin-Társulat, pp. 559–561.

SISA, József. 2022. Szkalnitzky Antal. Budapest: Holnap Kiadó pp. 44–45.

Sisa, J., 2022, pp. 131–134.

Építő Ipar. 1895. A budapesti körút építéséről. Az Erzsébet-körúti házak statisztikája. Építő Ipar, 19(6), pp. 61–62.

SÓS, Eszter. 2003. Egy legendás orfeum. A Madách Színház épületének története – I. rész. Zsöllye, 4(7), p. 23.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 33911, 1888, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 33911. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 33668, 1886, inv. no. HU.BFL. XV.17.d.329 – 33668. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 34059, 1889, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 34059. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 34057, 1887, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 34057. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 34563, 1890, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 34563. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 34359, 1890, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 34359. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 34064, 1884, HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 34064. Budapest City Archives.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 34564, 1887, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 34564. Budapest City Archives.

Építészeti Szemle. 1895. A Légrády-féle épület. Építészeti Szemle, 4(4), p. 101.

Building authorisation plan documentation, parcel no. 29438–29440, 1886, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.17.d.329 – 29438–29440. Budapest City Archives.

Land register file, parcel no. 36876, 1852–1927, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.37.c. 9335 – 36876. Budapest City Archives.

“Vagy »last but not least« fölhívom kartársaim közül azokat, a kik még nem látták volna, hogy ne sajnálják a fáradságot, hanem menjenek el s nézzék meg az Üllői-út és a Ferenc-körút sarkán a kaszárnyával szemben levő házat. Érdemes megnézni, sőt érdemes arra is, hogy emlékezetünkbe véssük, mert igazán a netovábbját élvezhetjük annak, hogy micsoda lehetetlenségekbe tévedhet még egy különben igen tehetséges művész fantáziája is, elveszti minden irányát, ha féktelenné válik és ha csak azt az egy célt látja maga előtt, hogy – az ő nézete szerint – újat és originalisat alkosson.” NENDTVICH, Gusztáv. 1891. Budapest építőművészete. Építő Ipar, 15(3), pp. 17–18.

Land register file, parcel no. 35639, 1866–1922, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.37.c. 6911 – 35639. Budapest City Archives.

Land register file, parcel no. 35640, 1866–1928, inv. no. HU.BFL.XV.37.c. 6912 – 35640. Budapest City Archives.

- BALOGH, Ágnes and RÓKA, Enikő. 2022. Pecz Samu. Budapest: Holnap Kiadó, 2023. 180–181.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31577/archandurb.2023.57.3-4.1

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License